Sanders has grand plans for restoring Jackson State—and HBCU football in general—to national relevance. He'll have no shortage of buzz while attempting it.

JACKSON, Miss. — On the outskirts of Mississippi’s capital city, customers entering a Dick’s Sporting Goods are greeted by a rack of apparel belonging to one of the state’s college football programs.

The rack is full of blue and white hats and shirts, not red and blue for the Ole Miss Rebels or maroon and white for the Mississippi State Bulldogs. The depiction of a tiger streaks across sweatshirts and three letters crawl across the ball caps: J-S-U.

Usually, Jackson State apparel is located toward the back of the store. Not today.

“We put it in the front after the announcement,” says Josh Eide, a 40-year-old store staff member.

The Dick’s Sporting Goods is located in a giant shopping center in a suburb of Jackson called Flowood, a mostly affluent, white area outside of a predominantly Black city. Eide says Jackson State merchandise is flying off the racks since the school announced the hire of its new head coach: Deion Sanders. In fact, Eide himself is eagerly awaiting the arrival of Sanders-themed apparel branded with the coach’s self-coined moniker: Coach Prime.

“I’m sure it’s on the way,” Eide says. “I’ll be buying my jersey.”

The ripple effect of Sanders’s stunning hire as the new head coach of this historically Black college football program has already made its way across Jackson, the state of Mississippi and the country. The school estimates it has received $12 million in media exposure. For instance, Sanders has been featured on television shows such as Good Morning America.

Donations to the school are spiking. On the opening day of season ticket sales last Thursday, hundreds of people formed a line that wrapped around the team’s football stadium. Enrollment is seeing an impact, too, with interest from students who wouldn’t normally consider the school, JSU leaders say.

The Deion effect has even extended to headquarters of the Southwestern Athletic Conference in Birmingham, where commissioner Charles McClelland has fielded calls from television producers about filming a reality show featuring Sanders and Jackson State.

“The SWAC,” McClelland says, “is on peoples’ minds.”

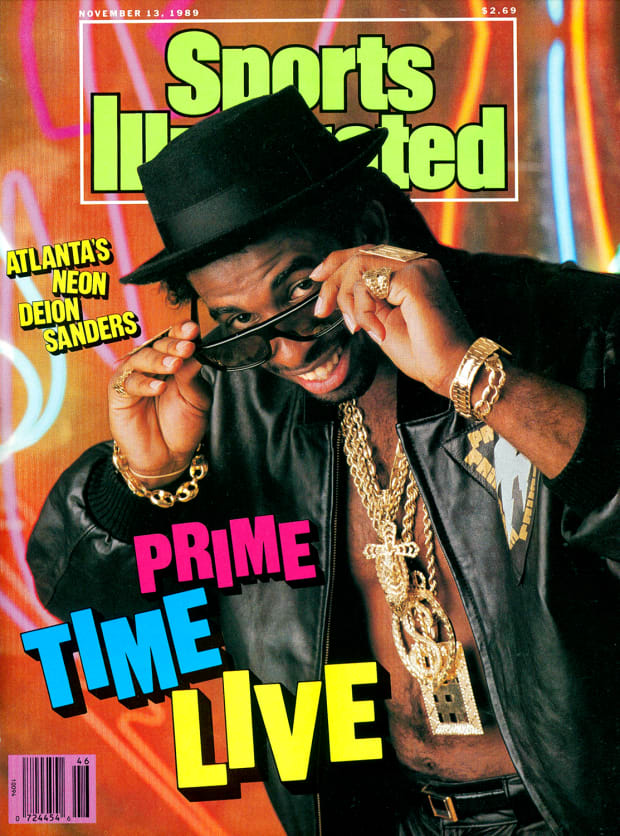

In an unprecedented hire in college football history, Sanders brings to Jackson State zero college coaching experience and millions of college football eyeballs. Widely known for his skills during a 14-season NFL career, the former cornerback and return man, dubbed “Prime Time” by his peers, has spent his post-playing days coaching at the high school level and, most notably, dabbling in the media world—a gregarious analyst on NFL Network and CBS Sports who most recently signed a deal as a contributor for the outlet Barstool Sports. In fact, Sanders has his own podcast on their network.

While acknowledging the hire was made in part for media exposure, Thomas Hudson, JSU’s acting president, says the attention has exceeded even his lofty expectations. “I had no idea it would be as big as it is.”

Now comes the hard part: resurrecting the JSU brand, tarnished over the decades, while restoring respectability to the SWAC and all of Black college football. Once factories for NFL production, historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) have withered over time, many of their facilities in disrepair, their budgets squeezed and their rosters mangled.

They have been surpassed, McClelland admits, by richer football programs. Sparked by integration in the 1970s, highly touted high school prospects now flock to schools with lavish facilities, big-name coaching staffs, mega stadium crowds and the bright lights of network television broadcasts.

But those in the HBCU world say change is on the horizon. Buoyed by the social justice movement sweeping across America, Sanders appears to be maneuvering himself as the leader of a similar movement in college sports that, he says, seeks equality. He’s the new brash, trash-talkin’ face of Black college football, possessing an NFL Hall of Fame résumé and more star power than anyone in the HBCU realm has had in decades.

“With what we’re doing in the country—social injustices, so many things about trying to reach and strive for equality—this is the best possible scenario and situation I could ever find myself in,” Sanders tells Sports Illustrated. “It’s a task to me—level the playing field.”

***

Last year, after firing coach Chad Morris, Hunter Yurachek’s cellphone buzzed with the name of a sports agent. For the athletic director at Arkansas, who was beginning a coaching search, this wasn’t unusual.

“I need you to at least talk to this guy about the position,” the agent told Yurachek. “Deion Sanders.”

Deion Sanders?!

Yurachek obliged. He interviewed Sanders for the head coaching job at Arkansas.

“I was thoroughly impressed with Deion,” Yurachek says. “I didn’t think this was the right starting point for him as a collegiate head coach in the SEC, but I think Jackson State is a great landing spot. Some are going to say this is a publicity stunt. Yes, it’s going to sell more tickets, but the time I was able to visit with Deion, he knows football.”

At some point last fall, Sanders expressed interest in cracking into college coaching to his business manager, Constance Schwartz-Morini, a co-founder of SMAC Entertainment, a talent management company launched in 2010 with former NFL star Michael Strahan.

Schwartz-Morini brought sports agent Jordan Bazant, who represents several high-profile college coaches, aboard to her team. They got to work. Schwartz-Morini says Sanders’s team at SMAC numbers around a dozen people, all of them preparing their client for somewhat of a career change. They helped him craft a thick binder that included his organizational plan, potential coaching staff members, long-term goals, etc.

Among those in the coaching search firm world, Sanders became a serious name, says Gene DeFilippo, a former college administrator and now the executive director of Turnkey Sports and Entertainment, one of the most widely used coaching search firms. DeFilippo communicated with Sanders last winter, giving him advice ahead of job interviews. He left those conversations genuinely pleased with Sanders’s plan. His pursuit of coaching is rooted in the “right reasons,” says DeFilippo.

Sanders didn’t only land that interview with Arkansas, but he also spoke to officials at his alma mater, Florida State, last year about their opening, something he’s made public in the past. Sanders describes interviewing for jobs as a daunting task. “It’s a whole new endeavor,” he says.

The connection between Sanders and Jackson State happened well before JSU athletic director Ashley Robinson dismissed coach John Hendrick on Aug. 31. In fact, the courtship started as far back as the Senior Bowl in January, says C. Daryl Neely, a Jackson native and prominent JSU booster. The two, Sanders and JSU, courted one another for months in what was one of the best kept secrets in Jackson only because, Neely laughs, “no one actually believed it.”

Sanders, the offensive coordinator for Dallas-area Trinity Christian Academy, where his son plays quarterback, took a visit to JSU’s campus over the summer and again when Trinity played a game on Aug. 21 against Madison-Ridgeland Academy, about a 25-minute drive from the JSU campus. They finalized an agreement over the course of the next few weeks.

Sanders’s hire fits in with a recent string of hires in this football-crazed state, says Robinson, JSU’s 41-year-old AD. Ole Miss and Mississippi State both fired coaches last offseason in somewhat surprising moves, only to hire splashy names with eccentric personalities and creative offenses: Lane Kiffin in Oxford and Mike Leach in Starkville.

Robinson took a bigger leap than even those schools. But he believes he’s starting a new trend in the college football world, hiring what he calls a “CEO” and media magnet to operate a program.

“On [the AD] level, we don’t look at that hard enough, don’t look at the bigger picture,” he says. “Everybody I talk to is saying now is the time to do this. You’re doing something nobody thought about doing or nobody had the guts to do. I think this will start something.”

DeFilippo can’t quite equate the Sanders hire to any other in recent college or pro football history, but there are commonalities in other sports. For instance, at the NBA and MLB level, ex-players with little or no coaching experience have been hired by the New York Yankees (Aaron Boone) and the Brooklyn Nets (Steve Nash).

