... And what those players hear (or don’t hear) will alter the NCAA landscape.

When IMG Academy football coach Bobby Acosta wanted advice for how to talk with his players about systemic racism and the Black Lives Matter movement after the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, the first call he made was to a 16-year-old.

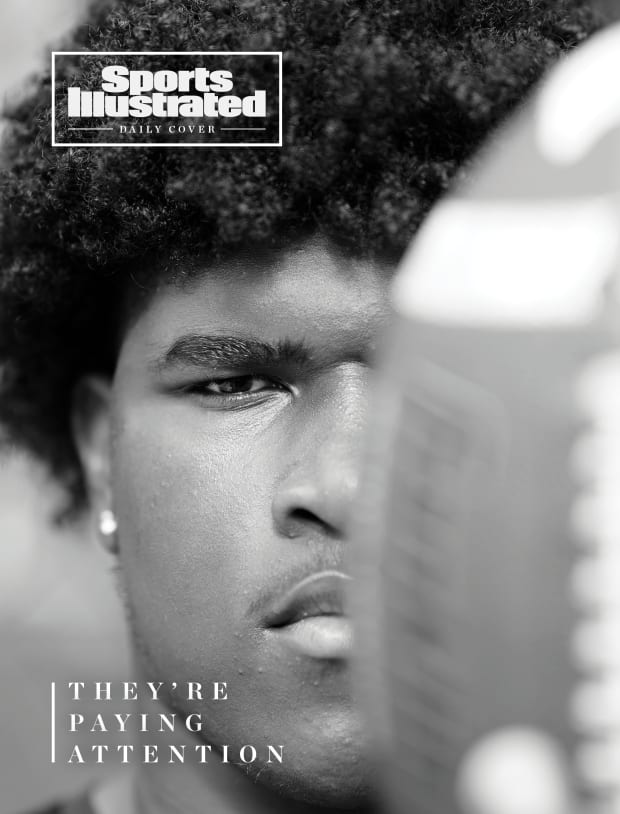

Tyler Booker is the nation’s top offensive lineman in his class—the “heartbeat” of the IMG team, says Acosta—and when the coach called, Booker told Acosta exactly where to start: Talk about it. Be honest about what’s happening. Don’t ignore this, even if it’s uncomfortable for some.

Frank discussions about racism in America, Booker said, could impact college football as a whole. The perspectives and knowledge gained by IMG players (roughly 85% of whom are Black, Acosta says), at a school that has produced more five-star recruits in the last five years than all but four individual states, would eventually permeate NCAA rosters from coast to coast.

“I want to have these discussions to show people and educate them on the oppression of people of color in this country … and then learn how we can collectively make a change so my kids don’t have to have that talk with their own football team,” says Booker. “I don’t want it to go away for now and have everyone forget about it; I want it to go away forever, so everyone can be seen as equals.”

Acosta asked Booker (who, before even taking a snap in his junior season, has scholarship offers from Alabama, Miami, Oklahoma, Penn State and USC, among others) whether he thought any college coaches were taking a similar approach with their own teams, or with recruits like him.

Based on his experiences, Booker said it was mixed. Some of the coaches he spoke to were honest with him, acknowledging what’s happening in America right now—the protests against decades of systemic racism—while others seemed to avoid the topic. But Booker also said he was tracking the way coaches engaged and responded more publicly, on Twitter, in the form of personal statements. Since he’s not able to visit prospective campuses because of the coronavirus, many of his early impressions of coaches and their programs have come from social media—namely, the way they responded to George Floyd’s death.

“I noticed which coaches came out and said something [early on]. … I made a mental note of that,” Booker told his coach. “I also made a mental note of the coaches who were late and seemed like their hand was forced to post something.”

Acosta asked whether the timing of those responses had changed his recruitment at all, and Booker didn’t say no.

He remembers saying: “I’m not just an athlete. I'm a person. … I want to know that the [coach] I'm putting my trust in actually cares about me as a person.”

For Booker to trust a coach, he says he needs someone who’ll accept him as a young Black man who sees what’s happening to other Black men in America. He wants from a college coach the same thing he wants from Acosta. Talk about it. Be honest about what’s happening. Don’t ignore this, even if it’s uncomfortable for some.

***

When Tyler Booker was in the fourth grade, he came home from his public elementary school in New Haven, Conn., with a yellow carbon-copied note and handed it to his parents. Tashona and William Booker knew that kids played sports during recess, and they knew football was the sport of choice during the spring. They also knew these yellow forms were handed out to children who’d been punished with a detention.

Thinking back on that moment is still difficult for Tashona. “It said on the form that Tyler was more aggressive today during recess,” she remembers.

She pauses, then begins again, her voice quivering. “ ‘Tyler was more aggressive today,’ ” she says. “Indicating that this kid is aggressive, but today he just happened to be even more aggressive.”

Tashona knew right then: Her son had been labeled.

She pulled him out of that school and enrolled him in a private one. A white friend—someone with a son at the same public school—said she couldn’t understand why Tashona was overreacting to such a small thing. But Tashona knew she wasn’t. It wasn’t small at all.

“This is where the system starts to shape the negativity with our young Black men,” she says. “They start to shape their character, and this young boy was ‘aggressive.’ Now he has a label. He's aggressive.”

The Bookers eventually landed at Bergen Catholic, a private all-boys school in Oradell, N.J., and Tyler shuttled back and forth between home and school on the weekends that fall of his 2018-19 freshman year, before deciding to transfer that winter to IMG. Less than a year later, Acosta arrived from Division III College of St. Scholastica, in Duluth, Minn., and one of his first action items, for a group made up of some of the most talented players in the country, was to create a leadership council. He sent a message to the entire team for the first meeting, but still he was shocked when every player showed up.

First to arrive at the meeting, sitting up front and taking notes, was Booker, who afterward had notes of his own for Acosta.

“My kids are young,” Acosta says, “but they're very mature. They feel they can change the world with what we do.”

***

Before he was Booker’s offensive line coach at IMG Academy, George Hegamin played seven seasons in the NFL, and before that with N.C. State. And there’s a story he has told in the following years. In 1991, he was a top high school defensive line recruit headed to—everyone assumed—the University of Michigan, which was coming off three consecutive top-10 seasons. But in the winter of his senior year he surprisingly picked a school that hadn’t finished in the top 10 in more than 15 years.

College football fans were shocked. While the Wolverines were fighting for national titles, the Wolfpack was fighting for relevance in the ACC.

When people asked Hegamin later why he’d chosen Raleigh over Ann Arbor, he told them it was a comfort thing. But it was more than that. He thought back to the day during his senior year when he arrived at the home he shared with his mother and grandmother, and found Buddy Green, a white coach, asleep on their couch—shoes at the door, legs kicked up, head knocked back. Hegamin looked at his grandmother in shock, but he remembers her telling him: “There are very few times that I have felt this comfortable around any white man, let alone a white man in my house.”

There was an openness, Hegamin says, in the way Green spoke about race and racism from the beginning of their relationship. The coach didn’t shy away from conversations that others seemed to find uncomfortable.

“Not one single time did he hide away from the differences that made him white and me Black,” says Hegamin. “When I think about the kids I coach, and I see the disconnect between them and the men recruiting them, it scares me.”

Hegamin has thought a lot about Green and his grandmother in recent weeks, wondering how many college coaches today could openly talk about race and racism with a woman who was born 30 years before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

When Hegamin first watched the video of George Floyd’s killing by police in Minneapolis, he flashed back to his own senior year of high school in New Jersey, when officers beat another unarmed Black man, Rodney King, on the streets of Los Angeles. He thought about those four officers’ acquittal. And he thought about that night at N.C. State during his freshman year when a few of his Black friends had joined him at a campus party, how the cops showed up, and how they treated the white students different than the Black athletes—and the Black athletes different than the Black non-athletes. He wondered: How many white coaches understand what that felt like?

“When I think of our [IMG players] going different places,” Hegamin says, “if they didn’t have on [their] teams’ colors, I don’t know how safe they would be as just regular people of color.”

As protests spread across the country, Hegamin texted and called all of his players, including Booker. He wanted to know what his star tackle was thinking, whether he was having open conversations with the men recruiting him. He wanted to know whether Booker had found his own Buddy Green yet.

Maybe yes, maybe no. There was one Black coach who called Booker and said simply: “Look, I know what you're going through. You’re a powerful Black man. I just wanted to let you know that I care for you.”

He’s had other promising phone conversations with coaches where he’s felt comfortable talking openly about oppression, about his concerns as a young Black man in America, about the fact that on a run a few weeks ago a white woman yelled at him from her yard and Ahmaud Arbery’s name flashed in his head.

But Booker has had a hard time focusing on those conversations—the ones that, though difficult, still felt good to have—because he’s had other talks where the coach on the other end of the line remained silent about what’s happening in this country, others in which he wasn’t asked about his experiences or fears, others in which a world outside of a football field didn’t seem to exist or matter.

“The conversations that stuck out to me the most,” he says, “are the conversations I didn’t have. … Some coaches kind of avoided it and acted like it's not going on. … They say they care about me—but if you really care about me, you should know that what is going on today affects me on a personal level. You should want to talk about that. You should want to see how I feel about that if you really care about me.

“Not just me as an athlete.”

***

In a normal recruiting season, herds of college coaches would have passed through IMG’s Bradenton, Fla., campus this spring to evaluate players. Booker would have met and spoken with them, and then he would have spent his summer following up with possible matches on campus visits, forming first (and second and third) impressions of coaches, their programs and college teams.

Of course, that didn’t happen. Booker was home in Connecticut for spring break when IMG notified students that, due to the coronavirus outbreak, the remainder of the year would be spent in virtual schooling, and that all further sporting events and practices would be canceled. Like his classes, college recruiting moved online, over phone calls and Zooms.

As a result, Booker hasn’t had as many conversations with coaches at this point in his recruitment as previous elite players have had. He’s left instead to form early impressions based on far fewer personal interactions, including on social media, where in the month since George Floyd was killed all walks of public figures—politicians, musicians, athletes—have weighed in, lending their voices to the protests and calling for racial equity and justice. Booker has been among the many waiting to see how (and if) college coaches engage publicly.

“Some coaches came out first, they led the charge,” says Booker, who’s holding a Twitter microscope to those recruiting him. “But it also seemed like some coaches were just following the trend. They seemed rehearsed. Some didn't seem sincere.”

More than reaction time, though, he has paid attention to the content of each coach’s response in gauging any degree of sincerity—and the content has certainly differed. The first college football coach to release a statement on Twitter following George Floyd’s death on May 25 was Indiana’s Tom Allen, who four days later wrote:

In the subsequent week alone, 56 other Power 5 football coaches put out written statements on Twitter or various other channels. (Coaches who quote tweeted or retweeted their own program or athletic director were included in this count.) SI examined those statements and found:

- The most commonly used word was change, 44 times.

- Next was Floyd/George Floyd/Mr. Floyd, which was cited 43 times. Thirty-one of the coaches’ statements, though, didn’t reference Floyd at all.

- The next three most commonly used words were: team (39 times), country (38) and coach (36).

- Some of the words most frequently used in protests were rarely found in those college coaches’ statements—words like violence (10 times), Black Lives Matter (three), police brutality (once), systemic racism (once) and inequality (once).

“I believe [coaches] are fearful of saying the wrong thing, not knowing that not saying anything is the wrong thing to do,” says Hegamin. “It’s like trying to cover up the elephant in the room, and it’s standing right there looking at you.

“It speaks even louder when they say nothing at all.”

***

Booker always knew that if he ever became a college athlete he would want to use his voice and platform for some good. But it was only in the last month—as student-athletes across the States have become noticeably more vocal, and as they’ve found results in using those voices—that he realized how important that role would be in deciding where he went to school.

“Wherever I end up, I want to make an impact on that community. I want my mark to be left on that campus,” he says. “So, I'm taking note of which schools and which players (from which schools) are starting to make an impact.”

What Booker has seen: In Mississippi, a June 22 tweet by Mississippi State running back Kylin Hill led directly to a vote last week in the state’s House and Senate to finally remove the Confederate flag from the state banner. At USC, Black student-athletes formed the United Black Student-Athletes Association to “use its position of influence to improve circumstances for the Black community within USC and beyond.” At Texas, student-athletes said they would withdraw from player recruitment and donor events unless several demands were met, including the athletic department donating 0.5% of its annual earnings to Black organizations and the Black Lives Matter movement. And at Texas A&M, quarterback Kellen Mond and receiver Jhamon Ausbon led a student-athlete push to remove from campus a statue of Confederate general Sul Ross.

Booker is not alone in watching, in knowing that he will someday use his platform for social justice work, in factoring this all into his recruitment. Says Tristan Leigh, a five-star senior tackle at Robinson Secondary School in Fairfax, Va., who’s undecided about where he’ll play next: “Student-athletes, we can use our voices so that people who aren’t heard—people who don’t have the same platform—get their views across too. I would definitely be a part of something like that.”

Ceyair Wright, a four-star senior cornerback from Loyola High, in L.A., is also undecided about where he’ll play—but he’s already using his platform, having created a video with his father that begins, “The Top 2021 and ’22 Football Recruits in California Speak Against Police Brutality and Racism.” Among the 18 high school players who lent their faces and voices: Korey Foreman, the No. 1 prospect in the ’21 class, who is undecided, as well as others planning to play football at the likes of Notre Dame, LSU and Washington.

These young men know that, even before they set foot on campus, their voices matter. The top 15 recruits from that 2021 class average a combined 22,000 followers between Twitter and Instagram. And with continuing protests against systemic racism, along with a fall election that seems certain to further stoke racial tensions, it’s almost a given that college athletes will speak out on matters of race and racism.

As Tyler Booker looks for the college football program that fits him best, he’ll seek one that not only elevates its players’ voices but also engages in the national conversation. He needs a coach he can trust, and that means someone who tries to understand players and their experiences away from the field. He needs to find his own Buddy Green.

Until he does, he’s going to watch and see which coaches talk honestly and openly about what is happening in America, which coaches want to have a conversation even if it’s uncomfortable. And he’s going to see which coaches stay silent on those matters, knowing that silence speaks pretty loudly, too.