Unpacking the cross-generational allure of a wallet-sized paper rectangle that shaped the collecting industry and helped grow the game of baseball.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

In early January, the most expensive baseball card ever sold went on a 3,700-mile journey to meet its new owner, ensconced in a comically large zip-tied tarpaulin sack that could have doubled as a prop for a mall Santa.

The card departed from a broker’s bank vault in Portland, under the watch of private security, and boarded a nine-hour flight to San Juan. Two armed guards then drove it from the airport to a gated beach community. At last it reached the home of 35-year-old Rob Gough, who hustled out to greet the armored truck, produced his ID, signed for the shipment and set about unpacking a nesting doll of additional protections. Inside the sack was a cardboard box, inside of which was a smaller box, inside of which was a foam-padded case containing a fireproof bag containing an authenticated plastic-slab holder containing the card itself.

“I’ve got goosebumps,” Gough said, narrating the big reveal as his girlfriend recorded the arrival on her phone. “Look at this. Beautiful. . . . Isn’t that crazy? Five-point-two million bucks.”

For Gough, an actor-producer-entrepreneur who owns a CBD company, the path to this record purchase began in the early 1990s, when he would score cheap baseball card packs from an Indianapolis comic bookstore and sort their contents, by team, into binder sleeves. Over time his interests turned to other life pursuits, but he was lured back last summer as the sports collectibles industry boomed during the pandemic, and he hit the market hard, dropping $10 million on hundreds of rare cards last August alone.

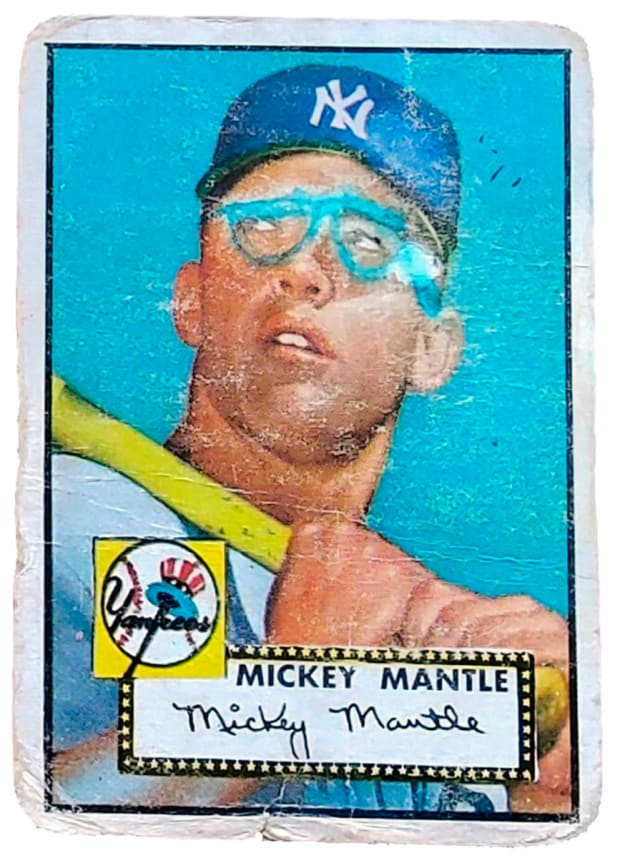

Eventually he mined his old collection, which his mother had saved. “Most of it was junk—cost more to mail it to Puerto Rico than the value of the cards,” he says. But out of this flotsam of his youth, one card gave Gough pause. It was only a reprint, issued long after the original and therefore much less in demand. Still, the simple act of again glimpsing a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle—the bright-yellow bat, the crisp aqua sky, the shadow cast across the Mick’s face by his Yankees ballcap—proved powerful. “It brought me back to thinking, even as a kid, that this was the card,” he says.

