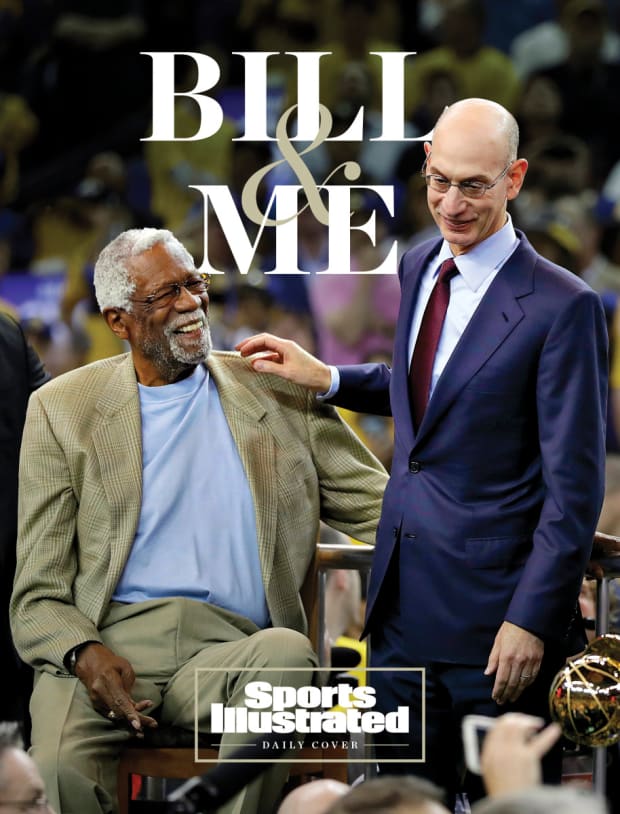

To Adam Silver, Bill Russell was more than just the game’s greatest champion. He was also a close confidant and friend.

Long before he was running the NBA, Adam Silver was an eager young staffer whose duties included opening mail, writing memos and carrying around large stacks of glossy Bill Russell photos—all of it important, none of it as gratifying as the last bit.

Russell, of course, was famously reluctant to sign autographs, preferring a conversation or a handshake to a scribbled signature as a means to connect with people. But for the fan who required something tangible, there were the glossy photos. And Silver, in his role as special assistant to the commissioner in the early 1990s, had the job of navigating those moments.

“I would cringe each time,” Silver recalls with a slight chuckle, “because there were a few generations of fans who didn’t know that Bill Russell did not sign autographs and seemingly would naively say, ‘Mr. Russell, can I get your autograph?’ And I would almost be holding him back, and I’d be jumping in, ‘Uh, no.’”

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

Invariably, sometimes brusquely, Russell would decline. And then young Adam Silver would jump in: “But here’s a picture of Mr. Russell!” Silver, now the NBA commissioner, laughs warmly at the memory.

Russell, who died on July 31, at age 88, was buried last week in a private ceremony in Seattle. Silver gave a eulogy. To the basketball world, Russell was a towering icon—its greatest winner, its greatest champion and its fiercest advocate for civil rights. To Silver, Russell was all of that, certainly, but also a close and trusted friend, a confidant and a sounding board, going back to those days traveling the country in the early 1990s, when the two spent countless hours together.

“I was so green and eager to hear his stories, because he was one of the all-time great storytellers,” Silver says. “He had a profound influence on me.”

It’s common for commissioners in each of the major sports leagues to mingle with the living legends of their games, at Hall of Fame ceremonies and All-Star Games, and perhaps even to seek their counsel. But it’s rare that those moments beget a true friendship—or as Silver calls his bond with Russell, “a special relationship” that transcends the duties of the job.

That’s what evolved over the last three decades, as Silver rose from special assistant to commissioner David Stern’s chief of staff, to president of NBA Entertainment, to deputy commissioner and finally to his current role in 2014. They shared long flights and limo rides, took in All-Star Games and Finals together, and spoke frequently by phone or text.

“He was really part of my life—for the last big part of my life, for the last 30 years—and just a really unique person in the world,” Silver, now 60, says of Russell.

Silver often sought Russell’s counsel on major issues, especially when the league was confronted with challenges that went beyond the court. Silver immediately says “yes,” when asked whether there were specific moments when Russell’s voice was key, though he prefers not to divulge the details.

“I’ll just say to you that on important issues involving the league, particularly about race, I generally consulted with Bill,” Silver says.

Silver often referred to Russell as the NBA’s Babe Ruth, except—because of the NBA’s relative youth as a league—this Babe Ruth still walked among his modern-day descendants, providing a wealth of perspective and advice. Russell’s unparalleled success—11 championships with the Celtics and five MVP awards—made him one of the sport’s most revered legends. His unwavering activism in the 1960s, in the face of an often extreme backlash, made him one of the most admired, and a role model for today’s stars.

“He’s sort of the founding father of the modern NBA,” Silver says. “And with that I think he became the league’s DNA for our players to feel comfortable speaking out on societal issues. I would say a lot of the courage of the modern-day players, there's a direct through line to Bill, against the whole shut up-and-dribble crowd.”

