The Socratic hooper and MVP is searching for the Sun’s first WNBA title.

In the first quarter of a mid-August game against the Lynx, Jonquel Jones caught the ball at the crest of the three-point arc and saw a defense arrayed against her. She’d earned the attention. Jones, a 27-year-old Bahamian with bungee-cable limbs and a full-faced smile, spent the regular season as the best player on the WNBA’s best team, averaging 19 points, 11 rebounds and nearly three assists for the 26–6 Sun. She has a guard’s jump shot and sense of the floor’s geometry (a 57.1 effective field goal percentage), a center’s leverage and reach (two and a half combined blocks and steals nightly) and a coach’s understanding of which of these attributes the game requires at a given moment. Even having missed a half-dozen games to play for the Bosnian national team in June’s EuroBasket tournament, she has distinguished herself by traditional and advanced metrics alike, leading the league in double doubles and player efficiency rating. The MVP vote was almost unanimous. “Of course, ten thousand percent,” said DeWanna Bonner, the Sun’s second-leading scorer and twice a champion with the Mercury, when asked during the regular season whether Jones was in line for the award. “There’s no questions asked.”

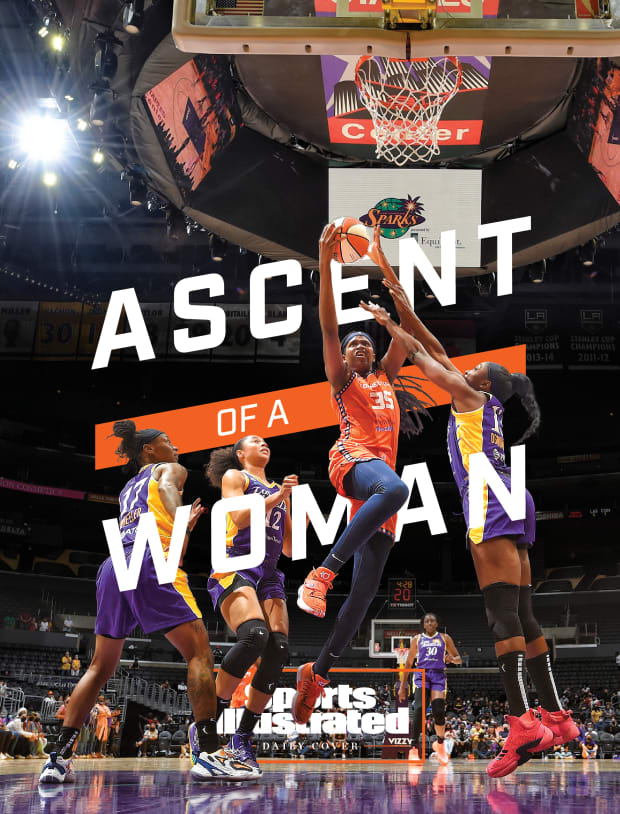

Juan Ocampo/NBAE/Getty Images

So Minnesota’s Damiris Dantas stepped into Jones’s space to guard against the three (alongside everything else, Jones hits triples at a 36% clip) while Sylvia Fowles, four times the league’s Defensive Player of the Year, lay in wait. Undaunted, Jones dropped into a crouching dribble, shouldered Dantas backward and spun toward the middle of the floor to drive at Fowles. As Fowles jumped to contest, Jones performed a half-pirouette midair and flicked a backhanded layup just over top of Fowles’s distinguished fingertips. The bucket dropped, and the official tacked on a foul. While Jones bellowed and pumped her fist, Brendan Glasheen, the Sun’s play-by-play commentator, searched for a verb for whatever she had just done. He settled on “finagled.”

Five years into her pro career, the 6' 6" Jones belongs to that category of cross-positional preternaturals presently running the W, fitting comfortably into the ranks of Candace Parker, A’ja Wilson, Breanna Stewart and Nneka Ogwumike. On her best nights, she is the most audacious of the bunch. Jones seems at times less like a single versatile player than like a handful of wholly discrete athletes—stretching to full length to wall off the opponent’s rim or hoover up a rebound one moment, feathering a fadeaway off the glass the next. “When she gets in that zone—the confidence to shoot a three, to dribble 94 feet and make plays, to Euro-step to the rim—there’s such a joy,” says her coach, Curt Miller.