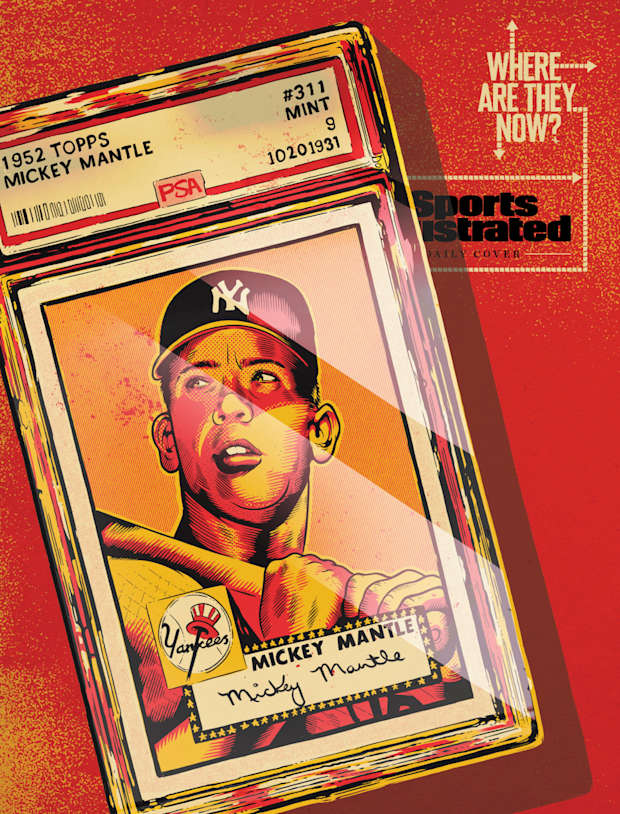

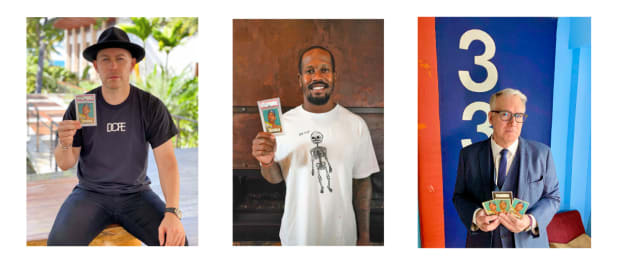

Trawling eBay and tracking down private sellers, Gough soon began to gobble up ’52 Mantles. By the end of 2020 he owned a modest PSA 4 (as per the 10-point scale set forth by the industry’s preeminent grading company, Professional Sports Authenticator) that he bought for $43,000; a PSA 5 for $50,367; and a PSA 8 for $385,255—not to mention the $77,500 PSA 6 that he flipped at no markup to deejay friend Steve Aoki. But these all paled in comparison to the mint PSA 9 for which Gough negotiated through a broker and wired all $5.2 million in one chunk around New Year’s, shattering the mark set the previous summer: $3.9 million for a signed mint ’09 Bowman Mike Trout rookie card.

“I didn’t buy [my Mantle] to flip it,” says Gough, who after savoring its presence for two weeks returned it, along with the rest of his collection, to the vault for safekeeping. “I bought it to own the Mona Lisa of sports cards. There’s nothing more iconic or more beautiful.”

The ’52 Mantle is many things. Even if it’s far from scarce, and even though it’s not a rookie card (Bowman printed that in ’51), it remains, for many card zealots, one half of a two-man Mount Rushmore, alongside the T206 Honus Wagner issued by the American Tobacco Company shortly after the turn of the 20th century. Or: “It’s the jewel,” says San Diego card dealer Kit Young. “The holy grail. The king of modern baseball cards, period.”

But the ’52 Mantle is much more, too. It is a slice of Americana, recognizable enough to have cameoed, for example, in a ’92 episode of Family Matters, where Urkel trades his card for a favor from R&B singer Johnny Gill. For one generation, it evokes a time when baseball cards were flipped, crimped and stuck in bicycle spokes. For another, it’s a bellwether stock, whose value has never been higher.

Perhaps, though, the ’52 Mantle is best viewed as the Forrest Gump of trading cards, popping up to witness—or often shape—critical moments in the history of the industry, and of baseball itself. It was born at the dawn of the defining post–World War II card era, as chewing gum companies pivoted to leveraging the power of sports heroes. It was held aloft, lit on fire and dropped into a barrel, for attention, alongside tens of thousands of lesser-valued cards, by a frustrated fan protesting the ’81 MLB players’ strike. It has inspired market-shifting transactions and impacted at least one federal investigation.

Its story is the story of sports cards, and it starts not with a man on a bus bench but on a barge.

Gloria Berger turns 98 later this year, but she remains sharp, living with a longtime housemate—“not a caretaker,” she clarifies—on Long Island, near the cozy Hempstead two-bedroom where her late husband, Sy, mapped out the modern baseball card some seven decades ago. “He would sit at the kitchen table until 2 a.m., writing out the backs of the cards and researching everything three times to make sure he had the right facts,” Gloria says. “He was very excited, but he also took it very seriously.”

