The games are back, but a certain special element of sportsmanship will not return, for safety's sake. This is a remembrance to the 'Put 'er there'—to the soul shake, the hand slap, the high five (and low) five...

An opening sentence is a handshake, to paraphrase the novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, and it’s true that a good one draws you in, delivers you into capable hands and introduces you to a subject of interest—in this case, George (Shotgun) Shuba, for whom a handshake was an opening sentence.

In seven seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers, during the High Renaissance of major league baseball, Shuba played in three World Series, including in 1955, when Brooklyn won its only world championship, after which he married, went to work for the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and set about raising three children in his native Youngstown, Ohio. For the rest of the century, in two Maytag boxes in the basement, Shuba stashed every bit of his baseball memorabilia, with a single exception: a reminder of a minor league game in Jersey City on a cool spring Thursday when he was 21.

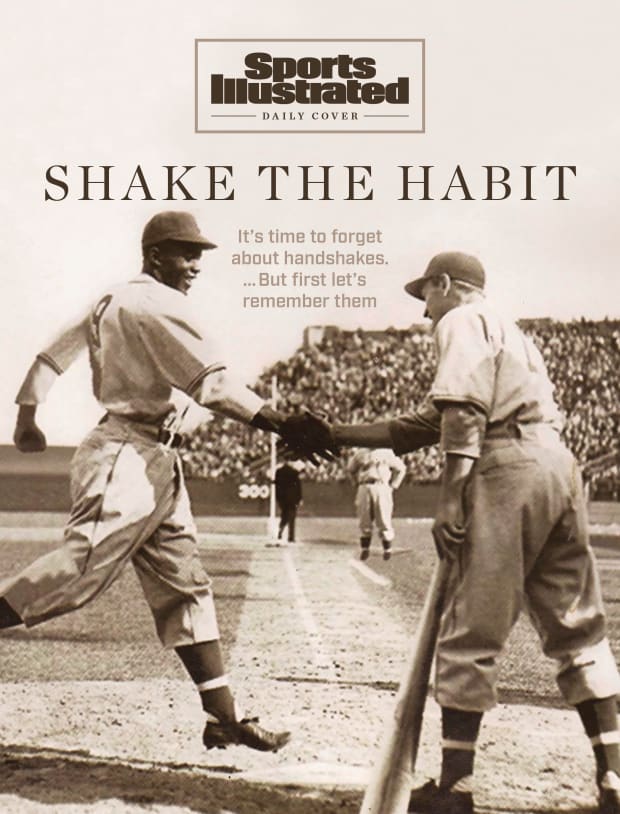

In the third inning of that game on April 18, 1946, a rookie debuting for the International League’s Montreal Royals hit a three-run homer over the left field fence off Little Giants lefthander Warren Sandel. The two men on base ran straight to the dugout after scoring, but the on-deck hitter—George Shuba—raced to home plate to greet his teammate. Before Jackie Robinson could step on the dish, Shuba was already shaking his hand. In a photograph of that moment, Robinson’s smile and feet suggest he is levitating, held up by Shuba’s right hand, though the reverse would also turn out to be true.

This was the first recorded instance of a black player and a white player shaking hands on a modern professional baseball field, and that photo hung above George Shuba’s recliner in Youngstown for half a century, the opening sentence to the rest of his life.

That picture started conversations. As a boy, Mike Shuba didn’t recognize his own father in the figure of the young ballplayer, nor did he know the world-historical figure of Robinson. But when Mike came home from school as a six-year-old, fresh from a kindergarten conflict, his father pointed to the picture above the recliner and said: “You look up at that photo. I want you to remember what that photo represents. You treat all people equal.”

“Dad didn’t ask to be the next batter up,” Mike says. “Nobody knew Jackie would hit a home run. But as Dad always said: ‘If you’re put on the spot, do the right thing and everything will work out fine.’ ”

George Shuba died in 2014. Mike is 58 now, and he still lives in Youngstown, where he holed up during the pandemic, washing his hands and social distancing like the rest of us. “Are we ever going to get back to handshakes?” he asked on a recent afternoon. “I don’t know.”

***

America’s top pandemic doctor would like to wave goodbye to the handshake. “I don’t think we should ever shake hands ever again,” Anthony Fauci said in April, because abandoning the ancient practice would not only curb the spread of the coronavirus, but it would dramatically decrease flu cases in America. “Just forget about shaking hands,” Fauci said. “We don’t need to shake hands, we’ve got to break that custom.”

