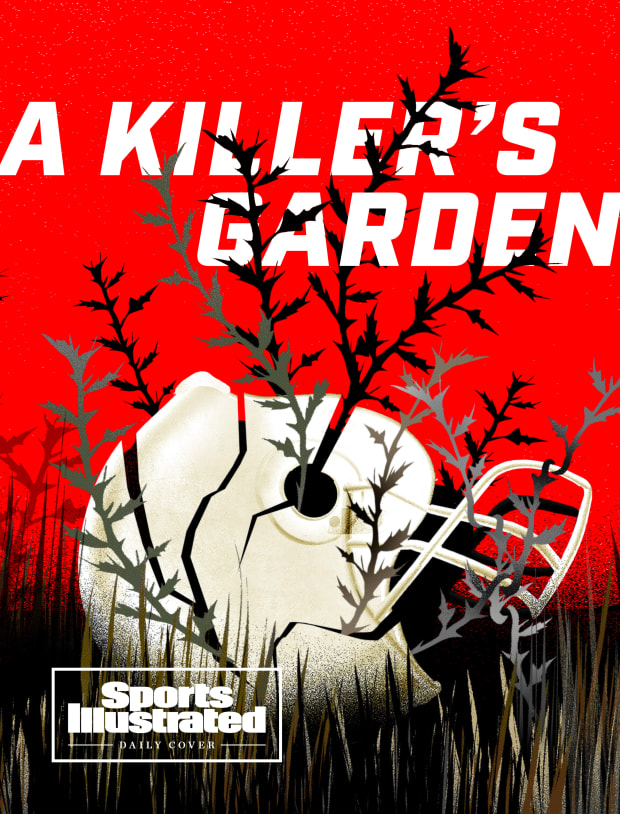

An unspeakable assault by a former NFL player has forced those close to him—a young son, a father, a mother—to consider unimaginable questions about the shadows in which we live.

Editor’s Note: This story includes references to suicide and suicidal thoughts. The number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-TALK, or you can text HOME to 741741 for free, 24/7 counseling.

A man and his wife have been forced out of their house and into a hotel, where now they lean on people who feel like home. Ding. The elevator doors open and the man limps out into the hotel lobby. The lighting really brings out the gray in his hair. He passes his wife, who sits in a wheelchair, talking with a family friend, and he eases into a seat, his substantial frame filling it in total. He looks tired. As he sits and his sweatpants rise to his ankles, a tan bandage shows on his left foot and ankle, wrapped thick under his black Crocs. About two years ago, after driving into a forest to reach a fishing spot, he stepped out of his truck and into a hole, gashed his foot on a rock, and lost his balance as he lunged backward out of the hole. That’s when he did the real damage: While catching himself, he closed the truck door on himself, carving the ankle deep. Left a gash there almost as big as a baseball and exposed everything down to his Achilles. The wound kept getting worse, no matter what his doctor did to treat it. The foot could’ve been lost. Finally, he drove 30 minutes north from Rock Hill, S.C., to a wound center in Charlotte, for a second opinion, and there a one-hour outpatient surgery helped start the healing.

The wound has been improving ever since, but it’s still there, and he’s still a regular at the wound center. The thing is taking forever to heal, and sometimes the healing hurts more than when he got the wound in the first place.

Back in the hotel lobby, the automatic front doors whoosh open and a young boy runs in carrying an iPad. “Papa!” he yells to the gray-haired man with the healing wound. His Air Jordan 1s are blurs of blue and red and white and purple and yellow and black. Kid’s got style. Distressed jeans. Gray hoodie. A faux-hawk fade.

Alonzo and Phyllis Adams, 65 and 66, respectively, get hugs from their 7-year-old grandson, P.J., then the boy plops onto a couch to play a video game, a hero fighting a city full of bad guys. His mother, Ashley Clemons, 32, trails in behind him, wearing black sneakers, a cheetah-print dress, denim jacket, clear-framed Wayfarers and fresh braids. She sits, smiles, says hi. Pregnant and about halfway to term, she looks just as tired as Alonzo. P.J. keeps asking her to go to Papa’s house, but they can’t do that yet, and might never again, because of what happened a few weeks earlier. The Adamses’ home requires repairs. Everyone needs healing.

“My goal,” Ashley says, “is to instill all the positive things into [P.J.], so he’ll know that his dad did love him—but at the same time, as he gets older, to understand how strong your mind can be.”

