Any other year, Columbus would be hopping this weekend. In 2020, restaurants and businesses will just try to stay afloat.

In such a bizarre season, it’s only fitting that the center of college football in 2020 is found in America’s heartland. And so Sports Illustrated’s two college football writers set out on a (masked and socially distanced) journey to the six campuses in this Midwestern footprint. Ross Dellenger has the northern tier, trekking West to East from Evanston to South Bend to Columbus. Pat Forde is taking the southern route and going East to West, from Huntington to Cincinnati to Bloomington.

We’re rolling out two stories a day, starting Wednesday and running through Friday, as well as updates on our social media platforms, using the hashtag #MidwesternRevivalTour. Keep up to date with the entire series here.

MORE: MARSHALL | NORTHWESTERN | CINCINNATI | NOTRE DAME | INDIANA

***

Ohio State

WHY WE'RE HERE: The Buckeyes are 3–0 and ranked No. 3 in the nation.

SEASON HIGH POINT: Something Justin Fields did, maybe? Ohio State has handily beaten Penn State, Rutgers and Nebraska—not exactly world-beaters this season.

PROGRAM ARC: OSU hasn’t won fewer than 11 games in eight years and has finished in the top five 13 times since 2002—one of the greatest 20-year runs in the sport’s history.

PROGRAM EDGE: What’s not an edge? The Buckeyes have the resources, the recruiting ground and the historic success to match any other team in the nation.

ACADEMIC BRAGGING POINT: OSU routinely ranks in the top 20 as one of the best universities for “college value.” It ranked first among U.S. flagship universities for efforts to control in-state tuition over the past decade, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education.

CAMPUS ICONOGRAPHY: The Horseshoe, of course.

PLACE YOU MUST VISIT: Buckeye Donuts is an institution that you should frequent.

***

COLUMBUS, Ohio — There's a false positive at Mike's.

It’s not what you think.

Mike isn’t a person. Mike’s is a bar. And this false positive has nothing to do with the surging COVID-19 pandemic. It’s a cocktail of booze—Strawberry Lemonade Svedka vodka plus Faygo Red Pop—swirled into a mixer and poured into a shot glass.

The High Street bar near downtown Columbus also serves up a contact tracer: Vanilla Svedka combined with Faygo Orange Pop.

By 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, a half an hour after Mike’s opened, five people are belly-up at the bar, either sipping beer or shooting COVID-themed shots. Or sipping beer while also shooting COVID-themed shots.

It was a snapshot of a pre-pandemic time, a somewhat unsettling but also, maybe, understandable display from a group with serious COVID fatigue.

Can we just get back to normalcy already?

Hardly. This region of the country is experiencing such soaring virus cases that the disease lurches like a dark cloud over a city that’s supposed to be buzzing with football fandom ahead of Ohio State's game against Indiana on Saturday. Two undefeated, top-10 Big Ten squads are meeting at the Horseshoe. This place should be bonkers.

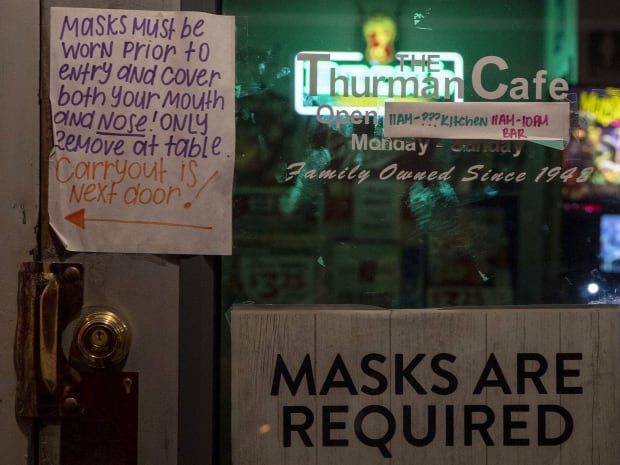

Instead, it is being shuttered. Coincidentally coinciding with Saturday’s game, the state’s Republican governor has imposed a curfew of 10 p.m. and the city’s mayor has instituted a 28-day stay-at-home advisory, each effective beginning this weekend. In fact, amid rising cases on Thursday, Franklin County—home to Columbus and the university—became the first in Ohio to be upgraded to the state's highest advisory on its COVID map: A Level 4 Purple. Under a purple advisory, the state advises residents to only leave the house for necessary/essential reasons.

“It f------ sucks bad,” says Kim Hannen, speaking from within Mike’s, herself a bartender across the street at Mac’s Proper Pub, both places among several hard-hit spots in an entertainment district that’s a five-minute drive from Ohio Stadium, the Buckeyes’ goliath football venue.

Like much of the nation, Ohio seems torn over COVID restrictions, somewhat split politically, the state’s urban centers surrounded by rural stretches.

A battle rages here between the governor and the leaders of this city’s restaurant and bar industry, most of them already in serious financial crisis. In fact, Gov. Mike DeWine’s curfew was somewhat of a compromise. State officials decided against a complete shutdown of bars and restaurants.

Things are going from bad to worse. As the state and region continues to set ugly pandemic records, the wintry weather is depriving eateries, already hampered by indoor limitations, of outdoor dining. New restrictions will further cripple revenue and will prevent anyone from attending Saturday’s game (Ohio State had previously allowed player families to attend).

“We’re just trying to stay afloat. There’s no making money right now,” says Scott Ellsworth, the owner of two Columbus bars called Threes and Fours.

Game-day revenue is down roughly 70%, and he’s needed to acquire a loan to keep one of his bars open. Ellsworth is sympathetic toward the pandemic and understands the concern over the rising cases, but as the father of an 11- and 14-year-old, his livelihood is at stake.

“The governor has a wild hair up his ass about bars and restaurants,” he says. “You’re hoping to make enough money to pay staff and rent and keep the lights on.”

So many here can’t. According to surveys conducted by the Ohio Restaurant Association, 58% of restaurants in the state operating at their current capacity (tables must be six feet apart) will close within the next one to nine months.

The city of Columbus has more than 4,000 food establishments employing more than 80,000 people, or roughly 15% of state-wide numbers. Imagine that roughly sliced in half, says Homa Moheimani, manager of media and communications for the Ohio Restaurant Association.

“These are real people, real stories, peoples’ livelihoods,” Moheimani says. “This is the heartbeat of America, of our state and country. They’re doing everything they can.”

The absence of fan-attended Ohio State football games trickles through this place’s economy, says Mike Stevens, the city’s director of development. For example, Columbus uses a bed tax revenue to fund a large portion of its human services department, which among other things cares for the city’s homeless population.

The bed tax is drastically down, he says. According to Linda Logan, the executive director of the Columbus Sports Commission, 25% of Ohio State football game-goers stay at least one night in a hotel. That accounts for at least 10,000 rooms.

Ohio State hasn’t conducted a recent economic study, but Logan gives a low estimate herself of game day impact in the city. Imagine if $100 was spent by each person who attended an Ohio State home game, she says. The stadium seats 104,944. That would equate to more than $10 million.

The hospitality industry isn’t the only one feeling an impact here. Kelly Dawes owns College Traditions, a 36-year-old Ohio State apparel shop along the border of campus and just a couple hundred yards from Ohio Stadium. On this Thursday afternoon, she’s pecking on a keyboard from her office while her store sits fully stocked, which isn’t a good thing.

She estimates that half of her annual revenue is generated from the seven home game weekends. Those weekends are producing about 10% of their normal rate.

She must order apparel a year ahead of time. The sea of scarlet and gray before her was ordered last November, five months before the pandemic hit the U.S. She finds herself in quite the pickle. She has an abundance of merchandise and now, on that computer, is having to order next year’s batch.

“I don’t know how much to order. I’m trying to forecast,” she says before asking a question that every American is wondering: “It can’t still be going on, right?”

Back at Mike’s, bartender Sharon Lyons estimates that she’s making about 25% of normal revenue, on the high side of most places. Why? Mike’s is a local dive with a reliable inventory of regular customers.

Lyons describes MIke’s as an “early bar.” The pandemic-adjusted hours have it opening at 10 a.m., but it normally opens at 6 a.m., with regulars streaming in for their liquid breakfast (Mike’s doesn’t serve food).

Lyons only began pouring drinks at Mike’s in January. Despite the pandemic and attendance restrictions, she had high expectations for the Buckeyes’ first home game of the season against Nebraska.

“I thought I was going to make bank,” she says. “I had three people in here for the entire game.”

So, on Saturday, while two undefeated teams clash in the Horseshoe in one of college football’s biggest games, all around it a virus-stricken city aches.

“The hope,” Ellsworth says, “is you take your beatings for a year and next year you come back, hopefully stronger.”

MORE: MARSHALL | NORTHWESTERN | CINCINNATI | NOTRE DAME | INDIANA