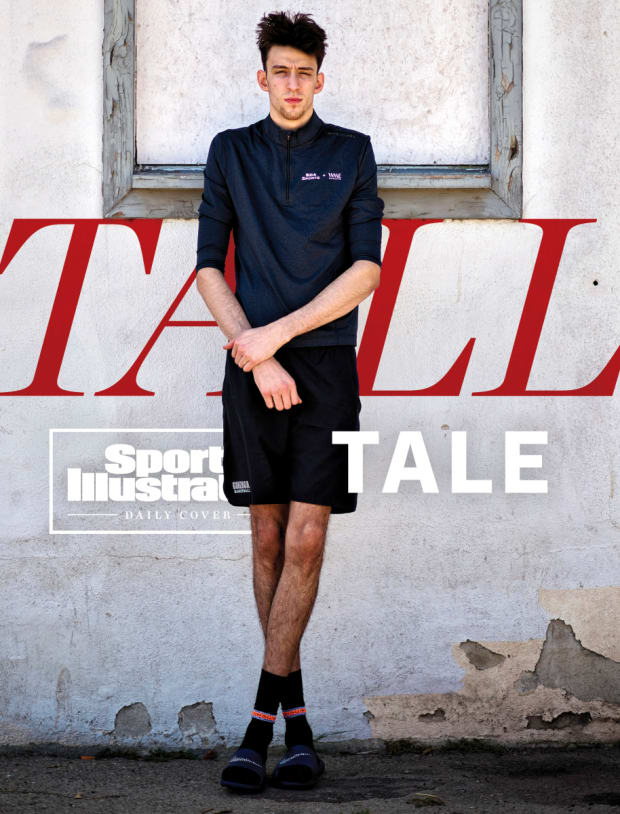

It all depends on whether this surefire lottery pick’s 7’ 1”, 195-pound frame can hold up in the NBA.

Down an unmarked side road, inside a nondescript gym with adjoining basketball courts, the most remarkable draft prospect in NBA history is raining threes in an unremarkable setting. Local advertisements—organic ice cream, discount car washes, Blender’s basketball league—hang from the walls. His father trains a camcorder on the court. Women tow yoga mats inside.

Sweat drips down Chet Holmgren’s much-discussed frame, soaking his T-shirt for emphasis. He’s toiling to realize his evolutionary promise, make sense of what he cannot fully explain and solve a problem that may not, in fact, be one. But he is not priming for the NBA draft alone.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

On the other court, there’s another is-this-really-happening scene in an is-this-really-happening life. Holmgren hardly notices the women bending and bouncing, clad in stretch pants and armed with foam rollers, as they warm up for a workout of their own. Their teacher, a peppy instructor wearing a headset that blares her instructions over a pair of speakers, stands atop a stage and orders, March it out. Techno thumps. Legs churn.

Jazzercise class begins.

Holmgren continues hoisting jumpers while running, twisting, drifting and shifting. The women feel the rhythm! Holmgren hears splash, splash, splash. When he misses, which is rarely, he bangs his fists together or drops a f---, bro! in frustration.

The scene is revealing, on near and far horizons, in distinct and contrasting ways. It’s impossible to watch Holmgren and not be transfixed by his size (7' 1"), his elegant fluidity (think: ballerina who blocks shots) and the physics he defies from the combination of both. Holmgren once drove around Steph Curry at a camp, while still in high school, if that helps.

Unicorn is an overused sports cliché. But it applies here, in mid-May in Santa Barbara, Calif., the NBA draft looming in six weeks. To study a true unicorn up close, to observe Holmgren slide and duck into positions most centers wouldn’t dare attempt, is entrancing and forward-pointing. Because he just turned 20. Because he’s already good. And because of what he can be: the next step in an ongoing, leaguewide transformation.

The other reveal is just as obvious and more fiercely debated. When Holmgren removes the dripping shirt, it’s possible to clearly delineate each individual rib and those twig arms on his skeletal frame.

That’s the crux of his “problem” and the equation he must solve in the weeks and years ahead. Will Holmgren seize on all that makes him unusual? Or will he falter, because of that bookmark-thin body, whether from injury or getting knocked around like the world’s tallest pinball?

After taking almost 600 shots, while Jazzercise class intensifies, an app on his iPad sends him statistics for the workout. He checks the data—in the paint (77%), midrange (68%), beyond the arc (67%). A little low, he muses. His overall benchmark for sessions is 70%.

He dons a virtual-reality headset and sits in a chair. Sequences borrowed from recent NBA playoff games unspool, only he’s there, reacting, picking correct options. “That guy left the space open. Go right at him and boom,” he tells a trainer, mimicking a seated windmill dunk.

The goal with all this is to marry both sides of his brain, by deploying a pragmatic approach to an endeavor that is inherently creative. All so a pro prospect long tabbed for stardom, one-and-done at Gonzaga, can transform from a future NBA star into an actual one. “Yeah,” Mr. Unicorn says, his nonchalance warranted and striking. “I see myself in this new era, new style of basketball, where guys can do everything. And it’s not just wanting to go for it. I feel I can do everything, or get to that point, on offense and defense.”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

An hour later, a few miles away, Holmgren begins his other daily workout alongside prospects (Jermaine Samuels, E.J. Liddell), a volleyball star (Kim Yeon-koung) and his comedic foil, Tacko Fall, the 7' 6" center. Fall refers to Holmgren as “Tiny”; Holmgren responds with “Short Stuff.” Their relationship is ripe for a sitcom: Towering Comics Who Can Dunk Without Jumping.

When Holmgren skips rope to warm up, he recalls a boxer’s grace. (At 195 pounds, he’d be the world’s tallest cruiserweight.) He moves on to ladder hops, then standing jumps, where he starts on a box, hops down and leaps atop a training table. Easy, smooth.

His trainers at this peak performance laboratory, P3, tout their focus as the intersection of sports and science. They study how basketball players move: hunting for weaknesses, imbalances and anything that portends future injury. And their data has projected NBA futures with staggering accuracy.

In the last 10 years, P3 has trained eight No. 1 picks. What separates true superstars from mere mortals, according to gym founder Dr. Marcus Elliott, is “something physical, some sort of movement system, that gives them a competitive advantage.” Lateral speed and horizontal force separated 2020 top pick Anthony Edwards

from every other prospect, foreshadowing his early success that surprised some. Elliott argues that such disbelief highlights a flawed evaluation system. Scouts know how to identify young talent, because it’s obvious. Start with the bouncy kids, the ones who can jam in sixth grade. Study their careers. Then fall back on what he calls “a historical paradigm.” This guy is like that guy, and that’s how we’ll make sense of him.

Elliott is looking for outliers, anything that makes a prospect “special.” Few evaluators study how those same springy players interact with the ground. Fewer still teach them how to land. Or explain to them why their knees hurt. Or apply data to gut instincts to build out those systems that separate the superstars. Teams embrace places like P3 a little more each year, but progress remains slow, despite how much the NBA continues changing.

P3’s studies show commonalities between elite players. They use a jargon-heavy process called principal component analysis to compile data sets from a player’s movement. The data reveals patterns that inform how individual movements combine for overall athleticism, from smooth on down to sputtering.

Elliott is most interested in athletes whose numbers place them in a group he calls “kinematic movers.” They’re typically not flashy in how they jump or run. Many—Trae Young, C.J. McCollum, Edwards—are doubted, because there’s no obvious superpower to hold up and compare.

Instead, kinematic movers elevate with a totality of movement, every jab step and sideways leap and spin move tying together. They don’t have “asymmetries,” or imbalances, meaning they’re less likely to get hurt. They present fewer attackable weaknesses because of elite equilibriums. “They’re movement experts,” Elliott says.

