College athletes are now allowed to profit off their name, image and likeness, and the landscape may be changed forever.

The Wharf isn’t an unassuming place.

This lavish open-air event space hugs the Miami River, boasts seven distinct bars, a half-dozen food trucks and a waterfront deck normally lined with small yachts. Green artificial grass weaves throughout the complex, ornate flowers drop from the ceiling and a string of lights zigzag overhead.

The Wharf throws some of the city’s most electric parties, frequently playing host to sports and musical celebrities who sip colorful drinks, sign autographs and pose for photos. The list includes soccer superstar David Beckham, actress Priyanka Chopra, singer-songwriter CeeLo Green and, in a more local sense, Miami Hurricanes quarterback D’Eriq King.

Because of NCAA rules prohibiting college athletes from earning compensation, King’s appearances at The Wharf are only for pleasure—not pay. If he signs a few autographs, he receives only a thank you. If he poses for photos, he gets a (cash-free) handshake. And if he orders a drink or meal, he foots the bill himself.

On Thursday, King is planning another trip to The Wharf.

This time, he’ll get paid.

“It’s long overdue,” King says. “I’m going to be one of the first people to make money from my name, image and likeness. We are going to show the country it’s here.”

In a transcendent day for American sports, thousands of college athletes across the nation are eligible to do something they never, legally, have before: profit from their own likeness through product endorsements, business ventures and public appearances.

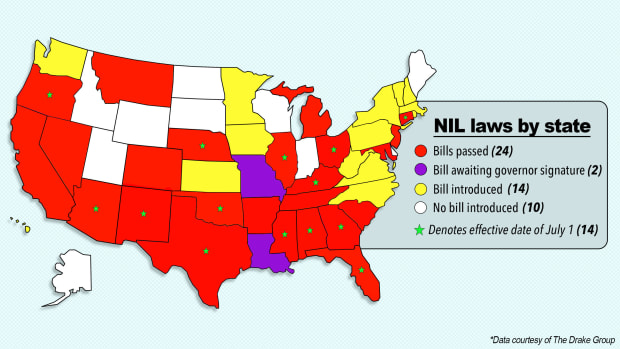

The NCAA’s long-standing constraints on athlete pay finally collapsed this year amid a sweeping political movement against the association’s archaic amateurism model. Two dozen states have passed laws governing compensation, as many as 14 of which take effect Thursday.

In response, the beleaguered governing body of college athletics took a wrecking ball to its already crumbling bedrock of antiquated rules, permitting all athletes to earn name, image and likeness (NIL) compensation in a seismic shift for a notoriously old-fashioned organization.

Previously barred from marketing themselves, athletes are expected to dive head first Thursday into an uncharted ocean, hoping to cash in on this billion-dollar industry. Businesses, big brands and even boosters, for so long directing money only to universities, have geared up to explore this untapped market.

In deals weeks and months in the making, high-profile college football and basketball players, and others with large social media followings, were poised to enter into contracts. There are grand announcements planned and live public events scheduled.

For instance, King, using the new digital marketplace Dreamfield, will secure an endorsement deal with The Wharf in an afternoon signing ceremony followed by a paid appearance at the club Thursday night.

Thousands of miles west of here, Fresno State women’s basketball twins Hanna and Haley Cavinder will sign one of the biggest deals yet, inking with Boost Mobile in an endorsement deal.

In Iowa, Hawkeyes guard Jordan Bohannon has a full day. He plans to begin selling his own designer apparel; he’ll enter into an entrepreneurial deal with VIDSIG, an app similar to Cameo where fans can book him for virtual chats; and he’ll finish with a paid appearance at a local business.

“It’s awesome. It’s a special moment in my life. Some athletes are going to be signing some pretty big deals with some national products,” says Bohannon, long an outspoken proponent of athletes’ rights even in the face of those critical of the new freedoms. “It’s good to see all these people pissed off about it happening. It makes me happy.”

