Maintaining the fallacy that football compares to war misrepresents today’s game and can minimize the commitment of the members of our armed services.

View the original article to see embedded media.

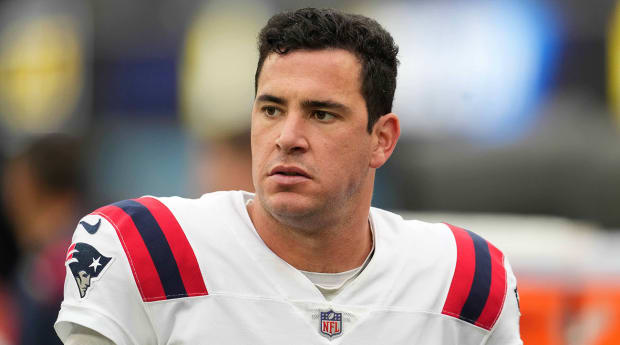

With Albert Breer on vacation, we bring back our annual tradition of having guest writers fill in for his Monday Morning Quarterback column. This column comes from Patriots long snapper Joe Cardona.

As famed 18th-century general Carl von Clausewitz said, “Everything in war is very simple. But the simplest thing is difficult.”

Football is no different, and, at its purest, it fundamentally mimics war. Offensively, one must simply advance through resistance to acquire new territory until you eventually reach the objective. And, defensively, it is your mission to slow the advance and push to take the offensive.

The original game, created in American universities after the Civil War to give young men a forum to experience the trials of combat, was especially brutal. Between 1904 and ’05, The Chicago Tribune attributed 37 deaths to the sport. The sport was so deadly that many universities abolished it altogether. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had a deep appreciation for the principles the game represented, felt the need for executive action to protect the game by making it safer to play. So in ’06 he helped institute rules removing mass formations and introducing the forward pass. These changes ushered in the game played today.

When asked to contribute to The MMQB, I assumed my contribution was expected to focus on football and the military. I am entering my eighth year as the long snapper for the Patriots and am a lieutenant in the Navy. I walk between two mentally and physically demanding careers, an experience I share with legends who came before me, such as Roger Staubach, Chad Hennings and Alejandro Villanueva.

Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports

All three of those individuals were committed to both the profession of football and the profession of arms. In reality, I have struggled with my place between these two careers, mainly taking solace in the fact that there are many traits and characteristics that lend well to both careers: athleticism, teamwork, mental and physical toughness, and a desire to reach a common goal.

But football no longer mimics war or the values held close by our armed services.

Football began with Ivy League athletes running a leather ball downhill. Platoon-system substitutions meant athletes played the entire game without a break and with a focus on physical dominance. This form of football shaped and hardened the young men who eventually fought in places such as Argonne and Belleau Wood in World War I, and Normandy and Guadalcanal in World War II. The toughness and tactics of football simultaneously influenced, inspired and developed combat leaders who defeated Nazis, fascists and imperialists.

In the latter half of the 20th century, increasing revenue through television contracts took football to another level. Higher salaries for players allowed the sport to be a full-time job, and the link between those who played football and those who fought on the front lines for the U.S. began to fade.

In this day in age, individualism has encroached on professional and amateur football, rules of uniform regulations are loosely enforced, and celebrations are embraced for the value they can bring from TikTok views or Instagram likes. Media revenue surrounding football has grown tremendously, leading to both players and teams looking to find a way to monetize social media, fantasy sports, legalized gambling or whatever technology will surely emerge in the future. Analysts, fans, coaches and players alike talk about football, in particular the NFL, getting “soft.”

The cliché that football builds toughness is not as universally believed as it once was. This is based on player attitudes, reduced commitments to one team and increased compensation. However, it can be argued that football’s movement away from comparisons to the battlefield of war is for the best. Football is safer, and it offers young men, a majority of whom are men of color, a platform and the resources to receive an education and build generational wealth that may not have otherwise been available to them.

Today, football is not war; it is money.

Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports

This is not to say that there is a complete lack of selflessness, commitment and toughness within the NFL. Rather, I believe football now exists in a completely different stratosphere than what is required by our active-duty servicepeople. But it isn’t without comparison.

More than 1.5 million veterans live below the federal poverty level, according to the National Veteran Homeless Support. Young veterans, veterans of color and female veterans are the most vulnerable. Ten percent of young veterans are poor. Veterans of color are twice as likely to live in poverty. Additionally, an estimated 160,000 active service members experienced food insecurity in 2020.

The military members putting their lives on the line see pennies on the dollar compared to our major defense contracts in our $773 billion defense budget. It’s much like the NFL, where most players do not see nearly the value of revenue generated at the expense of their physical and cognitive health because it goes to ownership, the league or a handful of players who command a disproportionate allocation of the salary cap.

While the strategy of the game in a stadium and that on the battlefield still share many comparisons, football is not war. Even though football was created to harden young men in America—so they remained ready for potential combat—that is no longer its purpose. The commitment and dedication to country and mission by military members are not factors in today’s football generation, despite growing up during a 20-year conflict. Young college players are often seen entering the transfer portal at the first sign of resistance, and players in the NFL demand trades and refuse to play as a contract negotiation tactic. That does not happen in the United States military. Yet, these young men have every right to; football is not war.

Zooming out for perspective: The ever-shifting international landscape of geopolitics—including a major conflict in Europe as Russia looks to expand its borders and the influence of China’s rising presence in several regions around the world with a growing military and economy—has put the possibility of a major superpower conflict at the forefront of many Americans’ minds. If there were ever such a conflict, just like in previous wars, the NFL would take a back seat, and I have no doubt many of my peers playing football would step up and use the lessons they learned from the sport to lead soldiers into combat.

But that doesn’t make football war.

While some may yearn for the days when football mimicked war—when it emphasized character, integrity and courage, and developed young men who demonstrate selflessness, commitment and toughness—that is not what football is today. Football is big business and has migrated to a place of its own, serving as a major part of American culture and showcasing some of the most physically dominant and talented men in the world.

Yet, these professionals are not on a battlefield. Maintaining the fallacy that football mimics war misrepresents today’s game and can even minimize the commitment and dedication of the members of our armed services. Football’s doing more to emulate the U.S. military could pay dividends for the sport and the audience that consumes it. Imbuing young football players with the ideals of courage, commitment, honor and toughness will serve them much more effectively in life than any route technique, coverage scheme or viral touchdown dance.

Football is not war, and that is O.K., but we must not lose sight of what America truly needs the sport to be.

More NFL Coverage: