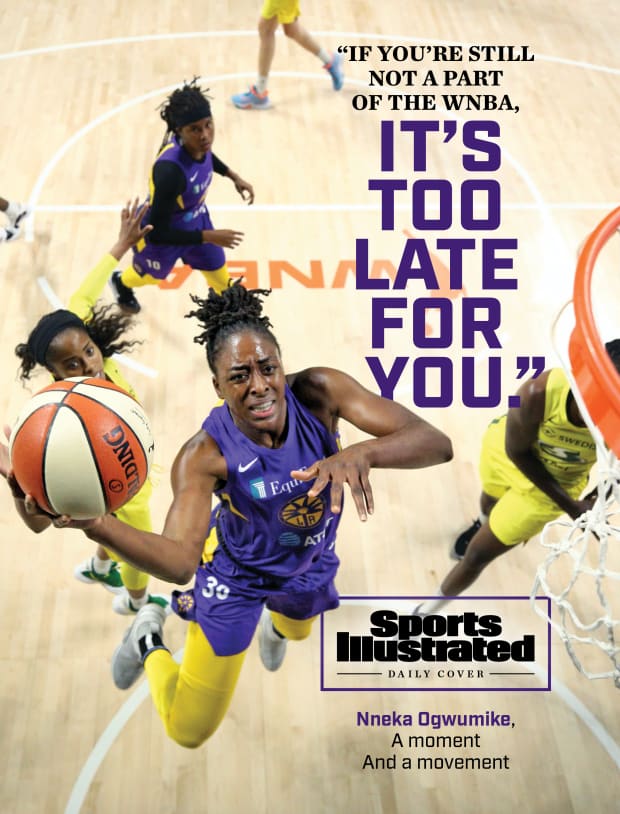

On and off the court, the Los Angeles Sparks forward operates with patience and precision

Those who know Nnemkadi (Nneka) Ogwumike best do not lack for nicknames to call her. Some are merely run-of-the-mill sports fare, such as Nek, Nek Nek, Nnekanator, and Guma, a rare surname riff (pronunciation: Oh-gwoo-MIH-kay). Others are more illustrative, the ones that explain why some friends and family have suggested, not entirely jokingly, that the 30-year-old Los Angeles Sparks forward should “create a lifestyle book” and market her diverse set of skills to the masses.

Take, for instance, Chef Nnek. Breakfast is her speciality, but Chef Nnek is plenty versatile, whipping up personal favorites such as Nigerian jollof rice (her parents were born there), vegan pasta alfredo (her diet is plant-based) and shrimp enchiladas with dairy-free cheese (she’s lactose-intolerant) for hungry teammates during the 2020 WNBA season. Chef Nnek also takes requests, although these have been limited amid the pandemic, as safety protocol prohibits her from leaving the league bubble in Bradenton, Fla., for groceries. “So a lot is dependent on what I have available,” she says. “Most times I say, ‘Hey, I’m cooking this,’ and if they want a plate, they’ll come pick it up.”

There’s also DJ Nnasty, who hits the stage whenever Ogwumike is playing music, and Nek’s Nap Salon—no double N—where her sisters go to get their hair done. Nneka Knows is the brainiac of the bunch, constantly deep-diving research topics of interest—such as, to cite one past obsession, the relative bioavailability of agave and honey. And nearby troublemakers should brace for a virtuous storm, “because if I feel as though there’s injustice in some way, then Hurricane Nneka comes.”

Finally there is the honorific by which the six-time WNBA All-Star, 2016 WNBA champion and 2016 WNBA MVP is perhaps best known among fellow players. Asked to describe Ogwumike, Seattle Storm guard Sue Bird chuckles and replies, “Well, probably ‘President’ first comes to mind.”

From her perch as the highest-ranking member of the executive committee of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association, an office she has occupied since October 2016, President Nneka (or, if you prefer, Madam President) governs by the will of the people. The latest example came Wednesday night, when WNBA players decided to join their NBA counterparts in sitting out games to protest the recent police shooting of a Black man named Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wis. As deliberations had unfolded at the IMG Academy over what to do, there was President Nneka front and center—not so much giving directions as directing traffic in phone calls, group texts and in-person meetings to ensure everyone’s voice was heard.

“What was most important was the solidarity, the unity, the collectiveness of how we've always organized,” Ogwumike later told ESPN’s Holly Rowe, wearing a face mask that said CHANGE HAS NO OFFSEASON and a T-shirt that read STOP KILLING BLACK PEOPLE. “My role in what I do as president is to lay out the options and make sure everyone understands the implications of the decisions we make, especially if we do it together. … I ride for my players.”

