What happens when one of baseball’s most significant figures gets inducted against his wishes after he dies?

Welcome to The Opener, where every weekday morning you’ll get a fresh, topical column to start your day from one of SI.com’s MLB writers.

Peter Miller believes his father deserves his spot in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The first executive director of the players’ union, Marvin Miller was elected to the Hall in December 2019, the eighth time that he had been placed under consideration, and to Peter, the recognition seemed “long overdue.” But when Miller is finally inducted Wednesday—in a ceremony delayed a year by the pandemic—Peter will not be there. It’s not that he wouldn’t like to be. This is not a protest, he wants to make clear, or an act of bitterness. In fact, it wasn’t really his choice to begin with: It was his father’s.

In the last years of his life, Miller asked to be removed from consideration for the Hall, and before he died in 2012, he made clear that if he were ever inducted, he would prefer his family not participate in the ceremony. Miller had come to view the selection process as a “farce,” as he wrote in his request to be taken off the ballot, and even in death, he did not want anyone to get the impression that he had felt otherwise.

But the Hall and the Baseball Writers’ Association of America kept Miller eligible for induction. On Wednesday afternoon, he’ll be enshrined in Cooperstown in a class that also includes Derek Jeter, Ted Simmons and Larry Walker. And for his son, Peter, the ceremony is both an achievement that he feels has been deserved for decades, and an occasion that he feels obligated to sit out.

“In other circumstances, I’d have liked to be there. If this was done during his lifetime, I’d have enjoyed it, if he had wanted it,” Peter says. “After all, it’s a great event. … And I don’t want to take anything away from that by the particular conditions that have been placed on me. I just have to follow my father’s wishes on that.”

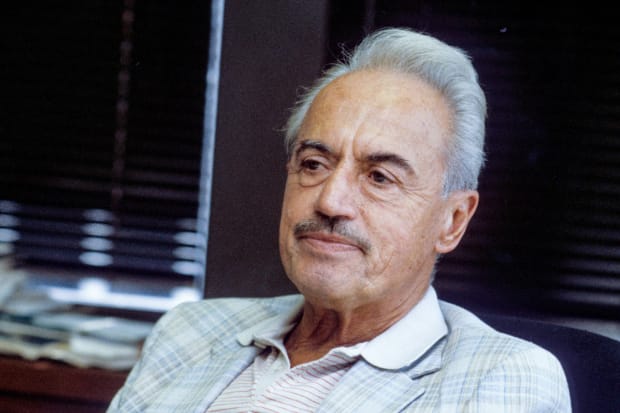

Tony Triolo/Sports Illustrated

Miller’s candidacy for the Hall was a battle for years. The historic nature of his work is clear: Under his leadership from 1966 to '82, the players won free agency, negotiated their first collective bargaining agreement and secured a future for the pension fund, among other milestones. But there was some pushback to the idea that Miller qualified as a “baseball executive,” as the election rules required, and the Hall’s veterans committee at first declined to even consider his name. It was a decision that ran contrary to the desires of many players: In 2000, The New York Times asked Hall of Famers if they felt that Miller should join them in Cooperstown, and the collective answer was a resounding yes.

That he hadn’t already been inducted was a “national disgrace,” said Tom Seaver.

“Miller should be in the Hall of Fame if the players have to break down the door to get him in,” said Henry Aaron.

“Marvin Miller taught us all to stand up for ourselves. It’s time we took the responsibility and stood up for him,” said Brooks Robinson.

Finally, in 2003, the committee decided to consider Miller. But many of the committee members were executives—the same management that Miller had battled against with the MLBPA—and so it was no great surprise that they chose not to elect him. They did the same in 2007 and once more in 2008. “Essentially, the decision for putting a union leader in the Hall of Fame was handed over to a bunch of executives and former executives,” Jim Bouton fumed to The Village Voice. “Marvin Miller kicked their butts and took power away from the baseball establishment—do you really think those people are going to vote him in? It’s a joke.”

That was when Miller formally requested that his name be removed from consideration for Cooperstown. He disliked unfairness in any form, and at this point, the committee process struck him as so unfair as to be entirely pointless: “I find myself unwilling to contemplate one more rigged veterans committee whose members are handpicked to reach a particular outcome while offering the pretense of a democratic vote,” Miller wrote in his 2008 letter to the BBWAA. “It is an insult to baseball fans, historians, sports writers and especially to those baseball players who sacrificed and brought the game into the 21st century.”

Miller continued to come up for consideration and continued to be shut out of the Hall. His stance never shifted. When Peter last asked his father about the subject, two days before he died of liver cancer at the age of 95 in 2012, he maintained that his feelings were the same: He did not wish to be in the Hall of Fame, and if the committee ever voted him in, he did not want the family to participate after his death. (His wife, Theresa, had passed away a few years earlier, leaving Peter and his sister, Susan, who indicated after the election that she would similarly decline to attend the induction ceremony.)

The decision was, in a sense, a capsule of Miller’s principles and how he viewed the legacy of his work.

“He wasn’t interested in fame,” says Peter, reached by phone from Japan, where he has lived for decades. “A lot of people didn’t understand that that isn’t what drove him. What drove him was the solidarity of a union and free agency—freedom. That’s what he cared about. He really did not seek personal fame for himself, and that’s, I guess, another reason that he didn’t seek induction to the Hall. He didn’t want to make it all about himself.”

Which all makes for somewhat unusual circumstances now: Who, after all, doesn’t want to be a Hall of Famer? The Hall has plenty of experience with inducting candidates posthumously, but it has not ever had to deal with someone who was explicitly clear about not wanting to be inducted in life, with wishes that his family respect that desire in death. But Peter feels at peace with the way that it has played out. He’s spoken with representatives of the Hall several times since his father was elected, and rather than discomfort around the situation, he feels there is a mutual understanding.

“They’ve been very cordial and diplomatic,” he says. “They understand completely where I’m coming from, which is that my father’s instructions—from the time he wrote that letter in 2008 right up until the time of his death—were that no member of the family should participate in any induction, should it occur.”

In the end, Peter says, he finds the continued strength of free agency a more fitting monument to his father than any plaque. He thinks that a more appropriate home for his father is the National Portrait Gallery—a public institution, open for free to all, where Miller’s picture was added in 2019 to hang alongside not just baseball icons but other sports leaders, labor activists and more. Yet he still thinks his father deserves this spot in Cooperstown, and he might tune into the induction ceremony Wednesday after all. Particularly with the tributes scheduled to the Hall of Famers who have passed away in the last two years, including several who worked closely with his father through the MLBPA, he’d like to see it: Miller requested only that the family not participate, he says, not that they refuse to watch altogether.

“He didn’t say anything about not watching it online,” Peter says with a chuckle, noting his father’s disinterest in computers. “So maybe I will.”

More MLB Coverage:

• How MLB Squashed Its Fake-Memorabilia Problem

• How Do We Make Sense of the Mets?

• When the Mets’ Woes Are More Insidious Than Just the Jokes

• Who Is the Next Miguel Cabrera?