The match-day atmosphere is raucous and little separates club from community at this third-division soccer team.

America is full of sports wonders, but they aren't always easy to find. The October 2021 issue of Sports Illustrated spotlights Hidden Gems across the country, from a Wimbledon replica in heartland farm country to a custom-built sandlot baseball field in Texas. As it turns out, there's nothing like feeling the magic of sports in places you'd least expect.

Friendly the Bear was discovered, abandoned, in a dumpster. He was perfect.

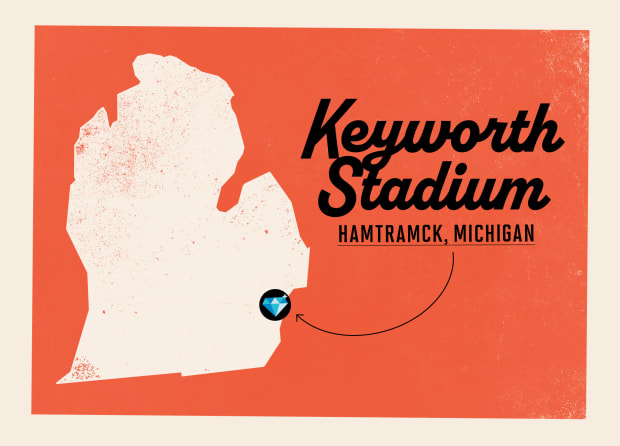

Salvaged almost a decade ago by a friend of Detroit City Football Club’s founders, the unwanted costume has found new life at 7,933-seat Keyworth Stadium, a Depression-era urban venue that also required resurrection. Friendly is now ironically iconic. He humors thousands at games, and he’s honored with a black velvet painting inside the bar and restaurant that anchors DCFC’s clubhouse.

“We were looking for halftime entertainment and we decided to use Friendly one game, and it kind of caught on,” DCFC cofounder and CEO Sean Mann recalls. “We just loved the idea that it was a dumpster bear. It’s not pleasant [to wear], but it’s not much worse than any other mascot.”

Friendly is the ideal avatar for an irreverent and industrious third-division soccer team that hustles just to break even in a major league city. And he’s a poignant personification of that city, which many once left for dead.

The Detroit City match-day ritual begins at the Fowling Warehouse, a former axel factory that’s been converted into a massive sports bar with 30 lanes for “fowling,” a game where you heave a football at bowling pins. From there, DCFC’s Northern Guard Supporters march half a mile, flags waving and megaphones blaring, down the adjacent hill and through the narrow streets of Hamtramck, an industrial enclave inside Detroit, and turn up Roosevelt Street to Keyworth. Kids wave from windows and porches. Nobody has ever complained about the commotion, Mann says, even with the amplified profanity. There hadn’t been this sort of clamor around here for a while.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Keyworth Stadium is reminiscent of those old English grounds that rise up suddenly from a dense, residential neighborhood. Opened in 1936 by FDR, it was the first Works Progress Administration project in Michigan. Pope John Paul II celebrated mass there in ’87, which would’ve been a big deal in Hamtramck, an area that was mostly Polish for much of the 20th century. Now it’s heavily Yemeni and Bengali.

When Detroit City launched in 2012 as an amateur team—the club didn’t go pro until ’20—it played games at Cass Tech, an inner-city high school. But the upstart side quickly outgrew it and turned to Keyworth. Starting in ’15, in partnership with Hamtramck and funded by more than $750,000 raised by nearly 500 supporters, DCFC rebuilt the mostly condemned stadium, from the plumbing and electrical wiring to the bleachers, which were installed and painted by dozens of fans.

Yard lines on the turf field are a sobering reminder of soccer’s place in the local sports hierarchy. Otherwise, Keyworth is very much Detroit City’s home. During games, it pulses with sound and smoke. (Smoke Delay IPA is the club’s branded beer.) Northern Guard members occupy most of the east stand, and matches are played to the rhythm of their chants and drums. Trains gliding by on the tracks behind the south goal blow their whistles in support. More than 6,000 fans attended DCFC’s season opener in early August.

“It goes from being like a lot of buildings in Detroit, which were abandoned and run down,” says DCFC’s coach and GM Trevor James. “Suddenly it’s alive.”

When Detroit hosted Super Bowl XL in 2006, the city erected temporary façades and storefronts to hide the emptiness downtown. From ’00 to ’10, Motown’s population—in 1950, the fifth-largest in the U.S.—fell by 25%, to about 713,000. Detroit’s decline, due in large part to the auto industry’s downturn, became part of its brand. But its gradual resurgence helps define Detroit City’s.

Formed by five friends who pitched in $2,200 each, DCFC has become the darling of U.S. minor league soccer while playing an outsized role in breathing life back into the Motor City. Despite trophies (such as the 2020–21 National Independent Soccer Association title) and an over-the-air TV deal in five Michigan markets, Detroit City is often overlooked by local media. But with the help of fans who’ve become part owners, the club is building—and rebuilding—something profound.

Detroit City now fields two men’s teams—including the third-division pro squad—and two women’s sides, which are targeted for additional investment. There’s a youth program. There’s the Detroit City Futbol League, a coed adult circuit that predates the senior team and includes volunteering incentives that can impact the standings. The 11-year-old league and its itinerant postgame parties have forged ties not only between neighborhoods but also among investors, sponsors and local officials. Those relationships have created more DCFC fans (and even marriages).

“We didn’t build anything new,” says Jackie Carline, who helps conduct the match-day sound and fury as a Northern Guard capo. “We took things that were there, that maybe needed to be cleaned up and restored a bit, and brought them back to life.”

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Bordering a cemetery and a high school two miles northeast of downtown, the 75,000-square foot Detroit City Fieldhouse is one of those places. The former Red Wings facility features two artificial pitches, a locker room, training room, gym, players’ lounge, offices and a public restaurant. Pre-pandemic, fans mingled with players and owners at happy hours and watch parties while youth teams, the DCFL or the area’s Mexican men’s league used the fields. Massive banners, or tifo, created by the Northern Guard ring the walls. Between game days, this home base is where DCFC congregates—and opens its doors. In October, for example, the Fieldhouse will host an expo by members of the Metro-Detroit Black Business Alliance.

It’s a setup that’s rare in the U.S., if not unique. For many, Detroit City has evolved into a lifestyle or calling. The core supporters are progressive and dedicated idealists who’ve found meaning in the discarded and abandoned. They’ve united to create a true club that’s as colorful and authentic an expression of local pride as you’ll find in U.S. sports.

It reminds James of soccer’s foundation. He’s from England, where football clubs created more than a century ago by friends and colleagues developed organically into behemoths. Their supporters believe that even teams like Manchester United (started by railroad workers in 1878) should remain civic assets that answer to fans first. The power of that idea was clear in April, when protests brought the ill-conceived European Super League to a humiliating halt. Most U.S. sports teams are created out of thin air by a rich man signing a check. DCFC was assembled, piece by piece, by a community.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Last year Carline and some 2,700 fellow supporters, including Detroit’s own Iggy Pop, raised $1.5 million to help steer DCFC through the pandemic. They now own 10% of the club. It’s easy to cringe when fans refer to their favorite team as “we,” but it’s reality in Detroit.

“That’s the essence of DCFC, whether it’s working to rebuild Keyworth or the effort they put into the match-day atmosphere,” Mann says. “It’s their sweat equity that defines this club.”

And they protect what’s genuinely theirs. A banner at Keyworth reads CLUB > LEAGUE. When NBA owners Dan Gilbert and Tom Gores considered bringing an MLS expansion team to Detroit in 2016, the Northern Guard resisted. It sold FCK MLS T-shirts, wrote letters protesting potential trademarks, and even bought domain names corresponding to the ill-fated bid’s slogans and redirected them to the DCFC website. The pushback prompted MLS commissioner Don Garber to call Mann and ask why DCFC fans loathed his league.

“I don’t think our fans hate MLS,” Mann says. “But they hate the idea that the club they built could be taken away from them. We’ve navigated those conversations and stayed true to who we were and built on that. That’s not just idealism. That’s how we’ve created something that stands out.”

More Hidden Gems:

• Welcome to the Lone Star State's Sandlot Revolution

• Iowa's Court of Dreams is More Than a Wimbledon Replica

• Inside Kentucky's Storied Lakeside Swim Club