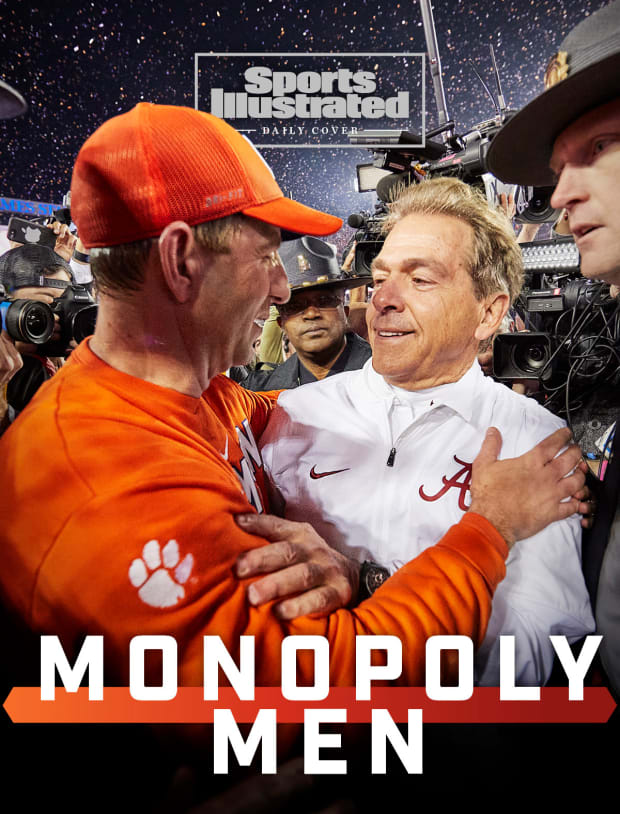

The sport's playoff has become an exclusive playground for Alabama, Clemson and a few other powerhouses.

One of the greatest offensive minds in the history of college football happens to belong to one of the sport’s most braggadocious men, and today Steve Spurrier is especially eager to crow. He waves a visitor into his cozy office in the bowels of the stadium with a field named in his honor on Florida’s campus and kicks off the conversation with some playful boasting. A friend, he says, just told him about an interesting footnote to his iconic coaching career.

Did you know, he starts off, that the 1996 Gators, the Spurrier-coached group that went 12–1 and produced a Heisman Trophy quarterback, is the last first-time national champion in college football?

“That’s been 25 years,” the Head Ball Coach says through a smirk.

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

It’s true. A quarter century has passed since we’ve seen a program win its first title, a startling drought that’s just one more indicator of a trend that upstart schools from coast to coast are all too aware of: Parity is pretty much dead in college football. Since Florida announced itself as a national power, a small group of teams has done more than dominate the postseason—it has strangled any sense of competitive balance in the sport. Beginning in 1998, the first year of the BCS and the dawn of the era when national championships are decided on the field and not in the polls, six teams have combined to win 74% of the championships: Alabama (6), LSU (3), Clemson (2), Florida State (2), Florida (2) and Ohio State (2). In the last 23 years, just 17 teams have qualified for the 46 spots in championship games.

The Playoff era, which began with the 2014 season, has been even more exclusive. Four teams—Alabama, Clemson, Ohio State and Oklahoma—have accounted for 20 of the 28 playoff spots (71%), and the Tide, Tigers and Buckeyes have combined for 11 of the possible 14 championship game berths. Last season marked a new extreme in the imbalance of the sport. For the first time in the seven years of the Playoff, none of the four participants were making their first appearance in the four-team bracket.

The same teams are appearing so regularly that college football’s executives proposed a 12-team playoff expansion model this summer, largely to inject new blood (and yes, even more revenue) into a stale system. Fans may be growing bored with the same old teams, too: Alabama’s win over Ohio State in January drew the lowest title-game TV audience of the CFP era.

“I think it’s a problem,” says West Virginia coach Neal Brown. “It’s a problem for our sport, and we’ve got to figure out solutions.”

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

As an assistant coach with Notre Dame in the mid- to late 1980s, Barry Alvarez never once got turned down for a visit to a prospect’s family home. “I could get into anyone’s living room and have a legit chance to sign them,” he says.

Then he took over as head coach at Wisconsin in 1990, and that all changed. “The big brands get the best kids,” says Alvarez, now a special adviser to the Big Ten, “and when you’re winning championships, that’s where the best players want to go.”

Recruiting is the lifeblood of college football, and it offers the most prominent example of how the sport’s unofficial caste system of Have and Have-not programs has become a self-perpetuating parity destruction machine. If you have a rich championship tradition, you probably also have overflowing coffers, a large fan base and lavish facilities—all the better to impress top recruits who will help you add to that championship tradition.

Of those six teams that have won three-quarters of the national titles since 1998, five rank in the top 12 nationally in athletic department budgets, according to 2019 figures from USA Today. (Clemson is the outlier at No. 22.) And of those six schools, five are part of a group that has reeled in the best talent in the nation over the last decade. In a study from MaxPreps, seven programs have signed 55% of the five-star prospects since 2011. They include LSU, Alabama, Clemson, Florida State and Ohio State, as well as USC and Georgia.

Once, schools around the country could count on a reliable pipeline of talent from their own backyards, and even the biggest programs kept their focus local.

(Bear Bryant’s last Crimson Tide championship team, in 1979, featured 71 players from Alabama and just 37 from elsewhere, including none from Texas or California.) And if you’re lucky enough to coach a school in the Southeast, you can still build a pretty good roster with regional talent. The SEC’s 11-state footprint has produced 197 five-star prospects since 2011. The other 39 states have churned out 134. (Oklahoma, which has produced two five-star prospects in that span, will soon give the SEC a 12-state footprint.) The South’s grip on college football and its talent pipelines has never been stronger. No wonder schools from Southeastern states have won 14 of the past 15 titles, the outlier being Ohio State.

But thanks to years of postseason visibility, massive social media followings and bottomless budgets, big-brand schools are making the recruiting gap between the Haves and Have-nots even wider. For a select few programs, the entire country is now the backyard. For instance, the Crimson Tide’s last two signing classes have featured 13 players from the state of Alabama and a combined 20 players from Florida and Texas. The Tide got three players from Maryland and three more from California. Its national reach has helped Bama build the country’s No. 1 recruiting class in nine of the last 11 years.

“It’s almost unfair,” says Spurrier. “At Alabama it’s like being in the NFL, winning the Super Bowl and every year getting the first 10 picks in the first round.”

It’s a cycle that is choking meaningful competition. “If you win a championship in the NFL, you’re picking last,” says Stanford coach David Shaw. “If you win the championship in college football, you’re picking first. There’s nothing that helps the people in the middle get to the top.”

So, today’s blueblood programs are stronger, richer and more powerful than ever. But despite what Shaw says, there are a few factors that could help level the playing field.

• The transfer portal. Players can now transfer and play for a new team immediately, making it easier for talent to spread. A school that is one or two pieces short of a championship-caliber team can dip into the transfer portal, sign a player and immediately plug him into the hole.

• Clever schemes. On its own, offensive innovation can spark a charge at the big boys. “Scheme can close the gap with the Haves,” says Gerry DiNardo, the Big Ten Network analyst who was offensive coordinator for the Colorado team that won the 1990 championship, one of the last nontraditional football powers to win it all. They recruited well and were stocked with future NFL talent, but the Buffaloes also developed an exotic offense by meshing the I-formation with the Wishbone option. The I-Bone powered them to that 11–1 season.

But since then, the Buffs have won two conference titles in 31 years. It’s a familiar pattern: Just in the 2000s, see West Virginia under Rich Rodriguez and then Baylor under Art Briles and Oregon under Chip Kelly. “There’s a chance a Have-not can break through, but they won’t sustain it,” DiNardo says.

• Committed coaches. One reason for DiNardo’s skepticism about sustainability: Innovative coaches who turn middling programs into winners often bolt for bigger jobs. But long-term program success is connected to consistency at the top. Only 10 coaches in major college football have coached at their respective schools for at least 10 years, including Saban (15 years) and Dabo Swinney (14 years).

Baylor coach Dave Aranda believes one of his Big 12 rivals, Iowa State, is on course for a program breakthrough based on its coaching consistency. “There have been teams that have shown the ability to contend, but the coaches leave after their success,” Aranda says. “The ability to do it and build and build, I think, is uncommon. Matt Campbell is doing it now. ”

Now entering his sixth season leading the Cyclones, Campbell has turned down high-profile jobs to remain in Ames and continue building Iowa State. This past offseason, he said no to a $68 million offer from the Detroit Lions, and in previous years he’s been linked to openings at several high-profile schools. Along the way he has led the Cyclones to four straight bowl games—a program first—including a win over Oregon in the Fiesta Bowl last January. Iowa State was No. 9 in the final AP poll, its highest finish ever, and in 2019 and 2020 it broke into the top 50 recruiting class rankings. “You’re always trying to figure out: How do you find consistency?” Campbell says. “To be quite honest, you’re in an uphill climb.”

Richard Rodriguez/Getty Images

• An expanded postseason. Oregon coach Mario Cristobal, a former Saban assistant, believes he’s identified the recipe for success in college football: (1) recruit well; (2) develop players; and (3) use those players appropriately. “That’s how Clemson got so successful, right? That’s how it works,” he says. “That’s the blueprint proven over time.”

Sometimes it takes a little luck, too: Two years ago, Oregon finished 12–2 but fell a field goal short of a likely spot in the four-team playoff. Plenty of programs have been one play from the promised land in the Playoff era. How could anyone forget Big 12 cochampions TCU and Baylor, both 11–1, being left out of the 2014 playoff? In ’15, Stanford and Iowa were just on the outside looking in. Last year it was one-loss Texas A&M and undefeated Cincinnati.

In June, the College Football Playoff Board of Managers approved a feasibility study for an expanded, 12-team playoff system that would include six major-conference champions and six at-large teams. Broadening the postseason might help teams outside of the Bama-Clemson–Ohio State–Oklahoma axis break through. “When’s the last time you saw a school become a new brand in football?” asks Notre Dame AD Jack Swarbrick, who was part of the committee that formed the expanded playoff proposal that will be studied. “We’ve seen Gonzaga become a brand in college basketball. Football is such a high-resource sport. There’s such a high investment to get to that level. The commitment you have to make is hard for universities.”

The only way to create that investment is to build the kind of program profile that comes with national titles, or at least regular postseason exposure. “To crack the code to create parity, you’ve got to get into the playoff, and you’ve got to win,” new Texas coach Steve Sarkisian says.

There are more far-fetched ideas for creating parity. Some have suggested limiting college programs to a certain number of four- and five-star recruits. Others say the NCAA should reduce scholarships from 85 to 70 to disperse more talent across the country. Kyle Whittingham, the longtime coach at Utah, believes parity can be achieved only if a 30- or 40-team superleague forms with equal revenue distribution to all members. (The SEC, with its plans to add Oklahoma and Texas, may be heading down that path.)

Until that happens, coaches outside of college football’s power circles are relying on the tool that has rallied programs and fans throughout the game’s history: hope. “I do believe there’s enough wins for everybody,” says Baylor’s Aranda. “Instead of trying to be like those [blueblood] teams, be who you are and make your place unique and reflective of you so that it becomes important to other people.”

In the meantime, here's Sports Illustrated's preseason top 25. The teams at the top might sound familiar.