P.J.’s father, Phillip Adams—the youngest of Alonzo and Phyllis’s three children—is at the root of all this suffering. Around 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday, April 7, the NFL veteran of six seasons put on a dark hoodie, camouflage pants and a black motorcycle helmet; he armed himself with two automatic rifles, mounted a four-wheeler, pulled out of the gravel driveway at his parents’ home in Rock Hill and drove a mile down Marshall Road, a quiet stretch of residential country asphalt. Phillip waved to a neighbor and eventually turned into the woods, taking trails through the trees, toward a sprawling ranch-style brick mansion in the middle of a heavenly estate. There, in the yard, he encountered and shot two HVAC service contractors, James Lewis and Robert Shook. Then he entered the house. While Shook called for help outside, Phillip cornered Robert Lesslie and his wife, Barbara, in their home gym, along with two of their grandchildren, 9-year-old Adah and 5-year-old Noah. By the time deputies arrived, fewer than 10 minutes later, Phillip had vanished. Everyone was dead except Shook, who’d been shot six times and would undergo multiple surgeries before succumbing to his injuries three days later in the hospital.

The afternoon of the shooting, P.J. was in Miami with his mother and her boyfriend, on vacation for spring break. “Just a regular day at the beach,” Ashley says. “Meanwhile, all hell was breaking loose.”

Alonzo had driven Phyllis that morning to visit his sister, an hour north in Gastonia. On the way back that evening, in their white minivan, they noticed a large police presence on Marshall Road, but when they got home everything seemed fine. Phillip was reading in his room. It was later, after Phyllis was in bed, that Alonzo heard voices in the yard and opened the door to find chaos. He thought he was experiencing a flashback to the time he served with an Army special-ops unit. Men in combat gear trained their guns on him. Hands up! Turn around! Don’t move!

Cuffed and seated on the ground in his front yard, Alonzo begged police to be careful with his wife and son. “Just try to get them out!”

Placed in a cruiser and driven a mile down the road to the Lesslies’ driveway, where more patrol cars circled, Alonzo, confused, asked questions that nobody answered. He sat alone for what seemed an eternity before finally a detective appeared, told him that Phyllis was safe and said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Adams, but your son is deceased.”

By then police had spent hours begging Phillip to surrender, calling out on bullhorns, eventually sending in a robot. They tore the house apart. And then, sometime between when they extracted Phyllis and when they charged into the home themselves, around 2:30 a.m., Phillip picked up a .45-caliber handgun and turned it on himself, his seventh and final victim. He was 32 years old.

York County Sheriff Kevin Tolson said it best, at a press conference the day after the shooting: “Nothing about this makes any sense.”

The HVAC repairmen, Lewis and Shook, were each a father to three children—Lewis as a single dad, Shook as a husband of nearly two decades. They were mourned by hundreds of friends, family and coworkers at their funerals. Then there were the Lesslies, whose lives revolved largely around the First Associate Reformed Presbyterian (ARP) Church, in Rock Hill. Robert was an elder at the parish. Barbara, known as “Mrs. B,” was a true believer, passionate about teaching the Bible and endlessly creative in how she did it. She sang in a trio at ARP and performed skits alongside the wife of U.S. Representative Ralph Norman (R), a Rock Hill native and decades-long friend of the family. Adah and Noah had inherited the same love for worship, particularly through music. Their father, Jeff—Robert’s son—was a volunteer singer and guitar player at the ARP early-morning service, and Adah was already starting to help lead the singing on some Sundays.

Robert’s death, though, is what truly shook Rock Hill, where people still talk about him like a saint, or a guardian angel. Seventy years old, but with the verve of someone 20 years younger, he’d spent decades as an ER doctor in town and then founded two of his own medical practices: an urgent-care clinic and a hospice clinic. Those in his orbit describe his work in terms that sound near miraculous, suggesting that he had a special ability to diagnose cancers and disorders that other doctors had missed, to always stay cool under pressure, to thrive in crisis. At the same time, he was a regular presence at Camp Joy, a nonprofit run by the church for disabled teenagers. He wrote prolifically, publishing hundreds of newspaper and magazine columns and more than a dozen books.

On the Lesslie estate this spirit took physical form. In the early 2000s, Robert purchased some 50 acres of woodland on Marshall Road, and he spent the next 20 years making it a personal paradise. Ponds. Hiking trails. Clearings with pavilions. Framed beehives for harvesting honey. An orchard bearing apples and pears and muscadines and blueberries and blackberries. A garden of all manner of produce. A nursery of young trees growing from shoots he’d spliced from others and nurtured in the ponds.