But can we? In sports, the handshake has long held us in its grip. Perhaps too long, like those overeager greeters who pump your hand as if trying to draw water from a well. There are pregame handshake lines in soccer and at the net in tennis—a sport that begins with a handshake grip. Postgame, there are handshake lines in softball. And hockey players remove their gloves on two occasions: to punch out opponents and later (in the playoffs) to shake those opponents’ hands.

Like the hand itself—a clenched fist or an open palm—the handshake has its own duality. The handshake stands for integrity. “My handshake is my bond,” Reds manager Sparky Anderson once said. “I don’t need a contract.” This is called a handshake deal. But the handshake also stands for corruption. When boosters in the 1980s handed Kentucky basketball players money concealed in a palm, the result was known as a “hundred-dollar handshake,” though inflation has surely since robbed that phrase of its alliteration.

Paper money has become, in this pandemic, every bit as unsanitary and endangered as the handshake, which was never hygienic in the first place. A fan once approached the writer James Joyce and asked, “May I kiss the hand that wrote Ulysses?”

“No,” Joyce replied. “It did lots of other things, too.”

Likewise, when Jorge Posada was the Yankees’ catcher, he would urinate on his own hands in the spring to toughen them up for the long season ahead. “You don’t want to shake my hand in spring training before a game,” he said then, echoing the actor Paul Newman, who was once approached by a fan in the men’s room at Sardi’s while standing at a urinal, midstream, and thought: Do I wash before shaking his hand?

But a handshake is perhaps the least unsanitary thing that happens between players on a football field or a hockey rink or a basketball court, and it has more often born goodwill than illness.

More than any other segment of American life, sports have helped the handshake evolve over the decades, crawling out of the primordial ooze and walking upright as a soul shake, hand slap, high five, low five, forearm bash, fist bump, pound, bro hug and myriad other forms of “dap,” a word that emerged among Black American troops in Vietnam (possibly as a shortened form of “dapper,” or as an acronym for “dignity and pride”). And a good handshake remains a stylish accessory. If there was a patient zero for dap, a carrier who transferred it like a happy contagion to the world at large, it might be the former Oakland A’s pitcher Vida Blue, who gave President Richard Nixon what was then known as a soul shake when the Athletics visited the White House in August 1971. “That’s how we do it,” Blue told the world’s stiffest man, who eight months earlier had endured another awkward handshake with a spaced-out Elvis Presley.

Former Marquette basketball coach Al McGuire called these increasingly elaborate greetings “Knights of Columbus handshakes,” as if they were the secret greetings of a fraternal order, a signifier of solidarity—which they often are.

Paul Molitor, for one, developed a secret handshake with his Brewers teammate Rob Deer, and he credited it in part for his 39-game hitting streak in 1987. At the beginning of that run, during a game in Chicago, the two hitters failed to shake hands, and Molitor started the outing 0-for-4. But they shook before his fifth at bat, Molitor got a hit, and off he was! (This can work in reverse, too. Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg shook hands with heavyweight champion Joe Louis in New York in 1939, and immediately he went into a slump.)

Before 1970, baseball players were inclined to shake hands the old-fashioned way, like an insurance salesman sealing a deal. “I’m glad I don’t play anymore,” Hall of Fame Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto said after his playing days ended and he became a broadcaster in the Bronx. “I could never learn all those handshakes.”

***

The handshake has always been problematic in that way, but it has also been potentially dangerous. The animist chief Baoura of Niger—who died in 1994 at the age of 126—was said to possess a Handshake of Death, a lethal grip. The same could be said of former Yankees outfielder Hensley (Bam Bam) Meulens, who was once administered a grip test at the team’s spring training facility. Meulens squeezed the grip meter, which measures isometric hand strength, and broke it.

A powerful handshake has long been a sign of robust health and honesty, or so most of those aforementioned insurance salesmen would have you believe. Former heavyweight boxing champion George Foreman, his hands battered from years of battering others, today dreads shaking hands because men have always wanted to impress him with their vice grips. “To make matters worse,” he told Esquire after retiring, “now women are coming up with that firm shake.” But it was ever so. Gussie (Gorgeous) Moran, the postwar American tennis star, had a handshake that one writer said “would make Jack Dempsey holler Uncle!”

Some of these walnut-crushing handshakes, as they’re commonly described, indeed have malign intent. Playing off his reputation for pitching doctored balls, Gaylord Perry would coat his hand in Vaseline on the day before a start and shake hands with opposing hitters near the batting cage. Perry was getting into their heads, lubricated by petroleum jelly.

Few men, though, have done more reputational damage to the handshake than Soren Sorenson Adams, patriarch of the S.S. Adams novelty company, whose line of spring snakes, dribble glasses and coiled plastic turds—while impressive—could never hold a trick candle to his greatest invention: the joy buzzer, a small spring that administers a shocking sensation to the unsuspecting handshaker.

The joy buzzer hit the market in 1928, at a time when the handshakingest man in the world may well have been Art Fletcher. As the Yankees’ third base coach from 1927 to ’45—when Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio combined for 1,053 home runs—Fletcher shook more hands than most presidents. Which is saying something, as President Teddy Roosevelt shook 7,987 hands over three and a half hours on New Year’s Day of 1905.

After Ruth died in 1948, DiMaggio recalled the time, two years into his Yankees career, that he met the Bambino in New York’s clubhouse and first had physical contact with the legend. DiMaggio, the most debonair man in baseball, said of Ruth: “I felt just like a rube when he shook my hand.”

There is something about manual contact that sends a joy-buzzing spark of life from one hand to another. Think of the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Or Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. People have always craved hand-to-hand physical contact. Art Fletcher’s heir as the Yankees’ third base coach was Frank Crosetti, and when Mickey Mantle hit his 500th home run in 1967, Crosetti did something unusual. “[He] shook my hand today,” Mantle said. “It’s the first time in 500 homers he ever shook my hand. I remember in the ’64 Series, when I hit a homer off Barney Schultz to win a game, he ran down the baseline and patted me. But he never before shook my hand.” Mantle seemed to hold Crosetti’s handshake in greater reverence than his own milestone dinger. A handshake withheld—for years, or even a moment—has its own power.

Charles Barkley stripped himself of his Rockets captaincy for a single game in 1999 rather than do the pregame handshake at center court with his ex-teammate Scottie Pippen (by then a Trail Blazer), with whom he had publicly fallen out. In sports, such snubs are legion. Uniformed children snub international soccer stars in those pregame handshake lines in the Premier League. As Liverpool stars, Luis Suárez and Steven Gerrard both suffered this ignominy. Handshake snubs, as Barkley knew, were part of the whole telenovela that was the NBA in the ’80s and ’90s. The Celtics failed to shake the Pistons’ hands after being vanquished in the playoffs in ’88 … and the Pistons, in turn, didn’t shake the Bulls’ hands when Detroit was ushered off the playoff stage in ’91, as Michael Jordan recalled in The Last Dance. But Jordan himself didn’t shake Alonzo Mourning’s extended hand before tip-off of a Bulls-Heat playoff game in ’97. This daisy chain of prominent snubs, paradoxically, links these players’ hands through history. Six Degrees of Never Shakin’. All these famous American athletes, with their famous nonhandshakes, are the opposite of what the Grateful Dead had in mind when they sang, “Shake the hand that shook the hand of P.T. Barnum and Charlie Chan.”

Worse than the handshake withheld is the handshake offered and then withdrawn. Psych! Even worse than that, however, is the unrequited handshake. There are few sadder spectacles in sports than the middle-aged fan, hand hanging over the tunnel, who hopes in vain for a slap or a high five as NBA players retreat to their locker room. As these heroes disappear from view, and the arm dangles limply, that fan is literally left hangin’.

But those handshakes on the run can be hazardous in their own right. Steve Sax hit a game-winning homer in 1985, and as the Dodgers’ second baseman turned for home, third base coach Joe Amalfitano extended a palm in congratulations. The ensuing on-the-fly handshake broke Amalfitano’s right thumb. “From now on,” Amalfitano said, “I’ll just wave.” The next season, Rangers knuckleballer Charlie Hough injured himself attempting to shake hands with a friend. It was, he said, “an interlocking pinky shake,” the kind that seals a pinky promise, and it sent Hough to the operating room, where pins were implanted in the small finger of his right hand. Sometimes, a promise breaks you.

***

In 1975, three American astronauts and two Soviet cosmonauts linked their Apollo and Soyuz spacecrafts, then set about shaking hands 140 miles above Earth, a space dap that briefly united unfriendly superpowers. Back on Earth, the most famous meeting of hostile hands came in ’93, between PLO chairman Yasser Arafat and Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin. Egged on by President Bill Clinton, on the South Lawn of the White House, their mutual grasp remains renowned as the Oslo Handshake. That may sound like a euphemism for a violent act—like “Glasgow Kiss,” for a headbutt—but the Oslo Handshake was quite the opposite, ceremonially sealing an unprecedented (if ill-fated) peace accord that was first negotiated in Norway.

Sports have seen similar moments of peace brokered by handshake. Jim Thorpe shook hands with International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage in Los Angeles during a telethon to raise money for the 1952 Olympic team, 40 years after the IOC stripped Thorpe of his Olympic gold medals for having accepted $2 per game to play minor league baseball. If not quite the Oslo Handshake, this Hollywood Handshake was an indelible act of forgiveness from Thorpe, though such moments are not always staged, as this one literally was, in the El Capitan Theatre.

On May 8, 1979, Rangers pitcher Ed Farmer hit Royals outfielder Al Cowens in the face with a pitch, shattering Cowens’s jaw. A year later, Cowens (then playing for the Tigers) grounded out against Farmer (pitching for the White Sox) and ran to the mound instead of first base, tackling the reliever in what Chicago owner Bill Veeck called “a felonious assault.” Cowens was suspended for seven games, Farmer pressed charges, a warrant was issued in Illinois for Cowens’s arrest and he skipped the Tigers’ next road trip to Comiskey Park. But the following week, with the White Sox in Detroit, Farmer offered an olive branch, telling Detroit News columnist Joe Falls, who acted as a go-between, that he would drop the charges “if Cowens would offer his hand.” Before the next game, 16 months after the initial beanball, the two men exchanged lineup cards at home plate, along with something more significant: a handshake.

Farmer died this April; Cowens died in 2002. But both endure, joined at the hand, as a single example of burying the hatchet.

Of course, handshakes are frequently more significant to one party than to the other. A man and his young daughter approached Willie Mays as the retired outfielder ate breakfast in the coffee shop of the Bally’s hotel and casino in Atlantic City in 1980. “May I shake your hand?” the man asked, as the greatest baseball player in history tucked into his eggs with a reporter from The Washington Post. “And would you shake her hand too?” Without rising, Mays set down his fork and shook both hands, for he was at the time being paid $100,000 annually by the casino to shake hands, a testament to the human desire to grip, shake or otherwise touch the hand of greatness, as if that hand were a pump handle that might yield some wellspring of collateral charisma.

***

Guinness World Records claims that history’s longest handshake lasted 33 hours and three minutes, a feat jointly achieved in 2011 by two sets of competitive handshakers—a pair from Nepal and a pair from New Zealand—in Times Square. But that ignores the handshaking team of Minnie and Paul, two cartoon baseball players who often appear on the Minnesota Twins’ sleeve patches, and who have been greeting one another across the Mississippi River with a perma-shake since 1961. The enormous likeness of that logo at Target Field—electrified and 46 feet tall—is perhaps the largest representation in the world of two people shaking hands. When a Twins player hits a home run, Minnie and Paul light up in neon, and this summer it will be a happy symbol—if only on television, without fans in the stands—in a metropolis consumed by grief and strife after the police killing of George Floyd. In response, Nascar’s only black driver, Bubba Wallace, had a handshake painted on the hood of his Chevrolet: a black hand and white hand clasping.

Saint Paul illustrator Ray Barton was paid $15 for his Minnie and Paul logo in 1961. A half century later, when the Twins moved into Target Field in downtown Minneapolis, the brand-new Minnie and Paul sign was animated for a TV commercial in which the pair, through the magic of CGI, briefly broke their handshake to dap each other up with forearm bashes, fist bumps, soul shakes, bro hugs, chest bumps and manifold other forms of nonverbal greeting before returning to their familiar grip and grin.

But even that handshake has not endured as long as the one between two other baseball men who were last teammates more than 60 years ago. In his later years, George Shuba visited schools, speaking to children about their shared humanity while handing out prints of himself and Jackie Robinson shaking hands. “He really enjoyed doing that,” says Mike Shuba, who accompanied his father all over North America, spreading the gospel of the handshake. “And maybe his message stuck in the heads of a few youngsters over the years.”

Next April 18, on the 75th anniversary of that historic handshake, a statue will be unveiled in Youngstown by the acclaimed sculptor Marc Mellon, whose other subjects include Walt Whitman, the poet who identified in “Song of Myself” as a “comrade of all who shake hands.”

Once installed downtown, in Wean Park, Mellon’s seven-foot statue of Robinson and Shuba shaking hands at home plate might serve as a tombstone for the handshake itself, a bronze memorial to a fading custom. But the statue is also meant to look forward—a handshake of Hello, not Farewell. “I hope it’s a corrective to what’s going on in the world right now,” says Mike Shuba. “It’s not so important to look back on that moment, but to inspire people to do great things.” In that way, the handshake will live on as a metaphor, an open invitation to join hands.

Read more of SI's Daily Covers stories here