A pair of concussions. Uncontrollable emotions. An altered personality. A crucial diagnosis. Olympic wrestler Helen Maroulis opens up about the injury and brain trauma she's had to overcome in her bid for the delayed Tokyo Olympics.

Helen Maroulis was a shy seven-year-old kid growing up in Maryland when her younger brother, an aspiring wrestler, needed a sparring partner. She hit the mat with him in her pink ankle socks, beginning a wild journey that eventually took her to the 2016 Olympics—where she became the first ever female wrestler to win gold for the U.S. Now she hopes to win it again.

“I think I can make it all the way,” she says, describing her hopes for the Olympics in Tokyo, which have been postponed to next July due to the coronavirus. She is well on her way, having qualified for the finals of the U.S. Olympic Team Trials. But getting to this point has been a battle—one of many over her lifetime.

Her story is one of phenomenal perseverance through a series of roadblocks that would have stopped a less driven athlete, starting from the time she was a child, wrestling against boys amid a lack of teams for girls. Most recently, the 28-year-old Olympian has had to fight her way back from injury and brain trauma that actually changed her personality for a time.

Maroulis is refreshingly honest about the physical and mental hurdles she has faced. She says she wants kids to understand that Olympic athletes are human. “I used to think Olympians had superpowers,” she says. “That’s how the media talks about them. I don’t want young kids to think you have to be so perfect. You win with your strengths and weaknesses.”

Her most recent—and perhaps most challenging—battle began in 2018.

Early that year, at a three-week international wrestling league in India, she knocked heads with an opponent. Afterward, feeling off-kilter, she wondered whether she had a broken nose, or jet lag from the long-haul flight, or possibly a concussion. If she did have a concussion, she thought she knew what to expect, as she had experienced one in 2015 that she had quickly overcome.

She tried to rest as much as possible, but after her third match, she felt disoriented and knew something was wrong. She asked to see a doctor, who gave her some medications that he said were for nausea. The pills left her feeling “out of it,” she says, unable to think straight.

Her Greek American father, Yiannis Maroulis, who had been watching her compete online from home in Maryland, also saw that something was wrong. “She didn’t look like herself,” he says. “She would wrestle and then look around, like, what am I supposed to do next? I called and said to stop; I texted her coach and said something’s wrong with her.”

She called two doctors in America via FaceTime. They gave her mixed messages. One advised her not to continue, while the other said she could keep going if a doctor monitored her. She kept in touch with the Indian doctor and spent much of the next couple of weeks sleeping, not wrestling. When it came time for the semifinal and final rounds, she felt obligated to compete. She had developed a sensitivity to sound, so before the matches, she hid in a quiet bathroom, putting cotton balls in her ears for the competition. In retrospect, Maroulis says that throughout her experience, it was as if she were in a state of delirium.

When she returned to the States, she consulted with specialists, who officially diagnosed her with a concussion. But this concussion turned out to be very different from the mild one in 2015. In addition to causing fatigue and sensitivity to light and sound, it affected the part of the brain that controls emotions, altering her personality. A self-described “very emotional” person before the concussion, she found herself becoming “super-direct and logical,” she says. She recalls that a doctor told her, “I can get you back physically, but I can’t guarantee your personality will ever go back to normal.”

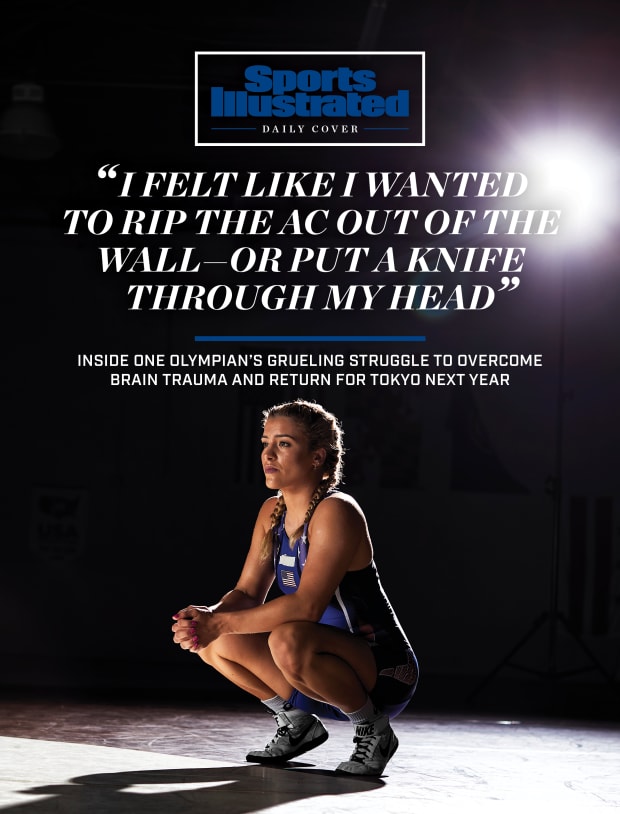

Over the weeks, a range of emotions did arise, but they were emotions that felt uncontrollable as her brain tried to deal with its new sensitivities—such as the sound of people singing at church, or the buzz of her air conditioner. The noise seemed unbearable. “It was like I would flip a switch and become a different person,” she says. “I felt like I wanted to rip the AC out of the wall, or put a knife through my head.”

With the help of specialists from across the country, she immersed herself in an intensive physical and mental treatment regimen—including noise-canceling headphones, special vision-correction glasses, a gluten-free diet, supplements such as fish oil and sessions with a psychologist. The routine was all-encompassing. For instance, she had to wear the headphones around the clock—and eventually, she had to wean herself from them. “I would try to go for five minutes at a coffee shop without them, then go home and see if I had symptoms,” she says.

After a few months, she began to feel more like herself—or so she thought. Looking back now, she realizes she had not fully recovered at the time. She was cleared to resume training, then got walloped with another concussion and a neck injury while sparring with an aggressive male coach, she says, resulting in severe vertigo and problems with her autonomic nervous system. She got treated for several months and was cleared to train again, but struggled to regain her equilibrium. “While lifting weights, if I strained my neck, I would have these episodes where I would hyperventilate, shake and cry, but I didn’t have any emotion toward it,” she says. “I didn’t know what was going on.”

Finally, sport psychologists gave her the diagnosis that helped her put everything into context: She had post traumatic stress disorder.

She knew she was in for a major fight.

***

Maroulis learned from an early age that she would need to fight hard if she wanted to pursue wrestling. From the time she first tussled with her brother back in the ’90s, she loved the sport and wanted to advance—but not everyone was supportive of her ambitions. When she began wrestling against boys in a local youth league, the coaches didn’t like it and tried to make her quit. “Coaches would put their best guys on me,” she says. “Three guys, trying to hurt me so I wouldn’t come back.”

As a kid, she didn’t realize the coaches were trying to push her out. “I just thought I needed to get better” to compete with the best, she says. “But my mom saw what was going on, and she called another gym. They said, ‘We don’t train girls.’ It was hard for them to believe that a girl could do what a guy could do. It’s a macho, manly man sport.”

But the struggle just strengthened her drive. Wrestling gave her confidence in a way that other sports she had tried—swimming, ballet—did not. “I knew from age eight that I wanted to be an Olympic champion,” she says, even though women’s wrestling was not yet an Olympic sport. “That resolve shaped a lot of my decisions.”

She finally got a shot when her mom approached a coach from the “no girls” gym at a tournament. The coach saw Maroulis in action there and invited her to train at his gym, defying his fellow coaches. Maroulis joined the gym and continued to wrestle against boys, growing ever stronger. The boys didn’t seem to mind training with her, for the most part, she says, recalling that many of them didn’t share her lofty career goals. “A lot of the kids said, ‘My dad’s making me do this,’ ” she says. “But I really loved it.”

In 2004, when she was 13, women’s wrestling became an Olympic sport. That year, she had an opportunity to see the first U.S. women’s team train in person at an Olympic training center—further fueling her passion. Finally, “I could see people that looked like me,” she says. “They were tough as nails, and so dedicated.”