You can’t see much of it from the road, all tucked away behind fences and a gate, past the large white cross in the front yard, but those who’ve been on the property say it’s wonderful. The Lesslies regularly invited their church congregation there for picnics, “and every time you went,” says Barry Dagenhart, the ARP pastor, “you’d see something else [Robert] had done.”

“He was a renaissance man,” Norman says of the friend who taught himself how to play the bagpipes, just for fun. “He treated anybody and everybody—didn’t matter what time of night you called him, he was there. So the shocking part was the tragedy and the cruelty of how he died.

“And then, of course, the children. Nobody will ever get a handle on that.”

Unable to process what those other families must be going through, Alonzo Adams prays for them and does what he can for his own. He’s old friends with grief.

Phyllis was once an elementary teacher, the kind that kids loved, standing up on tables and throwing bean bags, singing and dancing. “Energizer Bunny,” Ashley says. Driving to school one morning 12 years ago, maybe a mile from home, Phyllis spun out on a gravel road. She lost control at the bottom of an incline that led into a curve, and her car cleared a ditch on its way into a tree. Phyllis was thrown across the vehicle, head-first into the passenger door, and she was left paralyzed from the chest down. Afterward, she couldn't lift her arms past her shoulders, but she remained joyful, thankful for her life. Alonzo, a long-haul trucker, shifted to local routes and took care of her.

He’s got his share of problems, too—defibrillator in his heart, deteriorating lower back and bad knees, plus that ankle—but he speaks of these as minor inconveniences. Alonzo talks aspirationally about how much Phyllis prays, and how maybe if he was more like her he’d be stronger. He smiles a lot and cracks jokes, wanting others to feel comfortable, his voice wheezy and high and friendly, even as he endures the unimaginable.

He tries not to let all the questions about Why? consume him. But it’s hard not to be consumed. As he sits in the hotel lobby, he has 51 missed calls—from family, from friends, from reporters. He can’t delete voicemails fast enough to keep space in his inbox. He assumes that the endless flood of text messages explains why the rest of his phone has suddenly quit working, too.

He focuses instead on all the things his family needs—on keeping the mind occupied, the heart distracted. Like making funeral arrangements and getting Phyllis to her doctor’s appointments and coming up with some plan for the house.

Phyllis doesn’t know whether she can go back to their home on Marshall Road. There will be time to decide, though. Repairs will take a while.

“It’s such a f---ed up situation,” says Ashley, who’s still not sure how to process it all. “You harmed children. Children in the same age group as your child.”

She knew from the beginning that she’d have to explain everything to P.J. But how do you tell your child something like this? How do you help him move forward? You don’t want to defend a murderer, a killer of children; you also don’t want your son to think his daddy was entirely bad. Life’s hard enough without that kind of shadow.

Ashley didn’t know how to make sense of it all herself. She’d seen Phillip through some of the hardest moments of his life. In college, after Phyllis’s accident. Through the NFL, where he suffered a horrific injury during his rookie season with the 49ers, his broken ankle tearing through the skin. It should have ended his career, but he did everything possible to heal his body. “I’ll never forget his drive,” she says. “All the stuff that was available to him, he used.” She watched for six years as he was signed and released, signed and released, sometimes within the same week, pushed and pulled around the country, from San Francisco to New England, Seattle to New York. It hurt like hell, the disposability of it all, and pissed him off, but never anything like this. Nothing ever made her think he could do this.

The mystery must wait, though. Time and hindsight will bring more clarity. For now there are other priorities, other questions. Terrible questions about what exactly sons inherit from their fathers. About the impossibility of squaring Phillip’s actions with the man everyone thought he was. About what can be done for those left behind, and about all that wasn’t done for him. By him.

That’s where her attention goes. To those questions. To P.J. “I’m the one he looks toward to fix everything,” she says. “I don’t know how to fix this.”

Really, though, there is no fixing, only surviving. Ashley kept the news of Phillip’s death from P.J. for a while, letting him enjoy the last couple days of vacation. They returned from Miami on Saturday. A few days later, she started by breaking down the word “harm” for him. She said: “If you hit your arm on a table, or you run into a wall, you’re hurting yourself. You’re causing harm to yourself. Your dad caused enough harm to himself to no longer be here.”

She told him: “Whatever you do, don’t hurt yourself. Sometimes your mind can think bad things. [Your dad] was battling with some mental issues that caused him to make a bad decision.”

She didn’t tell him about the harm his dad had done to other people. Not yet. She took P.J.’s iPad and disabled Google—anywhere he could stumble across coverage of yet another mass shooting, the 154th in the U.S. in 2021. She screen-recorded YouTube videos of Phillip’s playing days and saved them to a special folder where he could watch without interference from the morbid context. She got off the internet herself, too.

P.J. was supposed to start football practice on the Sunday after he got back from Miami. He already had his uniform, his last name on a jersey. But for Ashley it was “just a little too close for me.” She didn’t know how other parents would handle seeing the block-letter ADAMS on his back, on the field alongside their kids. In the end, she decided her son wasn’t going to play this year. To P.J., she blamed the decision on the pandemic. “We’ll play next year.” But she’s not yet sure if that’s true.

More than anything, she stressed to him: “It’s O.K. to be sad. And it’s O.K. to be angry. However you’re feeling, just pinky-promise me you’ll always tell me how you’ll feel.”

He pinky-promised.

After Phillip Adams moved back in with his parents, into the house he grew up in, in his final months, he didn’t say much. From afar, Ashley thought the move signaled something terribly wrong, but Alonzo says his son was making plans to build a new house in the area. He had plans, was the thing. And he seemed happy enough. He had two nice cars. He spent his days riding his four-wheeler through the fields and the woods that surrounded him. He talked about wanting more children.

And then there was his garden. Tucked away in a field maybe an acre in size, a couple of miles from home, down a long one-lane dirt road, in an area called Edgemore, you might not find it if you don’t know where to look. But it was Adams family land. Alonzo was raised here, in a little white house that still stands along the road, and decades ago he would run through the woods, play in the creeks and work in the fields. “We grew up on the land,” he says. “We picked cotton. It was our own cotton, though.”

They grew peaches, too, and corn, walnuts and grapes. “It was tough work,” Alonzo says. “That’s why I started playing football—to not be on the farm.”

A generation later, Phillip returned to Edgemore to find life after football. The garden “was his peace,” Alonzo says.

One day, the week before April 7, Alonzo’s cousin Dwight Sterling was in his driveway out that way when Phillip roared by on his four-wheeler, kicking up a cloud of dirt. Man, this dude didn’t even stop to speak, Sterling thought.

“That’s not how [Phillip] was raised,” Sterling says. “You pass one of your kinfolks, you stop and have a conversation.”

Sure enough, Phillip soon returned. “Hey, man!” he said. “I saw you! I was just thinking about something else!”

They got to talking about Phillip’s garden. He’d decided to start it a year earlier. It spanned some 200 square feet, the beginnings of his vision for a full-fledged farm. “He wanted to start a market,” Sterling says. He had plans. “He was going to offer fresh-grown food—no chemicals—to the inner-city kids. He had a great concept. He would say, ‘We need to take better care of our bodies.’ ”

He grew tomatoes, collard greens, okra, squash—“mostly the common vegetables,” Sterling says.

But growing a garden takes more work than one might imagine. “He had a rough time because he didn’t know how to farm,” Sterling says. “He was just digging up the ground and putting the seeds down. But you know, it’s a little tougher than that.”

Sterling had a garden out here years ago, too. “If you don’t maintain the weeds, it’s just not gonna work,” Sterling says. “If you get more weeds than plants, now you’re watering the weeds.” Leave them there too long, “they can choke out the plants,” he says. They’ll take all the plants’ water, and then “they take the roots.” Pull the weeds too late, you’ll take the plants with them.

The solution is to plow. “People think you just plow the field at the beginning,” Sterling says. No. “It takes patience. If you can get that, you can get it under control.” The plants are safe when their roots become stronger than the weeds. “Once the plants get big enough, they’re O.K.,” Sterling says. “If you can control the weeds a little bit, you’re gonna win that battle.”

That is, “if the deer don’t eat them all.”

Sterling had done everything right. Plowed, weeded, watered. He had a scarecrow, even lined the area with soap and urine—“everything that people’d say.” Then one day he came home and saw seven deer, standing there. “Just looking at me like, Thank you,” he says. “They ate my garden up.” They’d destroyed everything. Sterling wept. He quit gardening.

Phillip likewise struggled with the weeds and with the deer. “Didn’t have a clue what he was doing,” Sterling says. Even still, he was trying, and making plans to expand to a second plot. His enthusiasm was contagious; Sterling was inspired. “Man,” the cousin said, “this year, me and you, we’re going to do the gardening together.”