Holmgren’s early test results backed up his nickname. Super rare, Elliott says, unlike anyone we’ve ever had. They suggest not only NBA success but also career longevity. That’s no, um, small thing at his height. Most players who stand at least 6' 10" register unpredictable patterns, because their systems are longer; there’s more to connect. Should Holmgren move into the kinematic-mover cluster, which Elliott predicts will happen, he would morph into something else, something bigger: a player unlike any other in NBA history.

The next step in this basketball evolution.

Darren Yamashita/USA TODAY Sports

Inside an office on that day in Santa Barbara, The Unicorn leans back. He’s momentarily silent, trying to remember the first time someone compared him to a mythical animal, horn and all. He thinks it started on Twitter and knows it spread instantly. He only wishes he had looked into trademarks, or at least slapped CHUNCRN on a personalized license plate. And, while he would never describe himself that way, the moniker doesn’t bother him. Over time, he even came to understand the premise.

“It doesn’t make sense to me, either,” he says. “Why I’m 7 feet tall and I have this coordination that people haven’t really seen before.”

Perhaps the ensuing laugh stems from the real weight of all this, the projections and the skinny-player problems and the parallels to an animal that’s as real as Santa Claus. The path to an implausible existence began not with a single confident step but several painful (and awkward) ones. While growing up in suburban Minneapolis, baby Chet managed to climb out of his crib and fall backward, his shenanigans announced with a thud. In elementary school, he tried various sports, even moonlighting briefly as a linebacker/tight end to improve his coordination.

By middle school, a growth spurt had inflamed tendinitis in both knees. Physical therapists introduced Holmgren to the concept of movement patterns and how to bolster them. His pain vanished. Point made.

If Holmgren is skinny now, he was whatever is less-than-skinny then. He couldn’t do five push-ups without dropping his knees to the ground, couldn’t bench-press his body weight and couldn’t perform a single pull-up. But his childhood coincided with that NBA trend. He noticed it in Tracy McGrady, a 6' 8" swingman who towered over defenders on the perimeter and blew by them for easy buckets, a precursor to the versatile big men who would move out from under the basket and show off their perimeter skills.

Enter Larry Suggs, a local AAU coach. A friend pointed Suggs toward the tall kid, but height alone didn’t pique his interest. This tall kid could scale trees and jump onto his roof, signaling two critical traits: fearlessness and body control.

Suggs had already developed his own philosophy, teaching a European style of positionless—or multiple position—basketball and adding isolation moves popular in the 1980s to further diversify skill sets. He hated how other coaches just shoved tall kids into the paint. He taught Holmgren the same way he schooled his son, Jalen, who stopped growing at 6' 5", then starred at Gonzaga and was drafted fifth by the Magic last year. “I showed them pro moves in a little kid’s body,” Larry says.

Counterparts all but laughed Suggs out of the gym. He continued drilling the boys with footwork exercises, spacing concepts and agility training. Holmgren continued growing but retained the soul of basketball’s tallest point guard. He was Suggs’s proof of concept, part savant, part fast learner, all unicorn. The teen spied foreign concepts on television, or learned new maneuvers from his coaches, and applied them the same afternoon. Movement set up everything else, from crossovers that wobbled defenders to leaps timed to swat shots into the stands. “A lot of times, playing pickup, stuff I’ve never worked on just kind of happens,” Holmgren says, “just kind of comes to me.”

At an AAU tournament, Suggs watched Holmgren block a shot, grab the ball, dribble and pull up for a three-pointer. Suggs glanced at Kentucky coach John Calipari. “Did I just see that?” Calipari mouthed. Suggs nodded. Stakes, raised. “I wanted to make Chet the best American-born white basketball player since Larry Bird,” Suggs says.