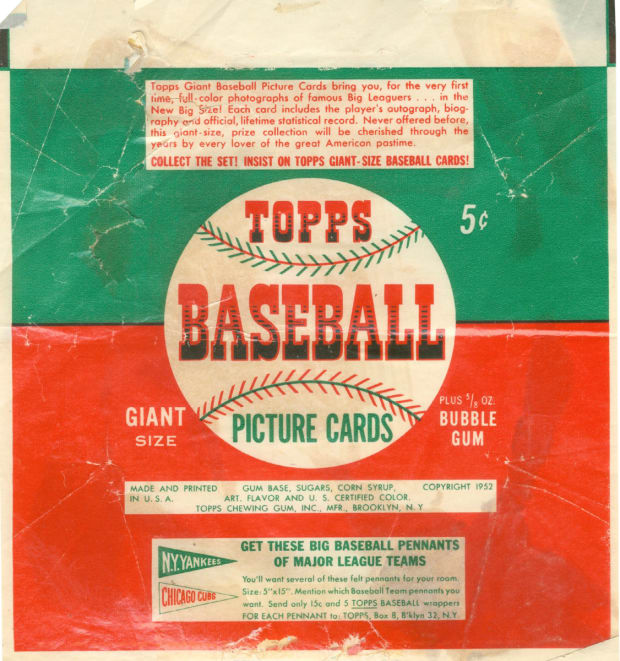

A World War II Air Force veteran, Berger joined Topps as a summer intern in 1947, linking up with an old fraternity brother whose family owned the cigarette-turned-chewing-gum company. In ’51, with Berger in charge of the new project, Topps printed its first baseball card series, a limited release that was packaged with tongue-torturing taffy. “A disaster,” Berger would later say. But he wouldn’t whiff twice. Not only was the full ’52 Topps set (407 cards, issued across six series during the MLB season) bigger than anything that the industry leader, Bowman, had yet produced, but it also debuted full-color photos, facsimile autographs and the backside statistics and bios over which Berger had dutifully pored—all fixtures on sports cards ever since.

Berger was a natural pitchman, frequenting major and minor league ballparks to befriend players of all abilities and lock up their exclusive trading card rights in exchange for gifts—toasters, blenders—from Topps’s home goods catalog. (Their contract signatures were then reproduced for the cards.) And he developed an especially close relationship with the era’s biggest star. “My earliest memory of being in a clubhouse,” says Sy and Gloria’s son Glenn, “is me sitting in Mantle’s lap, watching him wrap his knees.”

Today, the enduring prestige of Topps’s first set—and by extension its signature card, No. 311, batting leadoff in the sixth series—derives in part from the modest, if forbearing, work of its creator. (SY BERGER, WHO TURNED BASEBALL HEROES INTO BRILLIANT RECTANGLES, DIES AT 91, read the headline of his 2014 obituary in The New York Times, a framed copy of which hangs on a wall at Gloria’s house.) But Berger also played a key role in sculpting the set’s outsized popularity long after it rolled off printing presses. Says Gloria, “The only other card history I know is about him dumping them in the ocean.”