While athletes cash in on long-awaited dough, chaos consumes this new space.

In an 11th-hour decision that divided many of its members, the NCAA passed a rule to permit individual schools—residing in states without a law—to create their own compensation rules. Others will follow their state statute.

The move will create precisely what the association worked for months to avoid—a patchwork of differing rules. Disparities will exist both between state laws and school policies, and among the state laws themselves.

Schools are scrambling to craft policies. Compliance staffs are bracing to be overwhelmed. And agents are offering six-figure advances to some NFL prospects, even if the legality of that is in question.

Most troubling of all, no one exactly knows who is supposed to enforce any of it—and how.

“This is the only play for the NCAA,” says Blake Lawrence, the CEO of Opendorse, one of the largest sports tech companies in the NIL space. “They need chaos. It’s the only way for them to get a federal bill faster.”

Sonny Vaccaro describes it as a mountain crumbling.

Several years ago, he swung one of the first pickaxes into the NCAA’s amateurism structure, a thrust that started the latest avalanche.

“The NCAA hung onto something that was totally illegal and immoral,” Vaccaro says.

The 81-year-old former shoe company executive was at least partially behind the Ed O’Bannon lawsuit against the NCAA, exposing one of the first cracks in the association’s model. Last week, the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Alston case—the NCAA lost, 9–0—further fractured the foundation.

History will view the two cases, both antitrust lawsuits, as small setbacks compared to the latest devastating blow from state lawmakers. Twenty-four states have passed NIL laws, the first in California in 2019 and the most significant in Florida, which set this 2021 timeline.

The state-by-state movement is a representation of the American public’s shift on the idea of amateurism, a striking difference to just seven years ago when Vaccaro and O’Bannon took criticism during the 2014 trial.

“That’s the thing that hurt, to watch Eddie be demeaned,” says Vaccaro, speaking from his California home earlier this week. “But, in the end, we did it. It’s monumental. It’s the best thing I’ve ever done in my life—and I signed Michael Jordan.”

If anyone predicted how this played out, it’s Tom McMillen, the former NBA player and U.S. Congressman from Maryland who is now the president of Lead1, which represents the athletic directors of the Football Bowl Subdivision.

In 1992, McMillen authored a book detailing the doom that may await college athletics in light of the rapid increase in coaching salaries—the driving motivation in the latest athletes’ rights movement.

“We had just passed the million dollar mark for a coach’s salary,” recalls McMillen. “My comment at the time was, if you don’t slow the arms race down, expect one on the student athletes’ side. That’s the story of the last 30 years.”

Ironically, the spark that lit college football’s big-money inferno came from the same high court that slammed the NCAA earlier this month. The 1984 Supreme Court case, NCAA v. Oklahoma Board of Regents, released television rights to conferences, resulting in the now multimillion dollar league TV contracts and escalating salaries. Fifty of the 130 FBS head coaches last year made at least $3 million, according to a USA Today database.

In a fit of irony, it was NCAA president Mark Emmert who, in a way, struck one of the first matches. As LSU’s chancellor in 2004, he made Nick Saban the highest paid coach in the country with a salary of $2.3 million.

Nearly two decades later, as head of the NCAA, Emmert faces the most significant crisis in his nearly 11-year presidency. His 18-month fight for Congress to pass a uniform bill to govern NIL by July 1 failed. The group of school presidents he oversees, the NCAA Division I Board of Directors, the true decision-makers within the association, has eschewed a more permanent NIL policy for a temporary, minimalist solution that charges the schools with creating their own rules.

In a way, the NCAA has washed its hands of one of the more significant issues to arrive at its doorstep, a move that further eviscerates its authority and has incensed its highest-ranking member schools. It comes a year after the association’s neutral approach to the COVID-19 pandemic led to a fractured membership.

The NCAA declined multiple requests from Sports Illustrated to interview Emmert.

“This really puts in question the value of the NCAA. Other than running championships, what’s their value?” says an industry source who wished to remain anonymous.

Castigated by U.S. senators, manipulated by state lawmakers and roundly loathed by the American public, the NCAA’s stability is at an all time precarious position. From within, even one of its most powerful executives has routinely landed blows to its broadside.

“I think we all expect more out of the national association than what we’ve seen of late,” SEC commissioner Greg Sankey told SI in an interview earlier this month. “We have a governance system that is not the most nimble. I’m sure that’s not breaking news.”

Vaccaro, a proverbial passerby witnessing the trainwreck, is awash with satisfaction. But the NCAA’s illegal model isn’t yet destroyed, he says. The fight isn’t over. State and Congressional lawmakers have the NCAA on the ropes.

“Knock them out!” barks Vaccaro.

“The mountain hasn’t crumbled yet, but it’s certainly a good place to be. That last kick, last pounding, that last stone … it’s coming.”

In 2014, in the midst of his junior season at Georgia, Todd Gurley was on a tear.

He had racked up more than 900 all-purpose yards, scored nine touchdowns and was dubbed a Heisman Trophy favorite.

Then, two days before his sixth game, Gurley was suspended amid an NCAA investigation that later uncovered he had earned at least $3,000 from selling signed memorabilia. He missed four games because he made money from his name, image and likeness.

Stories such as this one are plentiful. For instance, just six years ago while at LSU, running back Leonard Fournette says the NCAA forced his family to return thousands of dollars they earned from a product apparel line branded with his BUGA Nation mark.

“How much money would I have made from all of those No. 7 jerseys at LSU?” Fournette says. “I could have been straight (with cash) before I was straight.”

On Thursday, these actions, if reported properly to schools, will be legal. Athletes can earn money along a wide range of avenues: a public appearance endorsing a product at a local restaurant or an autograph session at a grocery; a live youth camp at a hometown park or private instructions in their backyard; their own clothing line or their own shoe brand.

Most athletes’ compensation will come through social media and be arranged via digital marketplaces, allowing them the ease to strike deals from their homes with a push of a button. A majority of college athletes—those without the star power to land powerful agencies and mega deals—have already created profiles on a wide range of these digital marketplaces. They match players with brands in the same way that a dating app pairs couples.

“We view NIL as not just a financial opportunity, but a balance shift of empowerment,” says Luis Pardillo, CEO and co-founder of Dreamfield, the Florida-based digital marketplace King plans to join. “This puts the power back in the hands of the athletes.”

King’s appearance on Thursday at The Wharf is not only one of the first such live NIL events from a college athlete—it’s also the completion of a journey for two Florida quarterbacks. King and Florida State’s McKenzie Milton will hold simultaneous NIL events Thursday in a plan orchestrated by Dreamfield. Financial details are not being disclosed.

That’s one of the great mysteries of NIL—exactly how much money is in it? No one really knows.

“Nobody has had access to these people—ever,” says Henry Hays, the founder of MatchPoint Connection, a Baton Rouge–based NIL marketplace. “I know one thing, we’re going to see some pictures of athletes at a 9-year-old’s birthday party because they are paid to be there. There’s a market for that in the south.”

Jim Cavale, CEO of INFLCR, another digitally based NIL company, believes some of the NCAA’s top stars and those with a large social media following—of which many women athletes have—can reach the six figures annually. The income for others may depend on how much work they put into their social media brand.

Each social media follower is worth about 80 cents in annual compensation, Cavale says, citing one advertising standard. But that number will fluctuate depending on an influencer’s actions.

Do they interact with followers? Do they post frequently enough? Do they have a defining characteristic or skill?

“Everybody is asking what’s going to happen on July 1,” says Cavale. “While there’s going to be stories of deals, it’s going to only be the beginning for athletes to start building a business. Businesses aren’t built overnight.”

