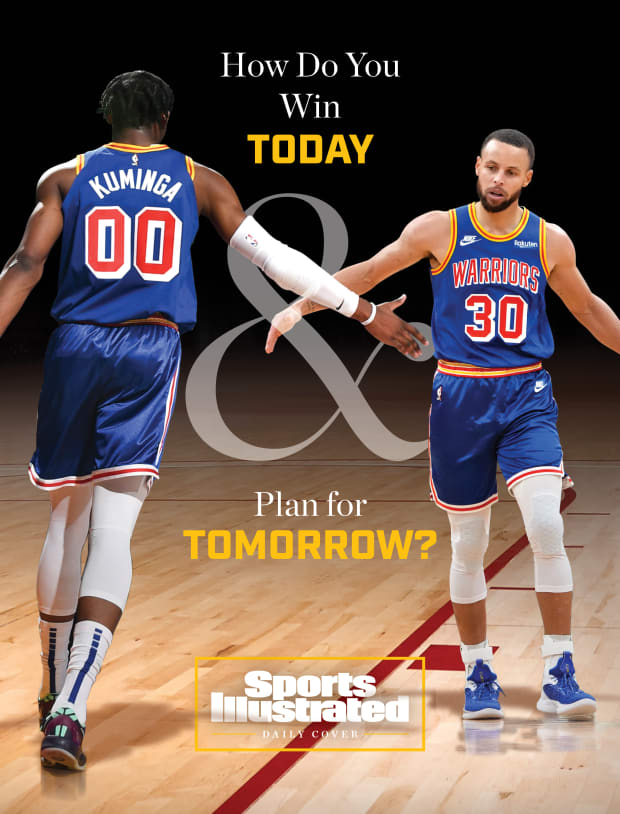

Inside Golden State’s plan to chase more championships now while grooming their stars of the future.

To glimpse the Warriors’ present and future all at once, consider two options: You could borrow Doc Brown’s DeLorean, steal some plutonium and take a joy ride to 2025; or you could, through a different sort of magic, tap two video streams, each fixed on a different era.

One stream would feature Stephen Curry, avatar of the current Golden State dynasty, chasing Ray Allen’s three-point record while obliterating the Trail Blazers. The other would show Jonathan Kuminga and Moses Moody, the Warriors’ stars of tomorrow, combining for 62 points in a victory over the Clippers.

You could view it all simultaneously—without any need for a flux capacitor.

Indeed, it all happened on Dec. 8, with Curry collecting six threes in a nationally televised victory over Portland, while Kuminga and Moody simultaneously showed out for the Warriors of Santa Cruz, the franchise’s G League affiliate. All you needed to see the present and future collide was an extra screen and good Wi-Fi.

What Golden State’s brain trust is now attempting is far trickier: Chasing more championships in the present—behind dynasty veterans Curry (33), Klay Thompson (31) and Draymond Green (31)—while simultaneously grooming the Warriors’ stars of tomorrow: Kuminga (19), Moody (19) and James Wiseman (20).

Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin; Noah Graham/NBAE/Getty Images (Kuminga); Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE/Getty Images (Curry); John W. McDonough (Court)

In the NBA universe, this is bordering on science fiction, an attempt to bend the laws of physics and distort the space-time continuum. Contend now AND build for the future? At the same time?! Madness!

“It is unique, and it is uniquely challenging,” says former Celtics president Danny Ainge, whose team won the 2008 championship and stayed in contention for another few years. “It’s something that everybody would love to do, theoretically.”

Ainge eventually cashed out his aging stars to acquire the picks that launched an eventual rebuild. But what the Warriors are attempting, straddling eras and generations, is altogether different.

It hasn’t been done in the modern era—not successfully, anyway. And it’s easy to understand why. In the NBA, perennial contenders generally draft low or trade their picks for win-now vets. They rarely have high-talent youth to develop, if they have any youth at all. Every resource is poured into this season, this roster, this playoff run. There’s no time to plan for the future—especially now, in this era of rampant superstar movement.