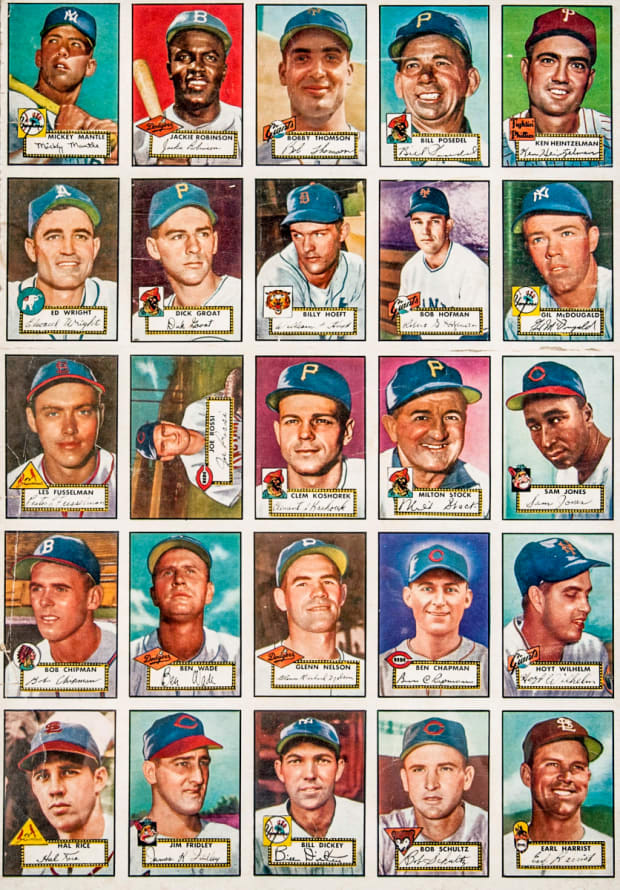

The tale is trading card lore: Stuck with a backlog of unsold cases of the ’52 sixth series at Topps’s Brooklyn factory around ’60, and having struck out in his attempts sell them at steep discount, Berger hauled hundreds of the boxes onto a garbage scow, set sail and drowned all those Mantles, Jackie Robinsons (No. 312) and Bobby Thomsons (No. 313) in the Hudson River, drastically increasing their scarcity.

Is it true? Perhaps. Skeptics posit that, if anything, a smaller count of ’52s was trashed in a broader cleaning effort when Topps moved its production operation to Duryea, Pa., in the mid-’60s. They will also note that Berger didn’t really talk about the barge in public until around the time that Mantle was inducted into the Hall of Fame, in ’74. “I think they created a narrative to some degree, to generate interest,” says Dave Hornish, a vintage card historian and blogger. Whatever the truth, though, the tale’s impact on the market for ’52 Mantles is undeniable. “That really helped cement their mystique,” Hornish says.

Sure enough, when the card industry showed flickers of its first boom, in the latter half of the 1970s, it was the ’52 Mantle acting as catalyst. Classified ads seeking the card, regardless of condition, started to appear in newspapers. One from the Chicago Tribune requested “old baseball cards & 1952 Topps Mantle,” as if No. 311 occupied a stratosphere all by itself. Hobby newsletters, meanwhile, reported bigger and bigger sales, such as a “less than excellent” Mantle raking in $200 at a St. Louis auction, and an “excellent-mint” version fetching $500 from a Maryland collector.

“There is no card more controversial,” Lew Lipset wrote in the June 1978 edition of The Trader Speaks. “Its price rise over the last year has brought forth many advocates and detractors.”

Another high-water mark was reached in March 1980, when more than 12,000 dealers and collectors converged on the George Washington Motor Lodge in Willow Grove, Pa., the highwayside host of what was then the East Coast’s top card show. It was a memorable weekend, marked by Friday’s dealers-only “ballpark supper” (hot dogs) and Sunday’s appearance of two Phillie Phanatic mascots, who made the best of an errant double-booking by chasing each other around the showroom, playfully knocking over tables. But the biggest stir was caused by Saturday’s three auctions.

“We had a [’52] Mantle for each one,” says Ted Taylor, the show’s director, who oversaw a trio of then-staggering winning bids—nearly $10,000 total, he recalls—while wielding his father’s Masonic gavel. After the first one sold, “the room lit up: Wow, did you see what that Mantle went for? . . . Nobody dreamed it would have that kind of value. It just took off like a rocket.”

Life is like a box of baseball cards. You never know what you’re gonna get. For John Broggi, this moment of revelation came at a Baltimore-area Holiday Inn during the summer of 1980. “I was walking around a show,” recalls Broggi, now the executive director of the National Sports Collectors Convention (NSCC), “and I see this guy come in. Under his arm are various-sized sheets of ’52 Topps cards.” Hustling over, Broggi whisked the man away to meet the show’s directors. “I knew he’d be besieged by any dealer.”

The seller explained that his father had worked at a company contracted by Topps to print cards, and that eventually he was bequeathed those fresh-off-the-presses sheets, including a full uncut run of the sixth series, ranging from Mantle to Eddie Mathews (No. 407). “So he unfolds the high-number sheet,” Broggi says. “It was in O.K. shape. Obvious creases. But there’s a Mantle at the top . . . and a Mantle at the bottom.”

Thus was revealed a great contradiction of this holy grail: Despite the ’52 Mantle’s being held up as a rare commodity, it isn’t really all that rare, having been double-printed from the outset—along with Robinson and Thomson—to fill out Topps’s 10 × 10, 100-card sheets. (The double-print Mantle carries subtle differences in color and focus when compared with its doppelgänger. Notably, the stitching on a small baseball on the back points left, not right.)

“Unlike most of the other marquee cards, the [value of the] ’52 Mantle is not based on any actual scarcity,” says broadcaster Keith Olbermann, a longtime collector. “There are literally fewer than 100 Honus Wagners. There is no shortage of ’52 Mantles.” (He owns three of them, all ungraded and one autographed.)

