A story from the Great Beyond comes to an end.

Editor's note: Click here to learn more about the story behind Letters From the Hub. Click here to read the first five chapters, and click here to read the next four.

Dear Tom,

Neither team worked out on the field before Game 5. At 2:30 p.m., with 24,694 people in the stands at Fenway Park for the scheduled first pitch, the field remained empty except for some mounted police sent there to maintain order. The players refused to play. They effectively had gone on strike over money while a world war was raging and a pandemic was about to explode.

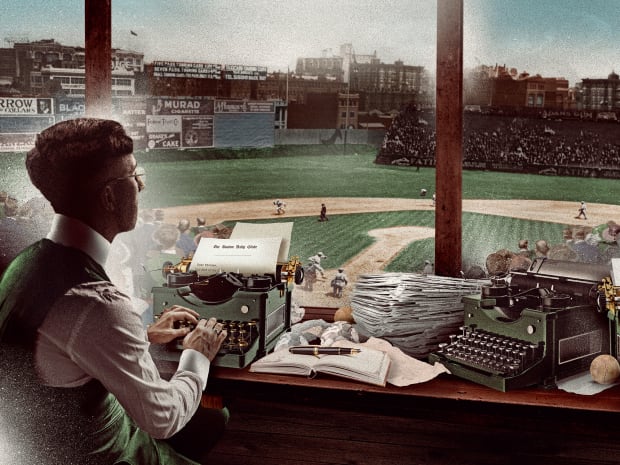

Arthur Duffey, a columnist for the Boston Post, pounded angrily at his keyboard in what was a typical reaction from my colleagues. It could have been written during any labor dispute in baseball’s history, including 2020 regarding pay in the age of the coronavirus.

“It’s a mighty good thing professional baseball is dead,” Duffey wrote. “The game has been dying for two years, killed by the greed of players and owners.”

Eventually, the players reluctantly gave in. At 3:15 p.m., John Fitzgerald, the public address announcer, raised his megaphone to his mouth and read to the crowd a brief letter from Red Sox outfielder Harry Hooper that explained the players’ position. The game, he announced, would begin in 15 minutes.

The Fenway folks had little to cheer after that. With Ruth back on the bench, Vaughn shut out the Red Sox, 3–0. It was his third complete game in six days, over which he allowed a total of three runs.

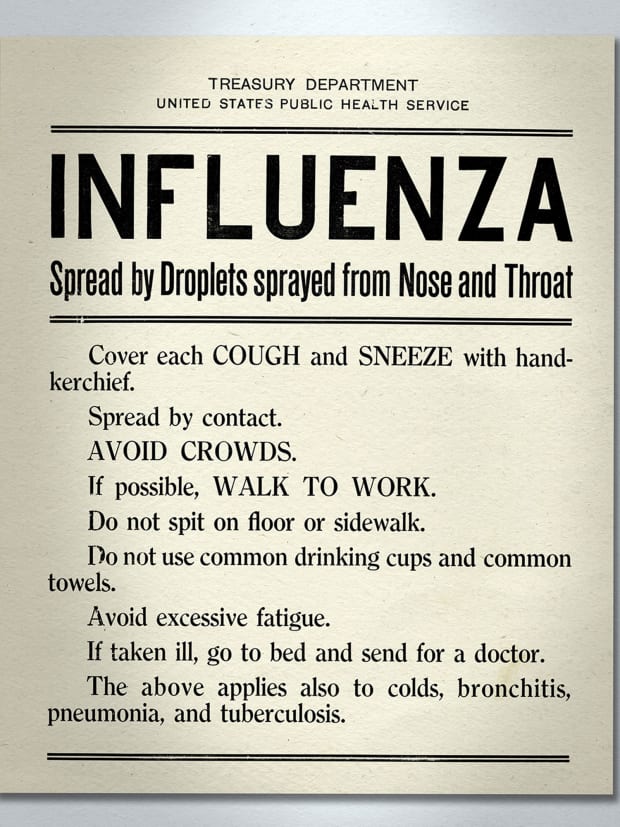

Game 6 the next day dawned with the literal and figurative clouds befitting a funeral. It was in every way a forbidding day, beginning with a note in the Globe about influenza:

Avoidance of crowded cars, elevators, or buildings is recommended. Common drinking cups or towels should be taboo. Care should be taken against spreading of the disease through sneezing or coughing by infected persons; the handkerchief should be used in these emergencies.

A Red Sox win would mean the end of baseball throughout the duration of the war, which looked as if it could be years with the way it was raging. Worse, the player strike before Game 5 left an awful taste in the mouths of fans who wanted to think of baseball as a pleasant diversion. Many people instead thought of baseball players as ungrateful louts for getting $900 for playing baseball while young men in the trenches of France were being paid $30 a month to contend with mustard gas and German bombers.

Only 15,238 turned out for Game 6. It was the smallest crowd of the series.

The game resembled the other five: a taut contest dominated by pitching and defense, especially by the Red Sox. Every half-inning, a carrier pigeon left Fenway Park with an update strapped to one of its legs. It flew the 40 miles northwest to Camp Devens, where thousands of the 40,000 soldiers were coming down with influenza. The pigeons did not have much to report.

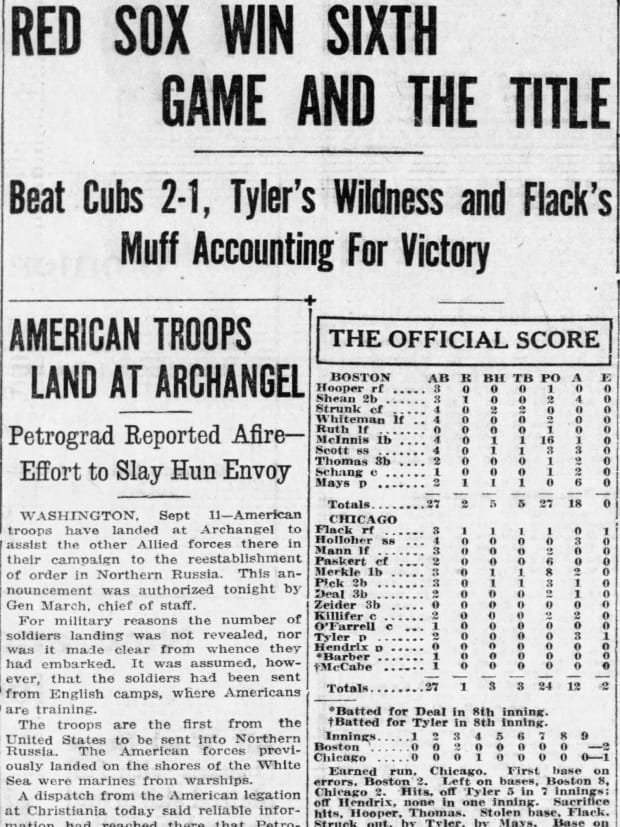

With Ruth again on the bench, the Red Sox scored two unearned runs in the third inning. The Cubs scratched out a run in the fourth against Carl Mays, who I called “the blonde Adonis with the submarine service” and who expected to be inducted into the Army any day.

But there was no more scoring. Mays retired the last 12 batters he faced in a season in which he pitched 311 1/3 innings. With two outs in the ninth, Les Mann of the Cubs hit a routine ground ball to second base. Dave Shean scooped it up and threw to Stuffy McInnis.

For the fourth time in seven years, the Red Sox were World’s Series champions. Their next triumph would take 86 years.

Boston is again the capital of the baseball world, history repeating itself yesterday when the Red Sox, who have never faltered in this great classic, defeated the Cubs, 2–1.

It was a ballgame that nobody who was present will forget. It left too many lasting impressions.

Something caught my eye as I finished writing for the morning edition of the Globe. As a cold, dull dusk fell over Fenway like the lowering of a heavy theatre curtain, I watched some of the veteran scribes slowly pack their typewriters and cases. Typically, the last game of a World’s Series feels like the last day of school. It is boisterous. There is some joy in knowing that the long journey is over, and equal excitement about some time off before the next one begins. This one was different. It dripped with melancholy. I could see it in the old men as they trudged slowly into a great unknown. I thought about Tim Murnane, my mentor, and what a life without baseball might have looked to him, especially at an advanced age, and I understood the slow shuffle in their steps.

I referred to this somber goodbye as “one of the pathetic sidelights” of the end of the season. These were men, I wrote, “to whom baseball has brought them many associations that they prize dearly.” Now it was over.

These veterans of the baseball press, who probably never thought they would see the day come when baseball would have to pause, realize that a great opportunity was lost to send the old pastime back into the wings in a blaze of glory.

Indeed, the next day was a somber one, with almost none of the euphoria you would expect in the afterglow of a World’s Series win. Frazee handed out checks to the players. They signed souvenir baseballs. They talked about where they would go next. Many were headed to shipyards or oil fields as part of the “work or fight” edict.

It was official: Baseball no longer was considered essential to the people of the United States. That same day, with such prevalent casualties and illness among the fighting forces, brought about another National Registration Day. All males between 18 and 45 were required to register for service, representing about 13 million men.

Kindest Regards,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Thomas,

Influenza cases around Boston were mushrooming. On September 13 the count of infected sailors from the First Naval District was 1,697. Eighteen doctors and nurses there were stricken. Camp Devens had more than 1,000 cases. The pandemic was jumping into the civilian population, especially as sailors and soldiers returned to their hometowns on furloughs.

Public officials sounded no alarms. In fact, they went out of their way to downplay the severity of the outbreak.

Dr. William Creighton Woodward picked an unfortunate year to be the Boston health commissioner. Woodward, who attended Georgetown Medical School, had been a key figure in his hometown of Washington D.C. in the fight against typhoid fever a decade earlier. He left Washington to take the Boston job in the summer of 1918. He was 51 years old. On September 13 he reassured the city it was “in no danger” from the epidemic. He said at the first sign of a cold people should isolate themselves, get into bed and take cold remedies.

Lt. Col. C.C. McCormack, the division surgeon at Camp Devens, said, “There is no cause for alarm. It is nothing more than the grippe, unpleasant, but in no way serious if due care is exercised.”

On that same day, Camp Devens, despite the contagion on its hands, held a military review parade. Thousands of soldiers marched shoulder to shoulder. A display of patriotism trumped public safety. Within 48 hours the number of cases at Camp Devens jumped from 2,000 to 3,000.

On the 17th, McCormack met the press again at noon. The cases at Camp Devens had soared to 3,500. McCormack said the epidemic was on the wane. He assured the public, “There is nothing to get fussed over.”

On the same day, Woodward, the health commissioner, gave advice to people on how to ward off influenza: “remain outdoors as much as possible on warm, dry, sunny days. A half-hour’s sun bath, he says, means sure death to the germs.”

Woodward and Dr. William H. Devine, the director of medical inspection, kept schools open. They argued that by being in school students were less likely to be infected, because teachers, principals and nurses were doing everything in their power to head off the epidemic.

Meanwhile, hospitals neared a breaking point. At Boston City Hospital, 38 nurses took sick. The hospital put out an urgent call for more. Physicians were overwhelmed; about 30 percent of the country’s doctors were serving in the military.

The next day, September 18, Woodward could no longer deny the obvious: The epidemic was raging in Boston. He estimated there were more than 3,000 cases in the city. Forty people had died in the past 24 hours.

“With the grippe making headway in every neighborhood, rich or poor, there was nothing to be gained by denying its presence,” he said.

Doctors had almost no weapons against it. The U.S. surgeon, the Navy and the Journal of the American Medical Association all recommended the use of aspirin, which beginning in 1899 was developed and marketed as a brand name by Bayer, a German company. (Conspiracy theorists in the U.S. government promoted the idea that the company introduced the virus into America by lacing aspirin tablets with it.) The medical professionals advised taking up to 30 grams a day. Later we came to learn that such a dose is more than seven times beyond a safe limit. Because one of the symptoms of aspirin poisoning is fluid in the lungs, many deaths may have been hastened by overloading the system with aspirin.

On September 20, Camp Devens announced the end to furloughs. For many, it was too late. At the time, more than 100 soldiers were stricken while at home and were unable to return, in addition to exposing friends and family to the virus. The case count at Camp Devens was up to 5,000.

On the same day, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then the assistant secretary of the Navy, quarantined at his mother’s home with the virus. He was stricken on his voyage home after visiting France and England.

Deaths mounted exponentially in Boston. In the week ending September 14—while the World’s Series was played—influenza killed 19 civilians in the city. The next week it killed 172. And the next, 610.

Meanwhile, Babe Ruth was getting out of Sudbury and making the transition to “essential” work. First, he made himself some money as a hired gun. Four days after the World’s Series ended, Ruth pitched against Dutch Leonard, his Red Sox teammate, in an independent game in Hartford for the benefit of local men serving in France. Reports said Ruth was paid $1,300 for the appearance, topping his share for winning the World’s Series. To help raise money, Ruth donated the baseball from his two-run triple in Game 4. He won the duel against Leonard, 1–0. The 5,000 or so fans who crammed the field got their money’s worth when Ruth slammed a long fly ball off a Bull Durham sign in center field. The locals said it was the first time anybody remembered a baseball hit to that extreme distance. The next weekend Ruth would be in Springfield, Mass., and Hartford again picking up some more cash in these town ballgames.

In between, from September 19–23, Ruth and his wife, Helen, stayed at the Hotel Weimer in Lebanon, Pa. He was there to talk with Charles “Pop” Kelchner about taking an essential job at the Lebanon plant of Bethlehem Steel. To be blunt, Kelchner was recruiting Ruth to sign on with the factory so that he could play on Lebanon’s baseball team in the Bethlehem Steel League. Pop ran the plant and managed the team. During the “work or fight” period it was not uncommon for baseball players and entertainers to be hired for publicity value and not for substantial work.

Kelchner first made a key move to entice Ruth: he signed Sam Agnew, who was not only Ruth’s Red Sox teammate. He also was Ruth’s personal catcher. Moreover, Helen and Agnew’s wife were close friends.

Agnew was 31 years old and a career .204 hitter. He stuck around baseball for seven years because he was a brilliant defensive catcher and was smart at running a game from behind the plate. Teammates called him “Slam,” which was a derivation of his name, though it also described what Agnew did to Senators manager Clark Griffith during a bench-clearing brawl in 1915. Agnew punched Griffith in the face. Boston pitcher Carl Mays said it sounded like a telephone snapping. Blood flew. Agnew was arrested on the field. A paddy wagon drove onto the field and hauled him off to jail. Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan bailed him out. Charges were later dropped.

On Sept. 25, Ruth decided he would join Agnew and take a job with the Lebanon plant for the duration of the war. That same day he bought a 1918 Scripps-Booth touring car (factory price: $1,195). He and Helen took an apartment at 718 Chestnut Street.

The same day Ruth was car-shopping and settling into Lebanon, Woodward knew the influenza outbreak in Boston required action. He closed the public schools. That same day the Emergency Health Committee recommended a ban on public gatherings. Woodward agreed. The following day all theatres, movie houses, soda shops, dance halls, saloons and all other public gathering places were ordered closed. He recommended churches close for at least 10 days. He urged people not to travel on trains, streetcars and subways.

Just two weeks ago I was covering the World’s Series and laughing with the Babe on overnight trains. Now my city was on lockdown. Streets without activity, schools without children and bars without mirth, the Hub of the Universe came to a frightened standstill.

St. Eulalia’s held no Sunday services, but I prayed from home that the epidemic would grow no worse.

It did. Worse than I ever imagined.

Delia started to run a fever.

Wishing You Well,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Thomas,

After I wrote my story the day after the World’s Series about the Red Sox’ dividing up their meager winning shares, I went on vacation. I did not actually go anywhere. A vacation to me was spending time at home in South Boston with Delia. I was away from my love for too long. I needed a break, and the Globe provided me two weeks of recuperation.

Six months of baseball writing had worn me down without my even knowing it. Writing two stories a day on deadline, enduring long train rides, keeping track of what Babe Ruth was up to on the field as well as off it, rushing to telegraph offices. For six months a baseball beat writer runs on adrenaline, coffee and the satisfaction of the occasional snappy, pitch-perfect piece of prose. Then when it ends, especially this year against the backdrop of war, you simply deflate and beg for the luxury of nothingness.

For a week I slept, hung around the house and followed the grim advances of influenza. Boston went on lockdown. So overwhelmed were the hospitals that an emergency “hospital train” was dispatched from Maryland to Boston. Its cars would be used to treat patients. At each stop along the way local health officials would meet the train and beg to use the doctors, nurses and equipment on board. But physicians aboard the hospital on rails said they were under strict orders to bring the train to Boston without delay.

In Boston, news about influenza had become as pervasive and as crushing as the news from the war. Everybody had their own ideas and remedies about how to fight this killer.

On September 25, for instance, an ad ran in the Fall River Daily Globe shouting, “What you think is Spanish influenza may be a mere cold or cough. Get rid of it by taking Dr. J.O. Lambert’s Syrup.”

I did notice the occasional updates on the Babe, the most famous and underworked employee at the Lebanon, Pa., plant of Bethlehem Steel. His weekends were spent on ballfields in front of big crowds. Influenza was not the same problem there as in Boston. On Sept. 27, Ruth went hitless against Red Sox teammate Bullet Joe Bush, who pitched against Lebanon for a team of assorted big leaguers. The next day Ruth pitched his team to a 6-5 win over Harlan Shipbuilding.

The following day Philadelphia staged a huge patriotic day parade. As many as 200,000 people turned out. As with the parade in Camp Devens, such a mass gathering, especially with soldiers from nearby cantonments, was a horrible idea. Two days later Philadelphia had a full-blown epidemic on its hands.

It was during that week that my worst fears were realized.

Delia began to run a high fever. Unable to leave her bed, her body ached all over. Alternately, she shivered with chills and felt warm. I did my best to keep her nourished and comfortable at our home on Columbia Road. She kept layers of blankets pulled up to her chin.

The signs were ominous. Her condition grew worse. Delia was 31 years old and had been perfectly healthy, the very kind of person most at risk from this insidious virus.

I attended to her every minute of every day.

Until I fell seriously ill with the same horrible, relentless symptoms.

It felt just as those sailors at Commonwealth Pier described to Dr. Keegan when this second, angrier strain of influenza began almost exactly a month ago: as if I had been beaten with a club up and down my body.

It was October 1 when I no longer had the strength to care for her. I confined myself to a bed in an adjoining room. Our world had turned so quickly. Gravely ill in our home in adjoining rooms, we prayed to God to give us the strength to live.

On that same day, Woodward, the city health commissioner, maintained his sunny outlook, which in this case had a literal application on a 61-degree day.

“The present weather is destructive to any influenza germs that may have been lurking,” Woodward said. “Sunshine is the greatest enemy of the germ, and fresh air goes far to eliminate it.

“Everything gives promise of the speedy recovery of the sick and convalescent and precludes the possibility of the influenza wave spreading. . . . Apparently the climax of the crisis has been reached . . .”

Woodward’s words were a cruel joke at 1748 Columbia Road in South Boston. Delia and I were fighting for our lives. The act of breathing, the simplest definition of life, typically requires neither effort nor conscious thought. Now we had to work so hard at it. It felt as if we were at the bottom of the ocean. The crushing pressure against our chests seemed to push all the way into our souls.

I wanted air. I wanted light, beautiful, fragrant air. I wanted the kind of air wafting easily through my lungs like the air on a moonlit summer night on Telegraph Hill, as Delia and I walked hand-in-hand through Thomas Park as the lights below in the harbor and the city winked their approval at the luckiest couple in the world.

Instead, I labored to breathe. I pulled an arm out from underneath my blanket and gasped in horror. My skin was turning a blueish-purple.

It was nearing midnight when someone—in the fog of influenza, I know not who, but it could have been Delia’s mother—came to my room with an urgent message: Delia did not have long to live.

I insisted I see her one last time. I summoned what little strength I had to swing my aching legs out of bed and stand upright. Every joint in my body ached as I shuffled to her bedside in the room next door. She looked so tired and worn. Delia, my sweet Delia, the raven-haired teenage beauty I saw across the dance floor in St. Augustine’s hall at the Leap Year dance 14 years ago, the woman who unfailingly waited with love and patience for me to return from the odd hours of covering police officers, firefighters and ball players. . . . My Delia was leaving me.

I held her hand and kissed her forehead. Her eyes closed, her breathing barely noticeable, she gave the slightest smile.

Then Delia drew her last, labored breath. She was gone.

It is difficult for me to describe how I felt at that moment, but I will try. I felt a detachment, an uncoupling, like a train car from its locomotive. Without Delia, what gave my life purpose and momentum was gone. A story, an experience, a good day, a bad day. . . . All are nothing unless you have someone with whom to share them. I never felt so alone. I was the bird without a song.

Just when I thought my heart could not possibly ache more, I thought about Delia’s mother. Mary Donahue was born in 1865 on the middle of the three Aran Islands, which bob off the west coast of Ireland in county Galway like the dots of an ellipses. At 15 she emigrated to Boston. At 20 she married Michael Mulkern of the Boston Water Department, who was 11 years old when he left those same Aran Islands for America.

Michael and Mary started a family two years later with the birth of a baby girl in 1887. They named their first-born child after Michael’s mother: Bridget Agnes Mulkern. Everybody called the baby Delia, a common nickname from “Bridget,” which is the English derivation of the Irish name “Brighid.” It means “exalted one.”

Michael and Mary had four children. This would be the third child Mary would have to bury. A son, Michael, died at age three from scarlet fever. A daughter, Mary Josephine, died at age four from meningitis. Now, within just six months, Mary lost her husband to pneumonia and her first-born child to influenza. Only a son, Joseph, a machinist in Boston, remained.

Delia was one of 202 people killed in Boston by influenza or pneumonia on October 1, the city’s highest one-day toll of the epidemic. Her funeral was set for Friday.

I awoke the next day, Wednesday, October 2, in a state I did not think was possible: feeling worse. By the afternoon I was in such bad shape that my mother, Mary, insisted I be taken to a hospital. I was admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital, “where he is reported as comfortable,” according to the Boston Post. I would argue the use of the word comfortable was horribly misleading, but I will say at least I responded slightly favorably to initial treatment.

I was one of 242 infected persons admitted that day alone to Boston hospitals, bringing the total count of beds filled by pneumonia and influenza patients in the city to 1,320. The ban on public gatherings was extended that day to October 12. The closing of schools was extended to October 14. Some schools were turned into temporary hospitals. Teachers became lay nurses. Influenza had spread to 43 states.

Influenza chartered its own course with an insidiousness that man could neither control nor predict. Over the previous 20 days the daily death toll went up 13 times and down seven times. It killed some people within a day, others in a week or so. The one commonality seemed to be that if your bronchial symptoms continued beyond a third day, the condition most often was fatal.