When the NFL’s Colin Kaepernick and other players were vilified for kneeling during the national anthem as a protest against police brutality, Russell backed them on Twitter—with a photo of himself on one knee. In August 2020, when NBA players staged a wildcat strike in the wake of the Jacob Blake shooting in Kenosha, Wis., Russell offered both support and perspective via another Twitter message: “In 61, I walked out of an exhibition game much like the NBA players did yesterday. I am one of the few people that knows what it felt like to make such an important decision.”

As Silver notes, Russell attached an old newspaper clip, headlined, “Russell Would Give Up Basketball for Rights,” which included a much more nuanced quote from Russell—that he would sit out only if he truly believed it would make an impact.

“He recognized the value of the platform that was afforded him by being an MVP, NBA champion player,” Silver says. “And he was realistic about that. … He ultimately decided, obviously, he could do more through the platform that playing offered him. But he tweeted that clearly in support of these players, saying that, ‘I have your back.’ And again, classic Bill, he wasn't saying that means you shouldn't be playing—because he kept playing—but it was just saying, ‘I understand. That’s something you all should be thinking about.’”

It’s fair to say that Silver, too, internalized those lessons through his long talks with Russell over the years. There’s a little bit of Russell in Silver’s executive style, too, particularly the collaborative approach Silver takes with his various constituencies. Russell often used the analogy of a “three-legged stool,” in which players, owners and fans are the three legs propping up the seat, “and how important it was that each one of those elements be cared for in order for the league to remain strong,” Silver says. It was a theme Russell repeated often as Silver prepared for his ascension to commissioner in 2014.

“Clearly, he thought relations with players from the league office were critically important, but it wasn’t players above [the league],” Silver says. “He recognized also without team owners, we wouldn’t have a league. But also without fans, we wouldn’t have a league. And constantly reminding me to care for all three groups.”

Famously diplomatic as an executive, Silver says he admired Russell’s unfailing directness and candor (“if anything, I could use more of,” Silver says), a willingness to speak his mind without worrying about the consequences or what people thought of him.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

Over the years, Silver delighted in seeing younger players meet Russell, hear his stories and soak in his experiences—about championships and personal sacrifice, about the formation of the players association, about the challenges of being a Black athlete in his era, about his decision to speak out.

“Bill took it on himself, for those players that were interested, to seemingly have an unlimited amount of time to tell them what it was like in the early days of the league,” Silver says. “There was never any bitterness. It was never this notion, ‘If I made the money you guys did today’ or ‘You guys have it easier than I did.’ Never, ever. It was more, ‘This was my experience. This is how I experienced the league.’”

As for those autograph requests from hopeful fans over the years? Well, Silver says, Russell occasionally signed one. But his reluctance was never a sign of disdain or indifference. As Silver explains, Russell preferred a true interaction, a conversation. He would ask, “How are you?” And when the person responded, Russell would start asking follow-up questions.

“So he was happy to engage with people,” Silver says. “It was just that to him, there was nothing more superficial than his signature on a piece of paper, as opposed to a conversation with him.”

“To him, supporting the fans meant a lot more than signing autographs,” Silver adds. “It meant professionalism. It meant how players approached the game. It meant players’ willingness to play as a team, to give their all in pursuit of winning. That’s what I think he meant by what they owed the fans.”

Silver was thrilled when in 2009 Stern named the Finals MVP trophy in Russell’s honor, not just because of the gesture, but because it meant Russell would be present each June at the Finals, another chance to reconnect with his friend. In the instances when Russell wasn’t feeling well enough to watch courtside, Silver would often spend part of the game with him in a back-of-house room, watching on TV. “And it was fun just to tell stories,” Silver says. “He remained in good humor.”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

The June tradition mostly held until this year, when health concerns kept Russell from attending the Warriors’ closeout game in Boston—although Silver says Russell would have made it to a potential Game 7 in San Francisco, given the shorter flight from his Seattle home.

At the funeral last week, Silver revealed to the gathered friends and family members that Russell’s No. 6 would be retired leaguewide, a first for the NBA. “I thought that seemed like the perfect opportunity to do that, tell his family first and his close friends,” he says.

In the years ahead, Silver will surely keep drawing on the friendship, on the wisdom and the lessons Russell generously offered, the example he set. It’s too early yet for Silver to pass along those lessons to his two daughters (ages 5 and 2), but there will be no shortage of words when the time comes.

He’ll tell them Russell was someone who truly lived in the moment, who was never in a hurry, who in the midst of that conversation—with the adoring fan or the curious young athlete or the NBA executive—was firmly focused on the personal connection, a skill that seems all the more vital in an age of multitasking and distraction.

“Bill was doing one thing at that moment: He was talking to you. And if I could teach my daughters that skill …” Silver says.

Eventually, of course, he’ll also tell them about the basketball, about all those banners, and how Daddy’s friend Bill became one of the greatest champions of all time.

“For whatever my children want to do in their lives, it may have nothing to do with sports, or it may not be something which traditionally you think of as a competition where people get objectively ranked,” Silver says, “but I’d want to teach them that quality of truly being willing to give your all to what you’re passionate about. And that’s the unique quality that Bill had.”

• What Does It Mean to Win at Saving Lives?

• She Kicked for Vanderbilt, and Then Things Got Hard

• ‘A League of Their Own’ Endures Because It’s Personal