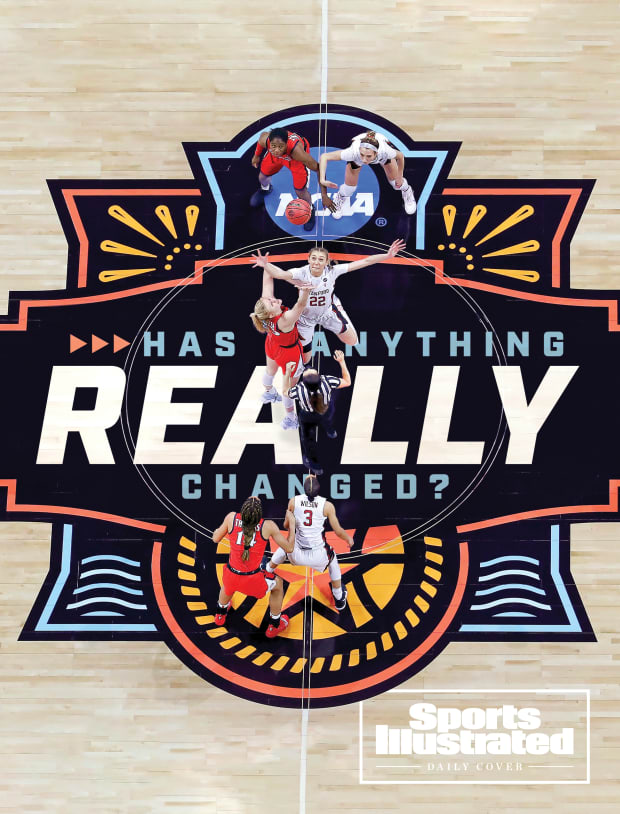

Advocates and NCAA administrators still disagree about what needs to change in college hoops.

The NCAA has a list of everything that will be different about the Division I women’s basketball tournament this year. It’s the smallest entries on the list that are the most remarkable.

In a presentation given to media in early March, NCAA basketball leadership was sure to mention some changes that were almost comically specific: When the men get a gift box that includes a notebook, a sleeveless hoodie and a baseball cap, the women will now get a gift box that includes a notebook, a sleeveless hoodie and a baseball cap. And: The women will have a yogurt bar and a pasta station to match the men’s yogurt bar and pasta station. At the Final Four, the women will now have lounges that include a Ping-Pong table, three big-screen televisions and 28 pillows, just like the men at the Final Four.

The mention of that 28th pillow was as detailed as it was damning.

Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin; Elsa/Getty Images

“On the one hand, you’re like, Thank you. You know, the players don’t have to feel less-than in those areas anymore, so you do want to say thank you,” says UCLA women’s basketball coach Cori Close. “And on the other hand, you want to go, Really? Like, really, it took a major crisis and millions of dollars spent on analysis to come up with, We need to treat them the same?”

A year after the NCAA met with controversy for its disparate handling of the men’s and women’s tournaments, it announced a suite of moves designed to change the experience. That comes after significant outcry and an independent gender equity review by a law firm. People around the game hope this is only the start: They’re glad to see the swag bags and lounges will now be the same. But there are far bigger organizational topics left to tackle.

Chris Pietsch/The Register-Guard/USA Today Network

This year does have some bigger changes in store from the NCAA: The women’s tourney has expanded to 68 teams, as the men’s did back in 2011, and women’s games will finally be able to use the “March Madness” branding. But that still leaves plenty of questions about structural issues with the tournament.

Those questions stand out to a coach like Close. She is the president of the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association—putting her at the helm of one of the biggest groups that has been pressing for change over the last year. The coaches had long felt there were striking disparities between the men and women. But those had never been displayed as clearly as they were in 2021, when both tournaments were forced into bubble environments by COVID-19, and the differences were impossible to ignore. As a result, the coaches launched an initiative called Our Fair Shot, designed to highlight elements of the women’s game they felt were ripe for significant change.

A year later, most of the initiative’s concerns remain unaddressed.

The NCAA insists that its recent moves represent only the beginning of its plans for women’s basketball: “There's more to do, and we look forward to doing much of that after this year’s championship with more time and more opportunity to plan,” NCAA senior vice president of basketball Dan Gavitt said at that same media presentation. But there are still questions around what that will actually mean—namely, whether it will involve more of the moves recommended in the gender equity review conducted by the law firm Kaplan Hecker & Fink, and if so, which ones and when.

Several of those recommendations center on television rights. The men’s tournament has a massive deal with CBS and Turner, whose latest extension was for eight years and $8.8 billion. No one is suggesting the women’s tournament would land a similar figure. But it’s never had a chance to try to land anything: rather than standing alone as its own media property, it’s part of a package with 28 other NCAA championships, such as wrestling, lacrosse and gymnastics. ESPN holds the rights to that package on a deal that runs through 2024 with an average annual payment of $34 million.

The Kaplan report found that women’s basketball would likely fetch an annual rights payment on its own between $81 million and $112 million.

In other words: The report claims that the NCAA has potentially left tens of millions of dollars on the table by neglecting to recognize the earning power of the women’s tourney. There is little room for it to grow as its own product with its value tied to so many other sports. (When the NCAA initially responded to the scandal over the tournament last year, it claimed the discrepancy between the men’s and women’s tourney budgets was because the men brought in money while the women annually lost $2.8 million—but it backed up that number by saying that the television rights payment brought in by the women was just $6 million. Some outside experts questioned how the NCAA got to that number when the women’s tournament is one of the biggest championships in that group of 29, and therefore might represent a much larger slice of that $34 million, let alone a much larger figure overall if sold on its own.) All of that leaves a sense that the picture here could look very different if the NCAA committed to breaking the women out of the package and taking them to market on their own in 2024.

“The NCAA needs to commit—not only are we going to allow the women’s tournament to be brought out, but we’re going to leverage it, market it, try to make it the best,” says Close. “That would show that the NCAA really values the marketability of women, and that it's not just a cause, but it's a product and an asset worth investing in.”

Gavitt acknowledged that with women’s basketball in the current package of championships,“those rights are likely undervalued, and quite possibly significantly undervalued.” But he would not say whether the NCAA had committed to bringing the women’s basketball tournament to market on its own in 2024, rather than keeping it grouped with the other sports, saying only that his team had “started some strategic planning internally on how to approach that.”

Other unaddressed recommendations from the report include the leadership structure of the NCAA. The head of men’s basketball is Gavitt, who reports directly to NCAA president Mark Emmert. The head of women’s basketball is Lynn Holzman, who reports directly to … Gavitt. “Although this structure, on its face, should not necessarily disadvantage Division I women’s basketball, many stakeholders report that, in both practice and perception, women’s basketball essentially reports, and is subordinate, to Division I men’s basketball,” reads the Kaplan report. Both Gavitt and Holzman said their teams worked together more in the last year than they ever had previously and finally began having regular joint meetings. But the NCAA had no update on any potential changes to the larger structure.

And the report also included some suggestions of big-picture ideas. What if the men’s and women’s Final Fours were held in the same city—one big weekend of the best in college basketball? Per the report, “holding a joint Division I men’s and women’s basketball Final Four in one location over a single weekend would be the best, and likely the only way to reduce the existing gender inequities seen in Division I men’s and women’s basketball.”

The NCAA said it is potentially open to the idea later but not looking at it right now.

“We really just felt that we wanted to see how these upcoming enhancements are going to impact the game and the growth of the championship,” says Duke athletic director Nina King, who serves as chair of the Division I Women’s Basketball Committee. “We didn’t feel like we wanted to, at this point, implement a change in the format for the Final Four until we see again how these enhancements are going to play out.”

There’s an understanding that some of these changes are ambitious and could not be implemented overnight. But there’s also a desire to land commitments that keep last year’s momentum—even with all of the structural obstacles detailed in the report, the women’s game is growing, and this, coaches think, is the moment to jump in and plan.

“The time is now,” Close says. “Not only because it’s right and we should have done it a long time ago, but because it's a good business decision—a good asset worth investing in.”

Elsa/Getty Images

The numbers support the idea that this is a time of growth for the game—a time when investment makes sense. Last year’s Final Four was the most viewed in a decade. This year’s regular season suggests that this one might be even better: Through early February, average viewership for women’s college basketball was up 46% from 2021. Even the tourney selection show—which had traditionally been held on Monday, but was moved this year to Selection Sunday, the same as the men—saw a big spike: 1.1 million viewers, representing a 160% increase from 2021. And the advent of name, image and likeness deals have seen women’s basketball players outearn athletes from every sport other than football.

“We talk about being bullish on women’s basketball,” says Holzman, the NCAA vice president for women’s basketball. “All the data does represent that. There's many reasons to continue to be bullish, and really invest and continue to have a championship that is representative of that growth.”

The hope for coaches and athletes is that the NCAA is ready to follow through.

“That’s the thing that's interesting that I think we're going to learn in the next year,” Close says. “Is this just about ticking the boxes to avoid more bad press? Or is this about, no, how do we move the needle? How do we get better here?”

More March Madness Coverage:

• Sleeper Picks for Women’s NCAA Tourney

• SI’s Expert Brackets for Women’s March Madness

• Upset Picks and Fearless March Predictions