MLB has never been in a more weakened position to withstand a work stoppage than it is now.

JUPITER, Fla. — A light breeze tickled palm trees. The late afternoon light of what the photographers call “golden hour” invited daydreams. A pristine field where the Mets were scheduled to play the Marlins lay empty. A tableau that should have been idyllic instead smacked of poignancy and loss.

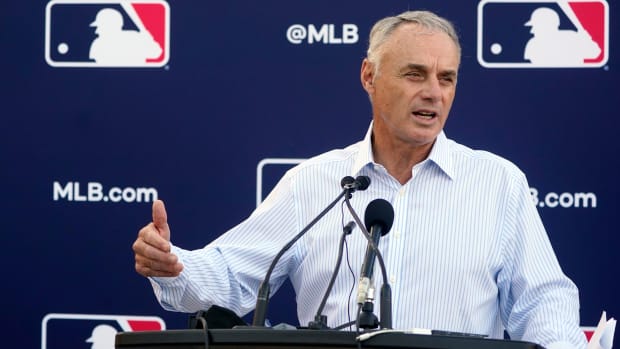

Off the left-field corner of the Marlins’ ballpark here, in a concourse that should have been full of sun-burned fans and families leaving with smiles and memories of a day at the ballpark, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred announced the cancellation of the first week of games of the now forever-tainted 2022 season. And with that, on what was exactly the kind of day baseball should own, the sport hurtled itself deeper into danger.

Wilfredo Lee/AP

If you think this work stoppage might be a short one, you were not paying attention to the gaps between the owners and players Tuesday, throughout nine days of negotiations, and really since the ink dried after the past Collective Bargaining Agreement was signed in 2016.

There is no baseball today because of a labor dispute in a business that generates $11 billion in revenue. In truth, this day was five years in the making, ever since the players whiffed on the last Collective Bargaining Agreement while focusing on comforts over economics. Their mistake compounded when data-smart front offices McKinsey-fied baseball with a brutal efficiency that squeezed every dollar and spawned a risk-averse game that is played slower than ever before.

COVID in 2020 accelerated a disconnect between players and owners. Amid a worldwide pandemic, they distastefully fought over when to play their little game, establishing a three-year streak in which they could agree on nothing. Resentment piled up.

The 60-game season also retrained baseball brains. The sanctity of the 162-game season was diminished. The pay and the postseason from even a truncated season were rewarding enough that the loss of games was no longer such a scary thought on both sides.

In the mockingly beautiful end, an air of inevitability hung over Jupiter. Players and owners saw their exceedingly rich kingdom with different perspectives. Players saw a sport with revenues increasing and pay scaling back to its lowest level since 2015 and fought for disruption. Owners leaned on one their favored saws, competitive balance, and fought for keeping status quo as much as they could.

APSTEIN: MLB Owners Fail to Realize Their Own Foolishness

It was bound to come to this, especially as evidenced in the death of the last breath of hope. Owners tried deep into the night of Monday to close out a deal, while players asked for time the next morning to canvass their representatives. The Zoom call Tuesday morning with player reps took 2 ½ hours, and suddenly the fishing line snapped on what the owners thought was a deal within reach.

“It changed suddenly,” one MLB source said. “It was back to playing whack-a-mole.”

It turned out the two sides never were close, especially on the Competitive Balance Tax. There are many causes that can be listed when they do the autopsy on why a deal died, but the CBT is the primary cause of death. The two sides were not close in math or concept.

Several times Manfred while delivering his eulogy referenced the CBT as the owners “only mechanism” for addressing payroll disparity and competitive balance. It is a tax levied on high-payroll clubs from slowing down their spending. Without it, or with a threshold not high enough, the owners contend, teams such as the Dodgers, Yankees and now the Mets would pull ridiculously ahead of the Rockies, Rays and Marlins of the world. In the past two CBAs, the CBT rose not at all in 2012 and by 3% in 2016. Owners asked for a 5% bump this time, “right in line,” Manfred said, with the recents agreements.

On Tuesday midday, after their Zoom session, players presented a package that asked for a threshold that started at $238 million and topped out at $263 million, slightly down from their range of $245 million to $273 million. The first-year threshold in the new proposal represented a 13% raise.

Owners were flabbergasted. They saw the players’ incremental move as a poke in the eye. The owners came back with a final offer in which their CBT first threshold did not change. It remained at $220 million. That was the moment the season as we knew it was lost.

The owners are “now attempting to use CBT as a salary cap,” one source close to the union said. “Rob agreed not to use the CBT for this purpose in 2002.”

Wilfredo Lee/AP Photo

The shame is that owners did address criteria important to players, such as getting more money to young players, such as the largest increase in minimum salary (up $129,500 to $700,00) and bonus pool for pre-arbitration players (though the gap between the two sides, as in the CBT, was enormous). The owners caved on their 14-team postseason proposal to accept a worse proposal from the players for 12 teams.

But in the end, nothing seemed more out of place than making no movement on the CBT in their final offer. Small-revenue teams felt they were taking it on the chin in the proposed deal (minimums, no draft pick compensation on free agents, a draft lottery, etc.) and they were not going to let Manfred push the CBT any higher.

“When you look at the all important last number,” the union source said, referring to the exit year of the deal, the difference is enormous: $228 million to $263 million. A gap like that makes you wonder how close they could have been to closing a deal late Monday.

That gap also is foreboding. The game has been retreating in the American consciousness because of the product on the field. Baseball keeps giving fans less action over more time, a recipe for irrelevance in today’s multi-screen world. Dead time in a game since Manfred became commissioner in 2015 has increased 17%. It’s not all on him. Players keep saying they don’t want to be told to hurry it up, cluelessly slow-playing their own way into oblivion.

The breakup Tuesday has one very small beacon of light. Manfred will almost certainly implement a pitch clock and ban on defensive shifts in 2023, as is his prerogative. He wanted an agreement with the players on pace of play, but like most everything else could never get to a true partnership. The game will change. It may be too late.

In the meantime, baseball continues to fade. Already they have squandered the charm and beauty of spring training. Gone now is the symbolic importance of Opening Day, which used to be a secular holiday in celebration of not just the sport but the arrival of spring and the shedding of parkas and short days. Soon to come are games after games, series after series, while the toxic fumes of these labor negotiations, such as they are in the coming days and weeks, denigrate the sport.

There have been labor stoppages in baseball before, but not in 27 years and never has the sport been in a more weakened position to withstand it than it is now. This day, beautiful as it should have been, reeked of loss. Profound, ominous loss.

More MLB Coverage:

• MLB Owners Fail to Realize Their Own Foolishness

• This Is the Path MLB Chose

• Derek Jeter Is a Player Again

• Rob Manfred’s Argument About Owning an MLB Team Is False