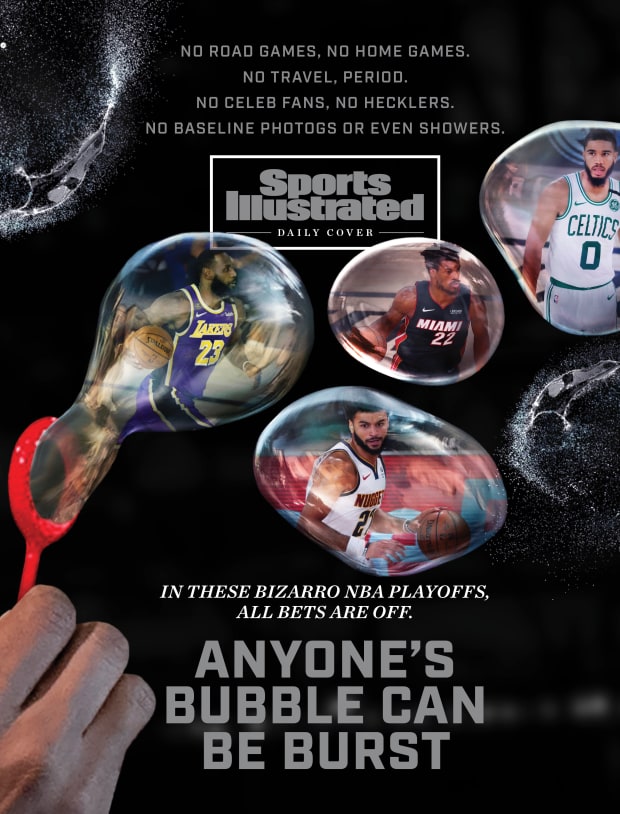

Any thought of a conventional NBA playoffs quickly went out the door once the league resumed play in the bubble. With no home-court advantage or travel, this has been the most bizarre postseason yet.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. — The shot went up and in, and public-address announcer Kyle Speller got excited: Three-pointer for the San Antonio Spurs! A Utah Jazz coach quickly tapped on the plexiglass surrounding Speller to remind him: Dude, we’re the home team. Speller hit himself in the head. The Jazz coaches laughed.

Welcome to the NBA bubble, where somebody is always the home team but nobody is ever home. The miracle is that in two months of bubble P.A. work, bouncing from home team to another without going anywhere, Speller made that mistake only once.

The NBA has staged the only kind of season it could, and that postseason has gone better than anybody could have hoped. The league also went to great lengths to re-create the arena environment, from virtual fans to recorded cheers to graphics and P.A. announcer calls that are specific to each team’s home arena. Without that effort, the games would seem sterile, like they were being played in a lab. But the NBA cannot replace the feeling an arena hopping with 20,000 people.

Speller has been the Nuggets’ P.A. announcer for 15 years. He knows that if Tuesday’s Game 3 between the Nuggets and Lakers were actually in Denver—and in late May—Peyton Manning and John Elway and Drew Lock would probably show up, making it the place to be in Colorado that night. Instead, the hype man must sell the illusion that he is firing up a crowd.

In the conference finals, Speller is the home-team announcer for both the Nuggets and the Celtics. It is his job to yell, “Let’s gooooo! Kemba Walker for three!” like he means it, and he does it well enough that Walker has pointed to him as if to say thank you. Fitting for a playoff where everybody is now at the same hotel—Gran Destino Tower at Disney’s Coronado Springs—Speller provides a concierge’s personal touch. When Milwaukee’s Wesley (Iron Man) Matthews scored, Speller yelled “I … am … Iron Man!”

It is impressive, detailed work, but it goes only so far. On TV, the games quickly start to seem normal. In person, it’s the difference between listening to a live album and attending a concert.

When the visiting lineup is introduced, nobody boos. During Heat introductions Saturday night, the players didn’t even run out when their names were called. There are no gasps when a player gets injured. After Toronto’s Fred VanVleet threw up an air ball in Game 6 “in” Boston, there were no Celtics fans to taunt him every time he touched the ball. When the Celtics won Game 7 “in” Toronto, they did not have to contend with Drake in the front row, talking trash.

When the Heat announcer declares there are “two minutes … dos minutos” left in a quarter, it is mostly a reminder of all the Spanish-speaking fans who would have attended the game if it were in Miami. Local flavor is missing. You can order your favorite childhood meal at a restaurant, but it’s not the same as grandma’s recipe.

There are no free taco giveaways, no T-shirt guns, no photographers along the baseline, no fans crowding the court, no playoff-induced claustrophobia. Timeouts can seem eerily quiet. On Saturday night, as Miami’s Duncan Robinson missed the first of two free throws, the only person heckling him was Enes Kanter on the Celtics’ bench. In his plexiglass-enclosed booth, Speller can hear only so much; once, when a referee forgot to turn on one of his mikes, Speller had to read lips to find out the result of a replay review.

