A story from the Great Beyond.

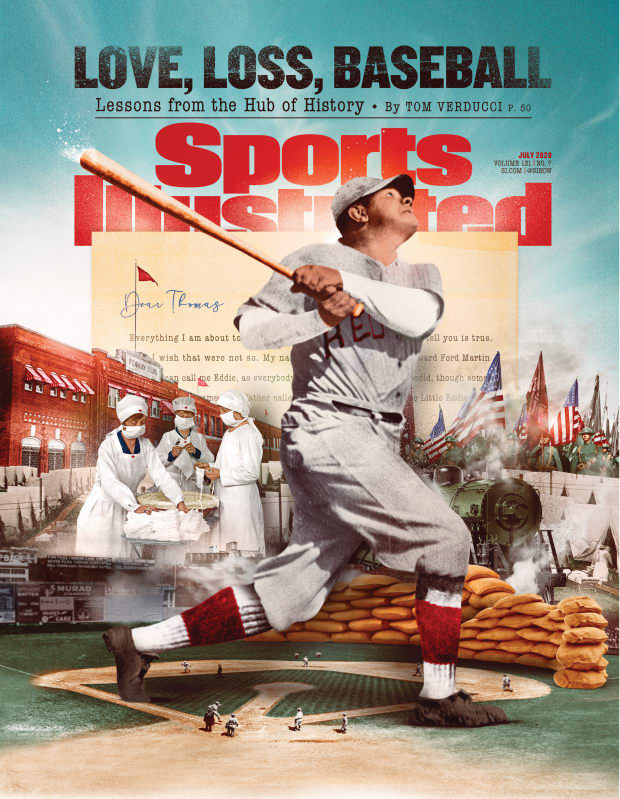

Editor's note: When the world went into quarantine, most of us began to fixate on the uncertainties of the future. Senior writer Tom Verducci took a different tack. He started digging through the past in search of a story that would resonate in what felt like a time of unprecedented chaos. “The usual nuts and bolts of baseball coverage seemed so trivial,” Verducci says. “I knew that to find something meaningful to write about required at least the backdrop of the pandemic.”

Verducci was aware that Silk O’Loughlin, a well-known American League umpire in the early decades of the 20th century, had died during the worldwide influenza outbreak of 1918. But while researching what he thought would be a feature on the umpire, Verducci stumbled upon the story of one of his baseball writing forebears: Eddie Martin, who covered the Red Sox for The Boston Globe from 1915 to 1918. Martin chronicled life at the center of the sports universe. The Red Sox, winners of four world championships between 1912 and ’18, were the most glamorous franchise in the country’s favorite sport. And in 1918 their best pitcher, a charismatic young lefty by the name of Babe Ruth, was turning himself into a slugging phenomenon, singlehandedly reinventing the sport and what it meant to be an American celebrity.

Of course there were darker historical currents flowing through 1918, and as it all coalesced in his research—a global pandemic, a world war, baseball celebrity, Martin’s personal story of love and tragedy—Verducci saw the makings of more than a simple feature. “Letters From the Hub” reads like a novella, but aside from Verducci’s epistolary literary device every bit of it is true. “I was blown away by the similarities between what a frightened public faced in 1918 and what we are facing in 2020,” Verducci says. “In the end, this is a timeless story. It is a love story. It is a story about how the random, evil nature of a pandemic makes us cherish even more the sweetness of small moments and those we love.”

Click here to learn more about the story behind Letters From the Hub. Click here to read chapters VI - IX of Letters From the Hub, and click here to read the final chapters.

Dear Thomas,

Everything I am about to tell you is true. I wish that were not so.

My name is Edward Ford Martin Jr. You can call me Eddie, as everybody else did, though some who knew my namesake father called me Little Eddie. Given that I was born in 1884, it should come as no surprise that I am writing to you from the Great Beyond.

Discretion and wisdom prevent me, even as a writer, to begin any modest attempt to describe this place after life. Suffice to say, as with love, Yeats and sunsets, the moment you try to elucidate the ethereal is the moment you diminish it.

Rather, I am here as a fellow baseball writer to tell you a most important story that you must hear in your time of suffering and sacrifice. I lived during the worst pandemic in the history of humankind: the influenza pandemic of 1918. It struck one-third of the world’s population and killed between 50 million and 100 million people, including 675,000 in the United States. Boston, my home, was the early epicenter.

So vicious was this killer virus that healthy, vigorous young people suddenly dropped in the street and were dead within as few as 12 hours. Horrible is too kind a term. It announced its lethalness when a victim turned a bluish purple, or “huckleberry” as we called it. Pneumonia blocked oxygen from entering the blood. The lungs filled with so much blood that upon autopsy the lungs sank like stones when placed in water.

When 1918 began, life expectancy for Americans was 54 years for women and 48 for men. By the end of the year the influenza pandemic had reduced that life expectancy by 12 years.

The reason I must write you is because I see so many similarities in what we experienced and what you are experiencing now. You need to know the arc of a pandemic, as well as the role of baseball in a society when fear, death and the unknown are constant companions. And you need to hear it from someone who was in the middle of it all.

Like you, in failing to understand how this pandemic began, we were guilty of creating irrational conspiracies to give some shape to a massive mystery. Considering we were at war against the Kaiser, some people thought the virus was delivered by gas clouds released by German U-Boats. Some said the virus was slipped into aspirin tablets made by Bayer, a German company. A politician in Colorado blamed Italian immigrants.

Like you, we had no idea when it would end.

Like you, we were late to quarantine and quick to reemerge.

Like you, we wrestled with the “essentialness” of baseball.

You undoubtedly noticed I have chosen the form of a letter. It is because the epistolary method was one of my favorite literary devices as a Red Sox beat writer for The Boston Globe. Often when filing a dispatch from spring training, I would arrange my story in the form of a letter to a friend back home. Instead of a byline, my name would appear at the bottom, flush right, in the manner of the valediction: “With Every Good Wish, Edward F. Martin.”

Back in 1858, the great writer Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to the Boston State House as “the hub of the solar system,” such was its physical grandeur and civic importance. A great line like that becomes literary taffy: It never gets old but is easily stretched. So it was with Holmes’s observation. The entire city of Boston soon became known as “the hub of the universe,” in a not always complimentary commentary on what Bostonians thought of themselves. Eventually it was shortened to simply “The Hub.”

Without the slightest bit of exaggeration or immodesty I tell you that in 1918 I stood in the hub of the entire sporting world. Entering the 1918 season, the Boston Red Sox and Boston Braves had won five of the previous seven World’s Series (as we knew it then). Baseball was king in America, especially in Boston. As many as eight newspapers competed for readers’ attention in the first two decades of the century. At dusk, boys wearing their tweed newsboy caps and shouting out headlines would hawk their evening editions on the street corners as men and women made their way home from factories and offices. To sell the papers the boys always gave alerts on two subjects: how we were doing in The Great War and how the Red Sox did that afternoon.

It wasn’t just that they won the World’s Series in 1912, 1915 and 1916 and their owner, Harry Frazee, a theatre impresario, was desperate to win it back. Their appeal also had much to do with a fellow named George Herman Ruth.

Babe Ruth had been one of the game’s best pitchers, but 1918 was the year he became a two-way sensation and, to borrow from the glossary of your times, the first true superstar the sporting world had ever seen. He was 23 years old and every bit the devil-may-care jovial rascal you imagine. Covering the Babe each day began only after the last out.

I turned 34 years old in the spring of 1918. Life for me bloomed like the tulips and narcissus in Boston Common after a long, hard winter. This was my second full year on the Red Sox beat. I was covering the premier sports team in the country for the premier newspaper in Boston while riding trains, eating meals and doing my level best to stay out of trouble with the Babe.

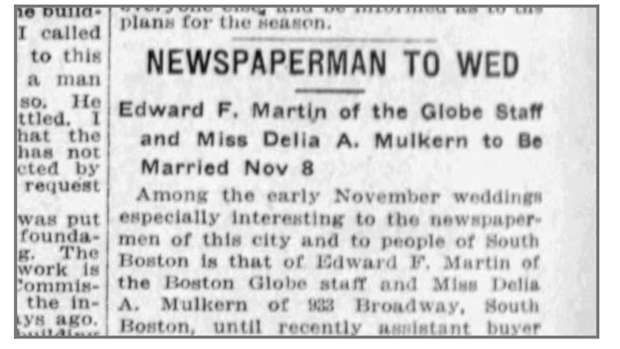

Better still, I also was deeply, madly in love. I had been married only 15 months earlier to the former Delia Agnes Mulkern. I knew it then and know for sure now because of whence I write: Her beauty was the most the good Lord permitted on Earth from His Eternal Kingdom.

Life could not have been better.

Until it could not have been darker.

With Deepest Regard,

Edward F. Martin

My Dear Thomas,

Before we go any further, I should tell you about myself. I am a Southie. South Boston through and through. I am a second-generation Irish American and part of a proud familial immigrant success story.

My grandfather, Jeremiah Martin, was born in 1813 in Garrettstown, County Cork, Ireland, a seaside village at the southern tip of the isle. As a young man who could neither read nor write, he left Ireland for New Brunswick, Canada. He eventually made his way to Brighton, Mass., before it was annexed by the city of Boston. There he married Eleanor Maguire, another Irish immigrant. Jeremiah was a salt-of-the-earth laborer. When he became a naturalized United States citizen in 1854, in place of a signature he simply drew an “X,” and the clerk noted “his mark.”

Jeremiah and Eleanor had three children. The youngest was my dad, Edward F. Martin Sr., who was born in 1850. Dad was born to be a fireman. He started as a lad with the famous Braintree Fire company and soon joined the Boston department, quickly working his way up from hoseman to foreman to captain.

After his first wife died of consumption, my father, at age 33 and the father of two boys, married Mary Ford in 1883. Their wedding reception was held at the home of the bride’s parents at 671 East Sixth Street in South Boston, where the newly married couple also would live. Owing to my father’s immense popularity, Boston fire commissioner John E. Fitzgerald and approximately 100 firemen attended. I still have no idea how they packed so many firemen into that two-bedroom house. But that’s how much my dad was beloved. At 7 p.m. that night, Edward and Mary left via the Fall River train line on their honeymoon: two weeks in New Jersey, New York and Brooklyn.

Four years later, I came along, with a first name from my father and a middle name from my mother. What I remember about my dad was an abundance of generosity and goodwill. A stout man with an impressive mustache that resembled the working end of a streetsweeper’s broom, he laughed easily and often. He loved his job. People were drawn to his good nature and wit. I am glad I received more from him than my first name.

I also remember his gold watch. In 1888, the year after I was born, Eddie retired as secretary of the Massachusetts State Firemen’s Association. They threw him a big party with lunch at Enghbert’s Café. Among the dignitaries was Fitzgerald. A tall, handsome man with a gift for public speaking, Fitzgerald was a big shot. By then he had been appointed by President Cleveland as tax collector for the state, the start to what would be an influential career in politics and public service.

It was an amazing life for someone who by all rights should have been dead. In February 1864, at the age of 19, Fitzgerald left Ireland as one of 200 Irish immigrants stuffed with cargo and mail in the steerage on the steamer Bohemian. Just off the coast of Maine on a foggy night, the ship smashed against Alden Rock. A hole tore open in the engine compartment. As the ship sank, some made it to lifeboats, others perished in the icy waters. By the time bodies stopped washing ashore two months later, the death toll was 42. Fitzgerald survived. He became a lawyer.

Fitzgerald watched proudly as they presented the gold watch to my father. I still remember that timepiece because in our humble house on East Sixth in South Boston it was the most exquisite thing I ever saw, standing out like a gold nugget in the black seam of a coal mine. It was a hunting-case pocket watch, the kind with a spring-loaded cover with the hinge at the nine o’clock position. It was made by the American Waltham Watch Company, an outfit on the Charles River that made the watch presented to Lincoln upon delivering the Gettysburg Address and the chronometers that kept most trains in America running safely and on time. Hooked to the watch was a massive gold chain with an enamel charm on the end. On one side of the charm was a depiction of a fire engine. One the other was his name and rank, captain.

One morning, a Monday in August of 1893, my father suddenly collapsed. They took him to City Hospital, where his body was seized in general paralysis. By 11:15 p.m., the captain of Boston Engine Company 18 and the strongest man I knew, was gone. The cause of death was listed as meningitis. He was only 43 years old.

I learned about death too early. I had to grow up fast. I was only nine years old.

***

We built schools back then not by low bidders cranking out giant boxes with comfortable student lounges. We built them the way the ancient Greeks built the Parthenon: massive, imposing structures and cultural landmarks meant by famed architects to inspire or even awe children like me.

My Parthenon was Lincoln Grammar School on Broadway, near K Street. Dedicated in 1859, it was designed by J.G.F. Bryant, who had just finished building the addition to the famed Boston State House, the hub of the solar system. Bryant designed a four-story building 93 feet in length topped by a Mansard roof and cupola. Atop the cupola stood a four-sided clock donated by Major Frederick Walker Lincoln, the edifice’s namesake.

Lincoln School was an eight-minute walk from my house on East Sixth Street, where I lived with my widowed grandmother; my widowed mother, who took a job as a bookkeeper; two cousins; and my older half-brother, James, who worked in the mail room at the Globe.

At 16, I worked after school as an optician, helping people with their eyeglass prescriptions, something of which I had first-hand knowledge. But through James, I found out that fall about work at the Globe. On November 16, 1900, I was hired for a month to work there in something called the vote counters’ room. The Globe ran these reader savings contests in which people submitted their savings coupons to the newspaper. Weekly winners might receive baseball gear for boys or cameras, hatpins and stickpins for the girls.

I must have been fairly accomplished at counting coupons because on January 1, 1901 the Globe hired me as a state house messenger. That was a thrill: Little Eddie from East Sixth Street in the hub of the solar system!

That fall another Parthenon opened. South Boston High School was the first high school built in South Boston and it made Lincoln look like a shack. It was designed by Herbert Dudley Hale, who was educated at Harvard and Ecole de Beux-Arts in Paris. Hale designed the four-story Colonial with an outline to resemble the White House, though his palette included ochre brick and Indiana limestone.

In September of 1901, as part of the initial class, I stood in front of South Boston High School with all the wonder and awe Hale must have sought. I might well have been staring up at one of the pyramids of Egypt. I climbed the 16 granite steps and pulled open one of the three giant double doors, revealing a huge, gleaming vestibule of white and Knoxville marble. At the center of the lobby was a mosaic that featured a lamp encircled by a laurel wreath of inland brass. Hale had succeeded. It made a young man dream big.

What really blew me away was a new innovation that could be found in every classroom: a telephone, each one connected to the main office.

My schooling days were coming to an end. After graduating from South Boston, in the fall of 1902 I took a full-time job with the Globe as a night clerk. I was 18 years old. In June of 1903 I was put on the city staff as a reporter. Because of my dad, it was said that every police and fire official in the city of Boston knew me, and I cannot contest that observation. The Globe noticed. At 19, I was permanently assigned to cover Fire Headquarters and Police Headquarters.

Besides covering the firemen, I was part of the fire department’s South Boston baseball team. I was the official scorer. We practiced at the Randolph Street Playground. We even traveled to New York to play firefighters there. After one big win over Dorchester Heights, we had a party planned for Hyde Park. But when it rained, we moved the party to my house. It ran from 4:30 p.m to midnight.

Other than fraternizing with my police and fire buddies, most of my social activity happened through the church. I was an officer with the Knights of Columbus and an active member of the young men’s sodality at St. Augustine’s Church.

On April 27, 1904, St. Augustine’s hosted a Leap Year Party in its hall on E Street. It was billed as a reunion for the girls’ sodality. The young men’s sodality and ushers’ club also were invited. “Dancing was begun promptly at 8,” reports said.

Miss Agnes Norris was floor director. I don’t remember Agnes, but I sure do remember one of her assistants. Even in a constellation of people in a crowded dance hall, Delia Mulkern stood out like a North Star. She was 17 years old. Her thick, dark hair was swept up elegantly. She moved gracefully, even theatrically. Indeed, three months earlier Delia had played the lead role as the interlocutor in the sodality’s annual stage production. She was “the queen of the farm” in a presentation billed as The Farmers’ Daughters’ Holiday.

I was smitten, though it would be years before we became a serious item. Delia also went to South Boston High School and was the daughter of two Irish immigrants. The Mulkerns lived on Mercer Street, about 10 blocks from me. Delia went to work as an assistant buyer in the infants’ shoe division of Filene’s department store.

My career at the Globe, meanwhile, was going great. The policemen and firemen were like my brothers. I joined the Holden Club, a social group of 25 men, mostly policemen, firemen, postal workers and newspapermen. We held banquets twice a year.

I was the police and fire reporter for 12 years. Then one day in the summer of 1915 Walter Barnes, the Globe sports editor, approached me with an idea.

“Eddie, how would you like to cover baseball?” he said. “You can write about the Red Sox.”

Barnes knew I loved baseball. In addition to being part of the South Boston firemen’s team I also played on the Knights of Columbus team. The Boston Braves were the defending World Series champions and the Boston Red Sox were in first place on their way to leading the American League in attendance and winning the next World’s Series (as we knew it then). The police and fire beats provided friends and satisfaction but being asked to be a baseball writer at the Globe was something else entirely. For a reporter who loved baseball it was the equivalent of a ballplayer not just being called up to the big leagues, but also given the chance to be a star.

Indeed, the very man I would be working with on the Red Sox beat was the Babe Ruth of baseball writing. At a time when legends such as Grantland Rice, Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon graced sports pages with their craft, nobody was more respected within baseball circles than the man they called “The Silver King,” Tim Murnane. I could not say “yes” fast enough.

Little did I know that the writing partnership of Little Eddie and the Silver King would come to a tragic end.

Yours in Baseball Writing,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Tom,

Barnes, my sports editor at the Globe, explained to me why he wanted me on baseball. Part of it was my training. By working the police and fire beats, I was expert at meeting deadlines, working quickly under duress and developing sources, all hallmarks of a good baseball writer. The friendly nature I inherited from my father, not just his friends around every firehouse in Boston, served me well in a profession with trust as its currency.

Barnes explained there was another component to his decision: Murnane was 64 years old. Barnes wanted to groom his replacement.

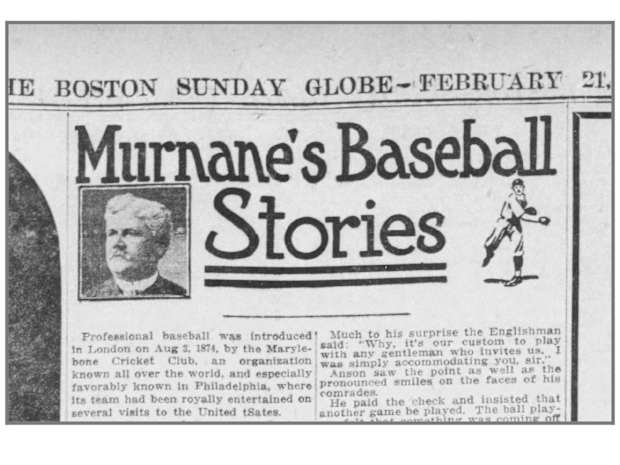

Tim Murnane was a giant, an impressive man by any measure. As he added weight in his later years on his 5-foot-9 frame, and as his thick, wavy head of hair turned brilliant white, and as he grew a bushy mustache that called more attention to the cleft in his chin, he looked regal, or to borrow a popular word from the times, like a magnate.

A first-generation Irish American, he was born Timothy Hayes Murnan in Connecticut, attended Holy Cross and played eight professional seasons, winding up with the 1884 Boston Reds of the Union Association as a player-manager. As a young man, clean-shaven and with his dark, wavy locks well combed, Murnane was stunningly handsome. He worked a bit as a scout. Then, in 1887, the Globe hired him as a baseball writer under a directive from publisher Charles H. Taylor to increase the paper’s baseball coverage.

At the suggestion of sports editor William D. Sullivan, himself an Irish American, he added an “e” to his byline (“Tim Murnane”), probably to appeal to non-Irish readers as well. In 1889 he switched to “T.H. Murnane,” which became the imprimatur of great baseball writing for the next three decades.

Murnane had it all. He wrote colorfully, knew the game inside and out, and enjoyed the respect of those in the game. He did not invent the Sunday notes column, but he certainly popularized it, first with “Murnane’s Gossip on the Game,” which became “Murnane’s Baseball Stories,” because he was, as you would say today, his own brand. He sold newspapers.

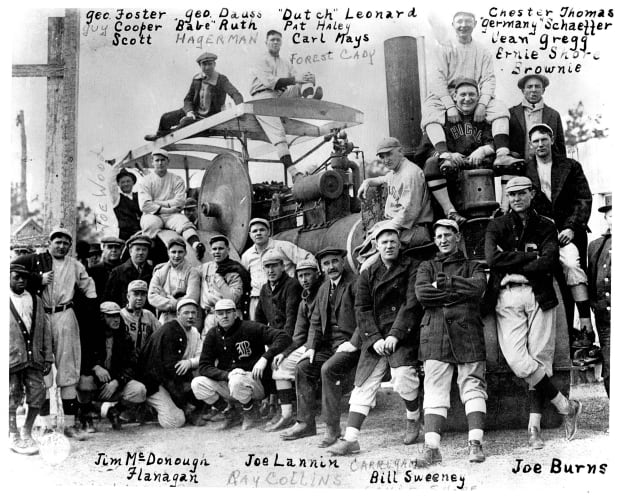

Most people followed baseball back then through newspapers. Murnane understood it was important to present ballplayers to them as fully formed and colorful people, not just a name and a batting average. He made them relatable. His copy was full of yarns and nicknames. I took notice. Influenced by the Silver King, my coverage of the 1918 Red Sox would keep readers up to date on the Babe, Stuffy, Slam, Doc, Heinie, Hack, King, Dutch, Sad Sam, Bullet Joe, Deacon, Hoop, Sub, Dapper Dan and the rest of the gang.

I joined the Silver King on the Red Sox beat starting with a doubleheader August 4, 1915 at Fenway Park against the Cleveland Indians. My first baseball story was about a rainout. Rain wiped out both games. I referred to the 37–57 Indians as the “Fohlies.” I could not take such license writing about two-alarm fires or horse thieves, but I enjoyed the wider berth of creativity baseball writing afforded.

I soon learned that being around the Silver King was like being in the presence of one of your rock stars today, only without the ego. Murnane knew everybody. Everybody knew him. With his charm and thick Irish brogue, he enthralled people. Watching Murnane around ballplayers reminded me of my dad around firemen. There was no hierarchy, no walls of pretension between them. They knew Tim treated them fairly.

The Globe once said, “Nobody ever saw a printed word by Tim Murnane that was violent, or in the nature of an attack.”

“After all,” Murnane would say, “they are human beings.”

Murnane lived at 12 Manchester Road in Brookline, a 3,100-square foot home with six bedrooms. When a Red Sox game ended at Fenway, Tim would pack up his belongings, walk the 1.5 miles home, and dictate his story to his daughter, who served as his personal assistant.

I would be rat-a-tat-tapping on my Underwood throughout the game, pounding the beast like a possessed percussionist. My job was to write what is called a “running” story, a detailed account done in close to real time so that it could make the evening edition. Sometimes, as with doubleheaders, the running story included only five innings from the game when my deadline hit.

Working next to the Silver King was a joy. Our parents had come from adjoining counties in Ireland. He liked to refer to himself in the third person as “the Old Scout.” He introduced me to his sources. On top of that the Red Sox won the World’s Series that year. How lucky was I? The Red Sox clinched the title with a 5-4 win in Game 5 in Philadelphia against the Phillies. I wrote a story about how the Red Sox players were eager to go to their respective homes rather than stick around Boston for a parade. Credit my observational skills honed on the police and fire beats for what I noticed after the last out: a grounder fielded by shortstop Everett Scott, who threw to first baseman Del Gainor.

I asked Gainor what happened to the baseball. He told me Ray Collins, a relief pitcher, wanted the ball and offered him $35 for it (the equivalent of $900 today). Gainor declined. That prompted Scott to claim 50 percent ownership, since he assisted on the final out, so he should have a say and split the proceeds 50-50. Gainor was having done of it. He kept the baseball. I wrote:

It is a 10-to-1 shot that every man, woman and child in Elkins, W. Va., where Gainor lives, will see the souvenir before the snow flies.

My lucky run continued. The Red Sox won the World’s Series again in 1916. Little Eddie and the Silver King were an honest-to-God team as perfectly aligned as tongue-and-groove construction. I would bang the keys with speed and alacrity on my running stories, always borrowing from what I learned from Murnane about using colorful words and phrasing the way a cook uses seasoning, and Tim would craft these next-day game stories that were so insightful you thought the game wasn’t really over until the Silver King explained it to you.

The great and wise Branch Rickey, then running the St. Louis Cardinals, paid Murnane the ultimate compliment: “He pictured a ball game so that the professional could see what had won and lost it.”

On October 13, 1916, the Red Sox beat Brooklyn in the clincher, 4–1, at Braves Field, not at Fenway Park, so as to accommodate the crowd of 43,620. The game took just one hour and 43 minutes, which allowed me a smidgen more time to craft my story for the evening edition. I knew during the game a huge crowd had filled the street in front of the Globe to follow the game. We called this area “Newspaper Row.” Reports would come in on the teletype. One man with a megaphone would announce it to the crowd. Another would update the runs, hits and outs on a big blackboard. In a write-through for the morning edition, I wrote:

When the last Brooklyn man was retired, there was a final cheer accompanied by the tooting of automobile horns somewhere on the outskirts of the crowd. And that final cheer had hardly died away before Globe newsboys with extras containing a detailed story of the game were dodging about the street and advertising their wares.

There was a real celebration about 4 p.m. yesterday in Newspaper Row.

Two seasons covering the Red Sox. Two World Series titles. Learning the trade from the great Tim Murnane. What could possibly be better?

Falling in love.

With Warmest Regard,

Edward F. Martin

Dearest Tom,

Fifteen days after the last out of the 1916 World’s Series, on October 28, I was walking Delia Mulkern back to her house. Moonlight sparkled in her eyes. We held hands. By then the Mulkerns had moved to a multi-family home at 933 East Broadway, in the City Point section of South Boston, which was only a 10-minute walk from my house on East Sixth. That beautiful young girl at the dance at St. Augustine’s, now 29, had agreed to be wife.

I opened the door and stepped aside to let her pass first. That’s when everybody yelled, “Surprise!”

Delia’s co-workers at Filene’s completely surprised us with an engagement shower. Her good friend, Miss Susie Dean, arranged it. Delia’s parents were there, as were my mom and grandmother, Mary Ford, now 86 years old and as the Globe referred to her, “well known as a pioneer resident of South Boston.”

Our wedding announcement appeared in the next day’s Globe. “Miss Mulkern,” they wrote, “has been very popular in social and church circles.”

We set the wedding for November 8, 1916 at 7 on a Wednesday night at St. Eulalia’s on the corner of O Street and Broadway. The church had been dedicated only 16 years earlier, built to accommodate the steady stream of Irish Catholics into South Boston.

We invited immediate families, relatives and a few friends to the wedding. Presiding was Rev. Jeremiah Driscoll, who at 34 years old was only two years my senior. Susie Dean served as Delia’s bridesmaid. I picked Francis H. Corrigan as my best man. Frankie lived on Farragut Road in the City Point section. I knew him since our days in grammar school at Lincoln. We stayed friends through the years. We were fellow members of the Knights of Columbus.

I loved Frankie because he was such a free spirit. This tells you what kind of a guy Frankie was: One day the company he worked for transferred him to its office in Lynn, Mass. Frankie surprised everybody by getting up early and walking to work—a 13-mile, four-hour hike one way. Why? Just because.

The world is an amazing place. It can heave and shake with frightening power. Earthquakes, tornadoes, tsunamis, thunderstorms, blizzards, avalanches, forest fires and the like. But I am convinced that there is nothing more powerful on God’s great Earth than something that can neither be measured or seen: the power of human emotion.

Sadly, I first was convinced of that at age nine, when without warning Dad was seized by apoplexy and died the same day. The depth of the pain I felt was deeper than the bottom of the ocean. Only through God’s grace did I also feel its inverse: the power of human emotion at the apex of happiness. That was the moment I turned my head to see my Delia walking down the aisle of St. Eulalia’s toward me with Father Driscoll at the altar.

I don’t even know what music played on the church organ. I only know that in my head I heard a chorus of angels and I nearly wept with joy right there. Not before or since did I see a more beautiful sight. Delia wore a grey satin dress embroidered with silver and trimmed with silver. She wore a hat with silver trim and beaver fur. She carried a bouquet of roses. Honestly, I don’t even remember what happened after that. I only remember thinking about Dad, and how much he would have loved Delia.

I am told I made it through the ceremony without passing out. I do remember that after the wedding our immediate families and relatives joined us at the Mulkerns’ house for the reception. At midnight, Delia and I said goodbye to everyone and left on our honeymoon: to New York, Atlantic City and Washington.

When we returned, we moved into a house at 1748 Columbia Road. It was a multi-family home built in 1910, right across the street from M Street Beach with a view of water. I timed the walking distances: five minutes to my mother, 11 minutes to Delia’s parents. Southies we were, through and through.

We celebrated our first Christmas as husband and wife in that house and rang in 1917. Only five weeks later, the telephone rang. Not since my father died was I so blindsided by such terrible news.

***

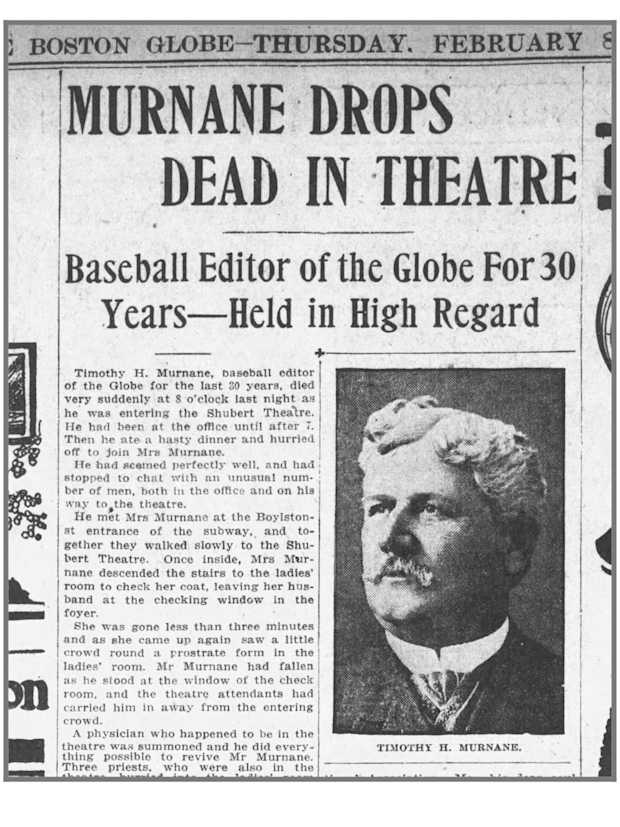

On February 8, 1917, Tim Murnane put in a full day of work at the Globe’s offices. The start of spring training, and his 31st season as a baseball writer, was only one month away. Murnane left the Globe a little after 7 p.m., hastily ate dinner, and rushed to join his wife, Agnes May, for a performance of Eileen, an Irish operetta, at the Schubert Theatre.

They met at the Boylston entrance to the subway. They walked slowly to the theatre. The white of Tim’s mustache and locks seemed especially striking against his black topcoat and black bowler. Once inside the foyer, Tim queued at the checking window while Agnes May excused herself to check her coat down one flight of stairs. It was 8 p.m. She was gone two minutes—three minutes, tops. When she returned to the foyer, she saw a small crowd around a white-haired man on the ground in the ladies room. It was Tim.

He had dropped suddenly. Theatre attendants had carried him away from the entering crowd and into the ladies room. Three doctors and a priest responded quickly.

“Raise his head!” someone implored.

“It is too late to raise his head,” one of the physicians said softly. “He is gone.”

The Silver King was dead, struck down by a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 65 years old.

The death of Tim Murnane was Page 1 news in the morning Globe: Murnane Drops Dead in Theatre.

Shock and sadness enveloped the baseball world. So respected and authoritative had Murnane been that it was hard to imagine baseball without him. Tributes poured in immediately. Clark Griffith, manager of the Washington Senators, said, “He has been the grand old man of baseball. He was the greatest writer in the game. He has done more to uplift the game than any other man who handled a pen.”

The Globe story, compiled by several writers and editors without a byline, gave the most fitting tribute:

He loved his home with an intensity that was beautiful to watch; he loved the Globe; he loved baseball. He lived baseball. When he talked with his friends his very gestures threw a ball or swung a bat. He saw the need of insistence on clean, high standards, and to him in a great measure can be given credit for building the greatest National sport in all history.

Two days later, I was assigned to write the story of the funeral and burial of Silver King. The proceedings were no less grand than if a head of state had passed away. The funeral cortege left the Murnane home at 12 Manchester in Brookline at 9:30 a.m. and rolled slowly through the five blocks to St. Aidan’s Church, his beloved parish, where a nephew of his presided over the high mass. Murnane’s casket was covered in a blanket of violets and sweet peas sent by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee. Among the pallbearers were the mayor, the district attorney, a congressman and several Globe staffers, including Walter Barnes, the sports editor. The church was packed with heavyweights from baseball, including future Hall of Famers Rabbit Maranville, Johnny Evers and Babe Ruth.

Seeing the Babe at Murnane’s funeral mass reminded of a great line from Tim to the Babe one day at the previous World’s Series. Silver King smiled and nodded at the Babe and said proudly, “Here we are. One big guy covering another.”

I almost cried when during the offertory two soloists performed the Recordare from Verdi’s Requiem, as beautiful and moving a goodbye as ever has been set to music.

At Old Dorchester Cemetery in 15-degree chill amid a blanket of snow, we pulled our topcoat collars tight against our necks as they lowered Silver King into the ground. My heart ached as I caught a glimpse of Agnes May and their four children. Seven months later, the greatest ballplayers in the world would volunteer to play a benefit game at Fenway Park to support Tim’s family. The Babe pitched for the Red Sox against an All-Star team that included an outfield of Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker and Shoeless Joe Jackson. Entertainers included Fanny Bryce, the Ziegfeld Follies, boxing champion John L. Sullivan and Will Rogers. The players also held a skills competition. The Babe won the fungo hitting contest, swatting a ball 402 2/3 feet.

The event raised $13,000, the equivalent of $262,000 today.

After the last prayer was said, I walked back to the Globe office and sat down at my Underwood. I stared at the keys. I took a deep breath. After the moving ceremonies, the time had come for me to say goodbye to the Silver King, my mentor. I began to type for the evening edition:

Tenderly and beautifully the last tributes of love and respect were today paid to the memory of Timothy Hayes Murnane, for more than 30 years the baseball editor of the Globe, the dean of all baseball writers, and affectionately known among baseball men as ‘The Silver King.’

Men of every walk of life came to pay their last respects today to the ‘Silver King’ before he was laid away in snowclad Old Dorchester Cemetery.

The services were just as ‘Tim,’ who always stood for simplicity, would have had it had death not come to him without any warning. Beautiful and impressive as they were, there was still a simplicity about them.

I hope I made the Silver King proud. Two weeks from turning 33, I suddenly felt a lot older. The two greatest mentors in my life, Dad and Murnane, were gone, each one taken without warning. I knew Tim’s passing meant a greater responsibility for me. I now was the lead writer on the Red Sox, beginning with spring training.

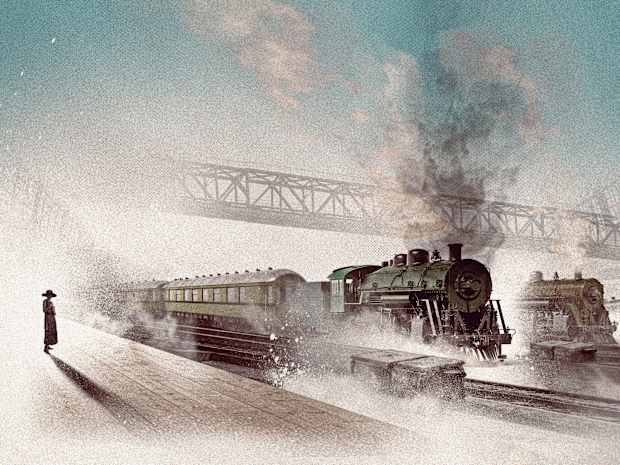

On Saturday March 3, I kissed Delia goodbye, told her I would see her in a month, and headed to South Station to catch a 2 p.m. Red Sox private train heading west toward Hot Springs, Ark., or as we scribes liked to call it, the Vapor Valley. We were scheduled to arrive Monday morning.

Only three players boarded in Boston, but we would pick up many others along the way. In Worcester we picked up manager Jack Barry, his wife and two friends, as well as Babe Ruth and his wife, Helen. In Albany, N.Y., we picked up Frazee and several more ballplayers, including William Devine, 24, a catcher and the son of a railroad brakeman from Albany. Known for his feistiness, Devine would later play under the name he used as a young boxer, Mickey Devine, but around us the hard-headed catcher answered to one of the last nicknames ever bestowed by Murnane when the Red Sox signed him that winter: “Skull” Devine.

Upon boarding the train, and unfamiliar with the traveling party, Skull took a seat by himself in the back of the car. I noticed Ruth stand up and walk back to the kid. The Babe introduced himself (as if anybody alive in 1917 did not know Babe Ruth), and said, “Come with me.” He introduced Devine to every member of the traveling party and invited him to sit with us. It is still one of the most gracious gestures I have seen from a ballplayer, especially from one as popular as Ruth. I asked the Babe what prompted his magnanimousness.

“Eddie, I sat in a corner alone on the way to the training camp when I broke in,” the Babe said, “and I don’t want to see another fellow doing it.”

We spent a few weeks in Hot Springs before embarking on a slow tour back home with many stops along the way to play exhibition games, mostly against the Brooklyn Robins. On April 1 it was so cold and wet in St. Louis that the game was scrapped. The postponement prompted Ruth to issue a challenge to one and all on the team to take him up in a round of golf. His bravado quickly dissipated when just about everyone told him he was nuts and would develop pneumonia if he hit the links in such weather.

After the postponement we boarded an overnight train to Davenport, Iowa, where the Red Sox and Robins were scheduled to try again the next day. Ruth continued to be a constant source of amusement, this time for his poetry, which included an homage to the two umpires working the barnstorming games:

“We are getting the Double O every day,

They are two splendid fellows, Silk and Hank.

I mean O’Laughlin and O’Day.”

I published the ditty in my report, accompanied by a line of my own: “Babe left his poet’s license at home.”

That same day in Davenport, however, took a somber turn for all of us able-bodied men. President Woodrow Wilson stepped before a special session of Congress and asked for a declaration of war against the German Empire.

Most Sincerely,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Tom,

At midday on March 9, 1918, I stood on a platform at South Station preparing to embark on my second spring training assignment. So much had changed in a year. I was more confident with a season on the beat under my belt. The Red Sox no longer were champions, having lost the 1917 pennant.

What’s more, as I stood there that day the world was a tinderbox, and sparks were everywhere around us. With Russia having fallen, the Kaiser had an open route to attack India in what the United States saw as a colossal plan to conquer all of Asia.

The War Department said it would stop issuing daily casualty lists of American troops in France, for fear such dark news was abetting the enemy. The death toll just among Harvard students and alumni reached 58.

The American front in Toul was taking on heavy artillery firing.

Two German fighter planes, aided by the Northern Lights on a moonless night, bombed London, killing 11 and wounding 46.

Thirty thousand letters from U.S. servicemen to their loved ones back home sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean with the RMS Andania, a British cargo ship hit by a German U-boat off the coast of Northern Ireland in January.

The draft act was amended to induct slackers immediately into military service, forgoing the usual due process of trial and jail time.

A bomb exploded at the new Woods Theatre in Chicago, where an anti-German play was days away from opening; police speculated German sympathizers were responsible.

So much mayhem. All of it fit within the 12 pages of the morning Globe tucked underneath my left arm as I waited for the 12:30 p.m. getaway train to Eden, more commonly known as Hot Springs.

Four days earlier, I gained a second responsibility: official scorer for Red Sox games.

“Congratulations each way are in order,” the Globe wrote, “and the job is going to be well taken care of, too.”

That same day I wrote the last of my “Stove League Embers” columns, the ones that pulled us through those four fallow months without baseball between the last game of the World’s Series and the train to Hot Springs. Of course, I made sure to include a note about the Babe:

Babe Ruth is dusting off his niblicks, midirons, drivers, etc. and says he’ll be goshdarned if anybody is going to stymie him in 1918. . . . He says he is going to win 30 ball games this year, too.

Ruth won 24 games the previous season and led the league by completing 35 of his 38 starts. But the Red Sox did not win a third straight World Series. With a 26–8 run to the finish, Shoeless Joe Jackson’s White Sox pulled away from the Red Sox to win the league.

The Boston manager, Jack Barry, joined the Naval Reserve after the 1917 season. To replace him for 1918, Frazee hired Ed Barrow, the team’s third manager in three seasons, and the rare manager who had never played a day of professional baseball. Like Connie Mack and George Stallings, Barrow managed in a suit and tie, though do not mistake his wardrobe as being indicative of genteelness. Barrow was a hot-tempered, bushy-browed, broad-shouldered gruff.

We boarded the train in our usual happy menagerie of newspaper men, photographers, cartoonists and Red Sox staffers. Only two players boarded with us in Boston: Babe Ruth, who lived on a farm in Sudbury, where Helen thought chopping wood and hunting would keep him away from the temptations of the city, and Dan Howley, who lived in Weymouth.

The best way to describe Howley is as the early 20th century version of David Ross. Howley was a 32-year-old backup catcher who served as a de facto coach. Indeed, Howley that year would wind up managing the Toronto Maple Leafs to the International League championship. The Toronto Star described him as “a big upstanding Irishman with a booming voice and inexhaustible fund of anecdote.” He later would become a big league manager with the Browns and Reds.

Howley’s entire big league playing career consisted of 26 games with the Phillies in 1913. He hit .125. But teams wanted Howley around for his baseball I.Q. and convivial nature. He had the gift of being able to get on players with clever one-liners and still be likable. Howley had what today you would call “clubhouse presence.” Everybody called him “Dapper Dan,” though it was not because of any sartorial splendor. Balding and fleshy-faced, Howley was the spitting image of “Dapper Dan” Hogan, a mob boss at the time in St. Paul.

Howley had another role with the team: keep Ruth in line. To the surprise of no one, when Frazee and Barrow announced the roommate pairings for Hot Springs, Howley and Ruth were paired.

As in past years, the train to Hot Springs would pick up more members of the Red Sox delegation along the way. Frazee and Barrow would come aboard in Albany. Until then, leaving Boston on a cold winter’s day, we were entertained by the comedy team of Dapper Dan and the Babe.

Babe Ruth will bring along his complete golf equipment and between here and Albany Dan Howley expects to obtain a very clear inside knowledge of the old game from the Oriole boy. No arrangements have been made for any golf matches on the train, but it is understood that there may be other games played.

The spring training itinerary was similar to the tour of 1917: three weeks in Hot Springs followed by a three-week barnstorming tour that would take us back to Boston for the April 15 opener. Within the first few days of training camp, two things were obvious: The team was loaded, and Babe Ruth was the most powerful hitter anybody had ever seen. To that point Ruth never had played anywhere else on the field than the mound, where he won 24 games in 1917. He was getting about 130 at bats a year as a pitcher. He hit .302 with nine home runs in that limited role over three years.

In 1918, home runs simply were not a common part of professional baseball. Gavvy Cravath and Dave Robertson led the majors the previous season with 12. There were more than three times as many triples than circuit clouts in 1917. Fans got to see a home run on average only once every three or four games.

In Hot Springs, Ruth kept launching towering fly balls over the fence in batting practice. It was as astonishing to see as what a flying machine in the air over Kitty Hawk must have looked like 15 years earlier. Everyone but Frazee was completely transfixed by the power show. A baseball in 1918 cost about $1.65. On March 18, after the Babe launched yet another one out of sight, Frazee called out to him, “That makes $9.90 worth of baseballs you have lost on me, Babe.”

Ruth turned to Frazee, smiled at his boss, and said, “Can’t help it. It appears to me as if they have got to make these ball parks larger.”

Ruth treated me great. The Babe wanted only to have a good time, and he wanted everybody else in on his fun. At 6-foot-2, 200 pounds then, he was one of the bigger ballplayers, even physically imposing. But there was this gentleness and boyishness about him that made you want to be in his company. He reminded me of Frank Corrigan, the best man at my wedding, who was known for walking 13 miles to work one day for no apparent reason. When the rest of the world asks, “Why?”, the Babe and Frank ask, “Why not?”

Two days after Frazee alerted Ruth to the financial cost of his hitting prowess, Ruth was standing in the outfield during practice when he signaled for me to come over to him. When I got there, he removed his wool sweater, handed it to me and said, “Hey, Eddie. Can you carry this in for me?”

With some other players I might have been insulted. This was the Babe. It meant I got a laugh out of it, as well as a line for my column:

“Where do you get that stuff,” said the scribe, who gave himself a thorough looking over just to make sure he was not wearing a bellhop’s uniform.

Four days later, on March 24, the Red Sox played the Robins in Hot Springs. Ruth, who was scheduled to pitch in relief of Carl Mays, started the game in right field. With the bases loaded in the third inning, Brooklyn pitcher Al Mamaux challenged Ruth. By now all of us are familiar with the legend of the mighty Babe Ruth and how his swing and his power changed the game. The birth of that legend arrived with the next pitch. We could not believe it was possible for a baseball to be hit so far until we saw it.

Ruth hammered out a circuit smash which every ball player in the park said was the longest drive they had ever seen. The ball not only cleared the rightfield wall, but stayed up, soaring over the street and a wide duck pond, finally finding a resting place for itself in a nook in the Ozark hills.

Had Ruth made the drive in Boston it might have cleared the bleachers in right center. As he was rounding first he said, “I would have liked to have got a better hold on that one.”

Ruth and baseball would never be the same. People were still talking about the home run the next day, as they would for years. The gruff Barrow smiled, knowing he had an honest-to-goodness sensation on his hands.

“I know how to write a ticket on that fellow now,” Barrow said. “He may say that he is Babe Ruth, but I have another name for him. He is John J. Production or I miss my guess.”

Said Johnny Evers, who had joined Boston as a player-coach and had been in professional ball for 17 years, “I never saw a player that could send it on the journey that Babe does, and never did I see any student smash them so hard.”

How lucky was I? Ruth was a baseball writer’s delight. The only way to see the Babe swing the bat then was to go the ballpark or catch a newsreel. Few people went to the ballpark, especially during war times. Average attendance in 1918 was 3,013. That’s it. Thanks to what Murnane taught me, I knew most people “saw” Babe Ruth through the word pictures we banged out on our Underwoods. I went to work:

It is the opinion of veteran baseball veterans like Barrow, Billy Murray, Johnny Evers and others that no man in the history of the game ever hit the ball any harder than the Oriole sharpshooter.

The ball Ruth hit off Mamaux may still be going yet.

It is the belief of many that at an early date Ruth will win a place among the greatest attractions in the game. They will go out to see Babe Ruth just as now they flock to lamp Cobb, Speaker, Walter Johnson and Grover Alexander.

To the Brooklyn players Ruth is a marvel, and the same goes for the fans here and over in Little Rock. Saturday when he was dropping balls over the fence at the Camp Pike diamond, his name was on every lip, and yesterday when the Yanigans [a term of the era for second-stringers] showed up to play there the big question of the day was, “Where is Babe?”

Every day in Hot Springs, Ruth put on a show. Then he would repair to Oaklawn, the horse-racing track with a glass-enclosed heated grandstand designed in 1904 by Zachary Taylor Davis, the same architect who designed Wrigley Field, then only four years old. To my surprise, it left Ruth little time for golf.

Babe Ruth might just as well have left those golf sticks out at Bellevue. He has not had any use for them since he came down here. . . . Instead of that he has devoted his afternoons to the ponies, and the golf clubs are just where he tossed them upon his arrival—in a corner.

Using my favorite literary device, on March 27 I filed my column in the form of a letter to my friend Charles Smith in Medford, Mass. When I read it again now I remember how happy I was to have such an incredible job.

Seriously, Mr. Smith, the Sox look like a swell ball club. I would supply you with facts and figures that would send this assertion right over the top only I am off figures. They bore me and I am down here having little rest and do not wish to be reminded of one of my regular home stunts—counting my money.

I call all the players by their front names, ride in the same cars with them, eat at the same table and enjoy many other thrilling privileges. I used to know all of the firemen and policemen once.

We are going over to Little Rock, the City of Roses, today—and, Mr. Smith, if anybody tells you this is not a great life he is terribly misrepresenting things. I could write you much more, but you probably know what a laugh you can get out of brevity.

I signed that missive “Maddeningly seriously yours.”

On April 2, I wrote to one of my firefighter friends James P. Maloney, the manager of the department’s baseball team. We were in Dallas, our third stop after leaving Hot Springs on our long Southern trip. There were 60 of us in the Red Sox traveling party. We filled two private train cars, with the overflow consigned to a third, public car.

Traveling with the ball club you get the hit and run sign for eats on the days that you have to. Rush from the park to the telegraph office and from there to the one-arm lunch and then to the rattler.

Some of us had to ride in the uppers last night. It was a crying shame, Jim.

Riding the “rattler,” as we called the train car, with the Red Sox was a rolling good time. On the way to Dallas, at 3 in the morning, one of the Red Sox players came through the car in which a bunch of us sportswriters were sleeping and loudly announced, “It is three o’clock!”

Somebody grumbled, “What of it?”

“Well,” came the reply, “I don’t want to have you fellows thinking that you don’t know everything that is going on around here.”

When we weren’t sleeping on the rattler, we were playing cards. The Babe liked playing hearts, especially when he was the score keeper. One night the other players got so fed up with his version of keeping score that they insisted that Harry Hooper replace him.

They had to call in an auditor after Babe Ruth officiates as score keeper in a hearts game.

“Here is where Harry’s luck turns,” Ruth said.”

The South was bone dry, which meant certain nonalcoholic beverages replaced the usual rivers of beer the traveling party preferred.

“What do you think of that stuff?” I asked one of the players.

“It is just like kissing your wife—no kick to it.”

I shall not mention the critic’s name.

We left Dallas at nine in the morning for a three-hour rattler ride to Waco, disembarked, played a game at 6:15 p.m. and boarded a midnight train for Austin with an arrival time at 3:40 a.m. From Austin we left for Houston and from Houston we continued to New Orleans. Nearly every day the Red Sox would pound the Robins. They looked better and better. In the spirit of Silver King, I decided they needed a nickname.

Inasmuch as the Robins were once known as the Superbas, it has been suggested that this outfit be called The Supersox, or if that is not satisfactory the Sox Soupers.

The Globe began using “Supersox” in headlines.

From New Orleans we continued to Mobile, where the wonderful pitcher Sad Sam Jones had a question. Jones was a wonderful pitcher with a baffling delivery and the most inapt nickname in baseball history. Apparently, a gentleman new to the sportswriting business, and from a distant press box vantage point, upon first impression found Jones to be especially serious while tending to his work on the mound. The writer called him “Sad Sam The Cemetery Man.” Sam actually was a sweetheart of a fellow with a tremendous smile he deployed often.

Sad Sam literally was an afterthought on the 1918 Red Sox. Frazee never sent him a contract for the season. He thought Sam was in the Army, one of 60,000 men at the Camp Sherman cantonment in Chillicothe, Ohio.

It turned out that Sad Sam was not in Camp Sherman but was home in Woodsfield, Ohio., still waiting for a contract from Frazee. About the time we left Hot Springs on our Southern trip he wrote a letter to Frazee.

“Forgotten me?” he wrote. “I’m not worth a contract of any sort? If I am through, let me in on it.”

Frazee quickly wired Sad Sam to quickly join the team.

Jones was with us for about 10 days when he posed a question to me in Mobile.

“Why don’t they send some of those Boston papers down to us, Eddie?” he asked.

“Well,” I told him, “we will just run around town and see if we can’t dig up some for you, Sam. Now, if you want your laundry taken out or your hair combed, just speak up.”

When you ride the rattler, eat meals, play cards and spend every day with the ball players, needling someone like that was perfectly acceptable, if not encouraged.

These exhibition games were events in each town. In Chattanooga, we pulled in two hours late, but that mattered little to the townsfolk who were thrilled to see us. The Red Sox marched up Main Street to a cheering crowd. Johnny Evers marched while carrying the Babe’s golf bag.

“I’m his caddy,” Evers said.

He was only half-joking. Frazee and Barrow had arranged new roommate assignments for the Southern swing. The job of keeping an eye on Babe passed from Dapper Dan to Evers, who was 36, was more of a coach than a player, and who was known as “The Human Crab” both for the way he fielded grounders and for his combative temperament.

The Red Sox were scheduled to play a doubleheader in Chattanooga, but the games were canceled because of the weather. It was so brutally cold that it was the first day since training began a month ago that the boys did not manage even a practice. We boarded an 11:05 p.m. train bound for Boston—by way of Cincinnati, Cleveland, Buffalo, Troy and Albany—with a scheduled arrival in Boston 37 hours later.

Back in Dallas, a porter named Alfred Robinson had joined our party. The boys slipped him a tip every day as the train needed to be loaded and unloaded regularly. But as we neared the end of the journey the guys decided to do something special for him. They summoned him to one of the cars and handed him a fat roll of money: $25 (a not insufficient sum equal to about $425 in today’s money), all in ones. Al broke out in dance.

But then Sad Sam Jones took the roll back, stuck it in his pocket and said, “Actually, Al, we are going to get you a gold-headed cane.”

This time Al wasn’t dancing.

Perplexed, he said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do with a walking stick.”

The train continued on. Just before we pulled into Boston, the boys summoned Al again. This time they handed him the wad of money and told him to keep it. Al was flabbergasted.

“I want to say something big to you boys,” he said in his most sincere tone, “and I can only think of one thing.”

He paused.

“Elephant! And that is what I will say to you.”

On these journeys I would type my stories on the rattler and upon stopovers find a telegraph office to transmit them back to the Globe. I took great delight in using the dateline below:

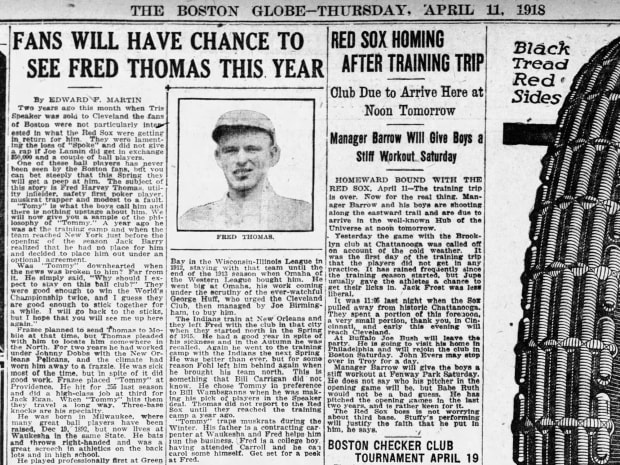

HOMEWARD BOUND WITH THE RED SOX, April 11 – The training trip is over. Now for the real thing. Manager Barrow and his boys are shooting along the eastward trail and are due to arrive in the well-known Hub of the Universe at noon tomorrow.

The Hub of the Universe. I love Boston. Do not get me wrong. But when the train pulled into South Station two hours late, at 2 p.m. on April 12, 1918, I discovered where the true Hub of the Universe could be found.

I had been gone 35 days. Banging out stories, riding overnight sleeper cars, playing cards, keeping tabs on the Babe. . . . As fun and exhausting as it was, I knew every day it lacked true emotional nourishment. Every minute of it I felt incomplete, like a puzzle without a piece, a clock without a chime and a bird without a song . . . until . . .

Delia stood there like an angel upon this earth. For a moment I was back at the hall at St. Augustine’s for the Leap Year’s Party, when I caught her beautiful face from across the room as if no one else were there. In an instant I fell in love all over again.

This was South Station, a monument of Neoclassical design that was just 19 years old. The scope of it was massive, with its tall doors, Ionic columns, oversize windows, large balustrades on the third floor and roof and more people coming in and out than any station in the entire world. But all of it fell away to nothing at the moment that Delia and I fell into each other’s arms.

There was nobody else. No other sound.

We held on tight. Forever in my heart I wanted to hold this feeling, this profound blend of love, appreciation, blessedness, comfort and happiness. But life can have cruel disregard for our wishes. In her clutch I could not fathom that life would never be as terrible as it would be in 1918, and the start of the annus horribilis loomed just two weeks away.

Kindest Regards,

Edward F. Martin

Click here to read Chapters VI - XIII of Letters From the Hub.