Witnessing that joy, the unfamiliar viewer might assume she’s taken the prodigy’s path common to the Stewies and A’jas of the world—expansive talent sharpened quickly into expertise. (Wilson stepped into the league and averaged 20 points a game as a rookie; Stewart, 18.) Instead, Jones has made a rare and grueling ascent, a station-by-station trudge to her sport’s highest echelon. Jones is the kind of gumption parable invoked at basketball camps around the world: a onetime high school varsity cut, the first player in WNBA history to be named its Most Improved and then its Most Valuable. But as the Sun begin their push for the franchise’s first title—they open their semifinal series against the Sky on Tuesday night—Jones insists that a retroactive reading misses the point. It’s not that she’s so much better today than she was a year, or five, ago; it’s that she’ll be better still tomorrow. “The moment I feel like I’m settling is the moment I should be talking about retiring,” Jones said in August, sweating through the sorbet orange of her practice uniform. Her career sits atop a thesis: A built game is better than a born one.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

When a 14-year-old Jones disembarked at the Baltimore/Washington International Airport, she might reasonably have expected a hug and a few welcoming words. Instead, Diane Richardson—her new coach and ambassador into the world of high-level prep basketball—smiled and dropped a shoulder into Jones’s, testing her balance atop bony legs. She issued a challenge: “Can you bump in the post?”

Jones came to the United States in 2008 from Freeport, Bahamas, a storm-battered city where a hurricane once ripped the roof from her family’s home. She passed her preteen years largely on the few basketball courts available to her, settling into a rangy, adolescently awkward style that nevertheless distinguished her in her neighborhood’s contests—in which she was often the initiator, almost always the only girl and invariably the best player. (After sundown, she’d launch a glow-in-the-dark ball, a Christmas gift, at a milk crate affixed to a light pole on her street.) Watching their daughter drub the local competition, Jones’s parents reached out to Richardson, the coach at Riverdale Baptist High School’s esteemed program in Upper Marlboro, Md., whose alums populated Division I rosters across the country. They asked whether Richardson would help facilitate Jones’s move to the U.S.; Richardson agreed, and stepped into the role of Jones’s legal guardian. “There will always be a place for you,” Jones’s father, Preston, told her before she left, “but what you want to accomplish, what you want to achieve—don’t come back here, because it’s not possible.”

From the airport, Richardson drove Jonquel straight to a Riverdale practice, where the newcomer balked at both her own off-the-plane look (“I didn’t put on any lotion that morning. I was super ashy!”) and the crispness of play. “Honestly and truly, she could have sent me back to the Bahamas,” Jones says, “because I wasn’t on the level of the U.S. players.” She scuffled through that first session, fumbling passes and rushing shots she’d made comfortably in the slower-paced games back home. Soon thereafter, Richardson placed her on the junior varsity squad, deeming it better for her development than daily dust-eating sessions at the hands of the top team. “We were nationally ranked, and, skill-wise, she wasn’t there,” Richardson says. “She was a skinny kid; she’d get a rebound and somebody would just take it from her. She was fast, but her legs were a little bit long. Her dribble was way too high.”

Any teenager might chafe at a demotion; Jones thought of her father’s warning and despaired. “I don’t want to go home as a failure,” she told her coach. Riding in Richardson’s car one night, Jones broke down in tears. “You’ve got to put some more time in,” Richardson told her. “Just because you’re my kid doesn’t mean you just play.”