So NBA dynasties generally crash and burn, undone by age and injuries. Think of the 1980s Lakers, after Magic’s retirement. Or the Celtics, once Larry Bird faded. Or the Bulls, post-Jordan. Or the Lakers again, once Kobe Bryant declined. It can take years, even decades, to build another contender.

But this Warriors dynasty, which won three titles and made the Finals every year from 2015 to ’19, is traveling a different reality. Fate threw a grenade in their timeline in ’19, opening a strange new path. The twin losses of Kevin Durant (to free agency) and Thompson (to ACL surgery), followed by a hand injury to Curry, plunged Golden State to the bottom of the standings, which earned them the No. 2 pick in the ’20 draft, which became Wiseman, a supremely athletic 7-footer. A second injury to Thompson (a ruptured Achilles) buckled the Warriors again last season, resulting in another lottery pick, this time 14th. They chose Moody, a deft three-and-D wing. Along the way, the Warriors made an opportunistic trade with the Timberwolves that netted them the seventh pick in the ’21 draft, which they used to draft Kuminga, a brawny and athletic forward.

Noah Graham/NBAE/Getty Images

All are talented enough, and young enough, to plausibly become the Warriors’ new core after their current stars age out. Perhaps not as transcendent or as dominant but strong enough to carry the franchise into the post-Curry era.

“They’re all amazing talents,” Curry enthuses. “They’re all pretty versatile.”

He singles out Moody for his shooting and defense, praises Kuminga as “a freak athlete” with a “good feel for the game” and calls Wiseman “the perfect guy that can literally do everything on the court.” Says Curry: “They have a lot in the bag.”

Oh, and meanwhile, Curry himself is still playing like an MVP—and has the current Warriors on track for another run to the Finals. Maybe several. Which means this franchise is now running on parallel tracks: one aimed at June, the other at some distant point on the horizon. One focused on championships. One focused on development.

If it all goes well, Golden State could gracefully segue into the next era, without all the crashing and burning and prayers to lottery gods. Except it’s never been done. So when the man charged with navigating this strange new path is asked about a road map to follow, he can only chuckle.

“I don’t know that there is a map,” says Warriors general manager Bob Myers. And when asked about the odds of pulling this off, that chuckle becomes a lengthier laugh. “I’ll tell you in a couple years,” he says.

Indeed, the Warriors are making it up as they go, but they do have a plan of sorts. It involves frequent use of the G League, where the prospects get critical game reps; extensive film study and scrimmaging on off days; a revamped coaching staff filled with development specialists; NBA minutes whenever coach Steve Kerr can spare them; and, most critically, daily lessons from the basketball legends who happen to occupy the locker stalls between them.

If there’s a road map connecting the Warriors’ glorious present to a vibrant future, it’ll be drawn by the same guys who got them here in the first place.

Every so often, Wiseman’s phone will buzz with the ghosts of Big Men Past: Hakeem Olajuwon, Arvydas Sabonis, Chris Webber, Rik Smits, Vlade Divac. They arrive in grainy YouTube clips, via text messages from Andre Iguodala.

The 37-year-old Iguodala, a key member of the Warriors’ three title runs and MVP of the 2015 Finals, returned to the club this season after two years away. If his athleticism has perhaps waned a bit, his wisdom and influence have not. Every text carries a pointed lesson.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Olajuwon’s footwork was legendary. Sabonis and Divac were among the best-passing centers of all time. Webber was brilliant as both a playmaker and scorer, inside and out. Smits had a killer right-hook shot.

“You’re not just soaking up the game right now, but you’re soaking up the history of the game,” Iguodala says of his tutelage of Wiseman. “And that’s a part of being a master at your craft. You got to know the history of it, and you have to have a respect for every era.”

For Wiseman—who played just three college games before turning pro and is still recovering from a knee injury that cut short his rookie year—the off-court study is just as critical as the on-court work. He arrived in the NBA with immense physical gifts: speed and agility, power and finesse, a respectable jump shot and a 7' 6" wingspan. The key now is learning to channel it all, which is why Iguodala keeps sending history lessons.

