It’s tough to be excited about MLB these days—and not just because of the lockout.

Good morning, I’m Dan Gartland, and I don’t care if you think I’m too anti-owner.

If you're reading this on SI.com, you can sign up to get this free newsletter in your inbox each weekday at SI.com/newsletters.

Sorry, this is going to be a bummer

With the benefit of hindsight, I feel pretty stupid for even partially believing MLB ownership’s transparent PR tactic of saying it was nearing a deal with the union.

As Giants pitcher Alex Wood put it, “MLB has pumped to the media last night & today that there’s momentum toward a deal. Now saying the players’ tone has changed. So if a deal isn’t done today it’s our fault. This isn’t a coincidence. We’ve had the same tone all along. We just want a fair deal/to play ball.”

Shortly after Wood’s tweet, the league announced that it had presented the union with its “best and final offer.” It wasn’t much different from the offer presented to the players at the end of Monday’s marathon negotiations, so they rejected it and MLB followed through on its threat to cancel games in the absence of a deal.

The first two series of the season have already been canceled. If MLB remains firm in insisting that there be four weeks of spring training before the regular season begins, you’re looking at losing six games for every additional week that the lockout drags on. The Athletic’s Evan Drellich reported on Monday that the league was willing to skip as much as a month’s worth of games.

A messy labor battle that drains baseball fans of any excitement they might have about their favorite teams and players is the last thing MLB needed. The league was already facing all sorts of serious issues before the lockout:

- An analytics-driven focus has hitters pursuing a three-true-outcomes approach (walk, strikeout or home run) at the plate.

- The prevalence of defensive shifts has reduced action on the field.

- A hidebound culture that chastised players for violating perceived unwritten rules dampened the joy of the game. (Although, that appears to be changing.)

- Cheating scandals related to sticky stuff and sign stealing shook the integrity of the game.

- MLB’s decision to strip 42 minor league teams of their big league affiliation made it harder for fans outside major cities to build a connection with the game.

- An earlier labor dispute led to a sham of a 60-game regular season in 2020.

- A former team employee was just convicted of providing drugs to a player, leading to his fatal overdose, in a trial that raised further questions about drug use in the game.

Now, add the lockout on top of all that. Why should anyone be excited to be a baseball fan right now? The 2022 season was an opportunity for MLB to make a big splash. For the first time since ’19, every team in the league would be allowed to a full stadium for Opening Day. This could have been a chance to remind people that there isn’t a better way to spend a sunny day than outside at a baseball park. Instead, it’s a reminder that MLB owners care more about lining their pockets than the health of the game fans love.

Baseball doesn’t have any owners left whose sole (or even primary) motivation is winning. In fact, everything owners have done in recent years indicates that they don’t care about baseball at all. They considered skipping the entire 2020 season because they couldn’t get the players to agree to steep pay cuts. They slashed the minor leagues to save a few bucks. Their boss, commissioner Rob Manfred, faced harsh blowback from players after he called the World Series trophy a “piece of metal.”

For the majority of owners, a baseball team is nothing more than an asset. It might as well be a chain of car dealerships,a tech company or a collection of commercial real estate. (Hey, two teams—the Blue Jays and Braves—are owned by massive corporations.) But unlike most businesses, it’s an asset that prints money year after year and steadily increases in value. Owning a piece of a legalized monopoly is a good racket if you can get into it. It’s an even better racket if you can sell your piece and get out of it with more money than you started with. Owners don’t have to be concerned with baseball’s standing in American culture 40 or 50 years from now because they can always sell their team when they sense the tide turning. Fans are in this for the long haul, though, and the owners are making it tough to enjoy the game we love.

The best of Sports Illustrated

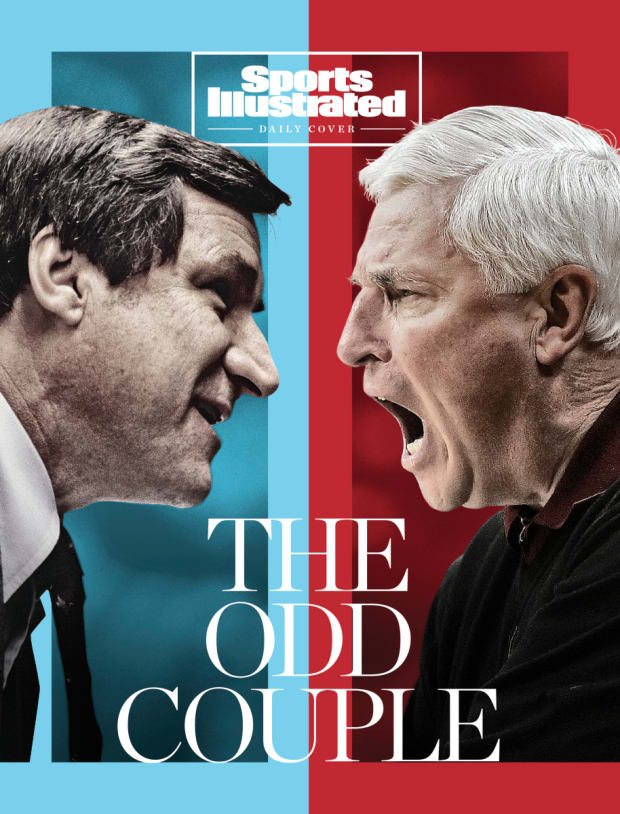

Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty Images (Smith); Streeter Lecka/Getty Images (Knight)

In today’s Daily Cover, Jon Wertheim explores the unlikely friendship between Dean Smith and Bob Knight. … Chris Herring wrote a very well-timed story about Ja Morant and the one move he’s using to torture defenders. … In his latest Bracket Watch, Kevin Sweeney weighs whether Gonzaga’s spot as a No. 1 seed is secure. … Avi Creditor takes a look at who the USMNT might call up for the final World Cup qualifying window. What does JJ Redick have to say about playing with Ben Simmons and Joel Embiid? He checked in with John Gonzalez on today’s SI Weekly podcast.

Around the Sports World

ESPN reportedly wants to bring in Derek Jeter to work as an analyst. … Former UFC champion Cain Velasquez was arrested on suspicion of attempted murder for reportedly trying to shoot a man accused of abusing a family member, hitting the man's stepfather instead. … The Wisconsin men clinched a share of the Big Ten regular season title with a last-second shot against Purdue. … Bruce Arians ruled out the idea of trading Tom Brady if he wants to come out of retirement.

The top 5...

… lies Rob Manfred told yesterday:

5. “Our committee of Club representatives committed to the process, offered compromise after compromise, and hung in past the deadline to exhaust all efforts to reach an agreement.” (The league set the arbitrary deadline.)

4. “We also listened to our fans. The expanded playoffs would bring the excitement of meaningful September baseball and postseason baseball to fans in more of our markets.” (There’s no way a majority of fans support a postseason format that renders the regular season effectively meaningless.)

3. “I want to assure our fans that our failure to reach an agreement was not due to a lack of effort on the part of either party.” (Ownership made no effort to negotiate for 43 days after instituting the lockout.)

2. “The concerns of our fans are at the very top of our consideration list.” (You wouldn’t stall on negotiations to the point where a delay necessitated canceling games if your primary consideration was the fans.)

1. “The last five years have been very difficult for the league from a revenue perspective.” (In 2019, the last season before the pandemic, the league brought in a record $11 billion in revenue. Revenue over the last five years totalled $43 billion.)

SIQ

On this day in 1989, Mets outfielder Darryl Strawberry got in a physical altercation with a teammate on picture day at spring training in full view of a gaggle of media members. (There’s a video of the incident on YouTube that I’ll link to when I reveal the answer tomorrow.) Who was the teammate?

- Gary Carter

- Mookie Wilson

- Roger McDowell

- Keith Hernandez

Check tomorrow's newsletter for the answer.

Yesterday’s SIQ: Among replacement players who had not previously played in the majors before the 1994–95 MLB strike, who went on to have the longest big league career?

