Pak started a golfing boom in her home country when she burst onto the scene by winning two majors in 1998. And now the women she inspired (and who she still mentors) are dominating the sport.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. Come back all week for more Where Are They Now? stories.

In late April, for the first time in its 72-year history, the LPGA held consecutive tournaments in Los Angeles, home of the United States’ largest Korean population. This twin bill opened with the DIO Implant LA Open at Wilshire Country Club, where a South Korean dental company served as title sponsor and a food truck near the clubhouse served up Korean fried chicken. After the pro-am—during which her playing group included visitors from as far away as Seoul—seven-time major champion Inbee Park recounted to reporters her surprise at having been recognized by a Korean exterminator who was treating the place she was renting during the event, less than three miles away in Koreatown.

One week later, shouts of the Korean rally cry Hwaiting! (essentially: let’s go!) filled the breezy coastal air as Jin Young Ko made the turn in her third round at the Palos Verdes Championship, tailed by a gallery ranging in age from visor-wearing halmeonis (grandmas) to a pair of young girls who filled dead time by practicing their own swings with invisible clubs. Later, coming off the 18th green, the world No. 1 debriefed with a South Korean television station while a camera-chasing boy frantically flapped the country’s red, blue, black and white flag in the background.

“Palos Verdes was more in the countryside compared to Wilshire, so I was surprised that there were so many Koreans,” Ko says. “I heard a lot of Korean while I was playing. It felt as if I was back in Korea.”

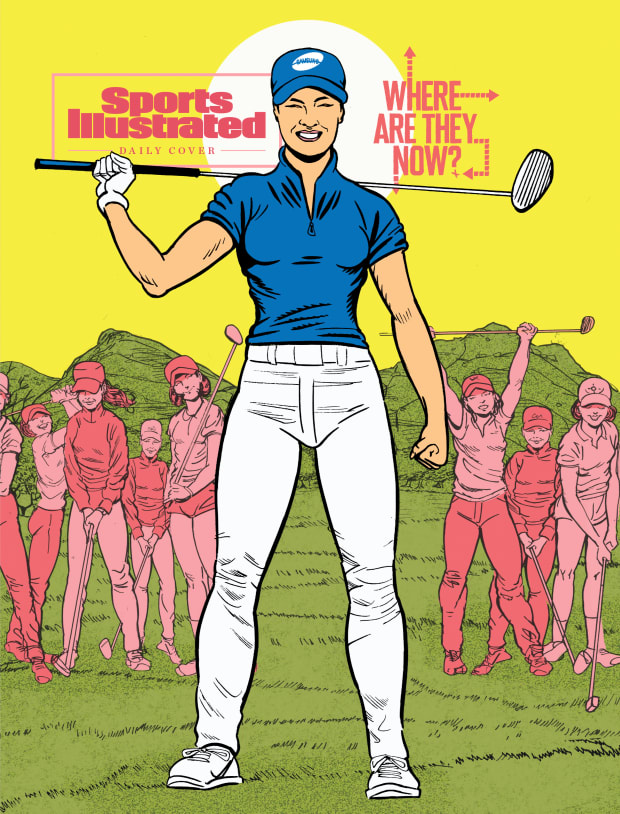

Illustration by Felipe Flores

No matter the location these days, such scenes are increasingly par for the sport’s course. Consider: Since 2012, Ko and 12 of her compatriots have combined to claim more than two-fifths of all LPGA majors (21 out of 51); in that same span South Korea has also produced six out of nine tour rookies of the year, most recently ’19 winner Jeongeun Lee6, who uses the digit in her official title as a way to distinguish herself from the five other Jeongeun Lees who preceded her in the professional ranks. All told, as of the end of June, five of the top 13 and 30 of the planet’s top 100 female golfers represented South Korea, more than any other nation. And: That is without counting expatriates like No. 5 Lydia Ko, raised in New Zealand after moving from Seoul when she was young, or foreign-born daughters of Korean immigrants such as No. 2 Minjee Lee, the Australian winner of May’s U.S. Women’s Open.

Now consider that, just a quarter century ago, there were zero card-carrying Korean players on the LPGA tour.

How did we get here? How did a barren landscape blossom so fast? How, long before the age of bulgogi and BTS, skincare sheet masks and Squid Game, did another seismic cultural wave from a nation the size of Indiana crash onto U.S. shores and flood golf’s highest level? Systemic factors no doubt chipped in, namely how corporate sponsorship teamed up with South Korea’s robust domestic tour to make golf an attractive option for young girls. But many cart paths lead back to a lone trailblazer who burst into the LPGA with back-to-back majors as a 20-year-old rookie in 1998, lifting up a society reeling from economic ruin and giving way to a generation of golfing successors—all of whom first took up the sport as a result of her success, many of whom still directly benefit from her tutelage—dubbed by South Korean media as the Seri Kids.

“A lot of people [are] curious why Korean players are so good,” says one such spawn, two-time major winner Soyeon Ryu. “One of the biggest things is we always had a really good role model. Seri opened up the door.”

Adds Jin Young Ko, another Kid: “Back then, in Korea, golf wasn’t that popular. She gave dreams for many Koreans to go to America, to play and also win. Thanks to Seri, Korean women’s golf could grow.”

Says a third, In Gee Chun, winner of last month’s Women’s PGA Championship: “It’s the Seri Kids story: They watch her on TV, they see how she played, they get inspired to be a great golfer like Seri Pak.”

Darren Carroll/Sports Illustrated

Golf came to the land now known as South Korea around the turn of the 20th century, introduced by foreign missionaries and maritime workers amid an era of Japanese occupation. “However, golf courses completely disappeared from the Korean Peninsula over the course of the Pacific War and the Korean War after the liberation of Korea from Japan,” recounts an April 2020 article in the Asian Journal of Sport History & Culture. “Korean golfers who survived the Japanese colonial era began to rebuild the golf courses, thereby creating the cornerstone of what has today become a global golf powerhouse.”

Equality on the links, however, took longer to attain. “In the 1970s, a woman’s place on South Korea’s golf courses was as a caddie,” Karen Crouse wrote in The New York Times. But that paradigm shifted when the Korea Professional Golf Association debuted its women’s division in ’78 with a single tournament and just eight card-carrying members, among them a former caddy, Ok-Hee Ku, who later became the first Korean player to win an LPGA or PGA event when she prevailed at the former’s ’88 Standard Register Turquoise Classic in Phoenix by a single stroke. (It would be another decade-plus before the first Korean man—K.J. Choi in 2002—would follow suit on the PGA Tour.)

Three years after Ku set the bar, some 100 miles south of Seoul in the smaller city of Daejeon, a middle-schooler named Seri Pak began seriously playing under the guidance of her father, the owner of a construction company and a scratch golfer. The second of Jun Chul Pak’s three daughters endured a strict training regimen, running stairs in the family’s 15-story apartment building and practicing chip shot every day at dusk … in the dead of winter … on the outskirts of a local cemetery. (The latter supposedly doubled as a mental toughness exercise—teenage Seri was terrified of graveyards.)

After turning pro at 18, success came quickly: Pak won six events in her first two KLPGA seasons and signed a $10 million, 10-year sponsorship with Samsung that bankrolled her eventual move to Orlando and hiring of famous swing coach David Leadbetter. “Playing the LPGA was one of my first big dreams,” Pak says now. “I was trying to be [the] world’s best golfer.” But not even she could have forecasted how fast she would get there, winning the LPGA Championship at Delaware’s DuPont Country Club by three strokes as a rookie in May 1998. Then, 50 days later, as television sets across Korea glowed long past midnight local time, Pak prevailed at the U.S. Women’s Open at Wisconsin’s Blackwolf Run, too; in what became an instantly iconic image in her homeland, she peeled off her shoes and socks before wading into a water hazard and striking a perfect second shot from the rough on the 18th hole of a 20-hole playoff against amateur Jenny Chuasiriporn.

Illustration by Felipe Flores

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

As she reflects on her early days in the U.S., though, Pak remembers not just deep fulfillment but vast isolation. “First couple months, everything is lonely,” she says. “I was not close to any players. I never used the locker room, because they spoke English and I didn’t know [how]. Only parking lot, to the course, back to the car, back to the hotel, back to the course in the morning. Just lonely, lonely, lonely.” A single thought kept her going: “The one thing on my mind [was] my dream to be great,” Pak says.

In a testament to how thoroughly she ticked off this box, Pak was hardly alone for long: By 2007 the number of Korean players who had joined her in jumping from the KLPGA to the LPGA had swelled to more than 40, with three (Grace Park, Birdie Kim and Jeong Jang) even winning majors. “Very proud of myself,” Pak recalls. “Very happy to see that happening.” The following summer marked another seminal moment when the first Seri Kids announced their arrival—and in fitting fashion, too, as 19-year-old Inbee Park surpassed Pak as the youngest U.S. Open champion ever.

“We were going through a tough time in the country,” Park says, referring to the ’97–98 Asian financial crisis that put more than 1.5 million out of work in South Korea alone; led to International Monetary Fund bailouts for the country and others; and left little room for expensive leisurely activities like golf. “She gave a lot of people hope that you can do it. After Seri won, everyone wanted to take their daughter out to golf.”

But the weight of expectations pushed Pak into what she describes as a two-and-a-half-year “slump,” punctuated by her first missed cut at a major, at the 2005 LPGA Championship. “All of a sudden it just happened. I realize this is burnout.” Early retirement beckoned. “I thought almost, ‘This is it, this is done, I give up,’” Pak says. But in the end she resisted, rebounding to not only survive the cut at the next LPGA championship, in June ’06, but to gut out her fifth and ultimately final major with a birdie on the first hole of a sudden-death playoff against Karrie Webb. The next year she entered the World Golf Hall of Fame at 29, eclipsing Webb as the youngest woman to ever be enshrined. “The biggest thing I learned was to make the right balance,” Pak says. “It doesn’t matter if you winning or not. Just that you’re healthy and enjoying playing.”

It is a message that Pak would seek to pass along as she entered the back nine of her career endowed with a new purpose—a new dream—thanks to her golfing offspring. “[First hearing about the] Seri Kids, it was a lot of pressure,” she says. “I don’t know how to lead the young players that come from Korea [because] I’m still learning myself. But after a couple years I realized: I know what to do, I know how to do it, and if I can stand up a little stronger for them, I should try to help.”

ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP/Getty Images

After the 1998 U.S. Open, Pak returned home to a packed schedule of interviews, meet-and-greet events and welcome-home celebrations, including a parade arranged by the South Korean president. Equal fervor awaited her next KLPGA appearance, in Seoul, where among thousands in attendance was a 10-year-old named Na Yeon Choi, whose family made the 10-minute drive from home to witness the spectacle.

“I was holding my dad’s hand, trying to walk all 18,” Choi says. “It was amazing. So many people cheering for Seri. If I think about that moment, it still gives me some goose bumps.”

Having played golf herself for about a year by that point, Choi, now 34, saw the effect up close at her local club. “When I started, nobody played golf in Korea,” she says. “Very expensive, people think that’s not even sports, because it's just walking with a stick. After Seri won, so many people started golf. It was only four or five players at my age, then six months later it was over 100.”

As the Kids grew up and started sharing tee boxes with their namesake, getting over their idolatry often proved tough. “Korean culture, you got to respect the elder, so it was really hard for me to approach her, because she’s a legend,” says Haeji Kang, 31, the world’s No. 162–ranked player. “I think I could barely talk.” Adds Chun, 27, recalling a dinner of Korean barbecue that Pak cooked for her and other Korean players in Orlando when Chun was an LPGA rookie in 2015, “I was happy to go to her house. It was really pretty. But I was really nervous to spend time with Seri.”

Pak remembers this distance. “They try to say hi to me, first time, it’s like they don’t know how,” she says. “They’re so cute, though.” But she slowly chipped away, in part by filling others’ bellies and in part by opening up her soul. “When I first started on tour, I told Seri that she was definitely a lot of inspiration,” Ryu says. “She was like, ‘Omigosh, I feel so sorry, this is such a tough job, I’m sorry for dragging you into a tough job.’”

More than any advice about stances or swing paths, Pak preaches the power of getting away from the game to her Kids—a far cry from her father’s famously intense methods. “What Seri had said was, while playing golf, it’s important to have [your] own hobby outside of golf, so you can become a true, happy golfer,” Jin Young Ko says. Adds Chun, recounting a common message that she receives from Pak on the popular Korean app KakaoTalk: “She says, ‘In Gee, you need a good balance: This is how you keep playing golf longer.”

For Pak, the point is to help the next generation avoid the pitfalls that marked her prime. “I know they do their best; they work hard,” she says. “I want them to know, ‘You’re do great, enjoy your life.’ Not go through this black, dark hell.”

Hampered by shoulder issues, Pak played her final Stateside event at the 2016 U.S. Women’s Open, six years after her last of 25 LPGA wins, wrapping one of her playing partners in a tight embrace at the end. “I didn’t know I was going to cry, but I did when she hugged me,” Ryu says. “That was really weird. For example, Superman’s still on TV. Iron Man’s still on TV. But Seri’s not going to be on TV anymore, at least as a golfer. It felt like I was going to lose a hero.”

But Pak got a shotgun start on life after golf when she served in a manager-coach role for the Korean national team at the 2016 Summer Olympics. There her original Kid protégé, Park, defied both a nagging thumb injury and sky-high expectations—in large part thanks to the prevailing assumption back home that a Pak-coached delegation could never fail—to win by five strokes, becoming the first women’s golf gold medalist in 100 years.

Asked what she remembers most from the Olympics, Pak points to quieter moments with her four-woman squad, such as the nightly dinners that she cooked at her rental house to bring a taste of home to Rio. (Sample menu items included kimchi jjigae, or kimchi stew; and budae jjigae, traditionally a spicy-brothed hodgepodge of Spam, hot dogs, baked beans and other canned foods culled from U.S. military bases in a period of widespread poverty following the Korean War.) Then there were the conversations over Earl Grey tea that followed—about golf, yes, but also balance.

“Just being together,” Pak says. “Just being with Seri Kids, sharing it. That is [the] moment I said, ‘I’m [the] luckiest person ever.’ That is some of the proudest I have ever been in my life.”