Football, though, is different, DeFilippo notes. The logistics of managing a college team of more than 100 players and at least a dozen more staff members presents hurdles that basketball, baseball and even the NFL don’t.

“It’s not like you’re putting five people on the court,” DeFilippo says. “I’ve never seen anything like this. I hope it works out.”

Since the announcement, Robinson has heard from other athletic administrators across the country, many of them heaping praise on him for making such a bold and unconventional hire. That includes Yurachek, whom Robinson calls a mentor to him in the industry. Yurachek describes Robinson as an outside-the-box thinker and a young up-and-comer in the athletic administrative industry. He recently became the first Black president of the FCS Athletic Directors Association.

While Yurachek defends his friend’s decision, Robinson has also heard the opposite.

Deion Sanders?! Are you out of your mind?

“People ask questions, ‘Well, you can’t control him,’” says Robinson. “For me, it’s not about control—it’s about working together as a team.”

Sanders isn’t your prototypical SWAC coach. For instance, interview requests for Sanders are, at least for now, run through a marketing team mostly based in Los Angeles and led by Schwartz-Morini. Secondly, he doesn’t start the job officially until Dec. 1.

Sanders will complete Trinity Christian’s 2020 high school season before moving to Jackson full time to prepare for a shortened spring season that’s slated to start in February. The Trinity Tigers, currently 4–2, are scheduled to play their last regular-season game on Nov. 20. Because of NCAA rules, he cannot actively operate as Jackson State’s head coach until the high school season ends, Schwartz-Morini says.

For at least another two months, he’ll focus on fatherhood. As offensive coordinator at Trinity, he oversees his youngest son, starting quarterback Shedeur Sanders. Deion says he’s turned down college and pro assistant coaching jobs in the past because of his boy.

“Oftentimes when we lacked something as a child in our childhood, we want to over-compensate for that in which we lack,” Sanders says. “Therefore, I wanted to be the greatest father ever. I feel like I’m in the process of doing such a thing.”

During various interviews over the last two weeks, Sanders has produced only vague answers as it relates to his schematic plans for JSU. His offense will operate from the spread and involve heavy “movement.” His defense will be aggressive, attacking and physical with an eye toward the end zone for those elusive defensive touchdowns.

“And when we score,” Sanders said during his introductory news conference, “we’re going to celebrate.”

***

While touring the Jackson State football facilities—the practice field, the locker room, the coaches’ offices—Maurice Hampton and his son, four-star recruit Maurice Hampton Jr., both came away with a similar impression.

We’d seen better facilities at high schools.

“A lot of kids won’t come to JSU because their high school facilities look better,” says Maurice Hampton Sr., himself a Jackson State football player in the 1990s. “My son grew up going to Jackson State games, but you get on the recruiting trail and go to all these SEC schools and mid-majors and come back to us …”

Maurice Hampton Jr., a dual-sport athlete in football and baseball who did consider Jackson State, now starts at safety for LSU.

Maurice’s father played at Jackson State during the back end of what’s known as the program's golden years. From 1961 to 1996, JSU won roughly half of the SWAC championships (15). Under coach W.C. Gorden in the 1980s, the program turned into a perennial HBCU powerhouse, at one point reeling off a 28-game regular-season win streak.

The Tigers have produced more than 90 NFL players and four NFL Hall of Famers, including running back Walter Payton. They regularly lead the FCS in attendance, last year recording an average of 33,762 fans for home games at Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium, a 60,000-seat venue located off campus.

However, the program has slipped into decline, especially over the last decade. The Tigers haven’t produced a winning season since 2013 or an NFL draft pick since 2008. Sanders represents the fourth new head coach at the school in seven seasons.

Outside of its mammoth stadium—itself 70 years old—facilities are lagging behind even lower-level SWAC programs, former coaches say. Talent has dropped off considerably, too, and winning has gone with it.

In a way, Jackson State is a microcosm of Black college football’s decline in America—a 30-year downward trend that experts say began with integration in college football in the 1970s, a theory backed up by jaw-dropping data. Over four decades, from 1960 to 1999, the SWAC produced 196 NFL draft picks, including 55 first- or second-rounders. In the last 20 years, the conference has produced 26 draft picks and four first- or second-round selections. Some schools haven’t had a player drafted since the 1990s.

“It’s obvious what happened when integration hit,” former SWAC coaching legend Marino Casem said during a 2011 interview. “The larger schools started zeroing in on the African American athlete. The historically Black institutions, which had a monopoly, had to fight among themselves, fight to get reasonable athletes. That was the downfall, the weakening.”

McClelland points to money as the most recent issue. SWAC athletic department budgets are a fraction of those on the FBS level, ranging from a high of $19 million to a low of $4 million, according to figures from USA Today. At least two of the conference’s 10 members do not sponsor the full FCS maximum of 63 scholarships for football, McClelland says.

Money is tight enough that the conference more than 20 years ago relinquished its automatic bid into the FCS playoffs, instead creating a championship game now played at the highest division champion’s stadium. The league’s on-campus title game can generate upwards of $2 million for the host institution.

McClelland says the SWAC is still eligible to receive an at-large berth in the playoffs, but the two teams participating in the championship game are ineligible, as the title game kicks off after the playoffs begin. Jackson State was the last team to compete in the FCS playoffs, losing to Western Illinois 31–24 in 1997. The SWAC has never won a single game in the playoffs. In fact, the only HBCU to have won a playoff game this century is Tennessee State.

Asked about competing in the FCS playoffs, Sanders turns the conversation to something else: participating in bowl games. Jackson State is in the FCS, not the FBS, the highest tier of college football where teams compete in bowl games. He believes that’s unfair.

“Why in the world would HBCU football not be invited to a bowl game?” he asks. “You have some colleges that are 6–6 or 7–5, barely won and nobody wants to see them on television to save their life, but they get invited to a bowl game. Do you know what that would do to our kids and any HBCU to be invited to a bowl game?”

Sanders’s primary way to revive Jackson State became clear quickly: recruiting.

Within hours of his introduction as coach, Sanders offered scholarships to a host of highly ranked prospects, athletes that Jackson State and SWAC programs normally don’t pursue because of their stature. The list includes the second-ranked offensive tackle in the country, the seventh-best receiver, the top-ranked player in Louisiana and, naturally, his own son. Shedeur Sanders is a four-star prospect who is committed to FAU.

Offers do not equate to commitments or signings, but Sanders’s mission is clear: pursue the best players.

“If a kid is good enough for a Power 5 school, why isn’t he good enough for us?” Sanders asks. “A lot of players don’t give HBCUs an opportunity. First and foremost, they’re not recruited to go to HBCUs. I don’t know where we started thinking HBCUs are beneath us as a people.”

He has gotten one commitment, at least. The same week of his hire, Mississippi State freshman defensive back Javorrius Selmon, ranked last year as the 18th-best recruit in the state of Mississippi, announced he’d be transferring from MSU to JSU to play for Sanders.

More could be on the way. The Black Lives Matter movement has led to several examples of this transpiring across the country. Athletes who may have never considered playing for HBCUs are at least toying with the idea. Some of them are even making commitments.

Noah Bodden, the top-ranked quarterback in New York City, plans to sign in the 2021 class with Grambling State, passing on FBS offers from the likes of Baylor, Cincinnati and Arizona State. Five-star basketball prospect Makur Maker announced in July that he planned to play his college ball—well, at least one season of it—at Howard.

This used to happen more often. Everyone has a different theory about why recruiting at HBCU levels slowed so tremendously over the years. Some believe the 13 football-playing junior colleges in the state of Mississippi have siphoned talent from the three in-state SWAC schools. Hampton says the FBS’s Group of Five programs, through increases in expenditures and exposures, have landed athletes who used to attend HBCUs.

Sanders says he does plan to use his own personal resources at JSU. He hopes to reach out to the NFL as well, even suggesting that the league could help fund a new practice field at Jackson State.

“Have the NFL put their money where their mouth is,” he says. “I’m an NFL legend. There are funds for that. We have several NFL legends going to be on the coaching staff, so if the NFL is not going to support that, that’s a problem.”

The facilities are the real issue. In fact, former JSU coach Harold Jackson says he avoided touring prospects through them during recruiting visits in 2014–15. Specifically, he didn’t want prospects seeing the program’s team meeting room and its seating arrangement: metal folding chairs. The recruiting budget was so tight that many of Jackson’s assistants refused to recruit at all. They couldn’t afford air travel, at times couldn’t stay in hotels, and didn’t receive travel reimbursements for months, he says.

However, improvements have been made. Robinson took over the department in 2018 and immediately increased the budget enough to afford air travel for recruiting, says Hendrick, Sanders’s predecessor who was fired in August but is still on contract with the school until December. The school even planned to construct a football-only building as part of an addition to the on-campus Walter Payton Center. The COVID-19 pandemic, though, slowed progress on that, Hendrick says.

“Jackson State is probably on par with other HBCUs, but maybe not facility-wise,” says Hendrick, who has worked at seven different HBCUs during his 37-year coaching career. “I thought the facilities were even better at (Arkansas) Pine Bluff and South Carolina State.”

***

The mayor of Jackson, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, may have been one of the first people in the city to learn that Sanders could seriously become the next coach at Jackson State. He had a source on the inside, he chuckles.

“I heard the potential of Deion coming about four months ago,” he said during an interview with SI in late September. “I had a good friend helping to make it happen. It was clear [Sanders] not only wanted to be part of the institution but the community at large.”

The city of Jackson and the university hold a symbiotic relationship. JSU’s campus is but a mile from the city’s downtown, lined with government buildings, restaurants and hotels. The city’s biggest revenue-producing event each year is a Jackson State home football game.

Jackson is “buzzing” with Sanders’s hire, Lumumba says, and both school and city officials have discussed the economic prospects of his time in Jackson. They’re hoping Sanders’s connections could benefit an economy that, like many in America, is reeling amid the pandemic.

The hiring has already reignited what’s been a decade-long conversation about building the school an on-campus football stadium, Lumumba says. Located adjacent to the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Veterans Memorial Stadium has landlocked the hospital from future expansion.

On campus, meanwhile, Sanders’s connections are already generating benefits from his high-placed friends. Former NFL star Michael Strahan is planning to donate to the school dress suits for players to wear during road trips, Sanders says. The school and city are focusing on maximizing Sanders’s stay in Jackson, knowing it might not be a long-term affair. After all, the days of coaches settling into a job for a decade or more are over.

“There’s going to come a day where Coach Prime is not the active head coach at Jackson State,” Neely says. “How do we maximize this time so the next coach isn’t starting from the ground?”

The university is hoping, for one, that donations increase. During its founding in 1877, Jackson State’s original mission was churning out Black preachers and teachers. It only became a state-supported public institution in 1940.

While other state schools possess a long lineage of wealthy alumni giving lines, Jackson State does not, Neely says. In the latest data sent to JSU supporters, the school says just 3.7% of its alumni contribute to the university. Roughly 3,000 donors gave $4.7 million in 2019–20. For comparison sake, donors at Ole Miss gave more than $100 million to the institution each year from 2011–2017.

“Nothing against the people who do make small contributions, but unless you win, our donor base keeps their money in the pocket,” says Eddie Payton, Walter Payton’s older brother and the longtime golf coach at JSU who retired in 2016 as one of the SWAC’s winningest coaches in any sport. “Hopefully Deion will incite them to dig deeper into their pockets.”

JSU has battled more issues than a lack of booster giving, Payton says. Coinciding with the football’s team’s on-field slump is serious administrative turmoil at the very top level of the school. JSU is on its third athletic director since 2012. Vivian Fuller was “reassigned” after facing numerous lawsuits, including one that ruled in favor of the plaintiff, another that was settled and three that were dismissed. Fuller’s replacement, Wheeler Brown, was relieved in 2017, two years into a three-year contract.

A year before that, the school’s president, Carolyn Meyers, resigned amid financial issues. Over the final five years of her tenure, JSU’s cash on hand had plummeted from $37 million to $4.2 million. The next president, William Bynum, lasted less than three years. He resigned this spring following his arrest in a prostitution sting at a Mississippi hotel.

Sanders has found his own problems in the past. A group of charter schools he co-founded in Texas, Prime Prep Academy, closed in January 2015 due to financial insolvency after years of allegations that included theft, unpaid rent that led to students being evicted, influence peddling and failing to hold open meetings. At one point, Sanders pressured his co-founder, D.L. Wallace, out of leadership and called him a "snake," and shortly thereafter Sanders himself was fired as head football coach."

“No concern about that,” Hudson says when asked about Prime Prep. “Coach Prime, he’s here to coach football and bring our football program to the next level. I’ll continue to make sure our university remains stable academically.”

Those around the Jackson State community express confidence in the leadership of Robinson and Hudson. The athletic department is marching forward, they say, with a facilities improvement plan to coincide with Sanders’s hire. This administrative support is imperative. Sanders’s five predecessors “were asked to do so much with so little that they ended up doing nothing and got fired,” Payton says.

Things are looking up here now. Sanders has sparked interest in Jackson State from across the country like it hasn’t received in decades, maybe. Apparel is flying off racks, those season ticket lines are wrapped around buildings, recruits are buzzing about Coach Prime and, maybe most important of all, JSU and Black college football believe they have found their savior.

It’s Prime Time.

“I want to restore HBCU football,” Sanders says. “I’m all in. It’s not one foot in, one foot out. This job is certainly not beneath me. I look forward to the challenge.”