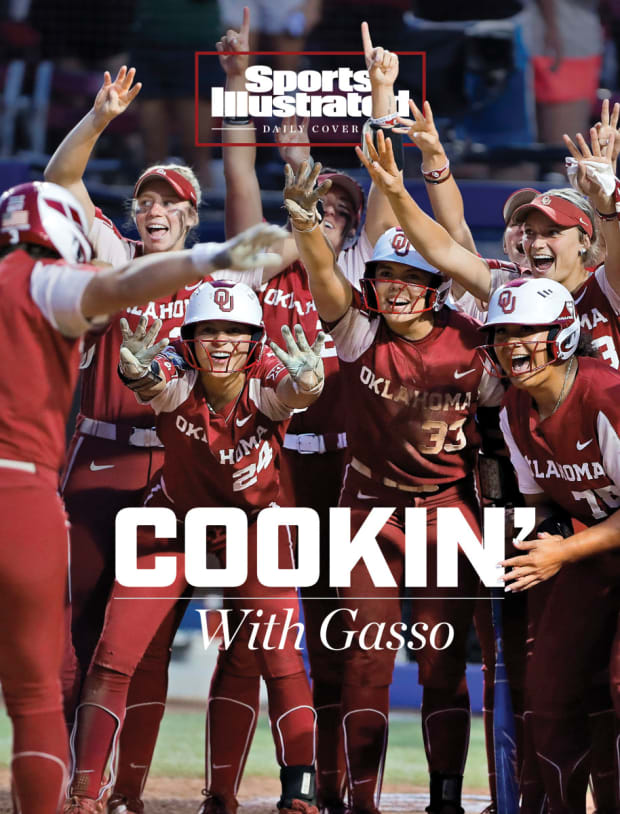

The pressure as defending champs never got to the Sooners, who won a second straight WCWS title behind a relentless coach and a whole lot of practice.

Oklahoma spent an entire year trying not to think about it.

From the moment the Sooners walked off the field as champions at USA Softball Hall of Fame Stadium on June 10, 2021, they were surrounded by chatter that their next season could be the best in the history of college softball. They had just finished one stellar campaign. But with much of their core returning and even more impressive talent incoming, their next year seemed poised to be better still. Anything less than a second consecutive title—which would be four in seven years for Oklahoma—would be considered a disappointment. The questions chased them everywhere: Where will this rank among the all-time great seasons? How impressive is this dynasty? What would it mean for a team this good to possibly lose? The Sooners heard it all, and they turned their focus inward, looking instead at the work that was in front of them. They tried not to think about it.

But when the final out was recorded for this second consecutive championship—when Oklahoma finished its historic season by defeating Texas, 10–5, in Game 2 of the Women’s College World Series on Thursday—the calculus shifted there somewhat. If they wanted to think about their greatness, their legacy, their impact on the sport—perhaps here was a moment to do so.

First, though, they had to celebrate.

Alonzo Adams/USA Today Sports

How best to describe the Sooners’ dominance in 2022? There is the simple power of their record: 59–3. There’s the fact that an incredible 40 of those wins required the run rule—meaning the game was cut short due to a lead of eight or more after five innings—while no other team had more than 20 such games. There is their best-in-class offense; they led the country in scoring with more than nine runs per game. (If that seems impressive on its own, consider that they had fewer innings to score than anyone else, because they had to invoke the mercy rule so often.) And, oh yes, behind national Freshman of the Year Jordy Bahl and redshirt senior transfer Hope Trautwein, their pitching also led Division I with a 1.05 ERA.

It is a dazzling collection of talent, up and down the roster, arguably the best ever. But there can be no debate as to the crown jewel: Jocelyn Alo. She is the all-time home run queen. She has been the National Player of the Year twice. She is the first hitter ever to have three seasons with 30 or more home runs. She looked like an incredible, unstoppable force last year, when she hit .475 and slugged 1.109—the sort of performance that seems hard to repeat and all but impossible to improve upon. Or, at least it did until this year, when she hit .515 and slugged 1.228. She has stood out more from her peers in D-I than Barry Bonds did from his in MLB during his best season, in 2002. To look just at her numbers is to think you have been tricked with stats from a video game. To watch her day in and day out has been to question the very parameters of the game.

Which, of course, would pose enough of a problem for opponents if she were the only threat in the lineup. But the hitter behind her, Tiare Jennings, also ranked top 10 in D-I in slugging. And the hitter behind her, Grace Lyons, also ranked top 10 in D-I in slugging. That general idea carries down to the bottom of the lineup: only very slight variations on the theme of excellence. There is nowhere for an opposing pitcher to seek refuge.

And then there is their coach. This is the sixth title Patty Gasso has won since coming to Oklahoma in 1995; it is her fifth time in the finals in the last six tournaments. It is the second time she has won it all back to back. Asked afterward how she felt about the term “dynasty”—about the comparisons to UConn women’s basketball or Alabama football or any other—she demurred. But from the outside, what she has built can’t be described otherwise. She has made the program into a powerhouse. And the 2022 Sooners are its most spectacular edition yet.

Sue Ogrocki/Associated Press

Gasso is just as comfortable at USA Softball Hall of Fame Stadium as her record implies—15 trips to the WCWS here, eight times in the finals, six championships. But the memory of her first time at the stadium for the tournament still feels fresh. It was before she got the job at Oklahoma, before she knew she would ever have a chance to coach in D-I, certainly before a simple mention of her name could automatically elicit cheers from thousands. Her first time here was not to coach. It was simply to watch.

Gasso was working beyond the high school level for the first time—the coach at Long Beach City College, a two-year institution in her native California, where she had been hired at age 27. Her athletic director, Mickey Davis, had seen a certain quality in her: “You just know when someone has it,” Davis says. “And the potential Patty Gasso had was just beyond the borders of imagination.” Davis wanted to nurture that potential. The best way she knew how was to let her see the pinnacle of college softball up close—to bring her to the WCWS in Oklahoma City.

“She would bring me out here, and I would watch,” Gasso said before the championship series of her trips to Oklahoma City with Davis. “There were 2,000 people here. I'm like, Oh, my gosh, look at all these people. This is crazy.”

Before she went into athletic administration, Davis had a Hall of Fame softball career as a player, and she seemingly knew everyone at the WCWS. She introduced Gasso to D-I coaches and staffers—listening as her young hire went out of her way to meet as many people as possible and ask them questions. Gasso knew she had a lot to learn. (In more ways than one: Davis still laughs remembering their first trip to the WCWS, when Gasso tried to call her husband back in California and accidentally placed an overseas call to Japan, getting hit with a charge they had to explain on their expense report.) But the coach wanted to soak up all that she could.

“I thought it was important to see what she could aspire to be not only from a coaching standpoint, but from how the teams were so wonderfully talented and from the excitement and the lure of the College World Series,” Davis says. “I knew that one day Patty would be there. I just knew it.”

What stood out the most to Davis about Gasso was how she ran practices. That was how Davis liked to evaluate any coach. It was one thing for someone to be successful with in-game strategy, or to turn on the charm during recruitment, but to know just how to push a team to improve without totally breaking them down was special. And it was one area where Gasso shone. Davis could see the amount of work she put in: Gasso had a plan for every minute of every practice. She was always honest and direct with players, but she was kind and she worked to know and support them simply as people, too. Davis loved Gasso. But she didn’t think the coach would have many years with her at Long Beach City College.

After Gasso’s fourth season in Long Beach, Davis got a call from Marita Hynes, then a senior associate athletic director at Oklahoma. Hynes wasn’t calling about Gasso: She respected Davis’s expertise, given her long tenure in the sport, and wanted to ask whom her top three picks would be to fill a coaching vacancy. Hynes told her to think big, anywhere in the country, no matter how experienced. But Davis told her she didn’t need to bother with three names. She wanted to recommend just one—and no, this coach had never worked for a four-year school, certainly never in D-I, but she was the one. She was Patty Gasso.

“This talent—this potential—needs a home to grow,” Davis remembers telling Hynes. “You’re going to be successful, and I don’t mean conference championships. I mean national championships.”

Almost three decades later, Gasso still makes what feels like an annual pilgrammage to the WCWS, much like she did with Davis. It just looks a little different now.

Sue Ogrocki/Associated Press

Gasso entered this year with personal experience of how difficult it is to win back-to-back championships. Her roster did not. (Although it very well might have if the 2020 postseason had not been canceled due to COVID-19.) This was so much of what Gasso had to work to impart to them: You already know what it means to be the best. Now you have to learn what it means to keep it going. This team was going to win, and win often, and win by a considerable margin. There was simply too much talent on this roster for anything else. But that situation brought its own challenges: They could not afford to be affected by the pressure or risk complacency.

“Coach Gasso does a really good job of holding us to really high standards,” Alo said. “There was one point we were run-ruling teams, and we felt like she was just grinding us, and we were like, But we’re run-ruling! That’s just the standard. … I feel like that's what sets us apart.”

True to what Davis saw from Gasso in the early 1990s in Long Beach, a large part of the Oklahoma coach’s style comes from how she runs practice: “We have really good practice plans, very detailed practice plans, and we don’t practice like any other team in the country,” Alo said. “We’re going to put on our pants, and we’re going to get our hands dirty, and we’re going to go to work.” While so much focus has been on the team’s historic offense, there’s that stellar pitching, too, and the way the two sides face each other in practice is “iron sharpening iron,” Alo said.

They practice everything.

Even skills that don’t seem likely to come up very often. Like, say, home run robberies: A pitching staff that averages less than one run per game does not allow many home runs. (They gave up 15 across their 62 games.) But Gasso makes sure her outfielders practice those catches all the time—how to read the flight of the ball, when to time the jump, where to position themselves against the wall. All of it. Just in case.

In the first inning against Texas on Thursday, Bahl got into trouble early, allowing two quick runs to score. A runner stood on third with two outs, and Longhorns slugger Courtney Day sent one deep to center, all the way to the wall. “I was a little sick to my stomach,” Gasso said afterward, Oklahoma’s press conference. But Sooners center fielder Jayda Coleman was there. She hadn’t made a catch quite like that in a game. But she’d sure practiced it.

“We practice that all the time,” Coleman said. “It's crazy that it actually showed up in a game when we really needed it.”

It was a momentum-swinging, one-of-a-kind, game-changing highlight. And it looked familiar to Oklahoma catcher Kinzie Hansen.

“She's robbing all of our home runs at practice all the time,” the junior said, grinning. “So when she does it in the game, it’s almost like routine.”

This has been much of what has made their 2022 even better than their ’21—continually grinding away on the little things. Yet getting the most out of practice is just one part of the equation. The motivation in the locker room, on the bus, in the dugout? That’s Alo—a fifth-year senior who has not been afraid to use her voice as she closes out her college career.

Brett Rojo/USA TODAY Sports

“She gets so fired up for her family, for our team. She’s the most confident young lady I've ever met in my life, to the point where you’re like, O.K., don’t say that, Joce.’ But that’s her,” Gasso said. “She's just really raw with excitement and love for the game. … To see that and to be around it—it just bleeds all over our team. They all want a little piece of what Joce has.”

Her teammates know they are playing alongside one of the best of all time. (“Learning from Joce on how she plays the game and attacks hitting, it's incredible,” said All-American shortstop Lyons. “I learn from her every single day.”) The underclassmen have been watching her from a distance in awe for years. The upperclassmen have seen her develop up close—getting to witness her growth from a raw talent to the best power hitter in the history of college softball. But more than her skill, more than any of the towering moon shots or the gaudy statistics, it is her passion that stands out to her teammates.

Gasso put Alo in the field for the final inning Thursday—the designated player typically sticks to hitting, but her coach wanted to give her one last chance to soak it all in, and the fans one last chance to appreciate her. She pulled Alo off with two outs for a curtain call. The greatest hitter in the game—one who galvanized the sport and redefined potential at the plate—walked off with tears in her eyes to a standing ovation and a dugout full of hugs.

And then Gasso sat back for the final out of a championship season.

“It’s surreal,” she said. “The game goes by fast, and there's highs, and there's lows. You just watch. I sit back like a fan. That’s what I do.”

For a moment, the emotion proved overwhelming, and Gasso took a second to collect herself. After a year of trying not to think about it—of doing her best to make sure her team did not end up swallowed by its own power—she had all of it in front of her, the questions about her legacy and the meaning of a dynasty and how this final out matched up with all of the past ones. And then she finished her answer the only way she knew how.

“You ask me to compare,” Gasso said. “You ask me what it feels like. It feels like something we do every day at practice.”

• 50 Years of Title IX: How One Law Changed Women’s Sports Forever

• The Return and Rebirth of the WNBA’s AD

• The Spirit of the NWSL As It Turns 10