Lawrence, the Opendorse CEO, says he expects hundreds of thousands of individual NIL ventures to be struck on Thursday and in the immediate days after. NIL reports will flood into school compliance offices, who, given the NCAA’s latest proposal, must create policy, enforce that policy and compliantly manage their athletes’ NIL activity.

“Aside from the top of the top, none of the schools are ready for it,” Lawrence says. “Everyone is underestimating how challenging this is going to be.”

You don’t know Kole Taylor, and you might not even recognize his name.

But in the college football hotspot of Baton Rouge, the LSU tight end is famous—at least his shoe is.

During a game between LSU and Florida last December, Taylor’s size 14 cleat was partially responsible for the Tigers’ upset win over the sixth-ranked Gators. In the final seconds, with LSU nursing a three-point lead and in control of the ball, UF defensive back Marco Wilson was flagged for a 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty for tossing Taylor’s shoe 20 yards down the field. It happened after LSU was stopped on third down. Instead of a punt, the Tigers were awarded a game-securing first down.

And thus, The Shoe Game was born.

“This year, if that happens, Kole would have three offers from shoe stores in Baton Rouge before the team plane lands back home,” says Hayes.

However, in some states, Taylor would be restricted from immediately entering into such contracts. In one of the most notable differences among state laws, some require athletes to have their ventures approved before they are executed. It could mean athletes missing out on income derived from viral marketing sensations like Taylor’s shoe.

While their foundations are similar, state NIL laws do differ slightly. Some even include provisions that may be more restrictive than the policies that schools in states without a law eventually create. For example, Mississippi’s state NIL law restricts recruits from entering into NIL deals. Florida’s statute requires NIL education. Texas prohibits athletes from striking deals with a long list of industries, including gambling, alcohol and drugs. Alabama’s law requires a days-ahead approval first from the school.

Long thought to have the advantage, could the schools in states with an NIL law now be behind the curve? It’s a difficult question to answer. It first depends on how athlete-friendly schools in states without laws make their rules and how quickly they can make them (some might not be ready by July 1). Schools have almost complete freedom, aside from NCAA-mandated prohibitions around pay-for-play or recruiting inducements.

Lawrence, who is frequently on calls with university administrators, says programs are split on how restrictive or permissive to make their rules.

In a restricted model, schools are at risk of being lambasted by the public and their own athletes and setting themselves up for a disadvantage against rival programs. In a permissive model, schools are in jeopardy of facing conflicts with their own sponsors or even violating licensing agreements.

“I’ll get off one call and they’re like, ‘How do we maximize this?’” Lawrence says. “Next call is, ‘How do we restrict this?’

“It’s wild.”

One of the most significant provisions schools are weighing involves licensing and trademarks. Should they grant permission for athletes to wear school logos in endorsement deals? At least one state law, Louisiana’s, specifically allows it if the school approves. But the South Carolina law prohibits the use of logos.

The South Carolina law does not take effect until next July, but at Clemson, athletic director Dan Radakovich is modeling his NIL rules off of the law.

Administrators who spoke to SI say they expect most schools’ NIL rules will mirror a combination of state laws.

For instance, Clemson will not allow athletes to use school marks in NIL ventures, as its state law reads, Radakovich says.

“Is that a big deal?” he asks. “We don’t know. Time will tell.”

Another pressing question: How much involvement can a school have in facilitating NIL deals? In the NCAA’s original legislation, programs were strictly prohibited from such, but the minimalist proposal passed Wednesday isn’t as clear. At least six state laws are silent on an institution’s involvement, presumably making such activity permissible.

One AD in a state without a state law told SI that his policy will be silent on institutional support, providing his program flexibility. He hopes his school doesn’t have to get involved in facilitating athlete deals. But will others?

“That’s my biggest thing,” he says. “As soon as we’re allowed to be involved, it’s a pay for play. People will be brokering and setting up deals.”

State laws still have their advantages, says Darren Heitner, a sports law professor at Florida who helped author that state’s statute. Schools in states without a law have a “very small runway” to create policy and educate athletes, while those with a state law have been gearing up for this for months.

In the last week, even before Thursday, five states saw bills or orders signed into law. State statutes provide schools a guiding set of principles and protection from potential legal issues.

“If the state law says X and the school is following X, someone may want to challenge the state law. That’s O.K., but it gives insulation to the school,” says Greg Clifton, a sports attorney based in Arizona and a former agent.

Also, state laws aren’t unchangeable. In fact, Corey Staniscia, a political aide who helped write Florida’s state bill, says he’s gathering information to potentially amend the Florida bill, if need be, as soon as this fall.

In the end, states might have to change, says Hayes. He believes that most school policies, at least in the Power 5, will afford athletes a mostly unrestricted market. Why?

“They’re in a perpetual state of recruiting. What, are they going to say, ‘no’ to these athletes? That gets out,” he says.

In the meantime, coaches are searching for ways to gain an edge in recruiting. Agents have advised their coaching clients to facilitate contracts for athletes and recruits with local businesses, an industry source tells SI.

“If you’re not having those conversations and lining up deals with your guys, you’re behind,” the person says.

Many inside the industry expect an excessive number of NIL deals, at least for the first two to three years. Booster-owned businesses and big-name brands, they say, will support the team by funneling donations to players in the form of endorsement and appearance arrangements that are, in many ways, now legal.

And if it is not legal, who enforces these state laws or school policies? Can schools, with overwhelmed and understaffed compliance departments, be trusted to report or even uncover violations? Some state statutes don’t even designate an enforcement entity.

It’s a free-for-all.

“Who gets in trouble?” Lawrence asks. “Is the kid arrested? Does the booster get fined?”

Emi Guerra started his career as a college kid at FIU who threw good parties.

Years later, he’s one of South Florida’s most influential hospitality marketers. His crown jewel is The Wharf, where on Thursday a local sports celebrity will make history. King, the Miami quarterback, is scheduled to sign his deal at 4 p.m. from the venue’s deck seating on the bank of the Miami River.

For now, this is a single booking public appearance. But the future might hold more transactions between King and one of his favorite local spots.

“You’re in uncharted territory, but sometimes you’re able to do unique stuff in uncharted territory,” says Guerra. “Being one of the first is unique. Being the first is cool.”

Meanwhile, on the banks of another river, NCAA headquarters braces for a movement that its staff and members have fought against for so long. A new era of college sports has arrived. And for the Indianapolis-based association, the unequal laws and policies across the country are “a disaster scenario” that can be solved only by a federal NIL bill from Congress, says Ekow Yankah, a law professor at the New York–based Yeshiva University. While lawmakers support passing uniform legislation on Capitol Hill, Republicans and Democrats cannot agree on the scope of a bill. Though talks are expected to reignite soon, some wonder if legislation will get passed by the calendar year.

If Congress does adopt a federal bill, more questions then loom. What happens to agreements between athletes and brands made under state law and school policy?

“Once you let toothpaste out of the tube, you can’t put it back in,” says Bryce Choate, a former Oral Roberts track and field athlete and the student representative on the NCAA D-I Council.

McMillen, the former Congressman, believes college sports needs a new national model of operation. But, he says, “I don’t know how you get there.”

Dan Gale, president of the college athletics consulting firm Leona Marketing Group, compares NIL to a hurricane. It will roar ashore, cause devastation within college athletics and then see the industry rebuild.

“The impact is going to be weird, bad and ugly, because it's dirty,” he says “In three years, we’ll be fine. It will be different, but it will be fine.”

The hurricane is on the doorstep of college sports, its outerbands lashing the coast before a full landfall in the coming days.

“It’s going to be a clusterf---,” says one college athletics source. “Buckle up.”

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories

More NIL Coverage:

• Q&A: Prominent Attorney on NCAA's SCOTUS Shutout, NIL

• The Supreme Court Sends a Message to the NCAA

• The Hidden Industry of Name, Image and Likeness