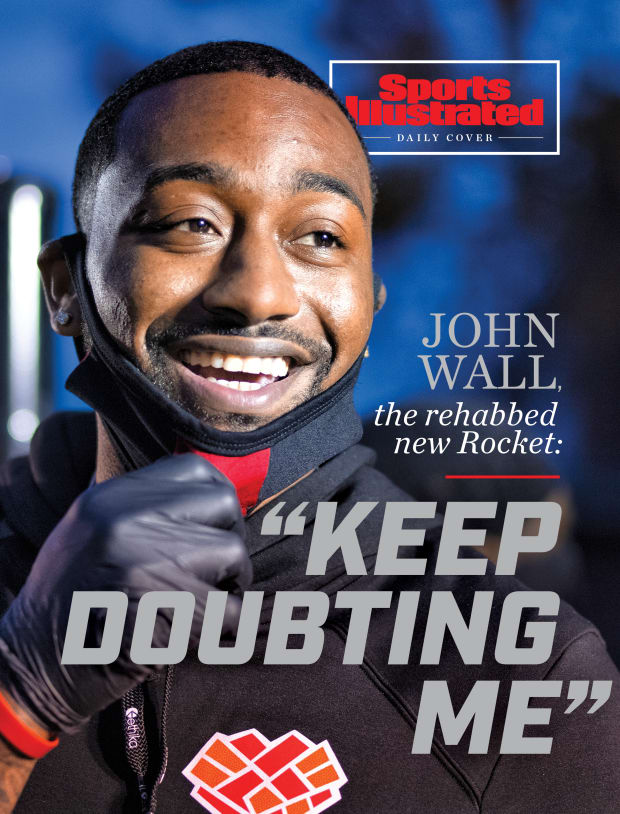

Injuries have kept him off the court for the last two seasons, but Wall says he’s healed and better than ever. In Houston, he’ll have a chance to prove it.

The shrill sound of squeaking sneakers cut through the air inside a Thousand Oaks, Calif., gym, a soundtrack to one of the best pickup games played anywhere this year. It’s mid-October, days after the end of the NBA’s pandemic-interrupted season, a month and a half before the blockbuster trade that would hit days before training camps opened, and in a gym that until recently bore Kobe Bryant’s nickname—the Mamba Sports Academy—a collection of top players are putting in work. Kevin Durant elevates for jump shots. Kyrie Irving spins a dribble toward the rim. DeAndre Jordan and Thomas Bryant battle for rebounds. Troy Brown and Isaiah Thomas, ex-Wizards teammates, trade buckets. Each has good moments. John Wall has more.

In transition, Wall is a blur. Nearly two years have passed since he played an NBA game, his 2018–19 season cut short after 32 games by surgery to remove inch-long bone spurs from his left heel, his ’19–20 campaign stolen by a ruptured Achilles suffered after slipping and falling at home a month later. Speed can suffer after an Achilles injury, and Wall, who ran a 3.14 in the ¾-court sprint at the draft combine and five years ago declared himself the NBA’s fastest player, is defined by it. In this workout, Wall doesn’t appear to have lost a step. The knee pain that preceded the heel injury has vanished, leaving Wall feeling healthier than he has in years. “He looked amazing,” says Durant, who is returning from an Achilles tear of his own. In quieter moments, Wall and Durant commiserated. About being away from the game. About personal growth. “It was a deep convo,” says Durant. “I’m excited to see John play again.”

Indeed, in scrimmages, Wall flashes all the familiar tools. He stops sharply, an unremarkable feat until you consider where he was pre-surgery. That Wall didn’t so much stop but slow, the heel pain so sharp he struggled to dip into a defensive stance. “It felt like somebody stuck a knife in there,” says Wall, “and just kept twisting it every time I took a step.” At night, Wall would walk on his toes to get to the bathroom. There were days Washington coach Scott Brooks wondered whether Wall should be on the floor. But this was Wall, the same player who, after fracturing his left hand in five places in Game 1 of the conference semifinals in 2015, not only finished the game but also returned for the final two with a hand, says Wizards GM Tommy Sheppard, “that looked like Professor Klump’s.”

“When I’m between those lines,” says Wall, “I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do.”

In the pickup game Wall pulls up, releasing a polished jump shot. Perimeter shooting, never Wall’s strength, became a glaring weakness in recent years, with his three-point percentage, which has hovered around 34% during his career, dipping to 30.2% in his last season. Off the ball, teams regularly declined to defend him. With months to kill while his leg healed, Wall, with the help of Wizards assistant Alex McLean, retooled his jumper, shifting his hand placement and raising his follow-through. “People think he will be different,” says McLean. “He’ll be different—he’ll be better.”