The practice floor became both solace and solution. “I don’t know if she was trying to prove me wrong or what,” Richardson says, “but she worked.” Jones’s lack of polish, a hindrance to her standing in the Riverdale program, held a hidden benefit. She had no established tentpole to her approach, no facet that she tended at the expense of well-roundedness. In some ways her prep school dedication held to the montage-ish patterns common to future pros; Jones rose at the obligatory 5 a.m., hoisted the thousand jumpers on the driveway hoop before breakfast, logged marathon six-hour sessions in the school gym, etc. But guided by Richardson—who had played point guard at Frostburg State in the ’70s, and who would make sure any protégé of hers could dribble and pass—the sessions involved as much exploration as repetition. Certain drills were designed to commit post moves to muscle memory; others sent Jones scurrying from sideline to sideline, collecting intentionally errant passes and firing jumpers as fluidly as possible. One was nearly a metaphor, conceived to show her the breadth of what she could do with her lengthening body. (She entered high school 5' 8" and left it 6' 1".) Jones would perform an elaborate choreography of dribble maneuvers among arrayed cones, dash to the rim and, the instant before leaping for a layup, swoop an arm downward and snatch the last one from the ground—traversing the span from floor to backboard in a split second.

“We wanted her always in motion,” Richardson says. “Always on her toes.”

Jones progressed to varsity full-time her junior year, her second in the States, and during her senior season averaged team highs in points and rebounds, leading Riverdale to a 39–2 record. She soared up the national recruiting rankings, from off the board to top-20 status. Her languid, long-armed jump shot and thickening catalog of countermoves earned her comparisons to Kevin Durant, another dimensionally improbable player who had called the D.C. metro area home, and Jones embraced the comparison without idolatry. “The first time I watched him,” she says, “I thought, ‘He really looks like me.’ ”

G Fiume/Getty Images

In 2012, Jones enrolled at Clemson, but she lasted just a semester there, having become sufficiently attached to her new home to feel homesick leaving it. In January, she transferred to George Washington in D.C., where Richardson had landed as an assistant. The NCAA’s transfer regulations kept Jones from competition for a year, but her practice habits made her a scout-team adept. During gameplan installations, she assumed the role of the opposing team’s best player, whether a shot-hunting two-guard or low-post brute. Jones embraced the chance to contribute, but there were ancillary benefits. Studying film on opponents, she’d pilfer moves; a shoulder-fake she learned for the sake of the impression would stick. The coaching staff took on the role of clip curators, cutting footage of Elena Delle Donne’s pivot work—the Mystics star’s pregame shooting routine eventually became Jones’s own—and Dirk Nowitzki’s splay-legged bankers. “I always get focused on one thing,” Jones says, recounting her year-by-year motivations: making varsity, getting college offers, building out a pro-ready game. “When I realized the WNBA was an option, I needed to figure out how I could fit at the next level.”

When she regained her eligibility, Jones put what she’d learned to use. She averaged more than 15 points and 10 rebounds in each of her three seasons at George Washington, winning the Atlantic 10 Player and Defensive Player of the Year awards her junior year, and only a shoulder injury that robbed her of 10 games kept her from repeating in both categories following her statistically superior senior campaign. Jonathan Tsipis, then GW’s coach, recalls the team’s trip to Freeport in 2014 for an early-season tournament that doubled as a homecoming. After North Carolina State made a second-half run to cut into GW’s lead, Jones called for the ball on the block, determined not to let a full-circle moment slip. She pivoted hard over her right shoulder and stemmed the tide with a jumper like a final project: “A Dirk fadeaway,” Tsipis crows, “with a little bit of Hakeem [Olajuwon] to it.”

The Sparks selected Jones sixth in the 2016 draft; when Connecticut swung a deal for her shortly thereafter, Miller says, the team saw her as a gamble. She could rebound, but it remained to be seen whether her studied scoring game would hold up. Worst case, the Sun got a contributor; best case, they had their own prototype to run out opposite the likes of Stewart. Miller was drawn to the rarity of Jones’s skill set—“the potential of the offensive versatility, her touch for her size on the perimeter.” More alluring even than that, though, was a player whose tape showed month-to-month overhauls that would take most athletes years to pull off. Jones was a Socratic hooper; she’d learned how to learn.