Like the barge tale so famously spun by the father of the modern baseball card, the mother of all Mantle discoveries is universally known among collectors. In the spring of 1986, Al Rosen, a brash New Jersey dealer who’d picked up the nickname Mr. Mint, received a call about a man outside Boston who was said to be sitting on a modest trove of ’52 high-numbers. Racing up the interstate with a briefcase of cash—and flanked by an off-duty police officer—Rosen was elated at trip’s end to find some 75 mint Mantles in the possession of a man whose late father used to fill vending machines and long ago stashed an unopened box in his attic. The sale would require a second trip, as Rosen hadn’t brought along enough money, but eventually he bought the whole collection for what he later pegged at upward of $100,000.

The legendary “Rosen Find” would come to define Mr. Mint’s career, leading to an eight-page profile in Sports Illustrated. At the time, though, Rosen fretted over the potential downside of introducing so many Mantles into the market. “He gave me a call on the way back from Massachusetts,” recalls Broggi, “and said, ‘I’m scared to death I’m going to ruin the hobby.’ ”

The opposite happened. As one columnist wrote in the summer of 1986, detailing yet another Mantle spike, “If you had five of those 1952 Mickey Mantles with the corners and color still sharp, with no stains and no scratches, you could send your child to an Ivy League college for one year. . . . Or buy a new rotary-engine Japanese sports car.” Two years later, after the rest of the economy was crushed by the Black Monday stock market crash—and right at the start of a “junk wax” era of overproduction that would later tank the larger card market—UPI reported that the average value of a ’52 Mantle had nearly doubled over the previous year, from $3,100 to $6,000, and “helped produce the biggest price increases in the history of the hobby.”

Rosen died in 2017, having long since parted with all 75 of those Mantles. But the effects of his find are still felt at the industry’s most lucrative levels. Exact totals are hard to trace, but it’s generally accepted that the vast majority of the 35 PSA 8s, six PSA 9s and three gem-mint PSA 10s in circulation today came from the Rosen Find.

This speaks to a running theme in the legacy of the ’52 Mantle: No matter how many of the cards pop up in dusty attics, fans will never stop paying top dollar for them. Why? Mythology is part of it. But ultimately, as Broggi says, “The power of this card is the power of Mickey Mantle.”

An actor, a broadcaster and a retired ballplayer walk into a bar. The bar is on the ground floor of the Regency Hotel in New York City, where the player is staying on a visit in the early ’90s. The actor and the broadcaster are his good friends, but they’re also big fans, and as the evening wears on, they relive the highlights of the player’s storied career. At last, the player, fed up with all the fawning, interjects in his Oklahoma twang.

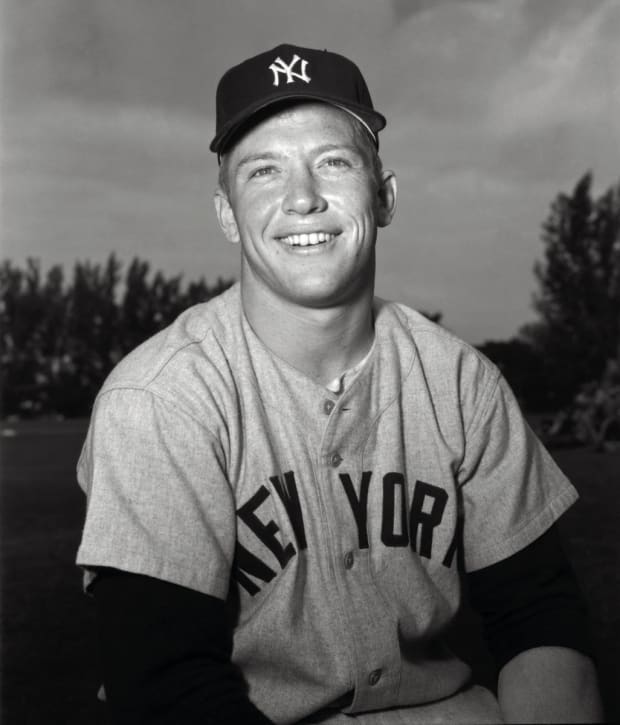

“Day-uuum, I did all this stuff and I can’t remember half of it,” Bob Costas recalls Mantle telling him and Billy Crystal. “But you two little s---- remember all of it.”

Costas, who delivered the eulogy at Mantle’s 1995 funeral, shares this story while explaining how the ballplayer felt about the sky-high popularity of his cards. “He was aware of it,” says Costas, now 69. “But it was only toward the end of his life that he came to terms with it. I think Billy and I helped him get it, because we gave a face and a name to millions of people.”