No wonder President Nneka enjoys a high approval rating from her constituents. “She has that aura about her,” Bird says. Consider everything that Ogwumike has helped accomplish this year alone: The calendar opened as the WNBPA finalized a groundbreaking, glass-ceiling-cracking collective bargaining agreement, the first of its kind in pro sports with regards to benefits for working parents. Then came talks to build the “Wubble” and stage the 2020 season, which passed its midway point last week. All the while WNBA players have remained front and center in the national fight for social justice, as they have for Ogwumike’s entire tenure as the face of their union.

“Nneka’s reputation as a leader in our PA is solidified,” says Bird, an executive committee vice president. “She’s proven that she can get things done.”

This has always been true for the 6' 2" Ogwumike on the court, where she ranks second in the WNBA in career true shooting percentage (.617) and went 8-for-8 from the field in the Sparks’ season-opening win over Phoenix on July 25. She will never be confused for a flashy player, but her screens are set with strength; her back cuts are made with precision; her hustle and smarts have netted four appearances on the all-defensive first team; and she never seems rushed with the ball in her hands, calmly sizing up opponents before making her move. “She’s a beast,” says Tamika Catchings, her predecessor as players’ union president.

It is the combination of these same relentless traits—plus some recurring cameos from her alter egos—that has made Ogwumike well-suited to lead WNBA players through what she refers to as a pivotal moment in league history, when visibility has never been higher and the future has never looked brighter. “Our movement has found its moment, and we’ve capitalized on that moment,” Ogwumike says. “It's glaring now. It’s impossible to ignore.” And while the legacy of President Nneka is far from written, it’s safe to say that no single player has done more in recent years to shape how professional women’s basketball will look for decades to come. As Bird declares, “I think she will go down as the person who changed the trajectory, changed the direction of the WNBA and the WNBPA.”

***

In September 2018, two months before the WNBPA opted out of its old CBA to begin talks on a new contract, union leadership gathered in a Washington, D.C., conference room to discuss their strategy for the road ahead. Among those present were Team USA players, in town on a World Cup tune-up tour, as well as team reps, WNBPA executive committee members, and then–director of operations Terri Jackson. At one point during the meeting, Jackson paused to ask whether any of the players had questions about some internal financial models that’d forecasted future league revenue. Everyone was quiet.

“Nneka actually stopped the presentation and said, ‘I need you guys to pay attention to this,’ ” recalls Jackson, now executive director. “The presentation was on screens around the room, so she gets up from the table and really walks everybody through the numbers. You could see the players nodding their heads as she broke it down. Maybe they were a little nervous, just reluctant, hesitant to ask. But Nneka was not having that.”

For Jackson, the moment was a stark contrast with her early impressions of Ogwumike. They first met in 2016, when Jackson was new to the WNBPA and Ogwumike was a vice president under Catchings. “All of our meetings were via calls, and she’d be so quiet,” Jackson says. “I’d always get off the phone thinking, ‘Gosh, I don’t know if I heard from Nneka.’ ”

As time passed, though, Jackson came to learn that the silence in fact reflected two key aspects of Ogwumike’s leadership style: First, that she wasn’t the type to talk just to hear her voice. (This humility was later apparent in how long it took her youngest sister to learn that President Nneka had been elected, unopposed, to succeed Catchings: “She did it for a year,” Erica Ogwumike says, “and I had no idea.”) And second, that Ogwumike approached situations in the boardroom with much the same diligence and patience as she did defenses on the basketball court. “Someone who really takes the time to get a lay of the land, to carefully gather her thoughts and impressions,” Jackson says.

Ogwumike graduated from Stanford with a psychology degree in 2012, but she never stopped being a student. The agave-honey debate is one of many examples. During quarantine Nneka Knows spent days down a rabbit hole comparing chemicals in various Korean skin care products. “It was like she was writing a thesis,” Erica says. The subject doesn’t even need to be personally relevant. “She asks me a lot of questions about parenting,” says Ogwumike’s agent, Lindsay Kagawa Colas. “That’s not really on her radar right now, but I think that speaks to her being so genuinely interested about what she’s observing.”

As much as she wants to consume knowledge, Ogwumike is also wired to pass what she discovers onto others. It’s why Chef Nnek, evidently fed up that her sisters kept swiping her freshly baked cinnamon muffins, once left a note banning Olivia and Erica from eating any more until they learned the recipe themselves. “Always trying to teach us,” Erica says. And it’s how President Nneka approached the daunting task of rallying WNBA players for the long grind of labor bargaining.

The process started in late 2017, a year before the players opted out, when Ogwumike charged Jackson and other union staff with creating educational resources for members to read and learn the then CBA. “That was something she said at every meeting,” Jackson says. As a result, the WNBPA pushed out a dozen or so weekly “modules,” easily digestible summaries of different sections, such as free agency or benefits. “From the day she took the job,” Bird says, “Nneka has done a really phenomenal job at making sure players have the information and making sure it’s known that, if you want things to change, you have to take ownership with this. If you want something different, you have to speak out about it.”

During negotiations, Ogwumike wasn’t shy about communicating what she had learned that her rank and file was looking to get. Four days after Engelbert left her CEO position at Deloitte to take over as WNBA commissioner, she sat down at the bargaining table and was greeted by Hurricane Nneka. “I remember Nneka giving an opening statement about the plight of the players, how important it was for us to work together in a joint way,” Engelbert says. “I was struck by her maturity that she came with. In subsequent meetings, every time we started a meeting, Nneka would have a statement that she was very thoughtful about and would read that statement either live or on the phone.”

As talks progressed, Ogwumike never lost sight of her overarching goal. “She was really keen on saying, ‘This isn’t just for us, this is for future generations,’ ” Engelbert says. The finished product reflects this focus. Some CBA upgrades were long overdue, such as salary increases, improved travel accommodations, and more equitable revenue sharing. Others were revolutionary, not only in sports but in society. “The benefits that we have for player moms,” Jackson says. “If you read the old CBA, there’s no section on maternity leave, or what it means to be pregnant. I wonder, how many players did we lose? How many did not come back, because they didn’t see the support? Nneka understood that.”

After the new CBA was announced in January, kudos rolled in fast. “That was the first time I was starstruck of my sisters,” Erica says. (Chiney, a Sparks teammate of Nneka’s who is sitting out the 2020 season for medical reasons, is an executive committee vice president.) “I was like, ‘Woah, this is the type of stuff that’s in history books.’ ”

Nneka appreciates the fanfare, citing scores of “incredibly validating and inspiring” messages that she’s received from women in all walks of life, praising the WNBPA “for what we were able to achieve.” In typical fashion, though, she is encouraged but not satisfied. “I feel as though what we were able to accomplish in this last CBA is certainly a stepping stone,” she says. “It’s a catalyst. It’s by no means the endgame.”

***

As the country began shutting down due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March, Ogwumike took shelter with her parents, Ify and Peter, at their home outside Houston. Her sisters opted to quarantine there, too, including Erica, who soon began accompanying Nneka on her exhaustive morning workouts. They ran sprints on nearby farmland, drawing quizzical side-eyes from cows, goats and pigs. They hurled medicine balls and performed Pilates in the hot sun. Sometimes Erica would move her yoga mat into the shade, but Nneka refused. “She’s very work-minded,” says Erica, 22, a former Rice guard who went in the third round of April’s WNBA draft but is currently attending med school. “She never has excuses. Even if I’m just joking about excuses, Nneka never makes them. That’s why she’s so efficient.”

This relentless drive no doubt serves Ogwumike well in handling her twin leadership roles on the Sparks, the only franchise she’s known after going No. 1 in 2012, and in the WNBPA. “It takes a lot of energy, a lot of your time,” says Sparks coach Derek Fisher, speaking from experience as a former head of the NBA players union. But Ogwumike discovered an entirely new gear in early summer, which she characterizes as “the hardest months, professionally speaking” of her life, when her days were consumed by constant phone calls and video chats about the status of the 2020 season. “People were hitting her up at all times,” Erica says. “I don't know if that’s just the job of the president, or it’s a Nneka thing, too. But she never complained about not having time to watch Netflix.”

Many hours were spent on Zoom sessions with each of the league’s 12 teams, updating membership at key stages of the return-to-play talks, like when the WNBPA fought against proposed salary cuts for a shortened 22-game schedule (and won). But President Nneka was also a constant presence in nitty-gritty planning meetings for the bubble. Jackson recalls Ogwumike’s attending several lengthy calls with league doctors, having requested that the executive committee be included in shaping COVID-19 testing protocol. Later on, Ogwumike and Bird arranged to speak with the head chef and nutritionist at IMG Academy, wanting to ensure that players would be properly fed.