Her parents cheered her on. For her father, the sport was personal. When he first came to America as a child, the other kids bullied him for being an immigrant. “They said, ‘Look at the imports!’” he says. “My friends looked the other way, but not me—I had to say something back.” Fights ensued, and in high school, he took up wrestling to defend himself. He ended up loving the sport. “I really got into it,” he says. “The confidence wrestling gives you is incredible.” He went on to wrestle at community college for two years, before launching his own business as a government contractor. Later, his two sons and daughter all took up the sport, but his daughter is the one who ran with it.

In high school, Maroulis joined the boys’ team since there was no team for girls, facing more obstacles. For one, she says, a top wrestler on the team refused to train with her because his girlfriend didn’t think it was appropriate for him to wrestle with a girl. Nonetheless, Maroulis excelled, becoming the first woman to place at the Maryland state wrestling championships as a freshman in 2006. “She was like a little spitfire,” her father recalls. “She was not afraid.” He remembers how “the whole arena erupted” in cheers when she defeated her burly male opponents. “She was one of the pioneers in wrestling for women.”

Other high school teams noticed her success—and refused to compete with her. “My sophomore year, everyone forfeited against me,” Maroulis says of the other teams. “They didn’t want their guys to lose to me.” She just grew stronger. “I wouldn’t want that experience for any girl, for sure, but I used that experience to help shape me,” she says. “Those were challenges that primed me.”

She looked for colleges with women’s wrestling teams, competing first as a student at Missouri Baptist University and later at Simon Fraser University in Canada. In 2011, she won a gold medal at the Pan American Games in Guadalajara, Mexico, continuing a long-running win streak that made her a top contender for the 2012 U.S. Olympic team. Her dedication was about to pay off.

And then, a devastating blow: She failed to make the team, losing in an achingly close final. The loss was crushing. “Wrestling was my identity,” Maroulis says. “It determined my self-worth.” On top of that, the coaches asked her to serve as a training partner for the woman who defeated her, Kelsey Campbell, to help her prepare for the Games.

Having come so close to her dream, only to be asked to help train the person who beat her, left her feeling “broken,” she says. “That was just such a test of my character, which I totally failed.” Then a coach told her, You will get there. And what you do now as the No. 2 will be remembered a lot more than what you do as the No. 1. “It got me out of my funk. It became a defining moment for me.”

She trained hard with Campbell and traveled to the 2012 Olympics in London, gaining perspective on her life. “As hard as it was for me, it was equally healing,” she says. “I thought, This is just a sport. Why would I want this sport to define me?” She regrouped and set her sights on the 2016 Games.

Over the next four years, Maroulis trained diligently and stuck to a strict diet—mostly chicken and spinach—to shed pounds to make the 53-kilogram Olympic weight class, because her prior weight, 55 kilograms, wasn’t an Olympic class. “It was a 24-7, seven-day-a-week job, eating the same stuff every day and grinding it out,” she says. Finally, it all paid off. In 2015, she won the world championship in Las Vegas. And in 2016, she achieved her dream, making the U.S. Olympic team.

At the Games that year in Rio de Janeiro, she marched forward into the gold-medal showdown. Her final opponent: Saori Yoshida of Japan, an imposing three-time defending Olympic champion who had won 13 consecutive world titles. Maroulis had performed well in the lead-up to the match, even thinking at one point, “I’m going to win the Olympics.” But minutes before the match with Yoshida, doubts snuck in. “I’m thinking, silver is good enough. Then I said: No, Helen. Go for it.”

She did, ending Yoshida’s incredible streak to become the first female wrestler in the U.S. to take home an Olympic gold medal. “To beat a legend, that was one of the best days of my life,” she says. “You can’t really replicate that.”

After her win, she went to visit her father’s childhood island of Kalamos in Greece. Her dad watched her arrival on video, emotions soaring. “Everyone on the island, all the people came down cheering her as the boat came in,” he says. “Church bells were ringing, horns honking.” To see his daughter return to his homeland as an Olympic gold medalist filled him with pride. “I left this island when I was a little boy, when there was no electricity or running water on the island,” he says, recalling how he had to learn a whole new world when he came to America, including learning to speak English. “And here comes my daughter, back to the island where I was born.” Later, the Greek government honored her by putting her image on a postage stamp. Says her father, “They really love her there.”

