The Sheppard sisters became elite runners while living in a homeless shelter.

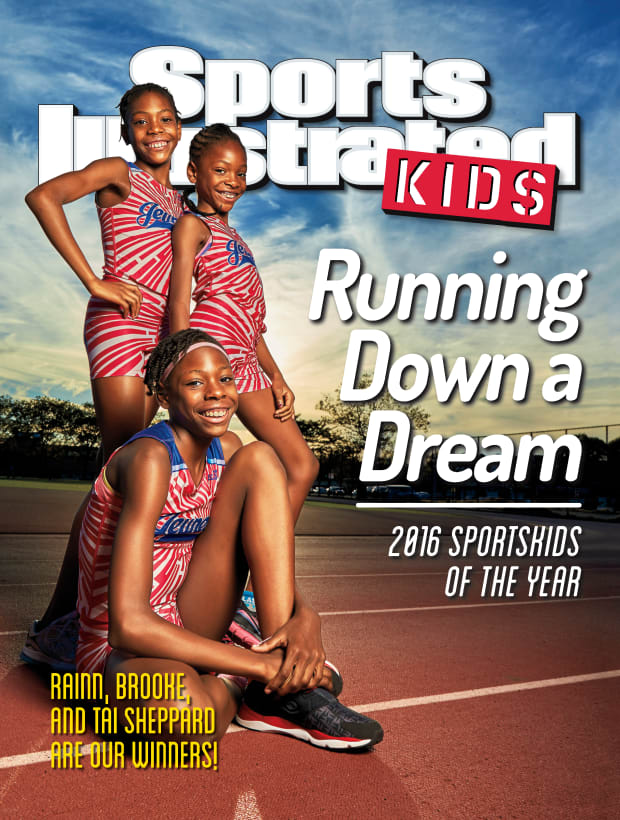

At the beginning of Sisters on Track, which is now streaming on Netflix, Tai, Rainn and Brooke Sheppard are being named SportsKids of the Year for 2016. Theirs was a remarkable story: The sisters, ranging in age from 9 to 11, moved into a Brooklyn homeless shelter with their mother, Tonia Handy, when she could no longer afford their rent. That didn’t stop them from competing in track and field at an elite level. (Full disclosure: As managing editor of Sports Illustrated Kids, I was part of the team responsible for giving them the award, an experience that remains the most rewarding of my career.)

The SI Kids cover was unveiled to the girls and their mom on an episode of The View, where they were given even more amazing news: Tyler Perry was going to set them up in an apartment and pay their rent for two years. It was obviously wonderful and life-altering for the family, but it also changed their narrative.

That’s significant, because just before the girls started blowing up, two documentary filmmakers, Corinne van der Borch and Tone Grøttjord-Glenne, began filming the family. Suddenly the story was no longer the Olympic dreams of three homeless girls. Instead it was something far more broad: the struggles of being a kid (especially a Black one) in the U.S., even one who lives in a nice apartment. While that may sound less dramatic, the finished product is utterly compelling.

The sisters dream big. Tai, the oldest, wants to be an Olympian and also a biochemist. Brooke, the youngest, wants to be an artist and a track runner. They interact about the way one would expect them to: “My sisters are very annoying, as sisters should be, I guess,” Rainn observes before ultimately concluding 20 seconds later: “They’re awesome.”

The usual problems pop up. Pimples. (Tai takes over the crew’s camera to film an impromptu course in popping them.) Boys. Homework. But there are also more serious issues, reminders that even if you take away the biggest problem facing a person, there’s usually plenty of smaller ones ready to crop up. Rainn gets mad at a teacher and throws a crayon at her leg, putting her track season in jeopardy. Tai and Rainn’s quest for high school scholarships hits several bumps. And when it comes time to start high school, Tai is less than enthused. She proclaims that the day before school starts is important because it’s when you get your hair done and “mentally prepare to say goodbye to having fun,” before confessing, “I’m just nervous. ... Maybe I don’t look cool enough. ... I’d like to go back to middle school, mostly because I don’t like change that much. Change is different, and I don’t know how I’ll react to change.”

The doc is not just about being a kid, though—it’s about raising one as well. Tonia, the girls’ mother, is a warmhearted, wise, caring woman who ended up in a homeless shelter for the simple reason that minimum wage does not mean living wage. I first met her in the fall of 2016 and was amazed by her buoyancy and optimism. Her life hasn’t been easy. She’s endured bad relationships and lost a son, the girls’ half-brother, to violence. (“He went to a party. He got shot. I really miss him,” Brooke matter-of-factly tells the camera.) On-screen, Tonia is as indefatigable as ever in her advocacy for her kids. In one of the film’s most moving sequences, Tonia tells the camera that she won’t let herself get into a relationship with a man as long as the girls are still living with her. “When I do fall in love, it takes me over,” she says as tears form in her eyes. “I’ll wait until they’re out of the house, you know, so I can have my moment.”

Just as Tonia’s financial resources are strained, so is her parenting bandwidth. Raising three tweens is hard under the best of circumstances; doing so alone is unimaginably taxing, especially when holding down one job while looking for a better one. That’s where sports come in.

The girls are part of Brooklyn’s Jeuness Track Club, founded and overseen by Jean Bell. Coach Jean’s day job is as an administrative law judge for the New York State Department of Labor; she’s clearly not the type of person to brook nonsense, on the track or off it. The club is girls-only (in fact, outside of a few classmates and one chiropractor, Sisters on Track features female voices almost exclusively), and Jean’s primary reason for running it and pushing the girls is simple. It has nothing to do with a runner’s high or the thrill of competition. “The object of the team,” she tells a group of parents, “is to get them an athletic scholarship so that they can go off to college and you don’t have to put out money.”

Coach Jean’s duties, though, extend well past explaining the finer points of baton passing. She runs a book club at which the girls study The Hate U Give and discuss the differences between being raised Black and white. She gives a birds-and-bees talk, complete with drawings, as the girls alternately die of mortification and ask pointed questions. She doles out hugs but willingly plays the heavy. As Perry’s two-year gift is about to expire, Jean asks Tonia whether she’ll be able to make ends meet. Yes, says Tonia, but it will mean saying no to the girls. “Or you call me and I’ll say no,” says Jean.

Of course, Sisters on Track follows the exploits of the girls on the track as well, but the races themselves feel like they’re of secondary importance. Not ginning up those stakes means the movie doesn’t have a traditional third-act resolution. That’s fine, though, because the girls are nowhere near their third act. We’ve seen where they come from, and it’s inspiring. We don’t know where they’ll end up, but given their spirits, and the support network of remarkable women around them, it’s hard to believe it won’t be a place of greatness.

More News:

• How Michigan Failed to Protect One of its Own From Sexual Assault

• Forde: My Daughter's Long Path to the Olympics

• Student-Athletes Speak Out to Oppose NIL Proposal