“Making sure that I expand my game,” Wiseman says. “You know, being 20 years old, I still got a lot to learn. But just like the little details is what matters.”

A meniscus tear has kept Wiseman out since April. But his rehab has provided an unexpected perk—daily workouts with Thompson, who is also on the rehab trail, and whose work ethic is legendary. Every session is laced with Klay mini sermons: Embrace everything, both good and bad. Never get too high or too low. Always stay copacetic.

“Really, just make sure that every rep is game-like,” Wiseman says of following Thompson’s example. “Every rep you do, go as hard as you can, because when you get in the game, it’s gonna be easier. So, creating a great habit, never creating bad habits when you work out.”

From Curry, Wiseman gets sermons on consistency, the ability to perform at the same high-level night in and night out, through an 82-game regular season and all the playoff games that follow.

“He told me, ‘Make sure you embrace the monotony of everyday life, in terms of the NBA,’” Wiseman says. “Every day, you have to embrace the fact you got to wake up every morning and do the same routine: shoot around, play the game, same thing over and over. Even in the offseason, you got to work out every day. … That is what makes a difference.”

Once Wiseman is game-ready—team officials are hoping for a January return—his first reps of the season might come in the G League, which the Warriors have enthusiastically deployed as a development tool.

Jed Jacobsohn/NBAE/Getty Images

Last season, the Warriors assigned Jordan Poole—then a struggling second-year guard—to the Santa Cruz Warriors for an 11-game stretch. He returned a more polished and confident player and is now a fixture of the Warriors offense, averaging nearly 18 points a game as Thompson’s stand-in.

Already this season, Kuminga has logged six games with Santa Cruz, and Moody five. There, the two teens get all the minutes, shots and responsibility they need to grow—opportunities that Kerr can’t afford to give them with this veteran-laden, title-chasing Warriors team.

The Santa Cruz squad runs the same system. And when the rookies are there, Myers and Kerr usually are, too, observing and providing feedback. The one-to-one G League farm system is still a relatively new innovation—and a luxury that dynasties of the past didn’t have. It’s become almost commonplace for young prospects, even lottery picks, to get their reps there.

“The G League’s emergence has really helped in that regard,” Kerr says. “There’s a bunch of guys in this league, who are now really good players who spent a lot of time in the G League. And we remind our players of that, too. There’s no shame. It’s a legitimate part of development.”

And while G League dominance does not always translate to NBA success, it can provide useful snapshots. The rangy Moody erupted for 37 points, 10 rebounds, five steals and two blocks—while shooting 5-for-11 from the arc—in that Dec. 8 victory over the Agua Caliente Clippers. That same night, Kuminga dropped 25 points—mostly on layups—his third straight game with 20-plus.

“It’s just a trial run with less eyes, less people sitting there watching you,” Moody says. “It’s more free, and you get to play loosely and figure things out.”

Meanwhile, the big league Warriors—after years of a veteran-heavy locker room—have retooled their staffing and routines to cater to their new youth contingent. New assistant coaches this season include former Nets head coach Kenny Atkinson, who built an outstanding reputation for player development with Brooklyn and Atlanta; Jama Mahlalela, former head coach of the Raptors’ G League team; and Dejan Milojević, whose résumé includes an eight-year run as head coach of Mega Basket in Serbia, where he mentored a young Nikola Jokić.

Kerr said the staff turnover was mostly about needing “new blood and fresh ideas,” but admits it’s no coincidence the new hires all have strong backgrounds in player development. Both the Nets and Raptors are renowned for it. And Milojević’s work with Jokić makes him a natural fit with Wiseman. “Putting him with James was a priority,” Kerr says.

“We have here a picture of what Wiseman can be,” Milojević says. “There is a process to achieve that. It’s not like in two months or three months or a year. It’s step by step.

“Step by step.”

The last time a vaunted dynasty tried to extend its run, it ended in bitterness and controversy, and an infamous veto.