Phillip lit up. “Cuz! That’d be a good thing!”

Sterling had one question: “What are we gonna do about the deer?”

Phillip grinned. He’d just ordered a device with an infrared sensor to detect the garden-wreckers and scare them away with noise. He said: “I think we can beat these deer this year.”

These days, P.J. has taken to carrying around his iPad like a security blanket, with its home screen set to a photo of him with his daddy. He likes to keep their old pictures and text messages close. “They had some pretty dope convos,” Ashley says. “[Phillip] was always on him about reading. ‘Did you read tonight, buddy?’ ‘Daddy loves you.’ ‘Daddy misses you.’ A bunch of ‘I love you,’ ‘I love you back,’ ‘Hey, buddy, have a good day at school.’ Emojis.”

In mid-April, when the time came for Phillip’s visitation, Ashley took P.J. along with her to the funeral home behind New Mount Olivet AME Zion Church, where the Adams family has gone for decades. “I went back and forth about [whether or not to take him], until an hour before,” she says. Ultimately, she talked to P.J. “Do you want to see your dad?” He said Yes. Of course he did. “O.K.,” she said. “It’s going to look like he’s sleeping.”

She told P.J. he could bring along something to leave with his daddy. He chose a clay coaster that he’d made for Father’s Day one year, with his handprint in the middle.

That morning was for relatives only, beyond the police who filled the area. The victims’ families had issued a joint statement, saying “our hearts bend toward peace and forgiveness”—but strangers online had said angry and frightening things. Squad cars and police SUVs parked two or three to a block, with more in the lot.

Eventually, P.J. went to the casket, where his daddy lay in a suit and tie, looking like he was sleeping. The boy spoke to him, reached out and touched him, put the coaster in the casket beside him. P.J. had written on it: I love you, Dad.

The next day, Ashley took him to the funeral service at Mt. Zion, and then to the cemetery, guarded at its entrance by more police. “He didn’t like the gravesite,” Ashley says. “When they lowered the body, he wasn’t feeling that at all.”

P.J. used to see Alonzo and Phyllis every other weekend, but since the funeral he’s “obsessed with seeing them every day,” Ashley says. “I think it’s some type of coping for him. And for them. Because they get to see, like, little Phillip.”

P.J. keeps asking to go to their house.

That house. It’s a simple, warm, one-story brick rancher with a gravel driveway and a basketball hoop. Alonzo and Phyllis arrived in 1987. They raised their three children there—Phillip, Ryan and Lauren. They have neighbors now, but when they first moved in it was pretty much just them and the woods. “The deer used to come and lay down in the yard and eat,” Alonzo says. “We’d watch them out the window.”

They were thinking about leaving the house to Phillip in their will. Ryan and Lauren live elsewhere, with partners and their own children. They’ll visit, but they’ll never move back. Phillip loved it here.

Now, though? There’s a big blue dumpster in front of the house. Alonzo hired a crew, and they’re filling it with the detritus of the damage inside. Parts of a broken door. Sheetrock and plaster from the holes the robot punched in the walls. Pieces of bloodstained carpet and floorboards. Then entire walls. Alonzo decides not only to repair but to renovate. Make the place something new. Something to help Phyllis. “A drive-in shower and bathtub,” he says. “Get her back in without having those feelings of remembering. Maybe when she sees it, she gonna like it.”

Phyllis can’t decide, though. One day she’ll tell Alonzo they need to get the place fixed up. The next day she’ll tell him they need to move somewhere else. Roots are roots. But she might just need to pull them out and let them go.

Alonzo stays busy. “A lot of time when people have trouble, they idlin’,” he says. “When they by themselves.

“I just want to understand.”

Ashley says: “I have so many Whys and questions I want to know that keep me up at night.”

They say they don’t know why. Nobody seems to know why. They’ve heard all the theories, and they’ve come up with plenty of their own.

Maybe it was all those injuries. The gruesome broken ankle. God knows how many other painful blows.

Maybe it was the game, how he gave it his all and still felt the sting of rejection from all those teams. “He almost worked too hard,” says his agent, Scott Casterline. “He put way too much pressure on himself. And he was very critical of himself. He kept trying for perfection.”

Maybe it was the weight of growing up in Rock Hill, otherwise known as Football City, USA, because of all the NFL players it produces. Adams won a state championship with Rock Hill High and was recognized as one of the area’s best players. But life after football is a brutal adjustment. Casterline regularly sees former players struggle with the transition. “Loss of identity,” he says. “Those who played can get wrapped up in that too much.”