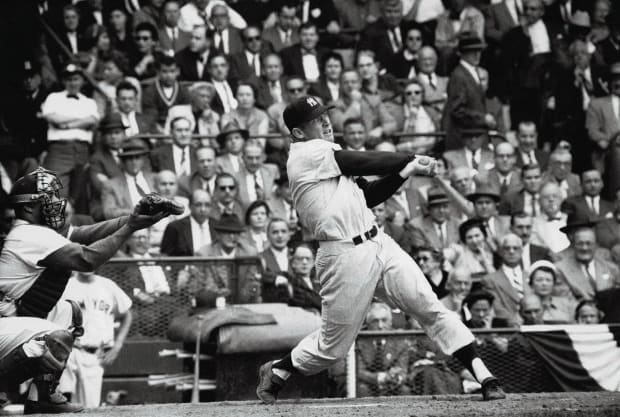

As a player, Mantle was nicknamed the Commerce Comet, after his hometown. With time, though, the moniker took on double meaning, for few athletes have matched his allure on the memorabilia market. “Mantle was like a god,” says John Branca, the nephew of former Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca and an avid collector who previously owned two of the ’52 PSA 9s. “He was larger than life.”

For Costas, the popularity of Mantle memorabilia is tied, in part, to what he calls the center fielder’s “star-crossed” career and life: “At his best, he was one of the three greatest players of his generation, along with [Willie] Mays and [Hank] Aaron, but he couldn’t sustain it as long as they could.” Costas himself is a known collector of Mantle’s cards, to the point that TV viewers have on occasion sent them as birthday gifts. Over the years, he has assembled every single Topps issue except one: ’52.

“It’s a little pricey,” he says of that year’s Mantle, which he insists he’s never tried to acquire. “My connection to it is all nostalgic. I never thought of it as an investment.”

Tom Candiotti Did. He caught the collecting bug in 1986, in the third summer of his 16-year MLB career. One morning, on the road in Texas to face the Rangers, the knuckleballer, then with Cleveland, took a detour en route to the ballpark, following a crowd into a convention center that was hosting the seventh NSCC. “My jaw dropped, looking at all those booths and cards,” he says. “I spent maybe three hours in there. Met a couple dealers. And, little by little, I started accumulating some stuff.”

Before long he was poring over price guides, searching out collectors on road trips. In 1998 he bought an ultra-rare T206 Eddie Plank for $200,000 and brought it to the A’s clubhouse to show his then teammates. “[Jason] Giambi looked at it and crapped his pants,” he says. The next year, back with Cleveland, Candiotti placed the winning bid of $104,000 on one of the three PSA 10 ’52 Mantles. “I likened it to real estate: Get the best house in the best location, you’ll never go wrong,” says Candiotti, 63. “If you get the best card in the best grade, probably not going to go wrong.”

In the end Candiotti, now a radio analyst for the Diamondbacks, sold his PSA 10 to Arizona owner Ken Kendrick, a megacollector who lent the card to Cooperstown for temporary display but has no plans to ever part with it. (Kendrick, whose net worth is estimated at $600 million, declines to say how much he paid.) Ditto for Denver lawyer Marshall Fogel, whose own PSA 10 descended from the Rosen Find, worked its way to a Connecticut card shop and moved through the hands of several industry power players, including PSA founder David Hall, before Fogel made it the first six-figure Mantle purchase, for $121,000, in ’96. “My joke is that I’m gonna lay the Mantle card right on my coffin,” he says. “Or clutched in my hands.”

Which is why the wallets come out whenever high-quality Mantles come up for sale. Retired NFL lineman and Super Bowl 50 champion Evan Mathis can attest to that. He recalls once selling a PSA 8 to a collector who forked over $230,000, all in $20 bills, which Mathis says he “immediately” blew shooting dice with teammates. Soon after, he “got super aggressive” and bought a PSA 9 for $2.9 million, leading him to ask the Cardinals, his team at the time, to convert some salary into a signing bonus, so he could finish paying for the card. (Mathis later sold it for roughly the same price, seeking to divest his portfolio; that same Mantle was the record-setter bought by Gough.)

Vintage card enthusiasts get giddy speculating about how many millions one of the PSA 10s could net today. “If one came up and hit 50, I wouldn’t be surprised,” says Duncansville, Pa., dealer Dave Zuba. Jason Koonce, who runs a store near Ann Arbor, Mich., goes even higher: “In my mind, a Mantle 10 is gonna be a $100 million card one day. People are already paying $70 million for digital art. We’re headed in that direction.”

The third PSA 10, after Kendricks’s and Fogel’s, belongs to a private collector who has succeeded in staying anonymous, though one broker in Denver says he recently brought that owner a $20 million offer, on behalf of an investment group, which was declined.

And when you get to those kinds of numbers, says Brian Brusokas, a member of the FBI’s art crime team, “unscrupulous players will enter the market.” He has evidence. Among the goodies Brusokas uncovered during an investigation into Little Rock collector John Rogers, who in December 2017 was sentenced to 12 years for a $23 million memorabilia fraud scheme, were five counterfeit ’52 Mantles, which Rogers had printed out and handed to banks and investors as collateral for lucrative loans.

The particular ’52 Mantle that would go on to shake the entire trading card industry first enjoyed a humble existence: It was opened in a pack during the year of its release, at a corner store in North Sydney, Nova Scotia, entering the care of a 10-year-old collector who’d saved up five cents shining shoes for neighbors. Its owner grew up to become a public school teacher, always drawing a crowd of students when he brought it to class, but mostly it remained tucked away behind the fridge, inside a plastic grocery bag.

When that teacher died, in January 2018, at 75, his family decided to sell his collection, including the Mantle. Buyers were invited to his kitchen, where cards had been stacked on a paper towel, next to a pair of rubber dishwashing gloves, for handling. Among those who ultimately made an offer on the Mantle ($25,000 Canadian—then about $19,000 U.S.) were Shane and Trevor Russell, who remembered it from when they’d attended the teacher’s school.

The brothers recall ogling the card that day. “The colors just popped,” Shane says. “It was almost mesmerizing,” Trevor adds. But the card wasn’t without its flaws—rough edges and corner wear—and those details, captured in close-up photos snapped in the teacher’s kitchen, stuck with them even after they were outbid.

Haunted by the Mantle and the missed opportunity, the brothers kept a watch on the market, and it was Trevor who perked up later that year when a PSA 4.5 Mantle sold for nearly $46,000, through Heritage Auctions. “Just from the vivid hue, this bit of a tilt that it [had], I was positive it was the [same] card,” he says. The same but different. In its display case he noticed now that the edges were smoother, the corners less worn. “Something didn’t sit right,” he says.

In April 2019, the card was again put up for sale, this time through the online auction house PWCC but encased in a different holder, with a new serial number, suggesting that someone had resubmitted it to PSA, hoping for a higher score. Trevor logged onto the collectors forum Blowout Cards under the username astrotrevor and started a thread titled “52 Mantle PWCC Auction.” He attached three sets of pictures: from the teacher’s home, on the paper towel; and from the Heritage and PWCC sales.

Scrutinizing the Mantle’s unique fibers and marks—the equivalent of fingerprints, attributable to the far-from-flawless manufacturing technology of the 1950s—fellow users agreed that all three cards were the same. And from there, Trevor says, “it blew up.”

The thread filled with allegations of card-altering—broadly, the unsavory practice of trimming, pressing, soaking, sanding, smoothing, recoloring or otherwise artificially changing a product—and not just about the PSA 4.5 Mantle but also about piles of other cards. Eventually the thread was renamed “PWCC Altered Cards Callout,” which at last count had reached 7,500 messages. (Among those accused of trimming, in a separate thread, was Mathis, who in a lengthy email to SI wrote, “To the purists who think a card should always be in its original condition: That just isn’t going to happen in the current state of the industry, and you should avoid buying graded cards.”) More cases, dug up by hawk-eyed card sleuths, surfaced across the collecting corners of the internet, implicating dealers and brokers and graders alike, and later that summer The Washington Post reported that the FBI was investigating both PWCC and PSA.

The scandal sparked wider debate, too, about the role played by PSA and other third-party grading companies in helping shape market movement. Graders, says Olbermann, “destroyed the hobby, generally don’t know what the f--- they’re doing and aren’t uniformly honest.”

Trevor Russell, despite all this, hasn’t ruled out one day taking another run at the old math teacher’s Mantle. “I’d consider it,” he says. “But I’d keep it, pass it down. Not as something I’d be looking to sell, but more of a conversation starter that helped bring attention to something in the hobby that was overlooked for years.”

Von Miller was buying a Ferrari. At least that was the plan. Then the Broncos’ edge rusher spoke in January to a buddy who’d recently spent a truckload on a different kind of flashy purchase and advised Miller to rethink his allocation. “Hey man,” Rob Gough told him, “you should get into baseball cards.”