It is hard to find a detail that doesn’t have at least a few of Ogwumike’s fingerprints on it. Once the suburban campus was chosen, Engelbert remembers Ogwumike’s quick inquiry about the availability of bicycles. Later the owner of Nek’s Nap Salon took charge in bringing two hairdressers into the bubble; both recently finished quarantine and now take appointments via the WNBA’s on-site app.

Jackson, meanwhile, credits Ogwumike for speaking out on a few particular Wubble fronts, including priority housing and childcare stipends for parents, and ample mental health resources for all players. “One of our first town hall calls for the new season was around mental health and wellness,” Jackson says. “We had that because Nneka raised [the issue] to me. She knew that folks were in need.”

Along with the rest of the executive committee, Ogwumike also pushed hard to secure league support for player-driven social justice initiatives, which was ultimately spelled out in the WNBA-WNBPA season agreement. “That did not have to happen,” Jackson says. “That’s not a typical negotiated term. That’s usually something you give to a task force to work on.” Several star players, such as Minnesota’s Maya Moore and Washington’s Natasha Cloud, opted out of the season to focus on similar causes. But those in the bubble have ensured that their voices are being heard, too, from wearing Breonna Taylor’s name on the backs of their jerseys to forcing the postponement of Thursday’s slate of games in favor of a “day of reflection, a day of informed action and mobilization,” as President Nneka announced in a union statement on SportsCenter.

“Our movement has found its momentum,” Ogwumike says. “This year has been a wake-up call, but we’ve always been in this moment. We’ve always been political. We’ve always been contradictory to norms. We’re a women’s league that plays basketball. We’re a women’s league that is 80% Black, with LGBTQ interwoven between, and a league that’s always spoken about things. We’re grateful for an opportunity to continue to bring light to who we are. We are in the conversation.”

Until this week’s historic walkout, at no point was the collective power of WNBA players more evident than when Sen. Kathy Loeffler (R-Ga.), a minority owner of the Atlanta Dream, criticized the league’s alliance with Black Lives Matter in a letter to Engelbert. The initial backlash was swift, as players condemned Loeffler and called on her to sell her ownership stake, and before long full rosters were wearing T-shirts to games to campaign for one of Loeffler’s election opponents, Rev. Raphael Warnock, whose campaign donations swelled as a result of the support. “Now we have people asking for VOTE WARNOCK shirts, which is kind of cool,” Ogwumike says. “It’s also another point proven, that women in sports can sell things.”

Asked about Loeffler in a July interview, Ogwumike doesn’t hold back. “There’s a reelection, so the transparency is obvious, I guess,” she says. “I would hope that there’s enough awareness for people to see that someone who adamantly insisted on politics not being in sports is being incredibly hypocritical. It’s unfortunate that Black Lives Matter is considered political. It’s a human rights issue, but it’s become political because it serves agendas. With that, if I were in a situation that didn’t reflect my values or my opinions, I would just leave. Quite frankly, if you don’t like it, then bounce. Is it that complicated?”

Ogwumike has a similar outlook about those who haven’t yet climbed aboard the WNBA bandwagon. The stakes have never been clearer than in the light of a national racial reckoning. “Supporting the WNBA is supporting Black women, and showing up for a game is an act of feminism, in the same way as showing up for a rally,” says Kagawa Colas. And increasingly more people are getting the message: Television viewership is up from the 2019 season—11% on ESPN and 18% on NBA TV, according to a league spokesperson—and sales on the league’s website store have skyrocketed 400% compared with the first two months of last season, largely thanks to popularity of those orange hoodies rocked by celebrities, athletes and scores of NBA players in support of the cause.

So, Ogwumike figures, any fans, sponsors, business partners and others still on the fence might as well just bounce. “If, after this period, you’re still not a part of the WNBA,” she says, “it’s too late for you.”

***

Each morning in the Wubble, Ogwumike takes a few moments to herself. She finds a comfy sitting space in her campus suite, which she shares with Seimone Augustus, and meditates, often alone but sometimes with the help of an app “if I’m feeling I need some support.” She writes in her journal, drawing inspiration from guided prompts, because “I like guidance and rubrics. That’s how I am.” (In one recent example, presented with the fill-in-the-blank sentence, BECAUSE I HAVE ___, I WILL GIVE ___, Ogwumike answered STRENGTH and POWER.) Finally, she drinks a full bottle of water.

The whole routine doesn’t take long, but it’s critical to helping her handle the usual array of interviews, meetings, COVID-19 testing, film sessions, workouts, practices/games, and treatment that comes next. “It allows me to set the tone for how I can receive the day, and how I tackle the day,” she says. “Whether whatever happens is expected or not, it really puts me in a good headspace to be the best that I can.”

To be sure, there is plenty to tackle. Her phone buzzed nearly nonstop for the first week in the Wubble as players sought out President Nneka with every little issue; the rate of calls has slowed down since then, but Ogwumike says she still greets opponents with a friendly, “You can hit me up if you need me!” when they cross paths on campus. And that is without considering her on-court responsibilities; with Ogwumike ranked second leaguewide in field goal percentage (.606) through Thursday, the Sparks had reeled off a seven-game winning streak to pull within a half game of Seattle for first place.

When it comes to her stable of sobriquets, Ogwumike says that a common trait underpins them all: “Resilience. That’s what the constant Nneka is.” It’s why a self-described basketball “late-bloomer,” who recalls being “frightened” and “not particularly skilled” when she began playing in grade school, blossomed into a college all-American and the 2012 Rookie of the Year. It’s how someone can power through Pilates in the Texas sun and still have enough energy for a full work day’s worth of union calls.

Ask others what qualities of Ogwumike’s stand out most, though, and a variety of responses come back. Engelbert sees the same qualities that she looked for in new hires over three-plus decades at Deloitte: “emotional intelligence, thinking quickly on your feet, and grace under pressure. Nneka really checks these boxes.” Bird singles out President Nneka’s directness in diplomacy: “There’s not a lot of b------- to Nneka. She is who she is, and what she says usually goes.”

Kagawa Colas invokes a business book, Multipliers, which details how great leaders nurture and enhance the skills of those under them. “When they come in the room, ideas flow, they ask great questions, problems get solved,” Kagawa Colas says. “It comes down to doing more with less. That is women in sports right now. I think you’re seeing the results of Nneka being this natural multiplier type of leader. She can do more with less, because she knows how to listen and amplify people around her.”

She has strength. She gives power.

Case in point: Not long ago, Ogwumike presented Kagawa Colas with a list of entertainment items desired by WNBA players in the Wubble, particularly the handful of those with children, hoping to tap into her Wasserman agent’s connections for help getting the requests covered. The end result? A sizable chunk of the list—including a pool table, a foosball table, an Xbox, kid’s books, and jumbo Connect 4—will be soon shipped to Bradenton, courtesy of Ogwumike’s counterpart, NBA players’ union president Chris Paul. (A Slip ’N Slide and netted trampoline were requested but ultimately nixed for insurance reasons; everything will be donated to area charities after the season, Kagawa Colas says.)

The donations came from a fitting source. After all, it was Ogwumike who had seemingly put Paul on public blast for not answering her messages in early July, when both leagues were first entering their respective bubbles. “It’s just something I felt like tweeting,” she says. “Allyship from our brethren, it’s not an option. That's something that has to happen.” But communication among the fellow leaders has improved. Ogwumike credits Paul and NBA players for including the WNBPA in recent conversations around racial injustice, most notably with Michelle Obama, and she says he’s also reached out about getting some VOTE WARNOCK shirts. “I see the germination of something that could be very special in terms of allyship and how that allyship affects the WNBA and women in sports,” Ogwumike says.

One more step toward the endgame. As for what that looks like, and when the WNBA might get there? “Thousands in the stands, obviously higher pay, more eyes on us, more partnerships, more sponsorships, even better basketball, I see all of that,” Ogwumike says. “I have no problem knowing that I probably won’t be in the league when that happens, but I’m hopeful that I have a hand in that happening.”

The way President Nneka and others see it, the true impact of her signature piece of action won’t reveal itself until the next contract. “This CBA restructured things,” Bird says. “This one got us out from under the old regime, the old ways of looking at things. It’s going to allow for the next union leaders to negotiate something even more groundbreaking.” Whether Ogwumike will be around to lead those talks as a player rep is unlikely, although perhaps she will be involved in some other capacity; after all, she says her post-WNBA plan is to “hold a leadership position of some kind in women’s sports.”

But these are long-term concerns, and Ogwumike has enough on her daily plate. That is why the morning routine is so vital, and why she so values her down time at night in the Wubble. Cooking has been her “most therapeutic” pursuit in this regard, no doubt to the pleasure of patrons of Chef Nnek. But she also journals, listens to music and races Sparks teammates in Mario Kart on Nintendo Switch—riding against her players for a change. She used to exclusively choose Yoshi, but then she created an in-game avatar resembling her likeness. Who better to trust behind the wheel than Ogwumike, speeding full throttle toward the finish line?