Some will buy it. Others won’t. How a player recovers from an Achilles injury is notoriously difficult to predict. Kobe Bryant, then 34, was never the same after his snapped in 2013. Chauncey Billups, either. Wesley Matthews lost some mobility after he tore his in 2015. It’s still up in the air whether DeMarcus Cousins, two years removed from his injury, will ever regain his All-Star form. For a player who depends on speed and quickness, like Wall, the comeback can be more daunting. “We don’t have a whole lot of data on elite NBA point guards with tendon ruptures,” Wizards medical director Wiemi Douoguih said at the time of the injury. “We’ll just have to wait and see.”

Wall shrugs at the skepticism. “I feel like I’m back in high school all over again,” he told Sports Illustrated last month. During the interview, he interrupted a question about his speed. “I don’t feel as fast,” Wall says. “I feel faster.”

So much has been taken away from him. First it was basketball, his passion, the sport that transformed him from teenage hellion to college prospect, from the No. 1 pick to All-NBA guard. Then it was his mother, Frances, Miss Frances to those who knew her, his moral compass, his best friend, who died last December at 58 after a lengthy struggle with breast cancer. His soul will never fully heal but his body has, and Wall is coming to take what he can back.

After a decade in Washington, he will have to do it for a new team. Earlier this month, the Wizards shipped him to the Rockets in exchange for Russell Westbrook. In his introductory press conference in Houston, Wall kept any issues with his former team to himself, despite swirling rumors that he’d told management he was ready to move on. Washington’s public signals during Wall’s long recovery that Bradley Beal would be the face of the franchise had irritated him, sources familiar with his thinking told SI. Still, Wall said at his press conference that he “never thought this would happen. . . . All I can do is embrace it and move forward with life.”

After two years off the court, Wall was already approaching this season as a new chapter in his career; now, thrust into the middle of Houston’s on-the-fly rebuild, it’s a full-on reboot. “You’ve got to think the last, probably six, seven years I’ve been playing through pain, but I don’t make excuses,” Wall says. “People say I’m done, I’m not athletic, I can’t shoot, can’t do all those things. It’s just more fuel to the fire.”

***

In 2013, A 22-year-old John Wall sat at a news conference to formally announce his new contract with the Wizards, with Frances Pulley in the front row. “Words can’t even explain,” Wall said of his mother, his voice trailing off. For decades, Pulley was the lone constant in Wall’s life. His father, John Carroll Wall, died when he was nine, and was incarcerated for most of Wall’s life. Pulley ran things, driving a bus, cleaning hotel rooms, working odd jobs, all to feed the family. Around D.C., she was a familiar figure. “Best sweet tea ever made,” says McLean. Brooks recalls his first encounter, in 2016, shortly after being named Wizards coach. “She told me, ‘You be tough with him—he wants to be coached,’” he says. Sheppard, who, right up until the moment he traded him, had watched Wall’s entire career unfold from his various roles in the Wizards’ front office, has a similar story (all of the Wizards officials talked to SI before the trade). To Wall, his mother was a confidant. Her phone rang four or five times a day, often in the early-morning hours. “He’d just want to talk,” says Wall’s sister, Tanya Pulley. “He was a real mama’s boy.”

Wall’s injury left him homebound throughout 2019, and he cherished the extra time with his mother. “It was a blessing in disguise,” says Wall. Pulley traveled to D.C. regularly, in part to see Wall’s infant son, Ace, in part for chemotherapy. “I went with her a few times,” says Wall. “But I couldn’t see that s---.” In turn, Wall made frequent trips to North Carolina, spending evenings with his mother, glued to whatever games were on, two or three TVs going at once. “If John was home, basketball was on,” says Tanya. Hope for recovery would flicker. “There were days when it was like, ‘O.K., she’s beaten it,’ only to slowly but surely see it fade away,” says Wall. “And then you could see certain days, how it was eating away, eating at her. If you know my mom, she’s getting up every morning at five o’clock going to the T.J. Maxx, Ross’s, flea markets. But her bones got too weak for her to walk. That was probably the most difficult thing to go through, to see her in that way.” Pulley died in a Raleigh hospital on Dec. 12, 2019, with her children by her bedside. Belying the rumored friction between them, Beal, Wall’s backcourt mate with the Wizards, was down the hall, alongside McLean.

Basketball, says Wall, “was my escape route.” But the road back would be difficult. For six months after his second surgery, Wall was in a walking boot. “I couldn’t put my heel down,” he says. “I had to learn how to move my feet, how to move my toes again.” Unable to play, Wall immersed himself in film. McLean stopped by daily to dissect footage. Preferred tape was Washington’s second-round series against Boston, in 2017, which the Wizards dropped in seven games. Says McLean, “We probably watched that series 20 times over.”

Wall bonded with McLean, in part because of shared experience. In 2012, McLean, then playing professionally in Europe, tore his left Achilles tendon. Three years later, he tore the right. “I know what he’s feeling,” says McLean. “I know what it’s like to get your Achilles scraped during rehab. I remember not being able to walk down the stairs. We swapped stories. We compared scars.”

