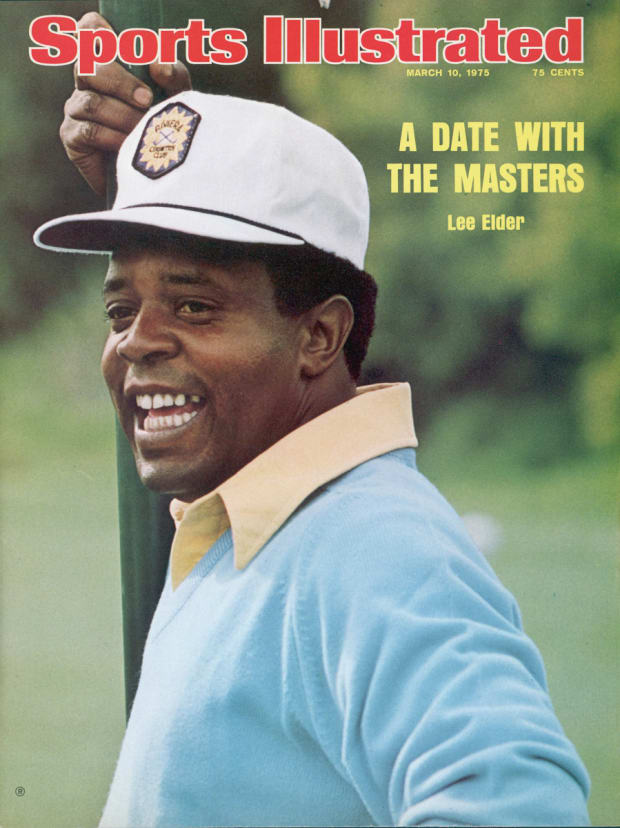

In 1975, Lee Elder became the first Black golfer to play at the Masters. This year, he returns to Augusta National for yet another historic moment.

Two phone calls, 46 years apart. Both from the chairman of Augusta National Golf Club, both to the same man.

The first call came in April 1974. U.S. golf had an abhorrent racial history, littered with outright segregation and de facto segregation, with ever-changing qualification rules to keep the sport as white as it could be. No Black man had ever played the Masters before. But Lee Elder had just won the PGA Tour event in Pensacola, Fla., earning automatic qualification for the Masters.

Augusta National’s Clifford Roberts, the man who built the Masters into an institution, called Elder. Roberts was either a virulent racist or a man of his time, depending on the telling, but he was also extremely media-savvy, and he knew that the club needed to at least look like it was embracing Elder. He officially invited Elder to the Masters and expressed his personal satisfaction at Elder’s earning an invitation.

“I think he wanted me to say ‘yes’ right then and there,” Elder told Sports Illustrated last week. “I said, ‘Well, I'll have to think about it, Mr. Roberts. I'll let you know.’ ”

Elder was wary—not just of how white America would treat a Black golfer at the Masters, but of being used. Earlier, when a group of politicians had pushed to get him a special Masters invitation, he resisted. He wanted to earn it. Now he had. But he still made Roberts wait for an answer. Elder wanted to talk to confidants before accepting, but also: He had waited long enough. He wanted Roberts to wait. He finally said yes and broke the Masters’ color barrier the next year.

The second phone call came last fall.

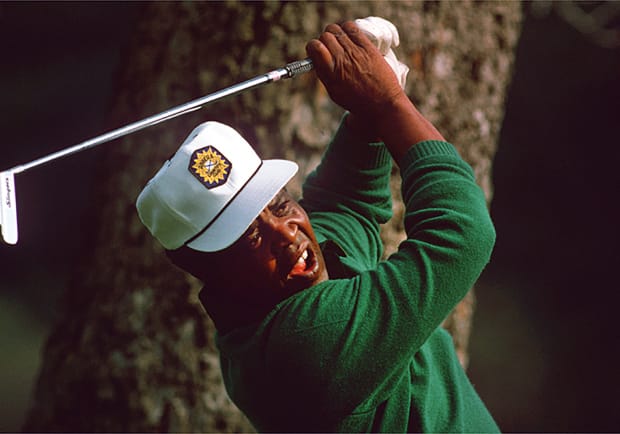

In his Southern California home, Lee Elder keeps a copy of SI with Lee Elder on the cover. The magazine is not just a keepsake for him, because his professional life was not just a golf career. He does not own a Claret Jug or Wanamaker Trophy or a spot in the World Golf Hall of Fame, but what he accomplished was probably harder.

“It cannot be captured with a trophy,” he says. “It is captured, I feel, within the person himself and what he thinks about what happened.”

Elder’s story is about being first, but also about being too late. It is about what he achieved, but also what he could have achieved if the U.S. did not burden him. Elder’s story is an important story for anybody who loves golf, but the rest of us cannot pick up the story like a ball on the green, remove all the dirt and place it back where it was. It is not our place to do that.

This is Elder’s story to tell, however he chooses to tell it.