M. Anthony Nesmith/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Made up of just 12 teams of 12 players, the WNBA has perhaps the most densely concentrated talent pool in major professional sports. So if stretches like the five-game stint the Sun faced in August—two against Fowles and the Lynx; one against the Aces, powered by Wilson and 6' 8" Aussie maelstrom Liz Cambage; two more against Ogwumike’s Sparks—are not exactly rare, they are highly instructive, especially in sorting out the pecking order of the league’s superstar class.

Against her nearest peers and fiercest rivals, Jones shone. She was omnipresent in the two games against the Lynx: 37 points, 20 rebounds, six assists, three steals. In a rock fight against Vegas, she fortified the back line of the Sun’s defense, helping hold Wilson to four points on a career-worst 1-of-15 shooting. Across the pair against the Sparks, Jones put up 36 more points and pulled down 18 more boards. Connecticut won all five games, four of them by double digits, building out the middle portion of a 14-game winning streak, the longest by any team this season. “[Jonquel] plays the elite position in the world,” Miller told me afterward, ticking off the roster of frontcourt savants she’d just bettered. “It’s where the superstars of our league play; it’s the deepest and most talented position in professional women’s basketball. And she is at the top.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Jones’s pro career has carried on the pattern of deficiency-as-prompt; the way an X-ray of a healed bone shows a hardened line of calcification at the site of the break, her strengths point to the locations of onetime weaknesses. As a rookie averaging just seven points off the bench, Jones got “beat up,” Miller says, so she spent her first offseason packing on muscle. During her offensive breakout—an All-Star sophomore season and Sixth Woman of the Year–winning third season—her defense lagged behind; in 2019, she led the league in blocks while leading the Sun to the Finals. Over WNBA offseasons, Jones moonlights for UMMC Ekaterinburg, a Russian powerhouse with the talent-acquisition strategies of the Avengers, chasing Stewart around screens and standing up to the battering-ram backdowns of Brittney Griner. (Giving up her spot on the Bahamas’s national team and signing on with Bosnia, one of a number of countries that fast-track citizenship for world-class athletes, allowed her access to the European league.) And when the classical center Brionna Jones slotted into the starting lineup in place of the injured Alyssa Thomas this season, Jonquel moved closer to the perimeter. She’s nearly doubled her career assist average.

The year’s primary project, though, has centered on aggression. A versatile approach can easily become a reactive one; the Sun’s coaches have called on Jones to develop a superstar’s healthy ego and statistical gluttony. (“How many rebounds do I have?” Jones asks Awvee Storey, the Sun’s player development coach, during games. His answer: “Not enough.”) “Woo!”—Jones’s preferred syllable—now serves as the soundtrack to Connecticut practice sessions. It is a cross-category call to action: a plea for the ball, a signal for a teammate to cut, a boast over a behind-the-back pass slipped through for an easy scrimmage bucket. Jones hasn’t watched film of her lone Finals appearance in 2019, in which she averaged 19 and 11 but fell to Delle Donne and the Mystics—“It still hurts really bad,” she says. But its lesson, about the every-play approach required to win a championship, has stuck: “My mentality is different.”

In one of the Sun’s final regular-season games, before their two-round playoff bye, Jones worked over the Liberty: 18 points, 13 rebounds, four assists, a series of post pivots pulled straight from Richardson’s driveway. At one point she executed a baseline fade—quiet line of body, soft arc of ball—that might once have seemed an homage and that is now all her own. The evening had the mood of a tuneup, as if she were testing her various components in preparation for the playoff gantlet to come, and in the hours afterward Jones made a customary call to Richardson: half maternal check-in, half advice on working through double teams. “She stuck it out with me and told me all the things that I needed to be successful, and I did it, and look at me now,” Jones says. “I’ll never not listen to her and take her words to heart.”

The next month has the outline of a culmination, for Jones and the Sun. “She’s the ultimate chess piece; every game there’s a different advantage,” Miller says. “The next step is for her to take us to the mountaintop.” But to those who have followed it longest, Jones’s story resists endpoints, even those as tidy as a championship. Asked whether her most accomplished student could still improve, Richardson let slip a parental chuckle, as if the image in mind were still of the knob-kneed kid at the airport. “She could get a little bit stronger.”

More SI Daily Covers: