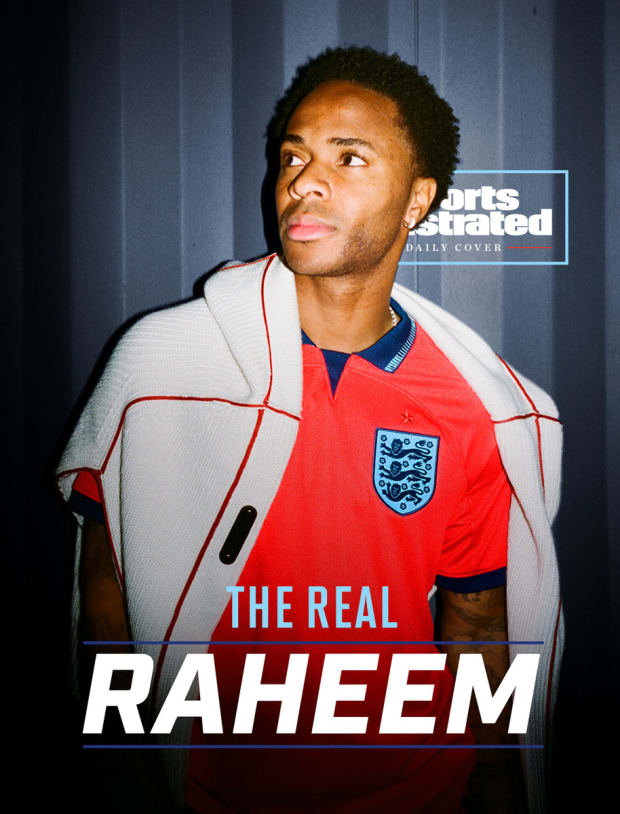

The boy from Brent grew up in the shadows of Wembley Stadium long before he starred under its arch. But fame hasn’t turned him into what U.K. tabloids would have you believe.

Raheem Sterling is back home. Not just in London, where he acted as his own agent in a £45 million ($54.1 million) summer transfer to Chelsea. Not at Wembley Stadium, where he is the most experienced England player at just 27. But in Brent, the bustling borough where he is a legend.

On a warm Sunday afternoon in September, the Boy from Brent, as he is affectionately known, is in a stuffy van ferrying him around his old neighborhood, where he says “trouble is always knocking.” There is a camera in his face for a day-in-the-life documentary, but really the story is trying to capture his life in a day, and the compressed spotlight is clearly making Sterling uncomfortable. He often seems at odds with his celebrity—some would call that humility—despite spending the last 10 years as one. He cringes at being called a role model. But such is the shine of being the Star of Wembley.

And when producers ask him to look out the window and reminisce, to tell stories and point out boyhood hangouts, he quips that they are not even in his neighborhood anymore. The car falls silent.

Courtesy of Karan Teli on behalf of Playmaker Films

It is abundantly clear that Sterling won’t be what people want him to be to fit their own narratives. He will not fake an existence that he has spent so long crafting. It’s hard to blame him after years of intrusive attacks from British tabloids that highlighted his spending habits more than his goal count (159 goals for club, 19 goals for country so far) and after being subjected to racist abuse in the stands and on the street—he once recalled the story of a man who headbutted him and called him the n-word on a random street in Liverpool.

But not far down the road is the hotel where an immigrant child from Jamaica would help his mother clean rooms at 5 a.m. before school. And the field where players from an opposing youth team once waited to jump a future four-time Premier League winner outside of the gates because his talent made them look like fools. Now, it’s all chic bars and corporate hangouts trailing down Wembley Way.

“Wembley before was just the stadium and not much else around,” Sterling says as he looks out from the van. “There were loads of older buildings around the stadium. Now every time you come back there’s three or four or five or six different, brand-new modern buildings. It’s incredible to see—a lot of things that I wish was here when I was younger.”

Now Sterling is back home, providing what he wished he had as a kid: opportunity, a helping hand, a chance to be seen and heard above the London noise.

After circling the area, the van finally stops at the Bridge Park Community Leisure Centre in Brent. From the parking lot, you can see the famed Wembley arch at England’s national stadium. Sterling grew up in its shadow, playing with his friends at the center. At the moment of his arrival, it is simultaneously hosting a rollicking church service, a roller derby, a pickup game of indoor soccer, some form of martial arts practice and a dance rehearsal.

Wearing sweats and a hoodie, Sterling bounces around and ends up in a dance studio lined with mirrors and a worn parquet floor. A teenage dance troupe has been expecting Sterling, but they still all beam at him when he enters the studio.

For the documentary, Sterling asks the girls about growing up here, about their plans and aspirations. And when they talk about going to school to become social workers and lawyers to give back to their community in Brent, Sterling is in awe of them. Moments later, he gets pulled into their dance routine. “I hate dancing!” he yells through a laugh, trying to follow their choreographed steps. Maybe it could be a new goal celebration, or maybe it’s just Sterling’s way of looking out of the window and reminiscing.

As a crowd gathers outside the community center—word travels fast on the Brent grapevine—there is no pretense, no facade. He is both the Boy from Brent and the Star of Wembley, a rare moment where both personas seem to meld rather than clash. It is a portrait of the harmony that so often evaded him—in London, at Wembley, around Brent.

Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

As he tours the community center, Sterling comes across a Ping-Pong table. A group of high school students are huddled around it and one is calling himself the king of the table as he burns through the competition. Sterling hears this and calls next, and the teens let out an “Oooh” to initiate the challenge. Sterling absolutely destroys the kid, three games to none, and he talks light trash the entire time.

“I thought this was your table?” Sterling continues to say between points, and in the heat of the moment he’s not exactly laughing.

But then Sterling pulls the teen aside for a chat. They joke and hug, and later, as Sterling leaves the center, the boy is in a scrum of people waiting outside as Sterling signs autographs and takes pictures. Sterling refuses to leave until everyone is happy, even as the crowd grows, even as the documentary’s schedule falls further behind and more time in the stuffy van awaits. Elderly women with Jamaican accents pull him aside to talk about the island, and he listens and laughs. Kids ask him for selfies, and he doesn’t really need to pose because he is always smiling.

One can’t help but wonder which moment the tabloids would feast upon, and on the subject of tabloid coverage, as the van leaves the community center, Sterling points to a Smart car in the parking lot that he gave to a friend.

“You know that used to be mine when I was at [Manchester] City?” Sterling asks. It’s astonishing for the fact that a major tabloid headline once claimed that he bought a car for every day of the week, Bentleys and Range Rovers and Mercedes. It was all part of a campaign to make him look “flashy” and to paint him as something that white players were not subjected to.

“I did add suicide doors to it though,” Sterling admits, and the van erupts in laughter.

The car headline was one of the lighter backpage dramas for Sterling. They often commented on his dating life, speculated on how many kids he had and scolded him for how he spent (or didn’t spend) his money. When he moved to Manchester City in 2015, Sterling was the most expensive English transfer in history. By the time he turned 21, Sterling already had 20 appearances for the England national team, a World Cup appearance and a Golden Boy trophy as the best young footballer in Europe.

Karan Teli on behalf of Playmaker Films

Never before had a Black man playing for England had so much sustained success from such a young age. Yet, the media coverage of Sterling was also unprecedented.

When a video surfaced of Sterling at his mother’s home, the headline read: £180,000-a-week England flop Raheem shows off blinging house he bought for his mum—complete with jewel-encrusted bathroom—hours after flying home in disgrace from Euro 2016.

When he flew home from vacation on a budget airline: Manchester City star Raheem Sterling earns £200,000-a-week... but takes £80 easyJet flight back from holiday.

When a photograph showed a picture of the assault rifle tattoo on his shooting foot, which Sterling said he did as a reminder to never touch a gun after his father was “gunned down,” one tabloid likened him to glorifying gun violence: Raheem shoots himself in foot.

Clive Ellington, Sterling’s childhood mentor, says he remembers being at a cafe with Sterling after a photo shoot at Wembley, and over Sterling’s shoulder he could see a newsstand filled with obscene headlines.

“He just turned around, looked at the newspaper and turned back again,” Ellington says. “Didn’t want to take it out or anything like that. And that’s when I told myself: ‘That’s maturity,’ because you can’t believe your own press.”

The coverage lasted for years, and it ramped up during major tournaments for England. Apart from the constant obsession with Sterling, the headlines were often steeped in racist language. They labeled him “the Prem Rat of the Caribbean” and “Footie Idiot,” and told him “Don’t Be Greedy” when he was in talks over a new contract while at Liverpool.

“In my day-to-day life it didn’t affect me,” Sterling says. “I think there were times it was affecting me when I was going to the national team. I think that’s the only time I actually felt like it affected me—on a day-to-day, it didn’t affect me.

“But of course like anything over a certain period of time, something of that magnitude can take a toll on someone. In my case it did, but I learned how to deal with it and I overcame it.”

Sterling rarely reacted to the coverage, but he responded after being racially abused during a match against Chelsea in 2018 that saw five fans suspended and one fan banned for life. In an Instagram post the next day, Sterling brushed off the attack; rather, his focus was on the insidious coverage that “fuels racism.” He juxtaposed headlines written about two young Manchester City teammates who had purchased houses for their mothers and called for a change that would “give all players an equal chance” in the way they are covered.

One about Tosin Adarabioyo reads, “Young Manchester City footballer, 20, on £25,000 a week splashes out on mansion on market for £2.25 million despite having never started a Premier League match.” Months later, one about Phil Foden simply states, “Manchester City starlet Phil Foden buys new £2m home for his mum.”

After spending years as a tabloid target himself, Sterling was praised for addressing one of the many roots at the core of racism in soccer as he linked the coverage and language to the racial abuse he faced. High-profile pundits and journalists backed him publicly; stars in the sport like Megan Rapinoe and Rio Ferdinand lauded his courage.

It was a clear turning point for Sterling, Ellington says. The star went on to have a career year for England, scoring eight goals in nine games in 2019. And by England’s next major tournament at Euro 2020, the sensational headlines had mostly disappeared.

Catherine Ivill/Getty Images

“Unfortunately, it was just purely down to color,” Ellington says. “Sometimes if your face don’t fit on this particular model that they have within the media in terms of the poster boy, then they’ve got to find a way of dismantling that and unfortunately, sometimes it was a matter of, well, ‘We need to find a story’ or write him down to kind of say, ‘Know your place.’”

Last year, Sterling received an MBE (Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) from Queen Elizabeth II for his work in anti-racism campaigns. A few months later, he unveiled the Raheem Sterling Foundation at his former secondary school in Brent to help improve social mobility and educational opportunities for children in Brent, Manchester and Jamaica.

But Sterling won’t let you call him a role model. Once again, he won’t let others project a title onto him—good or bad. It’s his way of making sure the Star of Wembley doesn’t get lost in his own glow.

“I just go about my day-to-day in my career and focusing on doing the right thing, and that’s all I’ve ever tried to do,” Sterling says. “If in somebody else’s eyes it’s seen as a good thing then so be it, but I don’t look at it in that sense. … You’ll have to ask them.”

Ellington remembers the first day he picked Sterling up from school. The two had met when a referral arrived for Ellington, who worked for a mentorship program in the area.

8-year-old, moving from school to school, father killed in Jamaica.

Ellington, 56, would usually work through a sort of script to get to know the mentee: What do you like? What are your hobbies?

“Football,” Ellington says of Sterling’s response.

What do you want to be when you get older?

“Footballer.”

Whether it was driving through Brent in a van filming a documentary or driving home from school, it is obvious that Sterling is not someone who followed a script.

“There was no Option B. ‘But if you can't make it [as a footballer]?’ No answer,” Ellington says. “If you tried to talk about anything else, he would be very limited in his responses back to you. I said to him: ‘You got to think about other things around. You could be an engineer, scientist.’ Nothing. I remember the road we were going down—[he] wouldn’t say a word. He wouldn't put any other options on the table to talk about anything else.”

Faced with only one solution, Ellington took Sterling to train with Alpha & Omega CF FC, a grassroots club that Ellington still runs. Within a few years, Sterling had signed with west London side Queens Park Rangers over Arsenal, after his mother convinced him that a smaller club would be more invested in his growth. At 15, Sterling made a high-profile move to Liverpool. At just 17, he made his Premier League and England senior national team debut—all sparked by that car ride home from school.

“Clive came into my life and ultimately changed me for good,” Sterling says.

Sterling credits people like Ellington with inspiring the mentor-based approach to his foundation. And it’s the people in Brent who constantly feature in the narrative Sterling portrays to the world.

When Sterling joined QPR, his mother would send his sister Lakima with him to take three buses across London to training. Every day, the same three buses, round trips that often stretched past 11 p.m. It was west and northwest London that carved the path, and so he honored that journey—and his sister—on his New Balance cleats, which feature the same retro design as the felt seats on London’s older double-decker buses.

New Balance

Wembley Stadium always loomed in the background, and Sterling could see the looping arch as a kid while playing from his garden. So to say he plays in his own backyard when taking the field at Wembley often takes on a literal meaning.

“When I used to take the bus, coming from training from QPR, you used to see the arch way over you,” Sterling says. “Everytime you go back to Wembley, it’s a surreal feeling, a moment to give gratitude. Like you’ve always pictured yourself playing there but never understood that it was possible.”

It was in his own backyard where Sterling nearly led England to European glory. In England’s first four games of Euro 2020, Sterling scored three of the team’s four goals—all at Wembley, including the breakthrough goal in the round of 16 against Germany. While England lost the Euro final in a penalty shootout, Sterling had emerged as a star.

In Qatar, he won’t have the comforts of home that Wembley provides. But the pressure of playing for the English national team will always follow. The Three Lions have not won a major tournament since the 1966 World Cup, and they nearly tasted glory by reaching the semifinals of the 2018 World Cup and the final of Euro ’20. Couple that with an incessant media spotlight and a ravenous fanbase, and every tournament for England becomes a pressure cooker—the expectations for Qatar end with a World Cup trophy. But first, England must survive a tough group that features the United States, Wales and Iran.

Sterling’s eyes light up when he’s told that England’s showdown with the U.S. on Black Friday is widely expected to break television records for the most-watched soccer game in U.S. history: “That’s gonna be really interesting—I’m looking forward to that.”

If England makes it to the quarterfinals, Sterling will turn 28 in Qatar. But he will gladly delay birthday celebrations by a few weeks if England brings home a World Cup trophy after so many close calls.

“If you don’t win something, it’s a disappointment,” Sterling says. “But now we’ve reached the latter stages of these competitions and know what it takes to do it. So going into this competition, I think it'd be no different and we just need to focus on that and try to go one better.”

While much of London hums, it’s a quiet September Sunday in Brent, and it’s especially quiet for Sterling. Premier League matches have been postponed after Queen Elizabeth II’s death, and there is no Chelsea match against Fulham. Helicopters circle central London as thousands make their pilgrimages to Buckingham Palace with flowers and mementos, but at Ark Elvin Academy there is a focus on meditation.

From the steps of his former secondary school, Sterling stares at the new buildings surrounding the area, all glass and sleek metal, a vision of progress. On the day of the foundation’s inauguration, Sterling and academy students made the one-mile walk from school to Wembley Stadium in a powerful reminder of his journey. Wembley, something that is often so inaccessible to the public outside of matchday, had opened its doors to its star from Brent and the schoolkids just a decade behind him.

Sterling describes his time as a student as “not settled in school, always kind of kicking up a fuss.” As a child, he was sent to a behavioral school partly for his unwillingness to participate and trouble processing his emotions before coming to Ark Elvin. Now, he returns to check on a meditation room that he is building for students.

“It’s something that I’ve grown to love and would’ve benefited from,” he says. “All the noise and all the things that goes on in school, to have a place that you can actually go reflect and get to a calmer place and get back to feeling good parts of yourself is really cool to see.”

The school has the newly renovated feel of a Silicon Valley startup, and Sterling’s name is everywhere. On the wall in the main hallway, his England jersey is signed and framed and dedicated to the school. It’s a shirt that carries so much weight, often the hope of even-year English summers that will now be transposed onto this fall.

Eddie Keogh/The FA/Getty Images

No one in England’s 2022 World Cup team has worn the shirt more than Sterling. And perhaps no one in the team has felt the all-around pressure like he has, but to Sterling, the thrill of wearing the shirt has yet to burn out.

“I don’t feel that [pressure of the England jersey],” Sterling says. “I think every time you see the shirt it’s a great privilege, so it’s more excitement than anything. It’s a moment that every time you put the shirt on, it’s like making a debut again. That’s the feeling I can describe. It’s always an incredible, enjoyable moment, and I think that’s what drives me is that every time I get called up, I know I’m gonna get to put that shirt on again.”

As he leaves the school, an elderly man in an oversized blazer walks up to Sterling, and the Chelsea star recognizes him immediately: “This is the same caretaker that was here when I was here!” There is no crowd here, just them and the empty school.

Sterling asks for the man’s name and personalizes an autograph. They pose for a picture and the caretaker asks Sterling to join him at the nearby Hindu temple. Sterling not only agrees but asks for operating hours and when he can visit.

There is still one more segment of the documentary to film before dark, and everything continues to run behind schedule. But he is chatting about the borough, and there is always time for the borough. To the caretaker, Sterling is the Star of Wembley, but in that moment, Sterling basks in being a boy from Brent.