The catch-all word people used for pneumonia and influenza was grippe, which derived from the French word for seize. That is what influenza did to you: It seized you. In its grip you were almost powerless. On October 3 it tightened its grip on me.

My condition worsened as the day went on. Every breath was a battle. This, I thought, is what it means to fight for your life. Never do you know how precious a breath can be as when you are on the borderline of life and death, the ultimate in binary outcomes. The hospital classified my condition as “dangerous.”

My lungs felt leaden. Air could hardly pass in and out of them. I was scared. Then, as I grew too weak to fight, I understood this killer was in full control of whether I would live or die. There was nothing I could do.

I closed my eyes. My last thought was of Delia. In my mind’s eye I saw her in all of her eternally youthful beauty. I knew that we would be together again.

At 4:53 p.m. I took my last breath.

Delia and I died only about 30 hours apart.

Most Sincerely,

Edward F. Martin

Dear Tom,

Twenty-three months after Delia and I were married at St. Eulalia’s Church, at the corner of O Street and East Broadway in the City Point section of South Boston, we were eulogized there.

The funeral for Delia had been set for Friday, but when I died on Thursday a double funeral was arranged for Saturday. The funeral began at our house on Columbia Road at 10:15 a.m., after which our bodies were brought to St. Eulalia’s for an 11 a.m. requiem high mass.

The church was packed. It seemed as if half the Boston police and fire departments were there. Retired firefighters who had worked with my father. Colleagues from the Boston press. Buddies from the Knights of Columbia and the South Boston High School Alumni Club. Representatives from the Red Sox and Braves. Delia’s friends and colleagues at Filene’s. So many beautiful floral arrangements you lost count.

Rev. C.M. Herdia of St. Mary’s Church in the North End celebrated the mass. Fred Walsh played beautifully on the organ, and Mrs. Percival Lewis of Allston and Anthony Marthone provided exquisite vocals.

My pallbearers were Edward J. Collins and Walter J. Ryan from the Globe, Richard J. Dwyer and Frank A. Lavelle from the Knights of Columbus; and friends Joseph McCarthy and Edward L. Landers.

The funeral cortege carried us a dozen miles or so to Holyhood Cemetery in the Chestnut Hill section of Brookline. Five members of the Kennedy family eventually would join us in being interred at Holyhood, including John F. Kennedy’s mother and younger sister. Just one week earlier, William Francis Murray, the Postmaster of Boston as appointed by President Wilson, as well as a former U.S. Congressman, had traveled the same route as I and so many others did in September and October. On September 21 Murray, a Harvard Law School grad and officer in the Spanish American War, also had died of influenza at Massachusetts General Hospital and was interred at Holyhood. He was 37 years old.

The Globe assisted my mother with the funeral arrangements. The entire staff was so gracious. The obituary they wrote about me was too kind. It appeared on the last page—where some of the biggest news that didn’t fit on page 1 was placed—under the headline, Pneumonia Claims Edward F. Martin. Globe’s Baseball Reporter Popular in Boston. Stricken While Caring for Wife, Who Died Wednesday Morning.

It was said of “Eddie” that he enjoyed an intimate acquaintance with nearly every fire and police official in Boston. Prior to the death of the veteran “Tim” Murnane, “Eddie” became his protégé, and an apt one he proved. Blessed with a wonderfully retentive memory in addition to an attractive personality, he was popular among baseball men from the outset, and his original style won him the distinction of being assigned to “cover” the last two World’s Series.

By mid-October, Delia and I were two of more than 3,500 killed in Boston during the epidemic, the majority of whom were healthy people between 20 and 40 years old. More than half a million Americans had died. The worst frontline battles in Europe did not see death in anything close to such magnitude.

Over there, Bert Ford was the only New England war correspondent fully accredited with the American Expeditionary Forces and the British armies. He filed stories from the front for International News Services. His dispatches ran in newspapers across the country. Ford saw all the grim horrors of war up close. He had narrow escapes from bombs and shells. He was gassed in the eyes and throat. He found such cruel irony in the twisted reality that the news the soldiers were getting from home was grimmer than what they saw in battle. Ford wrote: “There were weeks when about all the news we received from home concerned the deaths of persons who had been close friends and neighbors.”

For every one casualty in the war, six died at home from influenza.

It was on a Sunday night in a trench in the Argonne Forest that Ford learned about the deaths of Delia and me, as well as Postmaster Murray. Shelling was heavy. Overhead, the clear skies prompted fierce air duels between German and American fliers. Ford crawled into a dugout for cover and to obtain news about the advance of a New York unit. The intelligence officer was Capt. John F. Cronin, a glasscutter who originally hailed from Boston. Cronin’s wife had sent him clippings from the Boston newspapers. That’s how Cronin learned of our fates.

War is hell. I do not know what word exists to capture what war is when life at home is even deadlier. Ford did his literary best to capture this evil duality: “I saw men go into battle after they received word that wife, mother, father, brother, sister or sweetheart had died of influenza. It is difficult to imagine a bitterer ordeal or one that so sorely tested a man.”

Influenza cases in Boston began to decline in mid-October. At midnight on Saturday, October 19, Woodward reopened Boston. Saloons, bowling alleys, theaters, shops, pool halls and the like were free to open their doors again with the start of business on Monday. Schools were reopened.

“It is anticipated that today and tonight will be just like a happy holiday in Boston . . . with great crowds of residents and visitors abroad,” the Globe wrote.

Health care officials cautioned that the city could experience another wave of influenza if people mistook the reopening as reason to let down their guard. Few people paid attention to the warning.

Huge crowds gathered in public venues on the day of the reopening. Lines at movie houses began hours in advance. So many people clamored to see a show that people stood in aisles. Cafés were packed. Roads were crowded with pleasure drivers.

The next day Woodward declared the epidemic over. What happened? How did it end? No therapeutic or vaccine was developed. The strain of influenza simply left as quickly and mysteriously as it arrived. The course of its coming and going bowed to no man but only to the whims of its mutations. In just two months the second wave of the scourge killed 4,794 people in Boston.

There would be a third wave. It was touched off by an event that prompted a huge banner headline in a special morning extra edition of the Globe: WHOLE WORLD IN DELIRIUM OF JOY. Germany surrendered on November 11, 1918.

Word of the armistice first broke just before dawn in Boston. Horns honked, fire whistles shrieked, train whistles blew, church bells tolled and anybody with a telephone heard it jingle incessantly. The noise roused people from their sleep, including Charles F. White of Brookline. White, 62, knew just what to do. He threw on his clothes and ran to the First Parish Church on Walnut and Warren. He banged on the door to get the janitor to let him in.

Back in April of 1865, White was a nine-year-old pupil at a school on Dudley Street in Brookline. His teacher, Susan Hale, announced to them the end of the Civil War. She told them about how Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. Miss Hale closed the school and marched the students over to First Parish, where White and the others joyfully rang the bell.

Fifty-three years after tolling the First Parish bell to celebrate the end of that conflict, White rang the same bell to celebrate the end of the world’s war. The bell rang out far and wide over Brookline, including over Holyhood Cemetery, our final resting place, just two miles away.

In Boston, people poured into the streets for impromptu celebrations. Employees who reported to work were told they were free to go celebrate. Paper and confetti flew from windows.

Gov. Samuel W. McCall ordered the saloons to cease selling liquor at 11 a.m. A parade was quickly organized to start at 2 p.m. It included 10,000 men from the U.S. Army and Navy, more than 2,000 civilians and several hundred yeowomen from the Charlestown Navy Yard. So long was the parade that it took 70 minutes for all of it to pass the governor’s reviewing stand. The crowd lining the streets of Boston was estimated to be in the “hundreds of thousands.”

Celebrations broke out all over the country. Babe Ruth could not partake in the one in Lebanon. He was confined to his apartment because of an injured knee. The great carrier of calamity did not change his stripes once the World’s Series ended. In early October, Ruth had contracted influenza while in Baltimore, but he was lucky enough to suffer from only the far more mild “three-day fever” strain. He sprained his knee a few weeks later during a game for Bethlehem Steel.

The celebrations and huge armistice parade in Boston gathered so many people in tight quarters that they ignited a third wave of influenza. It was not as virulent as the second wave, but the third wave did kill many of those who thought they had escaped danger.

Among the dead in this round of the pandemic were Harry Casey, the sports editor of the Boston Evening Record, and Silk O’Loughlin, one of the best and most well-known umpires in baseball.

Like me, Casey grew up in South Boston. He wrote for the Worcester Telegram for five years before joining the Record. Casey had been ill for two weeks, but he kept reporting to work until finally he grew so ill he had no choice but to stay home. By then it was too late. He died Dec. 17. He was 32 years old and left behind a wife.

O’Laughlin died in Boston three days later. He was known for his long, loud, drawn-out calls (“St-ee-rike tuh!”), an ornate diamond ring and his insistence that he never missed a call, even dating to his training as a minor league umpire. One day a minor league player in Worcester was examined by a doctor after getting hit by a pitch that O’Laughlin ruled did not hit him.

“Your arm is broken,” the doctor said.

“No. My arm can’t be broken, Doc,” replied the player.

“Why not?”

“Silk O’Laughlin told me that ball never touched me, and Silk claims he never made a mistake in his life.”

After the early end to the 1918 season O’Laughlin worked for the Boston District of the Department of Justice in a group called the Plant Protective Military Intelligence. He investigated suspicious persons to protect munition works and shipbuilding plants from German spies and sympathizers. Both O’Laughlin and his wife grew sick. Only she survived. O’Laughlin was 46. So renowned was O’Laughlin that his death was front page news as far away as Hawaii. His funeral was said to be one of the largest ever held in Rochester, N.Y., his original hometown.

Another spike of cases occurred in Boston around Christmas, as people gathered around the holiday. That spike, too, was not as severe as the one in September and October. By February 1919 the great influenza pandemic was over. It ended as suddenly as the war. Baseball, which we thought could be shut down for years, would go on uninterrupted in 1919, though because of the Black Sox it was far from unblemished that year.

I look back on that 1918 World Series as an event made possible by a fortunate bit of timing. It was only by order of Secretary of War Newton D. Baker that baseball ended its season on Labor Day, about a month early. That World’s Series is the only one on record played entirely in September. It ended just as influenza was jumping from navy receiving ships and army cantonments to civilian life in Boston. But for that edict from Baker, the Red Sox would have been playing the final week of the regular season when Woodward put Boston on lockdown and banned public gatherings. The World’s Series might never have been played.

Almost all the Red Sox players left Boston after September 12 to go home to essential jobs or military service—just as the epidemic was about to explode in Boston. The Babe and Helen left their country home in Sudbury, Mass., 22 miles west of Boston, for Lebanon.

Some were lucky. Many were not, including Delia and me. Such is the indiscriminate horror of a pandemic against which we have little to no defense. Boston, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh were hit hardest. San Francisco did best at limiting the mortality rate. The evil that was influenza came and left without warning.

Lack of control bothers humans. As is happening now, in 1918 much second-guessing and blaming took place. People blamed Woodward for not acting quickly and aggressively enough. Woodward blamed poor social etiquette, including sneezing, coughing, “forcible talking” in crowds and dirty dishware in restaurants and ice cream parlors. The federal government took no centralized role in coordinating interventions.

Over a 24-week span influenza killed 675,000 Americans—about 4,000 per day, nearly triple the rate from this COVID-19 pandemic. More Americans died in the 1918 pandemic than in World War I (116,516), World War II (416,800), the Korean War (33,686) and the Vietnam War (58,220).

The estimate of worldwide deaths from influenza in 1918 begins at 50 million and goes as high as 100 million. About half a billion worldwide became infected—or one out of every three people on the planet.

I pray you will be free from the grip of COVID-19 soon. You must believe there will be a day again when you can fully live, not merely survive, and when there is room, even a need, for the frivolity of baseball.

Life, like contagions, can choose its own course. Never was I happier than on November 8, 1916, when I saw Delia in her gray satin wedding dress, clutching a bouquet of roses, as she walked down the aisle of St. Eulalia’s to be my beautiful bride. Every possibility in the long life I imagined was a happy one. Instead, within two years, America went to war; the deadliest pandemic ever to hit mankind raged across the planet; and my mentor, my father-in-law, my wife and myself all would be dead.

This is why I wanted to tell you my story. The lesson is not how you defeat a deadly virus. It is an insidious, invisible foe that cares not about borders, class, ethnicity, government, plans or expectations. It does not conform to the order we think we can impose on the natural world. The lesson to take from this lack of control is to cherish every moment, even the small ones.

Exactly two months after the Red Sox won the World’s Series at Fenway Park, the dome of the Massachusetts State House in Beacon Hill was lit for the first time in 19 months. It had gone dark once America entered the war out of fear of imminent enemy air raids. With the Armistice, the light returned.

Charles Bulfinch’s masterpiece of Federal architecture never looked better in its 120 years than on that night of September 11, 1918, not even when Oliver Wendell Holmes was so inspired by its physical, civic and psychological heft that he dubbed it (and by extension Boston itself) “The Hub of the Solar System.” Fear had ended. Optimism, as captured in the form of light, had returned.

More importantly, what a pandemic teaches you is not to wait for happiness from weddings, World’s Series, armistice days and any such major milestones in life. Find it in everyday moments. Appreciate the preciousness of a child’s laugh, the dedication of health care providers and first responders, the empathy of a community, and especially the shared love of family and friends. Once you do, no matter amid the best or worst of times, you understand the Hub of the Solar System is not a place but the love that lies within.

Your Dearest Friend,

Edward F. Martin