In the end, Miller redirected his Ferrari money to Gough, who built him a high roller’s starter pack, headlined by a 1986–87 Fleer Michael Jordan rookie and a PSA 6 ’52 Mantle, adding up to about $500,000 worth of cards. “He hooked me up,” Miller says. But it wasn’t until a recent afternoon that he even bothered to look at his new collection. (He was out of town when the cards arrived; a personal assistant stuck them in a safe at his Denver home.)

As Miller fishes the cards out and palms the Mantle for the first time, excitement seeps through the phone. “You can just feel the prestige,” he says. “Mickey looking to his right, bat on his shoulder. It’s just so vintage.”

Miller is far from the only one buying into the hype. Flush with disposable income and brimming with pandemic-born free time, investors have lately flooded all corners of the sports memorabilia market, leading to unprecedented price increases. The supply is ample, too. In April, citing a “growing surplus” of submissions, PSA took the drastic step of temporarily suspending its grading services.

In an era of collecting defined by nonfungible tokens and the livestreamed opening of packs (or “breaks,” per the parlance), the ’52 Mantle is pulpy proof that vintage cards aren’t going anywhere. On the equity-share trading platform Rally, a share of a near-mint version—mere fractional ownership, essentially, of a dismantled Mantle—is currently valued at $228 (based on 1,000 shares). “You used to be able to get a ’52 Mantle for $1,000, and now you can’t even get a corner of one for that much,” says Al Crisafulli, of New Jersey’s Love of the Game Auctions. “The high stuff is on the moon right now.” (Further proof: A 1914 pre-rookie Babe Ruth card reportedly broke Gough's record of $5.2 million in a recent private sale and is currently valued at $6 million.)

Which is why, whenever Robert Edward Auctions president Brian Dwyer gets a call about a longtime collector looking to sell, he always begins by asking whether the client has any Mantles. “There is no condition,” he says, “in which somebody would not jump to buy a ’52 Mantle.”

Yes, those eye-popping sales draw headlines. But just as reflective of the card’s timeless popularity are the Mantles with their eyes poked out. Or with glasses and mustaches inked across their faces. Or staple holes punched in their corners. “That’s just as much fun as owning one that’s pristine,” says vintage dealer Levi Bleam, of Philadelphia’s 707 Sports, whose collection of bad Mantles includes one that was long ago trimmed so that it resembles a cardboard bust. “That’s how kids collected stuff back in the ’50s. They’d play with them. It was a toy.”

Less so now. Of the four ’52 Mantles that sold at Heritage’s spring sports catalog auction in May, two were PSA 1s (the lowest rating aside from “authentic,” which confirms merely that the card was made in ’52), and yet they reaped a combined $57,600. With all these moving Mantles, though, come mixed feelings. Plenty of sellers eventually lament parting with their treasured cardboard. “Obviously,” says Branca, who in the past decade sold a PSA 9 for about $1 million, “we all kick ourselves.”

Count Chris Columbus among those Mantle mourners. The director of Home Alone and two Harry Potter movies started collecting as a late-night diversion from his film work, and in 1997 he paid $16,000 on eBay for a near-mint ’52 Mantle that he kept in a desk drawer, so he could bask in its brilliance whenever he pleased. Seven years later he sold it for $20,000 cash at a convention, for little other reason than his then 12-year-old son thought the high-stakes exchange was the coolest thing in the world.

“I’ve regretted that moment more than any other in my collecting life,” says Columbus, who channeled his grief into the outline of a screenplay that he called ’52 Topps, about three boys who find an unopened box of high numbers at a general store. “It’s probably worth a few million these days, and it’s not like it’s declining anytime soon.”

In his own way, though, he’s not missing out. He held on to several prop copies of the ’52 Mantle that he ordered made for the 2018 movie The Christmas Chronicles, in which Kurt Russell–as-Santa, bereft of his sleigh, tries to swap for a man’s Porsche by conjuring up a mint version. Columbus remembers the collective gasp at one test screening when the man’s wife tears up the iconic card.

Today he keeps the replicas in a bedroom drawer, and every so often he’ll take one out, as before, to admire the full-color photo—the bright-yellow bat, the crisp aqua sky—which he compares in its “absolutely stunning” beauty to a vintage Italian film poster.

Yes, it’s a far cry from mint. But it’s still the Mick.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

• Pete Sampras Is Doing Just Fine