Answer: Ron Mahay, who played 15 seasons. He had been picked in the 18th round of the MLB draft by the Red Sox in 1991 and got called up from the minors to be a replacement player for spring training in ’95. He made his big league debut in May and played five games in center field before getting sent down to the minors. After being demoted, Mahay was converted to a pitcher and went on to play 14 years as a reliever.

Crossing the picket line to play in spring training in 1995 made replacement players ineligible to join the players union, but many of them enjoyed long careers in the big leagues, including Kevin Millar (12 seasons), Tom Martin (11), Matt Herges (11) and Damian Miller (11).

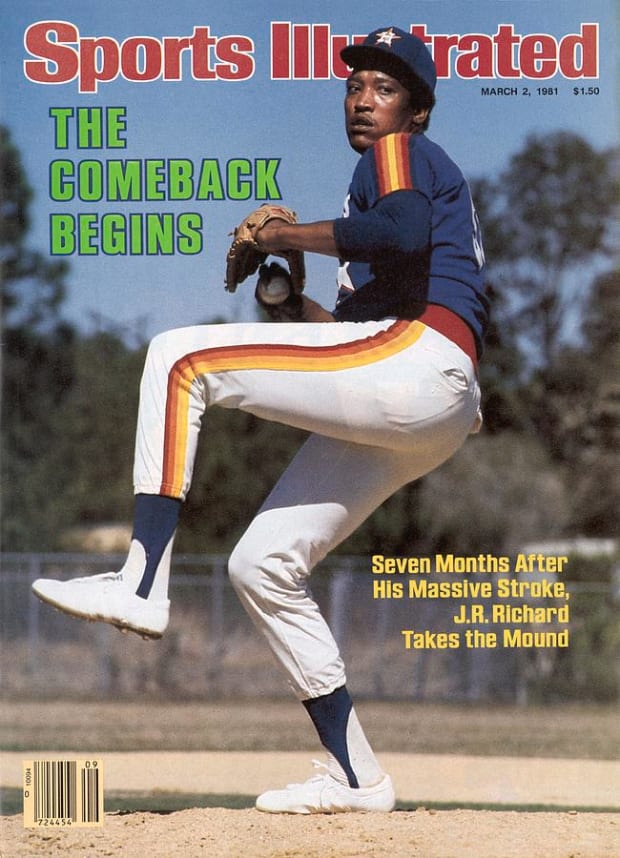

From the Vault: March 2, 1981

Astros ace J.R. Richard was one of the best pitchers in baseball in the late 1970s. In ’79, he led the majors with a 2.71 ERA and 313 strikeouts, enough to earn him a third-place Cy Young finish and place 19th in MVP voting. He was off to a great start in ’80, too, with a 1.90 ERA in 17 starts, but his season came to a sudden, tragic end on the morning of July 30, when he suffered a stroke on the field at the Astrodome while playing catch.

The stroke (and particularly the events leading up to it) is a fascinating story in its own right. William Nack wrote a cover story for the Aug. 18, 1980, issue of SI, detailing how Richard had complained for months about mysterious arm fatigue. With doctors unable to diagnose what was wrong with him, fans, media members and even teammates accused Richard of faking or embellishing the extent of his injury. The source of the fatigue was later revealed to be a blood clot, which led eventually to his stroke.

Nack visited Richard again at spring training in 1981 as the 30-year-old pitcher attempted a comeback, seven months after the stroke. Nack described how Richard had regained the strength in the left side of his body (which had been left “virtually paralyzed” by the stroke) and was speaking as he did before the incident. He was eager to make a comeback, made possible by an 18-hour surgery the previous October in which doctors removed a piece of artery from his abdomen and put it in his pitching shoulder to bypass the clotted, damaged piece of artery responsible for the stroke.

Nack’s story is optimistic, but Richard never managed to make it back to the majors. His comeback ended in 1983 after a series of rehab assignments. After retiring, Richard lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in a bad oil deal and a divorce. By ’93, he was homeless, living under a bridge in Houston, not far from the Astrodome. A short SI article from ’98 describes how Richard landed back on his feet, eventually becoming a minister at a Houston church. He died on Aug. 4, 2021, from complications of COVID-19. He was 71.

Check out more of SI's archives and historic images at vault.si.com.