Holmgren’s systematic development only broadened the creative flair that made him unicorn adjacent. With Jalen, he led Minnehaha Academy to state titles in 2019 and ’20. With Larry, he helped turn the awesomely named AAU outfit—Grassroots Sizzle—into a force. The success, in turn, morphed Holmgren from tall and awkward into the nation’s top recruit.

Every step in his evolution mirrored how the NBA was shifting, away from the specialists—the shot blockers, defensive stoppers and long-distance marksmen. This heightened already lofty comparisons, like to a certain future Hall of Famer who roamed outside, drilled triples and stood 6' 10". Yes, basketball experts watched Holmgren and saw . . . Kevin Durant.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Sometimes, when Elliott hears endless debates over what he refers to as the weight-versus-resiliency equation, he wonders why “outlier” equates to “problem.” The same bloviators who say a 300-pound center is too heavy to join the legion of NBA leapers now collapse in concern over a 195-pound post who, they insist, can’t be that skinny and survive.

Elliott believes those fears stem from the unknown. The subconscious is a mystical place, transmitting “that can’t be right” when eyes see what they have never before witnessed. There’s no real understanding; the brain simply cannot comprehend something like . . . a unicorn.

While some view Holmgren as a potential bust, and others insist he must add 40 pounds to a frame that threatens to disappear when he turns sideways, Elliott turns instead to the same place: objective data and relevant comparisons. Both show that Holmgren is less likely to suffer a serious injury by running into a human brick wall than if he carries too much weight. Strength and size do matter. But not as much as his wingspan (7' 6") or his movement efficiency.

On Holmgren’s first day inside the performance center, P3 hooked 22 tiny circular sensors all over him. When he jumped, force plates in the floor turned the feed into data points that measured his coordinated movement—right shin to right knee to right hip—and how one movement led/tied to the next. The results (quite well) formed a better baseline than anticipated. “Typically, our models don’t like big guys,” says Eric Leidersdorf, P3’s director of biomechanics. But they loved Holmgren.

One measure: A typical NBA post player averages between 24 and 25 inches for a standing vertical jump. Holmgren, without any P3 training, leaped 27, which already ranks among the top 10% of NBA high jumpers.

Another: The risk stratification model—convoluted science speak for $1,000, Alex!—produced a 3-D model of The Unicorn’s frame. On a laptop screen, there’s Holmgren in bionic form, with circles placed on his digital body. Red ones indicate injury red flags. He has none, in what Leidersdorf calls a “clean profile” that predicts a long career with few missed games.

Holmgren’s baseline so blew his trainers’ minds that they considered (not really) sending Gonzaga’s staff a gift basket. They polished Suggs’s creation, adding weight but naturally, so he wouldn’t slow down. Holmgren studied film of NBA workouts, hunting for new movements while embracing mental training—sessions every Monday on personal growth, meditation and sleep scheduling—that helped him move even more freely.

He didn’t wow teammates with any one thing but with how he did everything well. On defense, he protected the rim like a one-man Secret Service detail. It was one thing, at his height, to block shots and intimidate scorers away from closer attempts. It was more impactful for him to leap, soar, absorb contact, contort and block shots to waiting teammates for easy transition buckets. Sometimes, he even shadowed guards on the perimeter, serving as the rare post who blew up every variation of the pick-and-roll.

At Gonzaga, Holmgren’s presence alone opened space, as did his range (39% from deep, 61% overall). He could pass with aplomb and showcased surprisingly nimble hands. His coordination powered his progression. Despite playing only 26.9 minutes per game, Holmgren averaged 14.1 points, 9.9 rebounds and 3.7 blocks. Efficiency models fell in love. He was the nation’s best rim finisher (PPP) with 100-plus possessions (1.64). His win shares per 40 minutes was .294, fourth in the nation.

Since the 1992–93 season, a player has posted higher averages for points, rebounds and blocks 51 times, according to Basketball Reference. Think: Tim Duncan, Emeka Okafor, Greg Oden. With the exception of maybe Duncan, Holmgren is a much better mover—and Duncan bricked four of five long-range attempts.

Put everything together and that’s the top of his projection: a game so versatile and impactful not just on offense but also defense that it’s hard to conceive.

“Evolutionary player is a fair target,” Elliott says.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Anyone expecting Holmgren to wave off talk of his potential that’s now taller than he is or beg for new brakes on the hype train will be surprised. He does not. He’s not actively pushing anything. But he answers questions honestly, and he honestly believes that someone could stack several Chet Holmgrens atop one another and the highest head still wouldn’t touch his ceiling. “I’d agree with it,” he says, when relayed Elliott’s target. “Where I’m trying to get to is: Take everything that’s been done and add to it.”

He’s circled back to the Durant comparison, pushed by a theory. It’s unlikely that he’ll ever shoot or score like KD, and yet, he believes he will shoot, he will score and he will protect the rim, block shots and swallow space like Durant never will. Holmgren won’t have a taller player behind him. He won’t need one.

Holmgren is asked what he means, for specifics on what’s possible. He starts to answer and stops, before deciding not to go too far. He’d rather show than tell. He says, instead, “It comes down to what position you’re put in.”

There’s the other crux of this experiment—right team, right situation—and it’s entirely beyond Holmgren’s go-go-gadget reach. He can dive into the science, everything new, the “sports world controlled by a bunch of geeks—and it’s awesome.” He can shore up his minor deficiencies: how his feet interact with the ground as he moves and cuts; his ability to absorb load from landing and cutting with his hips, which would save his knees later in his career; and his lateral drive, which would allow him to better cover space in perimeter defense, such as when he’s guarding pick-and-rolls. He can add pounds without losing fluidity; offset weight deficits with agility, lateral speed, angles, elbows and elite change of direction; and become even more creative, the tallest kinematic mover in the NBA.

“We’ve accepted that Steph Curry can be small and not ridiculous in terms of jumping ability and still have an amazing career, right?” Elliott says.

What Holmgren cannot do is convince whichever team might draft him to follow the same strategy. To focus on what makes him The Unicorn, not what makes him the world’s skinniest mythical beast.

For the four likeliest options—Holmgren, Jabari Smith (Auburn), Paolo Banchero (Duke) or Jaden Ivey (Purdue)—expected to be drafted first, no one disputes that the

tallest and skinniest prospect also holds the most potential. The doubts that flutter around him are reminiscent of Luka Dončić in 2018. Dončić wasn’t athletic enough, supposedly, which shifted focus away from his strengths. Elliott offers a science lesson as a warning. “Basketball,” he says, “is movement.”

Best case: Holmgren becomes like Durant, only with a greater defensive impact. Similarly built centers roam NBA courts like guards. The evolution of versatile basketball becomes taller and even more varied.

Holmgren already has better “defensive instincts” than any of the taller players draining threes on the NBA perimeters, according to Packie Turner, his basketball trainer. Turner believes Holmgren would “make for a hell of a pro” if he stood only 6' 6".

Worst case: Someone knocks Holmgren into reality, breaking a really long board in half.

Either way, there’s no precedent, and that’s why Holmgren inspires awe and fear. When those are the stakes, it’s easy to forget he’s only 20. He returned to Gonzaga in early May, taking final exams in legal ethics in sports, business computing, freshman English and sports finance. He devotes his free time to video games. He might own a razor but doesn’t need one.

“They call me The Unicorn now,” he says. “But it won’t matter.”

Perhaps this signals maturity or a grasp on his most important class, the basketball-science seminar at P3. He’s right, regardless. Because in the grand basketball experiment that is his future, at some point, potential will no longer matter. Unless, that is, he realizes it.

More SI Daily Cover Stories:

• In Ukraine: ‘Every Victory, Sports or Otherwise, Aids Us’

• The Classified Case of the Pro Wrestler Who Helped Beat the Nazis

• Should Russian Athletes Be Allowed to Compete?