Maybe it was the devastation of opening and then losing a smoothie shop, Fresh Life, which lasted less than a year.

Maybe Phillip was inspired by a cult. The sheriff’s office announced on April 23 that investigators had found “cryptic writings” in some of Adams’s notebooks. Ashley, though, says he’d always written in notebooks. Nobody close to Phillip remembers him ever talking about anything like a cult. “He was too independent to get taken in by something like that,” Casterline says.

Maybe Robert Lesslie was giving the old football player pain pills, then cut him off—that theory was floated by Norman, the legislator friend, who said he’d heard as much from law enforcement. Then he said none of that conjecture was true. “I was mistaken on that,” he says now.

Or maybe the doctor pissed off Phillip some other way, as people close to Adams have speculated, seemingly based on the fact that the doctor treated Alonzo for back problems in the late 1990s, and that the two families lived only a mile apart. But if Phillip and Robert knew each other, nobody, including authorities, has been able to confirm that. Plus: Jamey Dagenhart, Lesslie’s business manager at the urgent care clinic, says Phillip was never a patient. There’s no surveillance footage from the day of the shooting, he says, that places Phillip there.

Maybe it all leads back, inevitably, perhaps obviously, to CTE, the degenerative brain disease, often linked to concussions, that so often shows up in the brains of dead football players. As wounds go, CTE is relentless; it never heals. It can lead to anxiety and depression, or paranoid, delusional and psychotic behavior. Officially, Phillip was diagnosed with two severe concussions during his career, but those close to him believe he suffered many more that went unreported. “I know that he had concussion problems,” Alonzo says. “There’s no doubt now.” The York County coroner is working with the CTE Center at Boston University to examine Phillip’s brain. Results, though, are expected to take nine months to a year, even longer than usual given a backlog created by the pandemic.

Maybe ...

“You try to become the investigator,” Ashley says, “and come up with your own theory. But you’ll drive yourself crazy.”

Phillip and Ashley were together for the better part of a decade, from college (where they began dating as freshmen at South Carolina State) until the final season of his NFL career. “We had our disagreements,” she says, “but it never turned to violence. He never made me feel unsafe. He never threatened me. There was never any time me and P.J. felt in danger.”

Phillip had a thing for guns, but not in a way that scared Ashley. He’d go to the shooting range, maybe carry a firearm with him sometimes, but “never anything crazy.”

She says she never saw Phillip yell; he never tried to hit her or P.J. or anyone else. “Hell, no,” she says, laughing. The end of their relationship, as far as she could tell, didn’t coincide with some dark new phase of his life—it ended during the best season of his career. He was with the Falcons in 2015, close enough for his parents to attend his games. Women were throwing themselves at him. “Having the time of his life,” she says. “If anything, I was the one at home, going through it.”

Things took a turn, she says, after Atlanta decided not to re-sign him. He’d played his best season of football, and still he didn’t get what he wanted from the game. And just like that, Phillip seemed to lose interest. He was invited to work out for the Colts the next fall and missed his flight.

Off the field, he told Ashley that he wanted his family back, that he wished things were different. But “it was just too late,” she says. And that can be hell for a father, a fractured relationship with another parent diminishing a bond with a child. He’d been a good dad, Ashley says—“very hands on … very present;” handled diapers, helped with potty-training. He’d tell friends how he wanted more time with his son.

Ashley remembers Phillip’s mood darkening further about two years ago. Suddenly, “he wasn’t the nicest with words,” she says. Things got worse, she remembers, after she let P.J. start playing football. Phillip would miss his son’s calls and took longer to respond to texts. He was inconsistent about taking P.J. for his weekends.

Looking back, Ashley thinks that perhaps Phillip withdrew from P.J. for P.J.’s sake. Their son picks up on people’s moods and can be deeply affected—Phillip knew that. “He knew he wasn’t in a great place to be a father,” she says. “So instead of picking him up, he just communicated with him via FaceTime and text messages.”

Phillip would call Ashley, begging her to put their family back together, then say he hated her, then apologize and promise that no matter what, she and P.J. would be taken care of.

But the last couple of weeks were different. Better. “Our communication was O.K.,” Ashley says. “He was getting it. We hadn’t had a disagreement. Now that I look back on it, it’s like he might have been smoothing things out with me because he knew that in the past he might’ve been wrong, or a little too harsh. It was kind of like, I’m sorry, without saying those words.”

Ashley and P.J. were watching a Fast & Furious movie recently, and one of the characters was driving a car that resembled Phillip’s blue Pontiac Le Mans, with its black racing stripes. “That reminds me of my dad’s car,” P.J. said. Then he probed in the way that children do, asking questions about one thing that are really about something else. “Does he still have that car? Is he ever going to come back and drive it?”

“No, baby, he’s not,” Ashley said. “But, if you’re sad and you want to talk to him, or ask him questions, you can just do it. Talk out loud.”

Ashley has P.J. in therapy. When she first spoke with the therapist, she found herself asking the woman unimaginable questions. Like: Do you feel comfortable doing your job well with my son, even though that means helping care for the child of a man who killed children? Are you going to be able to treat him normally?

“My baby is just so innocent,” she says. “I don’t want him to have to live in his dad’s mistake. His shadow.

“He is not his dad.”

The iPad ran out of power the other day. When eventually Ashley turned it back on, all of P.J.’s old text conversations with Phillip had disappeared. “He was so upset,” Ashley says. She restarted it, and the first thing P.J. did was check his texts to see whether his messages were there.

They were.

Sometimes P.J. will ask Ashley to go visit his dad’s grave, but she’s not ready to take him back there. She’ll tell him to look at his photos and his text messages again. P.J. will say, “I actually want to see him again.”

“He doesn’t understand the forever part,” she says. “Somewhere in his mind, he feels like he’s going to come back. So that’s hard to explain.”

She reminds him that it’s O.K. to be sad, O.K. to be angry, just to tell her how he feels. Or the therapist. Or anybody else. Talking helps you to find the things that threaten your peace—then you need to clear those things out before they get their roots in too deep, like weeds in a garden.

Alonzo called Scott Casterline, Phillip’s agent, the morning of the shooting. But Casterline missed it. Alonzo left a voicemail, said he wanted to talk about Phillip.

“I’m just kicking myself,” Casterline says. “What could we have done differently?”

On some level, Phillip’s family knew he was hurting. They also felt like he was figuring things out. He’d spend hours alone, reading or watching documentaries in a recliner, writing in his notebooks. That was normal for him.

Inside, though, Alonzo knew: “He had all kinds of pain.” And it wasn’t just the ankle or the concussions. Phillip’s NFL career had been one long series of high-speed crashes, and his whole body hurt, especially his neck and his back. It was bad enough that he’d tried to get admitted to some pain clinics, tried to get help from the NFLPA.

Even still, those who were around him all say the same thing.

Casterline: “That’s not the Phillip Adams I know.”

Ashley: “Phillip never came off to me as, like, hurting people. Let alone children. I wouldn’t think twice about [dropping P.J. off with him].”

Sterling: “I think I would’ve known if he would’ve been acting differently. I’m not saying I’m all that, but I didn’t see it.”

Which is almost a cliché in a situation like this, right? They never see it coming. But the cliché is the point, too. Phillip didn’t let people know him. Not all of him. “He was really headstrong,” Casterline says. “Proud. Raised to not show pain, and just internalize it. I’m sure it ripped him up.”

When Phillip was with Ashley, even his parents and his agent would have to contact Ashley to reach him. “If he doesn’t want to talk, he doesn’t talk,” she says. “He was very private. And very distant.” Whatever weeds had taken root in his mind, whatever demon deer was working on his soul, he never told anyone.

“Maybe I should have pushed a little harder,” Ashley says.

Alonzo: “We had no idea it was that serious. We probably never knew what he was going through as a person. He was so quiet.”

Alonzo has been visiting the house almost every day, even if that means just checking on the contractors, as though he derives some healing, or at least some comfort, from being there. Phillip’s cars are still parked in the backyard, a matte-black Camaro and the blue Le Mans with the racing stripes. Plus the four-wheeler he drove to the Lesslies’ home, now covered by a tarp.

Clearing out Phillip’s room one day, Alonzo found one of the first football jerseys his son ever wore, around when he was P.J.’s age, back when father started teaching son how to play the game. And God, how Phillip loved it. He never stopped asking questions about how to get better.

Alonzo gave the jersey to P.J., and the boy lit up. “My daddy’s jersey! My daddy’s jersey!”

He wonders whether that wasn’t a mistake. “Now,” he says, “I’d tell parents: Be careful letting your kids start playing football so young.”

It’s hard not to get caught up in trying to answer every question, in making some sense of it all, but it’s even harder to accept that this just might never make sense. The sheriff’s department hasn’t commented on Phillip Adams’s case in almost two months now. “They won’t tell us nothing,” Alonzo says.

While he waits, he continues working his way through his son’s things. “I’m digging,” he says. He’s found paperwork indicating that Phillip in fact tried filing with the NFL for disability benefits. “He was trying to get help for some of the things he was dealing with. We knew he was working on that, but we didn’t know how bad it was. Because kids don’t talk to you about how bad it is. … I can see the kind of hoops he had to jump through, because we are having to jump through those same hoops.”

On April 20, Alonzo requested his son’s medical and disability records from the NFLPA. He says he was told that he’d have them in two weeks—then, two weeks later, an NFLPA rep told Alonzo that he first had to provide Phillip’s official death certificate ... which Alonzo learned the coroner can’t release until an autopsy and toxicology reports are complete. Which is taking some time. Alonzo, meanwhile, has been able to get a temporary certificate from the coroner, but it’s not clear whether that will satisfy the NFLPA (which did not respond to inquiries from Sports Illustrated). He doesn’t anticipate it will. “That’s about what you expect from the league,” he says.

Navigating the more tedious aspects of life after any death—the arrangements, the paperwork, the almost clerical organizing of what someone else left behind—takes time. It hurts. A situation like this is multiples of that.

At the same time, Phyllis is starting to see a therapist, and Alonzo keeps working through his feelings with everyone in his family. “I tell them: ‘Talk about it,’ ” he says. “Don’t not talk about it. It’s important to lay it out there.”

Alonzo and Phyllis talk to one another plenty, and in doing so it becomes clear: “She don’t want to go back [to the house],” Alonzo says.

Sometimes you put something back together, you try to pick up the pieces, but it’ll never be what it was before. Sometimes the deer ravage your garden, or the weeds take over, and all you can do is accept all that is lost.

In fighting that, Alonzo is breaking down. A new rash appeared on his skin—something he’s never seen before. And there’s still the ankle. “Keeping me slowing down a little bit,” he says. “But it’s O.K.”

Alonzo and Phyllis start moving things into storage. They make plans to stay with family for a little while and do something they never thought they’d have to do again. They’re looking for a new home.

“The unknown is the scariest part,” Ashley says. The whole thing is “just so much on so many people’s minds.”

One afternoon, P.J. runs and plays on the patio outside the rear of the lobby at his grandparents’ hotel, dragging around metal chairs and racing other kids who show up because their moms need a smoke. He’s making moves around the inanimate obstacles he’s set up, holding his arm like he’s carrying an invisible football.

“With normal death,” Ashley says, “people bury their loved ones—family in town, coworkers, whatever. And everybody goes back to their normal life in a week or two. But us, it’s ongoing. … Hopefully we will get some clarity, some closure, and everyone can start healing. Because it’s gonna be a long journey. No one that I know is healing. There’s no way for us to begin to heal, because you just don’t know.”

You don’t know what you don’t know about a person. You don’t know the last time your son will talk with his father. You don’t know how long your kid will be innocent and happy, just juking around chairs. You don’t know when some goddamn deer will turn your garden into one big f---ed up situation.

“I just think about the good times,” Ashley says.

You don’t want to defend a murderer—but you also don’t want a boy to believe that his daddy was all bad, because what’s that going to make him believe about himself?

Ashley opens up a video on her phone and P.J. comes over to watch. On the screen, Phillip is working receiver routes with P.J. and some other kids, and P.J. makes a sweet move to shake his defender and make the catch. “That’s the move my daddy gave me,” he says. He grins, watching himself. “Jukin’. I be, I be, I be jukin’.”

On the day before the shooting, P.J. wanted to FaceTime his daddy from Miami. Ashley was nervous as P.J. made the call on his iPad, hoping Phillip would answer.

He did.

Now, as P.J. sits quietly in her lap, Ashley says, “I’m grateful. I’m glad they actually talked.”

They spoke for 10 minutes. Phillip asked his son whether he’d been reading, and P.J. told him what he’d been eating, where they’d been, and especially where they were about to go. They were headed to the zoo. He was going to feed some parrots. When they bid goodbye, Phillip said, “All right, I love you, buddy. I’ll talk to you later.”

• 'This Should Be the Biggest Scandal In Sports'

• FaZe Clan Is Changing the Game

• A Journalist Died Over a Soccer Feud. ... Or Was There a More Sinister State Plot Involved?