Elder turns 87 this summer, but his memory remains sharp. He can tell you where he was staying—“the Albert Pick, which is straight down (Interstate) 40”—during the 1968 Greater Greensboro Open, the week that Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis. He remembers the unrest in the country, and he remembers Greater Greensboro being delayed and finishing Monday. He remembers going to Memphis himself the next year for the old Danny Thomas Memphis Classic—“It was named the Memphis Open at that time, and it became the Danny Thomas after that,” he says, correctly. He was leading the tournament Saturday when he hit what seemed like a great tee shot. He couldn’t find his ball.

“Middle of the fairway, left-center, and it was near a road and a fence,” Elder says. “And finally we found out that a guy jumped the fence, picked up the ball and took off with it. Nobody in the gallery said anything. … They picked the ball up and threw it out in the road when I was leading the golf tournament.”

He finished second that week, and he says that was a pretty good showing, what with the death threats and all.

Elder can tell you who should have played in the Masters before him. He remembers fellow Black golfer Pete Brown’s winning the Waco Turner Open in 1964, and fellow Black golfer Charlie Sifford’s winning the 1967 Greater Hartford Open and 1969 Los Angeles Open, and says that both should have received Masters invites both years but never did. A half-century later, the only fact in this paragraph that Elder did not accurately recite from memory was the year of Brown’s win. He was off by one year.

He remembers being in Pensacola in 1974 and having to beat more than the field.

“They had threatened me,” he says of some locals. “If I won the tournament, I’d never leave there.”

It was an extraordinary upset that he ever arrived there. Elder’s father was killed in Germany in World War II. Then his mother died. He was an orphan at 11. He played his first full round of golf when he was 16. He decided he wanted to be a golfer, but a Black golfer then was always a Black golfer, never just a golfer. In 1960, Elder met Ted Rhodes, who had worked with Sifford and had seen the atmospheric pressure get to other Black golfers.

“He did not want that to happen to me,” Elder says. “So he decided that he would travel with me, he was pretty much taking me under his wing. And we traveled the globe, driving pretty much most of the time.”

Rhodes gave Elder a lot of advice—some to apply on the course, some to apply off and this, to apply everywhere: “The one thing that I can always remember Teddy saying: ‘You know, it's so hard to get out of a situation. It's so easy to forget it.’ ” In other words: Don’t dwell on whatever is going wrong. Double bogey? Forget it. Missed cut? Forget it. Racial slur from a stranger calling your hotel room? Forget it.

No athlete should ever have to face bigotry, of course, but it is especially hard for a golfer to overcome. Virtually every tournament is a road game, and most are on private, exclusive property. Golf is also a game of nerves. There is no conventional rhythm, no chance to run up and down the floor or rely on athleticism for a few minutes. Except for occasional events, there are also no teammates to bail you out.

Simply because of his skin color, Elder was a perpetual outsider in the ultimate insider sport. That 1975 SI cover story detailed some of the slights and challenges:

Recently one of the tour's stars asked Elder to help a large Southern university recruit its first black golfer. Afterward Elder said angrily, “Here’s a guy who speaks two words to me all year and all at once my being black comes in handy. Stuff like that happens all the time.”

Elder won four PGA Tour events. He would win eight on the Senior Tour (now called the Champions Tour). The difference can be explained by his putting, which got better, or the fact that he picked up the game later than most of his peers, delaying his PGA Tour prime. But there is also the simple fact that he hit the PGA Tour in the ’60s and the Senior Tour in the ’80s, and it was easier to be a Black golfer in the ’80s.

“That was one of the reasons,” Elder says. “It had gotten a lot quieter.”

The turbulent U.S. summer of 2020 gave a lot of people time to think, including Augusta National’s Fred Ridley.

“The chairman called me himself, about 10 o’clock in the morning,” Elder says. “He said, ‘I want to know if you have time, and we can talk about something.’ ”

Elder had a pretty good sense of why Ridley was calling. Elder’s friend, three-time Masters champion Gary Player, had publicly pleaded for Augusta National to make Elder an honorary starter, alongside Player and Jack Nicklaus, to acknowledge his place in the club’s history. Player grew up white in South Africa, acutely aware of his privilege long before people said things like that. Player was not just nice to Elder; he pulled him close. When Player asked Elder to join him for the South African PGA event, Elder went because he trusted Player’s heart: “I knew that it was going to help and not harm anything.” Today, Player refers to Elder as “my brother.”

Elder had many years to think about his career, of the threats he received and discomfort he was made to feel, and this is how he chooses to tell his story now:

“There was really no mean person that I came in contact with my whole career on the tour. Because right away, I went out with the attitude that I'm going to make friends, and hopefully that they would want to make friends.”

And: “I wouldn't say the country did not welcome me, because I feel that the things that I have achieved, like on the United States Ryder Cup team, I tell you: That was one of the greatest experiences that I’ve ever had.”

And: “I have never, never had a bad moment of time at Augusta National. Even my first year, when I went down in 1975, [with] all of the threats and all the things that had been sent my way, I still felt comfortable when I went through those gates at Augusta National, because I knew that I was going to be well-protected.”

He thought about it, Mr. Roberts. He thought about it for a long time. And when Fred Ridley called, Lee Elder did not need to think about it anymore.

“I said, ‘Mr. Chairman, I have time for you anytime, sir.’ ”

Elder will be on the first tee Thursday.