This all clearly has an effect on the basketball, but it’s hard to know exactly what that effect is. Playing in the same small arenas again and again should help three-point shooters, who don’t have to worry so much about depth perception and can grow comfortable with the backgrounds. All four remaining teams are shooting more three-pointers per game than they did during the regular season. But Miami and Boston are making them at a lower clip.

The biggest challenges here are not physical. They are emotional and mental. Lou Williams of the Clippers was ridiculed for eating chicken wings at an Atlanta strip club in July, and then again when his team blew a 3–1 lead to the Nuggets. Fewer people listened to what he said after his team lost: “I haven't seen my daughters in 68 days.”

When the Clippers lost, coach Doc Rivers shot down any conversation about the bubble getting to his team, saying, “It didn’t get to Denver.” This is true, and maybe that is the point: The NBA champion will not just be the team that plays the best. It will be the team that navigates the bubble the best.

NBA players are like many Americans who have good jobs and their health in 2020: They understand they are lucky, but they still miss their old lives. Every day is a battle to create normalcy, to forget the life they used to lead while they make their way through this one.

Inside the bubble, time seems to stretch forever, yet people are prone to impatience. One evening, I got on a bus to go to the Western Conference finals, only to realize the game that night was actually the Eastern Conference finals. It didn’t matter. Celtics coach Brad Stevens did not know it was Labor Day. More than one player has mentioned a game “tomorrow” before realizing the next game was actually two days away.

Normally polite Miami coach Erik Spoelstra got annoyed by what he felt was repetitive questioning by citing everything he had said “for the last five minutes.” Same bus, same arena. Of all the special deliveries that arrive in the bubble, from French press coffee makers to wine to microwaves to more wine to pickleball rackets to even more wine to comforters (the blankets in Disney’s Coronado Springs are so thin, they ought to say “Kleenex” on them), it is unlikely that anybody has needed GPS.

There have been small sparks of playoff tension. Boston’s Jaylen Brown bristled at Toronto coach Nick Nurse’s in-game antics and complained loudly from the bench Saturday about a hard foul by Miami. But everybody is in the same hotel, every game now is in the same building—The Arena—and everybody is essentially on top of each other. Players are competing against each other yet are weirdly in this together.

Toward the end of Anthony Davis’s press conference after a recent game, James, his Lakers teammate, sat on a chair behind him, saying “last question” repeatedly in an attempt to end the proceedings. James was not annoyed with Davis, his team’s performance or the media. He wanted to go back to the hotel so he could take a shower. A few nights later, the Lakers’ JaVale McGee walked through where Michael Malone was holding a press conference, because he was headed for the weight room, which was in the same room.

Then there is the lack of travel. In normal times, the Nuggets would have taken 11 flights before Game 1 of the Western Conference finals. This year, they took none. That helps explain why the Nuggets are the first team in NBA history to come back from consecutive 3–1 deficits. The journey is not quite as exhausting.

A conventional NBA playoff series has an ebb and flow that is tied directly to home-court advantage. As the Clippers blew a Game 5 lead to the Nuggets, they knew they would not have to go on the road for Game 6. Marcus Morris said the next day, “I don’t think none of us want to go to Denver. So we kind of feel good about that. That (crowd) plays a major factor in games.” The Clippers went on to lose Game 6, and then Game 7 at “home.” It is fair to wonder whether an actual L.A. crowd would have changed the environment in Game 5 or Game 7.

As Speller points out, it’s not just about the crowd in Denver. It’s the altitude, too. James memorably suffered from cramps in a hot San Antonio arena in the 2014 Finals; who knows how a 35-year-old, 250-pound man would handle a fourth quarter in Denver?

NBA playoff performances largely come down to concentration. James is clearly locked in. The Clippers and Toronto star Pascal Siakam were not. The Staples Center can feel like the center of the world on a playoff night. The small arenas at the ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex do not.

The social justice messages on the back of the jerseys might look performative on TV. But inside the bubble, Black Lives Matter is even more prominent than outsiders might realize. On many nights, the most powerful moment is the national anthem, when players, coaches and officials get on one knee, wearing BLACK LIVES MATTER or VOTE T-shirts, and lock arms. Somehow, the image is even more powerful when Miami plays, because Heat backup Meyers Leonard chooses to stand for the anthem, and he does so alongside his kneeling teammates with no repercussions for anybody. It is a welcome change from the sniping and divisiveness we see so often elsewhere.

The Lakers’ Danny Green likes to begin his media sessions by reminding people “why we’re here” and naming victims of police brutality. After games, players routinely change into clothing that features social justice messaging.

During a timeout during Game 2 of the Eastern Conference finals, while Ella Mai’s “Boo’d Up” played over the speakers, the virtual fans on the big screens were replaced with STAND UP, BLACK LIVES MATTER, ENOUGH. Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” is often played during timeouts.

NBA players are both removed from the real world and acutely aware of it. To play well, they must keep perspective all day and then convince themselves, when they step on the court, that all that matters is basketball. They must fight the natural tendency to want to get the heck out of here, because the only way to do that is to lose. The team that wins the whole thing will have earned it. The championship rings should have a large bubble in the middle, as a reminder of this strange journey. It is hard to get where you want to go when you feel like you can’t go anywhere.