The Red Sox' run to the World's Series begins, and the grippe emerges.

Editor's note: Click here to learn more about the story behind Letters From the Hub. Click here to read the start of the series, and click here to read the end.

Dear Tom,

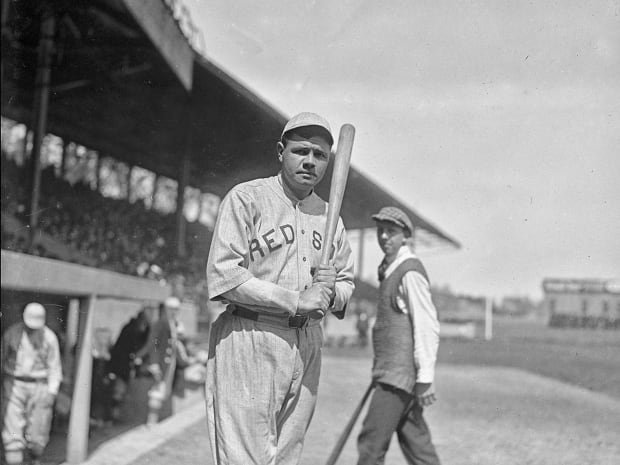

Babe Ruth went to Harvard.

That sounds like an impossibility, but remember, I began this story by telling you that absolutely everything I am telling you is true, and so it is with the Babe going to Harvard. Miserable cold seized Boston on April 13, the day after we returned from spring training. Snow covered the field at Fenway Park. The team arranged for a workout at the indoor facility at Harvard, where the coach at the time was Hugh Duffy, the former Boston outfielder.

Expectations for this team were sky high, especially from Frazee, who I noted the day of the Harvard excursion “spent something like $75,000 during the winter to assemble a bang-up outfit.”

The snow melted in time for the April 15 opener against Philadelphia at Fenway. Mayor Andrew James Peters threw out the first ball. The Royal Rooters band, the musical ensemble from the rabid Red Sox fan club, provided pregame entertainment. As I wrote, the band “dashed off numbers that either made restless feet misbehave or produced visions of shell-torn towns in France.”

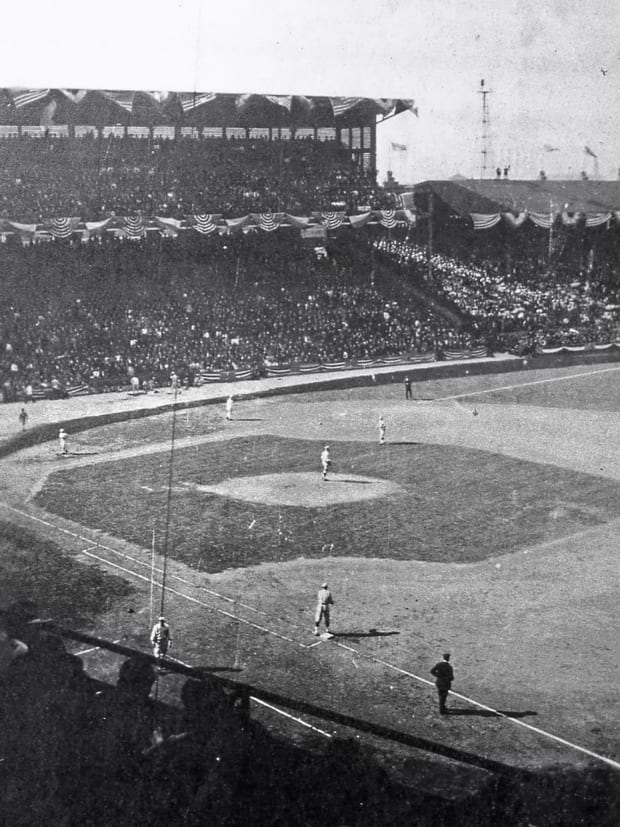

Behind Ruth, on the mound for his third straight Opening Day start, the Red Sox won, 7–1. Fenway Park was over 60 percent empty. The paid crowd was 7,184. This was what baseball looked like during war time.

It was an unusual crowd. You might call it a reflective bunch. They never failed to applaud a great play, but there was a sort of conservation of appreciation apparent.

Frankly, some people wondered whether baseball should be played at all while we were at war. In the summer of the previous year, 1917, American League president Ban Johnson offered to shut down the league for the duration of the war. President Wilson told him not to do it.

“People must be amused,” Frazee said. “They must have their recreation, despite the grim horrors of war.”

This is all you need to know about how important baseball was in the fabric of American life: U.S.soldiers were being outfitted with baseball equipment, not just guns. Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith organized a fundraising drive to provide baseball gear to every U.S. military training camp. The YMCA, Hillerich & Bradsby and Spalding were among the companies to answer the call.

The program was expanded to provide baseball equipment to the Doughboys overseas. As the Red Sox opened their season at Fenway, U.S. soldiers were playing baseball in Poitiers, France, with H&B bats and official red-and-blue stitched baseballs that included a red YMCA stamp and the words “American” and “France” above and below the triangle logo. Baseball, our sport, was considered essential to the morale of our fighting troops.

Right around Opening Day, Delia’s father took ill with pneumonia. Michael F. Mulkern was as hale and hearty a man as any of the firefightersI knew in South Boston. He had left Ireland when he was just nine years old and eventually made a good life for himself, his wife and three children while working for the Boston Water Department. He was a fiercely proud teamster. Against this dreaded pneumonia, even someone as tough as Michael met a formidable opponent.

He was on my mind each day, even at the ballpark.

On April 23, the Red Sox and Yankees were locked in a scoreless game at Fenway Park. In the bottom of the ninth, Barrow, who had not managed in 14 years, had played not a lick of pro ball and who sat in the dugout in the finest of suits, happened upon an idea nobody had thought of in the previous three years: use Babe Ruth as a pinch hitter.

Barrow first tried it in the third game of the season against Connie Mack and the Athletics. In that game Boston trailed by one with runners at second and third and no outs in the ninth inning. Barrow told Ruth to bat for catcher Sam Agnew, who was off to an 0-for-10 start. Mack promptly issued an intentional walk to Ruth. The next batter, Wally Schang, delivered a game-winning two-run single.

Against New York a week later, first baseman Dick Hoblitzell, who had one hit in 28 at bats in the season, was due to bat with a runner at first base and one out in the ninth. Pitchers Bullet Joe Bush of the Red Sox and Hank Thormahlen of the Yankees had given up nothing. Barrow again sent Ruth to pinch hit. With Amos Strunk on first base, Yankees manager Miller Huggins elected to let Thormahlen pitch to Ruth.

Ruth smashed a single to center. Strunk raced to third. Huggins elected not to pitch to Stuffy McInnis, hoping for a double play by loading the bases with an intentional walk. Instead, George Whiteman came through with a sacrifice fly for another Boston win. The winning rally was made possible by Barrow’s making use of Babe’s bat.

The Red Sox were 7–1. Word was beginning to get out that Ruth, thanks to Barrow’s ingenuity, might be much more than one of the league’s best pitchers. After the comeback win the happy team piled into a 7 p.m. train at South Station bound for Philadelphia, where the Red Sox were to play a four-game series against the Mackmen.

I did not go with them. The condition of Delia’s dad had worsened. He was taken to City Hospital. Walter Barnes, my editor, told me to take as much time as I needed. The Globe would cover the games in Philadelphia with re-writes of wire reports. “Special Dispatch to the Globe” replaced the usual “By Edward F. Martin” byline.

Two days later, on April 25, 1918, Michael F. Mulkern, the epitome of the American dream, died at City Hospital. He was 59 years old.

The obituary the next day noted the funeral mass would be held at Gate of Heaven Church in South Boston. At the top of Page 1 of that edition was a headline that seemed frightening in its thickness: GERMANS OCCUPY KEMMEL HILL. The details were gruesome. At 2:30 a.m. the Germans began attacking French troops with gas grenades, while 96 airplanes dropped700 bombs. Outnumbered three-to-one, the French stood no chance on that hill in Flanders, Belgium. Of the 5,294 French soldiers who were killed, only 57 were identified.

With Mr. Mulkern dead and the war birthing what had been unimaginable horrors, this was the kind of day that shakes your faith. Little did I know that the situation was far worse.

I look at Mr. Mulkern’s deadly case of pneumonia much differently now than I did then. Maybe it was a warning sign we all missed—just like those at U.S. military training camps around the same time. While we were fighting the world war in Europe, a killer lurked among us.

In July 1917, construction had begun on an enormous divisional cantonment training camp at the Fort Riley facility near Junction City, Kansas. Camp Funston was more of a city than a military camp. As many as 4,000 buildings went up around grid-style city blocks to accommodate 40,000 soldiers. As in a city, there were theatres, libraries, schools and a coffee roasting house. The soldiers slept in two-story barracks with 150 beds in each sleeping room—one for each member of an infantry division. Most of the men were draftees from Midwestern states being prepared to fight overseas. Officers from France and Britain were brought in to train them.

Conditions were harsh: frigid winters, prairie dust storms and particulates of black ash caused by the burning of manure from the thousands of swine, horses and mules.

On March 11, 1918, Private Albert Gitchell, a mess cook, woke up feeling ill. He was achy and feverish. His throat burned. This was no common cold. He reported to the infirmary. He was found to have a fever of more than 103 degrees. As a precaution, Gitchell was placed in a private tent reserved for potentially contagious conditions.

Gitchell had spent the previous evening doling out meals to fellow soldiers. It was no surprise then that within hours a stream of ill soldiers followed him to the infirmary: 107 by lunchtime, 522 by the end of the week, 1,127 by the end of the month. They shared similar symptoms: high fever, terrible coughs and blue faces. Forty-six wound up dead.

You must understand how little we knew about infectious diseases in 1918. It would not be until the 1930s that this was identified as an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Influenza was not a reportable disease. No government health agency tracked it. No pandemic plan existed.

We had no tools to fight it. There were no vaccines. Antibiotics had not yet been developed. No flu antiviral drugs had been developed. There were no critical care measures. No intensive care support. No mechanical ventilation.

To this day, it is virtually impossible to know for sure where it originated. Some people speculated that it came from Europe. Spain was hit with a mild strain in February. Did the French and British officers carry it back to Camp Funston?

Another theory suggested it began in the remote Canton region of China, and that it spread to Europe by Chinese men hired to dig trenches for the French army.

Yet another theory would emerge: The outbreak began right here in America, just 300 miles west from Camp Funston in Haskell County, Kansas, a farming community so remote it included just three people for every square mile. The 1,720 residents lived in sod houses and tended to cattle, swine, grain and poultry. The pieces of this theory do fit neatly.

Among the residents of Haskell County was Dr. Loring Vinton Miner, who lived in the town of Santa Fe. Miner was a large, crusty man who turned 58 that winter. He dabbled in politics and so loved ancient Greek culture that he reread classics in that language. In January 1918 Miner noticed that an odd number of Haskell residents were coming down with a strange illness. Miner saw 18 severe cases of the influenza in tiny Haskell County. Three people died.

The outbreak happened several weeks before Private Gitchell, the mess cook, reported to the Camp Funston infirmary. What happened in between?

The Santa Fe Monitor reported that one of Haskell’s residents, Dean Nilson, “surprised his friends by arriving home from Camp Funston on five days furlough,” after which he returned to camp. It also mentioned that Ernest Elliot, a resident whose son was among the afflicted, left during that in-between period to visit his brother at Camp Funston, and that John Bottom, another Haskell resident, left to report for duty at the same base.

We do not know for certain that the virus originated in Haskell and was carried to Camp Funston. But we do know the cramped quarters at Camp Funston provided perfect conditions for its spread, that infected soldiers carried it as they moved to camps around the U.S. and the world, and that Dr. Miner, the Greek-loving country doctor, sounded the first public alarm of a deadly influenza.

Though influenza was not classified as a reportable disease, Miner found this strain so dangerous he decided he needed to warn the public. On April 5 he published a warning about it in Public Health Reports, a weekly journal produced by the U.S. Public Health Service for the express purpose of putting health officials around the world on alert about a communicable disease. It was the first recorded alert that a virus was adapting to humans.

It received little attention. It remained the only reference to influenza in Public Health Reports through June of 1918.

Your Friend in Baseball,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Tom,

In May 1918 I was not worried about an influenza pandemic. I was worried about the Babe’s tonsils.

The Red Sox did not play home games on Sundays. It was against the law in Boston, as it would be until 1929. So sacredly held was the sabbath that you could not even play chess or checkers outside on a Sunday in Boston in 1918. Most people worked Monday through Saturday. Games at Fenway typically started at 4 p.m. The working class had one clear day to see the Red Sox play and yet baseball on that day was illegal.

Sunday May 19, 1918 happened otherwise to be a perfect day for a ballgame. It was the warmest day yet of the spring. Babe and his wife, Helen, took advantage of the off day and the fine weather to join many of the common folk for a day at Revere Beach, a public resort area five miles north of Boston. It was known as The Coney Island of the East. It featured amusement rides, dance halls, theaters, carousels, roller coasters and five miles of a crescent shaped sandy shore that provided the best bathing beach for miles. The Babe had been bothered by a sore throat for the past week, but this day seemed idyllic. He munched on a picnic lunch, drank warm beer, swam in the cold water and horsed around with locals in a casual game of baseball.

At home that night, Babe’s sore throat turned into something much worse. He ran a fever of 104 degrees. He had the chills. His body ached. His throat hurt. He had all the symptoms of the flu. When he showed up the next day at Fenway Park it was obvious to Barrow and Dr. W. Oliver Barney, the team physician, that Ruth was in no condition to play. (Carl Mays pitched the Red Sox to another easy win that day, 11–1.) Dr. Barney treated Ruth the same way he did any Red Sox player with a sore throat: He washed it with a swab of silver nitrate solution.

The next day, May 21, Ruth was scheduled to be the starting pitcher. He still felt awful but told Barrow he wanted to pitch. Dr. Barney refused to allow it. Ruth offered to play leftfield instead. But Barney told Ruth he was suffering from more than just a sore throat. This was serious, he said. He told him to go home and spend the next four or five days in bed.

Barney accompanied Babe home. They stopped at a Back Bay drug store to fill a prescription. There Ruth felt something gather and break in his throat. Suddenly he collapsed in great pain. He was rushed to Massachusetts Eye and Ear infirmary. His condition was listed as serious, though by evening under the care of throat specialist Dr. George Tobey he was out of danger. He could not speak. His throat was encased in ice.

The attack of tonsillitis has weakened Ruth considerably and he will have to lay around a few days and regain lost strength.

Ruth missed 10 games due to tonsillitis. By the time he was stricken, the public had come to clamor to watch him swing the bat, not just pitch. After less than a month of Ruth taking regular turns at bat, baseball writers were calling him “the Colossus” and “the greatest slugger of all time.” If it was shrewd of Barrow to use Ruth as a pinch hitter in April, then it was positively genius to turn Babe into a true two-way player in May.

You can pinpoint the change in baseball history to May 6. The Red Sox were playing the finale of a three-game series against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. I was home, taking off the six-game trip to New York and Washington for a few of my rare off days since deploying for the Vapor Valley in March.

Dick Hoblitzell was suffering from an aching hand and a worse batting average. He was hitting .102 with no home runs, surely the result of a late start to his spring training. Hoblitzell was a pleasant college fellow out of the University of Pittsburgh. He was late to camp because he took and passed an exam for the U.S. Army Dental Corps, which is why the guys called him “Doc.” And he was early to leave the team: In June he and his .159 average would be called away to the Army Dental Corps and stationed in El Paso, Texas. (Hoblitzell never did practice licensed dentistry, though he did set up a dental chair in his home and would fill cavities of neighbors and family without the use of novocaine.)

Hoblitzell also was known as “Hobby” and, owing to his education and gentlemanly ways, also as Ruth’s roommate in previous seasons. Like the others assigned to keep an eye on Ruth, Hoblitzell collected many stories about the Babe. He just never told one of them in the presence of his daughter.

With Doc hurting in more ways than one that day, Barrow penciled in Babe at first base, batting sixth. Though the Red Sox lost, 10–3, Ruth smashed a two-run home run into the upper deck in right field at the Polo Grounds. He blasted another pitch clear over the grandstand roof, but umpires ruled it a foul ball.

The next day in Washington, back at first base, Ruth whacked another home run, tying a record with home runs in three straight games. Ruth went 11-for-20. When the team returned home, Barrow decided on a new everyday lineup. He played Ruth in left field (when he wasn’t pitching), moved McInnis from third base to first and installed rookie Fred Thomas as the third baseman.

The lineup clicked—until tonsillitis stopped the Babe. Ruth’s return came in the second game of a doubleheader against Washington. There were 11,000 fans at Fenway Park, more than double the average crowd at the Fens in 1918. In an otherwise forgettable 4–0 loss to Doc Ayers and the Senators, Ruth emerged from the dugout in the eighth inning, swinging that telephone pole of a bat of his. His hickory hammer was 36 inches long and weighed between 40 and 54 ounces.Walter E. “Stonewell” Jackson, the field-level public address announcer, lifted his megaphone to his mouth and announced Ruth’s long-awaited entry into the batter’s box.

There was prolonged applause and cheering as Babe marched to the plate. It only goes to show that the dear old public approved of the way Babe stood off old Kid Tonsillitis.

Ruth was becoming not just a baseball star but also a true American icon, like Will Rogers, Al Jolson and Mary Pickford. I resisted the analogy, but some of my colleagues saw Ruth’s power as symbolic of the American might on the frontlines of the war. Soldiers in trenches in Italy and France awaited news of the latest Ruthian clout.

My main responsibilities for the Globe were to provide detailed game stories and columns chock full of news and notes. In the style of the times, I rarely used quotes from players. When I did, usually it was to provide something in the way of humor. From Murnane I learned the powers of nicknames and a good yarn. Often, I let the player tell his yarn in his own voice. That way the reader felt like he or she was in on the camaraderie I was able to enjoy every day.

Readers wanted personalities and storytelling, a far cry from the flavorless gruel in the feed bags they are forced to consume today. Sometimes when I read the sports pages now, I think I have stumbled into the business section. Ballplayers and managers are reduced to numbers, statistics, data, assets and salaries. The game is covered as if it were international banking. Nobody ever considered banking a pastime or spectator sport. Had Babe Ruth existed today he would be reduced to his Wins Above Replacement and Launch Angle.

Thank goodness it was different for me. For the Sunday Globe of July 14, 1918, I wrote a long feature on the Babe after sitting down for an exclusive interview. The only “numbers” I used in the entire story regarded his vital statistics: Ruth “just turned 24 years old, weighs 198 pounds and is 6 feet 2 in his stocking feet.”

I wrote about his approach at the plate, his baseball background, his love of acting in high school, his wife, his hobbies (hunting, fishing, golf, vaudeville), his wellness tips (“Keep outdoors a lot, inhale that old ozone and you will keep the doctor away”) and whatever else makes the Babe the Babe. I decided to begin my story as Ruth approached a turn at bat: with the intent of blunt force trauma:

Just bust ’em. Take a good cut and bang that old apple on the nose.

This Oriole boy, who is the last word in picturesqueness and the occupant of the brightest spot in the baseball sun, is indeed a most interesting character and unquestionably one of the greatest attractions baseball has ever known.

His name is on every lip these days, and not alone because he had been a consistent producer. It is Babe himself and his methods that help him corner the calcium this season. His appearance at the bat is a signal for a great outburst of applause; the way he swings, even though his bat just tears through the ozone at times, is itself a picture, but when he meets the ball – blooie!

Pitchers had quickly come to fear Ruth. I loved this quote from the Babe in my story:

“A base on balls is an obstacle in the path of progress. It is part of the game all right, but when you are up there crazy to give the old ball a ride and that fellow on the mound passes you it makes you feel as if you could wring his neck. I would rather get a punch in the nose than a base on balls.”

I knew Ruth was changing the game. I knew he was a box office hit. I knew he was great copy for us newspaper men. But I also knew that Ruth played an even larger role in America in 1918. War pressed upon your conscience with an almost unbearable weight most waking moments. To read the front page of the Globe on a daily basis was to read the exploits of the Grim Reaper. The Germans had U-Boats, nerve gas, Fokkers with twin machine guns and Gothas loaded with bombs.

Against what Frazee called “the grim horrors of war” we needed, as he put it, our amusement and recreation. Baseball, with its episodic drumbeat of games, was there for us almost every day. It could never completely counterbalance the frightful news from Europe. But it gave our minds mini vacations from the horrors. It made us smile. And no one in 1918 gave us a happier diversion from war than George Herman Ruth. I made sure to end my feature on that note:

One might go on indefinitely with a recital of the doing of “Babe” Ruth, but what is the use? Everybody knows him, and in these depressive days he is doing more than his share to provide the recreation and relaxation that so many need.

More power to him, and may his big bat continue to bust ’em.

Beneath the surface of the Babe’s rise to stardom, however, trouble was brewing. Ruth was chafing under the controlling ways of Barrow, the gruff manager. Barrow bristled at the way Ruth disregarded player curfews. He nagged him about it. He forced Ruth to write notes to him detailing what time he returned to his hotel when the team was on the road. Ruth, the son of a Baltimore saloonkeeper, didn’t respond well to boundaries, or anything else that stood between him and fun.

Ruth also knew the team had signed him to a $10,000 contract based on his pitching prowess, and as a two-way player he had become the most valuable asset in baseball. Ruth had found the double duty wearying, and lately had been telling Barrow his left wrist was too sore to pitch—but not to hit home runs.

The tension between Ruth and Barrow finally boiled over during a series in Washington. On June 30 Ruth hit his 11th home run, already just five short of the American League record. The next day was an off day. Barrow gave him permission to visit his home in Baltimore. He expected Ruth back in Washington early the following morning, July 2. Instead, Ruth did not report back to the team until just before the game that day against the Senators, putting Barrow in a foul mood. Barrow decided not to confront Ruth and, though quietly seething, put him in the lineup in centerfield.

Late in the game, with the Red Sox losing 3–0, Ruth struck out for the second time in three hitless at-bats. He made a show of his anger in the dugout. Suddenly Barrow snapped.

“That’s what you get for chasing a bad pitch on the first pitch,” the manager said. “That was a bum play, Ruth.”

“Don’t call me a bum. Not unless you want to get a punch in the nose.”

“That will cost you $500!”

“The hell it will! I’m through with you and this team!”

Ruth, as he put it, “made a few more remarks,” and finally left the dugout. True to his word, he kept going and did not stop until he was home again in Baltimore.

Jack Stansbury replaced him in centerfield. The Red Sox announced that Ruth left the game because of “stomach problems,” which, knowing Babe’s appetite and history, was not only plausible but familiar. The club said it expected him back in the lineup the next day for the game in Philadelphia.

Except the next day came and there was no Ruth in the lineup. There was no Ruth, period. He was fed up with Barrow and the Red Sox. He announced he was quitting the team and taking a job with Bethlehem Steel, where he would play for the Chester shipyard team in the Delaware River Shipbuilding League. Frazee called him and threatened to sue for breach of contract.

Back in Baltimore, Ruth cavorted with old friends at the bar at the father’s saloon at the corner of Eutaw and Lombard while the Red Sox were shut out, 6–0, by the Athletics. Sadly, this would be last time Babe saw his father alive. One month later, on August 24, George Herman Ruth Sr. would engage in a fatal fistfight with his brother-in-law, Benjamin H. Sipes, 30, outside the saloon. The elder Ruth flattened Sipes. Sipes got up and fought back. He connected with a punch. The Babe’s dad lost his footing on the curb and tumbled. He hit his head on the sidewalk. He was taken to University Hospital, where he died. He was 46 years old.

George Herman Ruth Jr., who looked just like his dad, said he had no intention of paying what was a massive fine levied by Barrow. The $500 represented five percent of his salary, the equivalent today of fining a $20 million player $1 million. He told people he didn’t know what was going to happen, but he did know he was tired of how Barrow treated him.

“I do not want to be fighting and being fought with all the time,” Ruth said.

Barrow sent a telegram. It went unanswered. That night in Philadelphia Barrow sent infielder Heinie Wagner on a mission: “Go to Baltimore and bring back Ruth.”

A shortstop on past Red Sox championship teams, Wagner was 37 years and a player-coach, with the coaching side of that title consuming most of his duties. A respected, quiet leader with a keen sense of humor, Wagner had replaced Johnny “The Crab” Evers on Opening Day in that mentor role. Ruth considered him a friend. Wagner was the perfect ambassador for the job. It worked. By 2 a.m., Ruth was in Philadelphia.

Barrow refused to talk to Ruth. He also refused to put him in the lineup for the morning game of the Fourth of July doubleheader. Between games Ruth took off his uniform and said he was done for good this time. Wagner and Harry Hooper talked him out of it. Finally, Barrow signaled he wanted the feud to end: He put Babe in the lineup for the second game. After the game they reached a truce: Barrow would rescind the fine and Ruth, who had not pitched for a month, would return to the mound.

Two days later, the fans at Fenway got their first look at Ruth since the tempest, though they would have to wait a bit. Barrow kept him out of the starting lineup against Cleveland, which briefly had slipped into first place while the Sox stumbled amid the controversy. Shrewdly, however, Barrow waited to deploy his weapon in a key spot mid-game.

Our own Mr. G. Babe Ruth, the widely known, buxom and blushing matinee idol, recently featured in Peck’s Bad Boy and The Prodigal Son, crashed into the calcium again against Cleveland yesterday.

A most desirable setting was provided for the temperamental star. The Sox were two behind in the sixth inning, had two on and none out when he came up to pinch hit for Walter Barbare. A mighty smash to the rightfield corner for three sacks was his contribution, this fine bust knotting the count and Babe scoring himself, what proved to be the winning run, as Wamby, who took the throw from Roth, chucked wild to third trying to nail Babe.

Everything appears to be absolutely OK between Messrs. Ruth and Barrow now. This is as it should be, if the club wants to win the pennant. The Sox can’t win without Babe nor can they win without discipline.

The Red Sox never let go of first place again. At the time, however, all of us knew baseball could be shut down at any moment.

With Colossal Regard,

Edward F. Martin

Dearest Tom,

Ever since President Wilson gave baseball the green light to continue in war time, the conflict only grew worse and the need for more and more manpower grew more urgent, both in Europe and at home. The first U.S troops left for France on May 28, 1917. By July 2, 1918, one million American men were fighting overseas. As the war deepened, so did the concerns about whether the National Pastime should go on. I took note of that debate in describing the crowd at Fenway in that July 6 game in which Ruth pinch hit his two-run triple.

The rain ceased about 1:30 and 15 minutes later Old Sol appeared. In spite of the bad weather 5,250 persons attended the game. The fact that more than 5,000 came out yesterday was ample proof that the public wants professional baseball.

Not everybody was convinced. In the summer of 1918, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker announced a policy known as “work or fight,” in which able-bodied eligible men were required to join the military service or find work in businesses considered “essential” to the war cause. Entertainers, including baseball players, were considered exempt.

On July 19, however, Baker changed course and ruled that baseball was a “nonessential” business. Dutch Leonard, a star pitcher for the Red Sox, immediately took a job with Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Mass. Baseball asked for an extension of the exemption through October 15 so it could complete the full season. On July 26, Baker ruled that baseball could play through Labor Day, which fell on September 2. After that, baseball players would have to join the military or go to work at an essential business for the duration of the war. The 154-game season would be cut to between 122 and 128 games.

For the next four weeks it appeared that there would be no World’s Series in 1918. Just 11 days before the end of the abbreviated season, the secretary of war made one exception to his “work or fight” edict: the World’s Series could go on because of the “intense interest of the soldiers in France.” He added that arrangements should be made for the World’s Series scores and descriptions to be transmitted overseas as soon as possible.

With one week left in the season, the World’s Series looked to be a matchup between the Red Sox and Cubs, two franchises that had combined to win almost half of the 14 World’s Series played to that point. On August 27, while Ruth was in Baltimore to attend to the funeral of his father, the Red Sox stumbled at home against Detroit, losing 2–1. The call to military service had so depleted rosters by then that the Tigers brought only 15 players to Boston.

We were 17 months into wartime. Doom and death continued to press hard on the American psyche. On that same day, the Fuel Administrationbanned the use of automobiles, motor-cycles and boats on Sundays east of the Mississippi River in the interest of conserving gasoline. Candy manufacturers discussed a further reduction of sugar in their treats. In the early hours of that morning an American steamer in the Atlantic spotted a submarine 15 miles away and instantly opened fire, sinking it. Only then did the crew realize their tragic mistake: the submarine actually was an American patrol vessel. Most of the sub’s crew died.

Something else happened that morning that went unreported in the newspapers but would mark the start of something even more catastrophic than the Great War, worse than anything seen by humankind before or since.

Just before the Red Sox were to play the Tigers, five miles down Storrow Drive from Fenway Park, two sailors reported to the sick bay at Commonwealth Pier. About 7,000 sailors were stationed there in packed, drafty quarters while coming and going from the European front. Those two sailors were the first known U.S. cases of what would quickly be a second, far deadlier wave of influenza.

The first wave had spread from Kansas to all the armies in Europe. It came to be known as Spanish Flu, not because it originated there but because Spain, as a neutral party in the war, was more forthcoming about its prevalence. The combatants did not want to signal weakness to their opponents or to rattle the nerves of families back home by reporting the spread of the illness.

The first wave of influenza spread across the globe largely among military units. Hoblitzell, the slumping first baseman who lost his job to Ruth, came down with it at his Army Dental Corps post in El Paso, Texas. Soldiers referred to it as “the three-day fever.” So broad was its reach that military attacks had to be postponed or scaled back because of a shortage of healthy men. Great Britain reported 31,000 influenza cases in June. By July virtually no corner of the world was left untouched by the illness.

On August 14, The New York Times reported: SPANISH INFLUENZA HERE, SHIP MEN SAY. Beneath the headline ran a story explaining that 10 people had died and as many as 200 were stricken on a Norwegian steam ship on its way to Boston. Eventually 40 percent of the U.S. Navy and 36 percent of the Army would become ill.

War is hell. But to an H1N1 virus, war is heaven.

The logistics of war are perfect accomplices to a killer virus. Armies of men in close quarters, be they in cramped barracks, holds of ships, trains, transport and fighting vehicles, or trenches on the front lines . . . a lack of proper sanitary measures . . . vessels transporting men and the contagion across oceans to different continents.

By August 27, when those two sailors reported ill at Commonwealth Pier, something far more insidious had happened to the “three-day fever.” The virus had mutated. Two days later, Friday, August 29, 1918, 50 sailors from the First Naval District were taken to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Chelsea, Mass. The medical director there, Lt. J.J. Keegan, knew quickly these sailors were suffering from something much worse than the common flu. Some were turning blue and were dotted with purple blisters. The mere act of breathing was a massive chore for them.

Dr. Keegan immediately ordered laboratory officers to take blood and throat cultures and blood counts of the afflicted. Within 36 hours, at least two of those laboratory officers fell sick to the same menace, the sign that this virus was highly communicable.

The sailors told Keegan the same story over and over about how they were overcome. One minute they were perfectly healthy, robust young men with no symptoms, not even a sore throat, and within an hour or two they literally were knocked to the ground in pain. Fevers shot up to 105 degrees. Muscle weakness, severe headaches and pain in the body and joints, especially the back, led most of the sailors to describe their state in the same manner: They felt like someone had beat them all about the head and body with a heavy club.

None of us in the general public knew yet about the epidemic at Commonwealth Pier, which made an enormous Labor Day parade a time-release tragedy of epic proportions.

September 2 was a beautiful day in Boston: sunny and 72 degrees. More than 150,000 people packed Revere Beach to mark the unofficial end of summer. At 10:25 a.m., the first marchers left the corner of Arlington and Beacon to kick off a Labor Day parade rechristened as the “Win the War for Freedom” parade. Men in their straw hats, women with their parasols and children waving flags filled the sidewalks as the parade moved from Beacon to Charles to Boylston to Washington to School before it returned to the starting point at Arlington and Beacon.

There were bands and floats, including an operational blacksmith shop in the back bed of a truck and a giant horizontal tubular boiler pulled by six horses, as tradesmen proudly showed their contribution to the war. One automobile carried a large portrait of President Wilson. It drew loud cheers on every block. The showstopper was a 50-foot model of a battleship, replete with guns that shot off great plumes of confetti.

Four thousand people marched in the parade. It was a spectacular display of patriotism.

And a spectacular transmission of a killer virus.

Nearly half the marchers were people in military service. One thousand sailors from Commonwealth Pier, where Dr. Keegan had an epidemic on his hands, marched shoulder to shoulder in rows of four for as far as the eye could see.

I was blissfully unaware of the contagion literally being paraded through the streets. I was in New York with the Red Sox for a doubleheader, after which we caught a 5:04 p.m. train bound for the World’s Series in Chicago.

Our train out of New York was scheduled to arrive in Chicago at 4 p.m. Tuesday. Game 1 was scheduled for Thursday at Comiskey Park, not Weeghman Park, because of its larger capacity. Chicago would host the first three games.

The Cubs had dominated the National League. They finished 10 ½ games in front of the second place Giants. They scored the most runs and allowed the fewest. Chicago’s two best pitchers, Hippo Vaughn and Lefty Tyler, were left-handed, and Cubs manager Fred Mitchell was willing to start them every game rather than let a right-handed pitcher deal with Ruth. I knew the Babe was the marquee attraction of the series. Before I boarded the train, I filed my story for the next morning edition.

There will be something lacking in any game that is played with the Oriole boy off stage. When Babe is not pitching, he will certainly be in that left sector. He is a natural ballplayer; the team plays with an up-to-the minute spirit when he is working, and in the games that he has been used in left field for the Sox he has manifested that he is there.

Babe has no fear of portside pitching. He has punished forkhand service, and facing “Hippo” Vaughn and George Tyler will not jar him one iota. Ruth is the magnet that will draw thousands of fans to the Series, and they will want to see him as a principal in every performance and not as a “prop” on the coaching lines. It is believed that they will have their wish.

Train rides, especially 23-hour train rides, with their clackety-clack lullaby and the swaying to and fro, tend to stimulate deep thinking. This Labor Day overnight trip was particularly inspirational, with no shortage of material about which to wonder and worry. As I lay in my sleeper bed, I thought about how the next week would be our Last Diversion, at least as far as the happy antidote of baseball was concerned. Over the past seven months I had swept the horrors of war under the rug of my conscious mind. It was an easy exercise to accomplish because of my love of baseball and the sheer volume of work required.

This labor of love was about to end, and only God knew for how long. Not once, however, even in the worst of my ruminations, either wakeful or in dreams, did I imagine what was about to happen over the next few weeks. The best and worst about our world converged in September 1918, as cataclysmic a month as could ever be imagined. The World’s Series, a world war and the worst plague to strike mankind all coalesced. And yes, Boston, my beloved Boston, would be the hub of this maddening universe.

Respectfully Yours,

Edward F. Martin

My Dear Thomas,

On the same day the 1918 World’s Series opened in Chicago, September 5, the Massachusetts State Department of Health issued a rare warning. Most people in Boston did not notice it. The influenza outbreak among the sailors at Commonwealth Pier was in its ninth day. More than 325 had been infected.

Dr. John S. Hitchcock, the head of the department’s division of communicable diseases, warned the virus would not remain contained within the sailor population. It was coming for Boston.

“Unless precautions are taken the disease in all probability will spread to the civilian population of the city,” Hitchcock said.

But Hitchcock, in a manner typical of public health and government officials, downplayed the danger.

“The malady appears to be in the nature of the old-fashioned grippe,” he said. “No deaths have occurred. The Naval medical authorities who have the matter in charge are doing everything humanly possible to control the outbreak. Now the daily list of cases appears to be diminishing.

“People should be reminded that under these conditions persons with coughs and colds are not choice companions, and that a good doctor is a friend. It should also be remembered that our past experience with this disease has shown the danger of persons suffering from it continuing at work or trying to return to their occupation sooner than safety dictates.”

The story (FEAR INFLUENZA OUTBREAK AMONG SAILORS MAY SPREAD) was buried on the bottom of page 6 of the Globe. Game 1 of the World’s Series ran on page 1. In fact, the first civilian case reported in a Boston hospital had occurred two days earlier, the day after the “Win the War for Freedom” parade.

Meanwhile, something unprecedented happened in the middle of the seventh inning of Game 1. In a nod to the boys fighting in Europe, a band broke out in its rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner. All of the Red Sox on the field at that moment, including Babe Ruth, the pitcher, removed their caps—except one. Third baseman Fred Thomas, a member of the naval reserve at Great Lakes, stood facing the flag in perfect military salute form. As the great Ring Lardner wryly pointed out in his “In the Wake of the News” column in the Chicago Tribune, Thomas struck the same still pose twice more that day when umpire Hank O’Day rang him up on strikes.

Beginning with World War II, amid another wave of patriotism, The Star-Spangled Banner would become a staple at every American sporting event.

The game had a patriotic flair. As military airplanes swooped, dove and dipped wings above, sometimes as many as a half-dozen at a time, Ruth won a duel against Hippo Vaughn, 1–0. Ruth stretched his World’s Series scoreless innings streak to 22. The game drew 19,274 fans, down from 32,000 in the same ballpark for Game 1 of the previous year’s World’s Series between the White Sox and Giants. Still, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey argued the crowd was substantial, given that most men aged 21 to 31 were involved in the war effort and that high railroad rates discouraged out-of-towners from attending.

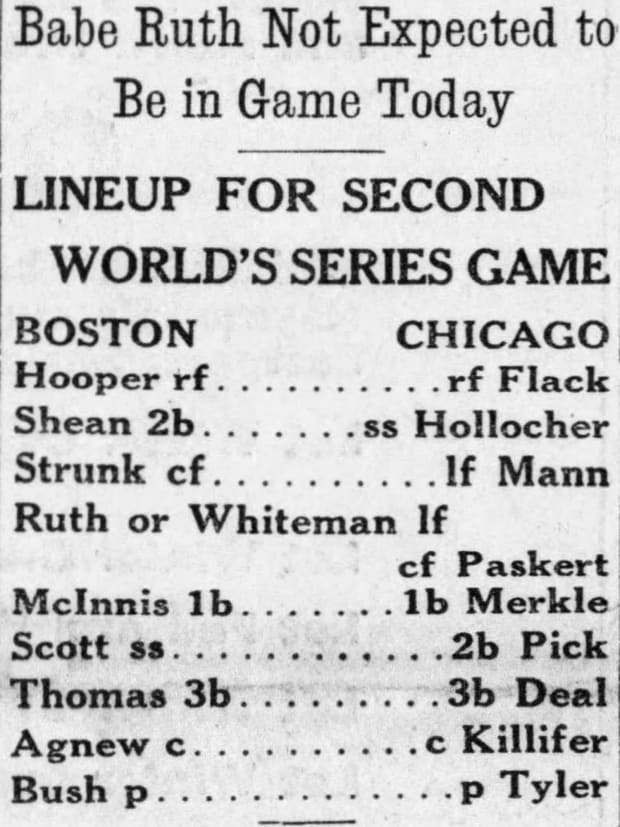

When Ruth stepped in to bat for the first time, in the third inning, Cubs right fielder Max Flack respectfully backed up 40 paces. Ruth lined out to center field. More significantly, Vaughn struck out Ruth in each of their next two confrontations. Both managers took notice. Fred Mitchell would start lefthanders Vaughn and Lefty Tyler in every game in the series to neutralize Ruth. It worked for the most part. Barrow would bench Ruth against them in games when he was not the starting pitcher.

I had misread Barrow. I wrote before the series that Vaughn and Tyler would not bother Ruth “one iota.” After Tyler pitched the Cubs to a 3–1 in Game 2, Vaughn pitched his second complete game in three days, only to suffer another hard-luck defeat, 2–1. Ruth did not play in either game.

It was a rather punk afternoon for G. Babe Ruth. Orders to intern him in the dugout are always given now when a southpaw goes to the hill. Babe is apt to go stale.

We boarded a special train that left Chicago at 8 p.m. and would arrive in Boston the next night at 10:50. Both teams and their press corps were aboard. The trip was notable for two reasons: the amount of complaining going on and an injury on the train to Ruth.

Players from both teams grumbled about the proposed cut of World’s Series receipts that had been decided by the National Commission, baseball’s governing body in those days. (Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis was hired two years later in the wake of the 1919 Black Sox scandal.) The winners would get $900 per man and the losers $300. Gate receipts were down because of lower attendance and reduced prices. Tickets for the World’s Series games at Fenway Park were slashed in half. Box seats could be had for $3.30. A seat in the bleachers cost 55 cents. The Commission also intended to donate some of the gate receipts to the war effort.

As for Ruth, the big lug was a carrier of calamity. I do not know how to explain it exactly, but stuff happened around the Babe. Tonsillitis. Stomach aches. The death of his father in a fist fight outside a saloon. Multiple fancy automobiles driven into ditches or fences. Trouble adhering to curfew. The misadventures of George Herman Ruth continued.

The train neared Boston on Sunday evening, September 8, when Ruth engaged in his typical roughhousing with W.W. Kinney, one of the batting practice pitchers. Suddenly Ruth smashed against a window and let out a yelp, and everything turned quiet. Ruth, scheduled to be the starting pitcher the next day, injured one of the fingers on his pitching hand.

I did not see the accident. I had to rely on the official word of the team to explain to my readers what happened. Its account was not in the same ballpark as the truth.

As the train in which the Sox were riding was nearing the city, the car in which Ruth was riding rocked and backed him through a window. An examination by Dr. Lawler showed that Babe was o.k. however.

Ruth and the rest of us made it to South Station a little after 11 p.m. without further incident. The Cubs headed for the majestic Brunswick Hotel in Copley Square. The Red Sox scattered to their homes to catch some sleep looking like a collection of ragamuffins. Before the train had even pulled out of Chicago, one of the players got the bright idea to punch a hole clear through a teammate’s straw hat, the favored headwear of the times. It wasn’t long before every straw hat on the train had a hole punched through it. Once we got to Boston, the players replaced their holey straw hats with caps—all except Ruth, the only one without headwear as we stepped onto the platform.

“Babe needs a cap,” I heard pitcher Joe Bush shout. “Send out to the dining car for a dishpan!”

“I don’t know,” Heinie Wagner said. “For that head I think a barrel would be a better fit!”

It was nearly midnight by the time I made it home to 1748 Columbia Road in South Boston. Delia waited up for me. Seeing her was like falling in love all over again. I had not seen her for eight days. It seemed like 800. We hugged, and I never wanted to let go, especially in these ominous times.

South Boston had become a strange place to me. There were almost no automobiles on the street, given the gas rations and limits on pleasure driving. There were few able-bodied young men around. Women pushed strollers, hoping the child in the pram would see his or her father again someday. I was not prime draft material because of my age, my terrible eyesight and my status as a married man and provider for my wife, my widowed mother and my widowed grandmother.

I awoke to gloom on the morning of September 9, the day of Game 4. An overnight soaker appeared not to have left entirely. Clouds threatened more rain. Fenway’s gates opened at 9:30 a.m.—five hours before Ruth and his mysteriously injured finger on his pitching hand would match up against Tyler of the Cubs in Game 4. Fans started arriving around noon, just as the clouds began to depart. By 1:30, as the teams began their pregame practice, the sky turned clear.

A band entertained the crowd. Prominent theatre people canvassed the crowd to collect donations for the Clark Griffith Bat and Ball Fund, the charity that sent baseball equipment to our fighting men overseas. More than 50 soldiers who had been wounded in France and were being treated at a local hospital sat in the grandstand as guests of the Globe. But only 22,183 people showed.

At precisely 2:30 p.m., Ruth delivered the first pitch of the game.

At the same time, just two miles away in the Corey Hill neighborhood of Brookline, a wild buzz of activity could be seen and heard at the corner of Summit Avenue and Lancaster Terrace, in the shadow of Brooks Hospital. The facility boasted one of the best views anywhere in Boston. Corey Hill was also known as “The Great Hill.” It sat 260 feet above sea level.

This was not a day to enjoy the view of the harbor and the city. William A. Brooks was the surgeon general of the Massachusetts State Guard as well as the medical director of the recruiting service of the Shipping Board. Brooks knew the influenza outbreak was overwhelming Chelsea Naval Hospital. He also knew his hospital did not have nearly enough beds to treat the overflow. He used his authority to order the Brookline company of the Massachusetts State Guard to erect medical tents between his hospital and Corey Hill Park.

While the Red Sox were playing the Cubs two miles away, what happened that day was an engineering marvel. Seven hours after work began, tents were erected, sewage lines were connected, lights and water systems were operational. Thirty-eight of the most serious patients were admitted.

With no serum or vaccine, Brooks spelled out a new course of treatment:

1. Strict protocols to guard against droplet infection of others from afflicted patients.

2. The greatest possible amount of nourishment and fresh air.

If you happened to walk past Corey Hill Park during the World’s Series (not that it was advisable), you would have seen a strange tableau that resembled a cross between Civil War triage and summer camp: seriously ill patients wrapped in blankets up to their neck, laying on benches under the sun in front of canvas tents. So important did Brooks consider fresh ventilation that patients even were kept outside during four days of rain.

Nurses and orderlies wore improvised masks: five layers of gauze fitted over a wire frame gravy strainer. They changed them every two hours. They wore gloves, gowns and head gear and washed their hands with disinfectant.

Brooks’s protocols did limit the disease’s spread. In one month, the open-air hospital admitted 351 patients. Thirty-five of them died, a much lower mortality rate than at the indoor hospitals. Of the 150 doctors, nurses and orderlies, only eight developed influenza.

Because of Corey Hill’s physical prominence over the landscape, those canvas tents could be seen from a distance. They stood as a chilling visual clue that influenza no longer was the exclusive worry of soldiers and sailors. Now it was obvious that the killer was here among us.

For those of us at Fenway Park, a very different ailment was the source of pressing worries, namely whether Ruth and his injured finger would hold up against the Cubs. Dr. Lawler dressed the finger in an iodine solution before the game, leaving an orange tint to it. The Babe did smack a two-run triple off Tyler and over Flack’s head for a 2–0 lead. On the mound, however, he was not sharp. He constantly pitched in and out of trouble before finally yielding two tying runs in the eighth inning. The runs ended Ruth’s record run of 29 2/3 scoreless World’s Series innings.

The Red Sox struck back immediately for an unearned run in the bottom of the eighth. The Babe went out for the ninth inning to close the 3–2 game but wobbled like an automobile with one flat tire. After a single and a walk, I saw Barrow do something he dared not do all year: He removed Ruth from the mound in the middle of an inning. He sent Ruth to left field and summoned Bullet Joe Bush. Like most everything else Barrow did, it worked.

The Red Sox put on a defensive clinic to salt the game away. First baseman Stuffy McInnis fielded a bunt and nailed the lead runner at third base. Then shortstop Everett Scott fielded a grounder and threw to second baseman Dave Shean, who threw to McInnis to complete the game-ending double play.

The way that Stuffy McInnis, Scott and Shean prevented scoring was a picture that Mike Angelo would have been crazy to paint.

Ruth allowed 13 base runners, six of them on walks, with no strikeouts. I rushed to the Babe after the game and asked him about the finger.

All the world should know, the Babe said, that it was not the finger that was troubling him, but the stuff that was on it, and the stuff that was on it was putting too much stuff on the ball, causing him to deadhead six of the Cubs to first, besides the reason for a wild pitch and a careless shot to second.

After the game, players and staff from both teams were invited by theatre producer Morris Gest to enjoy a play called Experience at the Shubert-Majestic Theatre. Just like at Fenway Park, the Cubs sat on one side and the Red Sox sat on the other. I was happy to spend the night at home with Delia.

The Red Sox led the Cubs three games to one in the series, which meant Game 5 was a potential clinching game. The players knew a Red Sox win also would eliminate whatever leverage they had against the National Commission to get larger World’s Series shares. It was time to act.

With Warmest Regards,

Edward F. Martin

Click here to read the final chapters of Letters From the Hub.