Yong Teck Lim/Getty Images

Kyoung-yim Kim met Seri Pak way back in the early 1990s, when Pak was still an amateur player. Kim was caddying for her sister at a KLPGA tournament in Pak’s hometown, and both were standing in the clubhouse locker room. Some two decades later, having all but abandoned her dream of becoming a pro golfer herself, Kim spun her lasting love for the game into a 352-page doctoral dissertation analyzing the cultural factors behind the era of the Seri Kids, and how U.S. and Korean media covered them. (Title: “Producing Korean Women Golfers on the LPGA Tour: Representing Gender, Race, Nation and Sport in a Transnational Context”)

Now an associate professor of sociology and women’s and gender studies at Boston College, Kim says that both sides missed the green in emphasizing individual exceptionalism to explain the success of South Korean players—that somehow they were biologically predetermined to be dope at golf—over increasingly corporatized support for the whole sport. Even then, though, it all funnels back to the same single name: “Before Seri, women’s golf and the corporations who are sponsoring women’s golf were gendered products, like kitchen or groceries or fashion,” Kim says. “But after Seri, the sponsorship for women’s golf changed to automobile, bank, and information technology, and many more. Expanding the horizon of sponsorship—introducing women’s golf as a stable and glamorous career—that was Seri’s major impact.”

There is no shortage of ways to measure Pak’s legacy through a commercialized lens. “If a business plan existed for the LPGA five years ago, I don’t think that Korea would necessarily have been in it,” then commissioner Ty Votaw declared in 2003, four years after the first dedicated golf channel launched in South Korea in the wake of Pak’s landmark U.S. Open win, and 11 years before the LPGA established its first Asia office, in Seoul. The ripple effect is even starker today at the domestic level, where the KLPGA regularly offers bigger prize purses, attracts bigger crowds and secures higher broadcast ratings than its male KPGA counterparts.

But to focus on the money and the masses is to miss how Pak has personally impacted her progeny, starting with this: None of them lack companionship on the road. “I’m sure it was a lot more difficult for Seri, because she didn’t have much Koreans around her,” Kang says. “Now we have a lot of Korean friends.” A few of them, including Chun and world No. 11 Sei Young Kim, own houses in the same Dallas neighborhood, gathering for practice rounds and dinners each offseason.

Even amid the bustle of competition, kinship blooms: Ryu recounts her enjoyment swapping “research” with fellow players about the most authentic Korean restaurants in each tournament city. “Not just about the food: Anytime we have a good Korean show, we’re able to talk about it,” Ryu says. “A lot of [non-Korean pros] are curious, ‘What are you guys talking about? We just try not to talk about golfing, because that’s the way we make balance between the golf life and our life.”

Despite Ryu’s fears that she would disappear from television, Pak remains as relevant a symbol in retirement as any fictional superhero, lending her legend’s perspective to the analyst’s booth at KLPGA broadcasts since 2017. She is also a frequent face on wholesome Korean reality-variety programming: Past credits include a hosting gig for Seri Money Club (in which Pak teaches golf to experts in other fields for charity); a recurring role on Sporty Sisters (in which Pak and fellow retired female athletes hang out and try new activities together); and four episodes of the Survivor-like competition Law of the Jungle (in which Pak and other celebrities were stranded on the Cook Islands for five days).

But Pak’s busy schedule hasn’t prevented her from keeping an eye on her Kids. She still extends meal invitations to KLPGA players after tournaments she works, sometimes even grilling up bulgogi and samgyeopsal (pork belly) for small groups at her Seoul condo. And while South Korea failed to repeat at last summer’s rescheduled 2020 Olympics—Jin Young Ko and Sei Young Kim finished highest, tied for ninth—Pak relished the chance to reprise her coaching role, delivering cooling spray to players on the course in the thick Tokyo heat, buying up fruit and other desserts from local convenience stores for their traditional postdinner gatherings.

“That’s how we got closer,” Ko, 26, says. “Because of the age gap I didn’t think it could be possible. But she has been very supportive.”

At the same time, Pak’s ultimate dream is to open a specialized academy for promising young golfers, one that houses practice ranges, training facilities, classrooms and dormitories all in a centralized location. “We don’t have enough sports centers in Korea,” Pak says, adding that she and a business partner have begun scouting sites outside Seoul and forming their fundraising plan. “I want Seri Kids to go through nice conditions, then [pass it on] to another kid and make their dreams come true.”

So a generation of Seri Grandkids, then?

“Yeah,” Pak says. “Hope so.”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• John Amaechi: ‘You Want Gay People to Come Out: Make It So It’s Not S----y’

• Steffi Graf Is Still Too Famous For Steffi Graf

• The GOAT Abides: Gary Smith, the Sportswriter in Repose