McLean told Wall: I didn’t lose anything. You won’t either. The rehab was tedious. “You had to check the boxes,” says McLean. Wall shed the boot in the summer of 2019. He started shooting. First, flat-footed. Then on his toes. Jogging was next. Then jumping. Wall’s always been somewhat ambidextrous. Right-handed, Wall exclusively dunks with his left, generating power from his right leg. “My right foot has bounce,” says Wall. “My left doesn’t.” Last November, Wall attempted to dunk. He lifted off the right leg. Easy. Then he flushed one off the left. “That was huge,” says McLean. “He [celebrated] like a little kid at Christmas.”

As Wall rehabbed, the Wizards kept him engaged. Sheppard brought him in on trade talks and free-agent discussions. He picked Wall’s brain on draft picks. “He has a hell of a grassroots network,” says Sheppard. With McLean, Wall studied pick-and-roll coverages. During games, Brooks employed Wall as an extra assistant coach. “He’s a savant,” says Brooks. “There were times he would say something to me and then, boom, what he said would happen right in front of us. He just knows the game.”

The basketball floor is familiar. Where Wall spends his downtime is not. His younger sister, Cierra, was the first in the family to graduate from college. Wall intends to be the second. He’s taking online courses at Kentucky, pursuing a degree in business management, fulfilling a promise he made to his mother to finish school. He’s in marketing and math classes this semester. He watches lectures twice a week, usually early in the morning. He studies three hours a day, completes projects, takes exams; Wizards vice-president of p.r. Scott Hall proctored one of them.

In January, Wall returned to Wizards practice. Clips of the workout quickly went viral. A step-back jump shot. A pull up three. A defense-splitting dunk. By March, Wall was going full bore. “He played out of his mind,” says McLean. “At first you’re just trying to get him back. Now you can see an All-Star—maybe better.”

***

In late November, Wall mingled at a charity event in Southeast Washington. His commitment to D.C. has been unwavering. He handed out 1,000 meals and 150 grocery cards over the Thanksgiving holiday. His foundation raised more than $500,000 for rent relief for coronavirus-impacted tenants in Washington’s poorer Ward 8. He donated 2,300 N95 masks to area hospitals in memory of his mother.

His commitment to the Wizards, it turned out, was shakier. Hours into free agency, reports surfaced that Wall wanted a trade. At the time, Wall offered a terse “no comment” when asked about the report; Sheppard said there were no plans to trade Wall—only to move him days later.

Don’t be fooled: The Rockets wanted off Westbrook as much as they wanted Wall. Wall is owed $132 million over the next three years, a contract thought to be untradeable—except when exchanged for an equally colossal albatross. At 30, Wall will begin this season shrouded in uncertainty, damaged goods until proved otherwise.

Wall vowed to SI that he will. “I averaged 20 [points] and nine [assists] on one leg,” he says. “What do you think I can do with two?” The Rockets are counting on it. Houston played at the third-fastest pace in the NBA last season, a Mike D’Antoni–led sprint offense that is expected to continue under Stephen Silas. James Harden, on his third backcourt partner in as many seasons, remains the Rockets’ engine, but Houston is loaded with shooters, including Ben McLemore, Danuel House and P.J. Tucker, each of whom hit 35% or better on threes last season. A player who can get them the ball is useful, and Wall, when healthy, is among the best at it. Before trading him, Sheppard gushed over how Wall would enhance the Wizards’ firepower. “I still think the league needs true point guards,” Sheppard said. “Point guards now are trying to score first. They can’t read defenses anymore. That’s why you see so many teams use zone defense or junk defenses. You don’t have guys who try to get you organized. John is a throwback to that. I don’t think he is ever going to look to score first. He knows how to run a team.”

Despite Wall’s frustration with the Wizards’ prioritizing of Beal, his teammate of eight seasons, the two remain close. “I wish him the best,” Wall said at his Houston press conference. “I told him, ‘Go keep doing what you’re doing. You’re that franchise guy. This is what the organization wanted.’ He’s earned that.” Of Harden, who has eyed a trade of his own, Wall expressed confidence that he wants to stay. “We’ve been on the same page since I’ve been traded,” Wall said, though, Harden’s absence from the first day of training camp suggests issues remain. The NBA has carried on without Wall. Stephen Curry and Damian Lillard battle for the label of top point guard. Kyrie Irving will return from injury this season and rejoin the fight. Young stars Luka Donˇci´c and Trae Young are not far behind. Among the elite, Wall is an afterthought. Asked about that perception, Wall chuckles. The NBA has seen him play with bad knees. It’s seen him play through a painful foot. It’s been years since it’s witnessed him with neither. “I’ve been through all types of things in my life, all kinds of obstacles,” says Wall. “God gives his toughest battles to his strongest people. Keep doubting me. I’m healthy. I’m back.”