***

In 2017, Maroulis was at the top of her game. On the heels of her historic Olympic win, she dominated at the world championship in Paris, preventing her opponents from scoring a single point against her as she captured her second world title. Then, in 2018, came the crash of the concussions and the diagnosis of PTSD.

Upon hearing the diagnosis, she headed to a treatment center specializing in trauma. There, as part of her therapy, she was asked to describe her experience time and again. “They wanted me to keep retelling the story of what happened to me; I was reliving it,” she says, which was painful and frustrating. At first, she wanted to blame people for what had happened to her, but she learned to move forward from those feelings and focus on healing. “They helped me work through it,” she says. “It really opened my eyes to trauma. As strong as our brains are, sometimes they’re really fragile. At the end of the day, we’re human.”

It’s common for athletes to experience PTSD from injuries, says Shari Botwin, a New Jersey–based therapist and the author of Thriving After Trauma. “Elite athletes have additional pressures because of the expectations of their coaches, fans, sponsors and sometimes their families,” she says. “They are taught from an early age to be tough, wipe it off and keep competing. From the moment the injury happens, many athletes’ lives are turned upside down. Their identity and role in their sport feels taken. Coping with trauma is more difficult when there is expectation and pressure from the world around them to be tough; at times, athletes give into the pressure and return to their sport before they are healed.”

After attending the treatment center, Maroulis considered taking a year off and spending it with family on the quiet island of Kalamos. But she decided to compete at the 2018 world championship in Budapest instead, thinking that if she didn’t, she would never wrestle again. In retrospect, she says, it was premature. She ended up seriously injuring a shoulder in a first-round match. It became another crucial turning point in her life.

“Finally I had something on the outside that reflected how broken I was on the inside,” she says. “Finally I had to sit and deal with all this stuff. I realized, you can’t just wrestle your way out of this.”

She continued treatment for PTSD and moved home with her parents in Maryland in December 2019 to give herself the time to rest and heal, turning to dance instead of wrestling. Says her father, “We told her, ‘Come home, you’re going to be with your family. Forget the gold medals. This is about your health. You don’t have to prove anything.’”

Maroulis credits her family, and her faith in God, with helping her find a path toward healing. “I realized it wasn’t about pushing through; it was about letting go,” she says. “You have to let go of everything and let yourself heal.”

Botwin says this realization is key to recovery. “When you realize you need to stop and acknowledge the physical and emotional ramifications of your injury, you begin the process of healing from PTSD,” she says. “Wrestling through pain without understanding it or learning how to cope with it inevitably leads to more years of trauma. Helen’s story is so important because she is modeling the importance of sitting with her emotions as part of her healing.”

Once Maroulis allowed herself the time and space to heal, she realized she wasn’t done with wrestling just yet—she didn’t want to regret leaving the sport before she felt truly ready. And so, she returned to competition this past February and won a wrestle-off to go to the Pan American Olympic Qualifier in March. There, she won all her matches and qualified the weight class for the Olympics. She is now headed for the finals of the U.S. Olympic Team Trials, which have been postponed, along with the Games, until next year amid the coronavirus.

“I train differently now. It’s always about my health,” she says. “There are certain things I will never push through. Most people think about what they need to do in training to be ready for competition, but I focus on how my body feels and how I can stay healthy.”

She emphasizes that she is sharing her personal story because she wants young athletes to know that they are not alone in the battles they face, and that their health and well-being are paramount. “At the end of the day, sport is about learning to grow as an individual, developing your character,” she says. “It’s not about feeling you must do whatever it takes to get a medal.”

She says her many hard-won battles over the years have strengthened and prepared her like never before. “I love wrestling and I feel better now than ever,” she says. She adds that there are still battles to be fought—namely, the ongoing quest for respect and equality for women in the male-dominated sport. To be sure, she will be at the forefront.

As for the delay in the Olympic Games, she is unfazed. “I don’t fear time,” she says. “I’ve had my dreams delayed before.”