Ten years ago this month, the Lakers agreed to a three-team trade that would have paired Chris Paul—then 26 and in his prime—with the 33-year-old Kobe Bryant while shipping out aging stars Pau Gasol (to Houston) and Lamar Odom (to New Orleans). That core made three straight Finals—and won championships in 2009 and ’10—before disintegrating in the ’11 playoffs.

Acquiring Paul would have given Bryant a fresh-legged costar and given the Lakers a new icon to carry the franchise once Bryant retired, a bridge to the next era. Alas, infamously, the deal was vetoed by then commissioner David Stern, acting in his role as steward of the New Orleans franchise, which was then jointly owned by the other 29 teams.

Paul was instead traded to the Clippers, for a younger package of players. And the Lakers never recovered, making two more playoff appearances with Bryant before falling into a six-year malaise.

So it goes for long-term contenders. When LeBron James ditched the Heat for the Cavaliers in 2014—after four straight Finals and two titles—he left behind an aging Miami roster. Four years later, James decamped to the Lakers, leaving behind a mostly barren Cleveland roster. The Cavs’ front office had (justifiably) spent those years making win-now moves, trading young players and draft picks in deals that brought them key players like Kevin Love, J.R. Smith, Iman Shumpert, Timofey Mozgov, Channing Frye and Kyle Korver.

In the NBA, perennially great teams spend a lot, draft low, get old and eventually run out of steam. The only modern dynasty to sort of defy that axiom is the Spurs, who collected five banners between 1999 and 2014, all with Tim Duncan as the centerpiece but with an evolving cast of costars: from David Robinson in the early years to Tony Parker and Manu Ginóbili and finally Kawhi Leonard.

Parker and Ginóbili were the rare low picks who blossomed into All-Stars. Leonard, taken 15th in 2011, was acquired in a shrewd draft-day trade. So San Antonio did manage to contend and build simultaneously, albeit with players who arrived with a little more polish—as young veterans of the European leagues (Parker and Ginóbili) or two years of college (Leonard).

But the Warriors’ situation has no modern precedent—a dynasty adding three lottery picks, while its three All-Stars are all still in their prime.

“We didn’t plan to have Klay go down for two years, or Steph to miss most of the year two years ago,” Myers says, “but it happened.”

Noah Graham/NBAE/Getty Images

Nor was it a given that Wiseman, Kuminga and Moody would even land here, or stick. The Warriors, as any team in their position would, explored moving their picks for immediate help (preferably another All-Star) over the last year. But nothing ever materialized.

So Kerr and his staff adapted, strategizing for the here and now and the sometime later.

“I can say this with sincerity: I want the Warriors to be great for the next 15 years,” Kerr says. “And I’m not going to be the coach here for the next 15 years. … So if that means that we grow the next core right now, over the next two years with this team, and they end up taking over the team, and the team is great for the next 10 years? That’d be awesome. I would love that.”

Of course, the immediate, obvious goal remains: Do everything possible to extend the championship window while Curry is in his prime. And Curry, who signed a $215 million extension in August, says he is comfortable with the moves the Warriors have made—and not made.

“If the goal is not winning a championship, then I don't want to be here,” Curry says. “But if you’re like, ‘What are our options? What makes sense? What’s realistic?’ I’m also a rational person. I understand the league works a certain way. You can’t just wave a wand and things are gonna go your way. That can’t be the expectation. But if you’re asking now and what we have, there’s a great opportunity to develop and maintain this core of what we’ve done, and just give it a shot. And then you can kind of ride that wave until the signs say to do something different.”

Warriors majority owner Joe Lacob, for one, sounds absolutely determined to pull off the rare feat of contending while cultivating the next generation. He’s referred to the recent draftees as a “bridge to the future.”

“[Fans] will hate me long-term if we go and do something that’s dumb,” Lacob said in a recent interview with Bonta Hill and Joe Shasky on 95.7 The Game, the Warriors’ flagship station. “We can’t go off a cliff. We have to sort of balance things and figure out how can we be as good as we can possibly be now, and be good in the future.”

Which means that, pending some unforeseen, blockbuster deal they can’t refuse, Wiseman, Kuminga and Moody are here to stay. All the Warriors have to do now is mold them into, well, Warriors.

The area just outside Golden State’s home locker room is called the Huddle Room, and its visual centerpiece is an artwork called the Oakland Tree, a sprawling twist of branches—all pebbled orange leather, like a basketball—each inscribed with a key phrase or moment.

“Strength in numbers”—the mantra of the 2014–15 team that won the first championship of this era. “We believe”—the slogan of the fierce ’06–’07 squad that upset the top-ranked Mavericks in the playoffs. “Be coachable.” “Do extra.” “Positivity is a choice.”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

To walk these halls is to be completely immersed in Warriors lore and Warriors values, and that quickly becomes evident when you hear the youngsters speak. They don’t sound like overeager kids, antsy to get their turn, their shots, their stats. They exude patience, perspective, balance—and an acute appreciation for the chance to play alongside champions, and compete for one.

“I feel like Simba in The Lion King,” Moody says. “Just the tradition. This team and this system is very rich, because they’re constantly pouring into us and grooming us almost for the crown.”

Even if that means a lot of DNP-CDs. Among members of the 2021 draft class, Kuminga ranks 25th in NBA minutes played, while Moody ranks 28th. So far, Kuminga has made 21 appearances with the Warriors, averaging 8.4 minutes and 4.3 points. Moody is averaging 6.3 minutes—and says it’s fine, instead relishing the chance to go shot for shot with Thompson in impromptu competitions on the practice court.

“My dad always says, ‘A smooth sea has never made a skillful sailor,’” Moody says. “So I’m looking for the bumpy route.”

Even once he’s healthy, Wiseman won’t get the starring role that Anthony Edwards has in Minnesota, or LaMelo Ball has in Charlotte, or the minutes that most high picks get when they land, typically, on losing teams.

“One thing I noticed coming in as a rookie is that you can never worry about your other peers,” Wiseman says. “Always worry about where you at, be in competition with yourself. And I’ll make sure I pass that down to Kuminga and to Moody, as well.” The lesson? “Indulge it, embrace it and just accept the fact that it’s going to be tough, but it’s gonna pay off at the end. It always does.”

Those messages are underscored almost daily by veterans like Thompson, who says, emphatically: “Banners are timeless. Records are meant to be broken. Individual statistics are meant to be topped. But banners hang forever. I try to tell these young guys that no one cares what your stats are by the end of season. The goal of the game is to win the game.”

There’s a tradeoff at work for the Warriors’ youngsters: a sacrifice in minutes and gaudy stats in exchange for the collective wisdom of Steph and Klay, Green and Iguodala. (And, of course, the chance to contend for titles, instead of losing 50 games.)

“Great trade-off,” Wiseman says. “I'm just honored to be able to play with Golden State, play with the greatest shooter of all time, play with Klay.”

Things change fast in this league, of course. A trade or another injury could scuttle everything the Warriors are planning for. But you can see a vague outline of a potential post-Curry future, featuring Wiseman, Kuminga and Moody, plus Poole (22) and Andrew Wiggins (26), a once-wayward former No. 1 pick who has blossomed under the Warriors’ banner.

“We’re a championship team,” Thompson says. “So when they do step in and take our minutes, we expect them to have the same success we did, as far as just being a contender year in and year out.”

Lacob once mused that the Warriors were “light-years ahead” of other NBA franchises, a remark that was widely mocked as arrogant. Now his team is again trying to outwit and outmaneuver the league, by planting the seeds of another championship core before the first one has even finished. But the Warriors don’t need to be light-years ahead—just a few 12-month cycles on the Gregorian calendar.

If their vision is accurate, their development plan sound and their teenagers as talented as they appear, the Warriors might be irritating their rivals well into the 2030s and adding another few branches on the Oakland Tree.

“We can be one of the greatest dynasties—and it’s not over,” Thompson says. “I truly believe that.”

• ‘He’s Made The Difference’: LaMelo Ball Has Charlotte Buzzing Again

• Scoot Henderson Is A Top Prospect In The G League. And He’s The Future.

• Life On The Fringes Of Division I Men's Basketball