How have college sports changed in the year since name, image and likeness laws disrupted the landscape?

Good morning, I’m Dan Gartland. I can’t believe it’s only been a year since the NCAA’s NIL policies went into effect.

In today’s SI:AM:

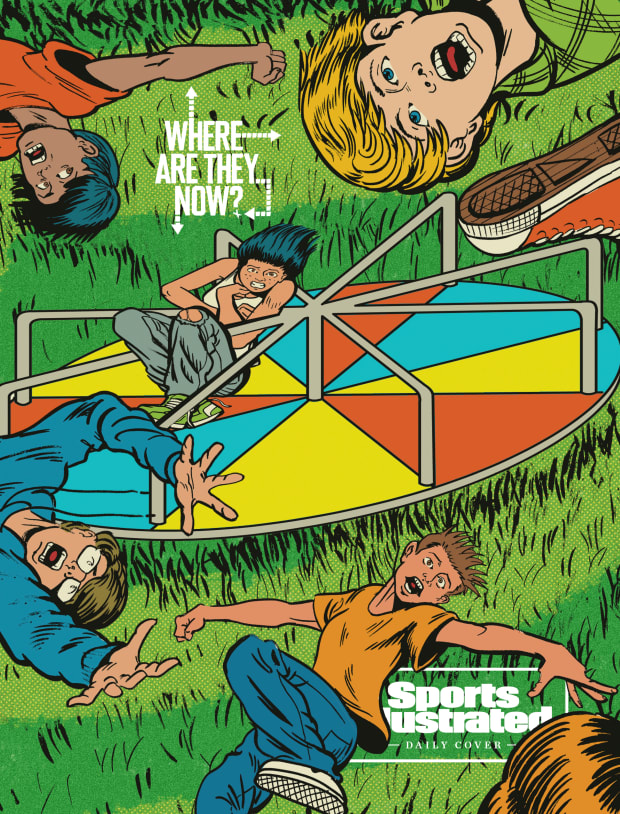

️ More from the “Where are they now?” series

If you're reading this on SI.com, you can sign up to get this free newsletter in your inbox each weekday at SI.com/newsletters.

One year of ups, downs and coaches fighting

This time last year, the world of college sports was turned on its head. On July 1, 2021, laws went into effect in 14 states allowing college athletes to profit off of their name, image and likeness. It was unknown territory, but today any sports fan knows what NIL refers to.

As we enter the second year of NIL, Richard Johnson looked back at how the laws have altered landscape of college sports, particularly football:

“NIL has further exposed just how little control the NCAA currently exerts over college sports, or at least how much it wishes to exert. Why the governing body did not put something approaching strict guidelines in place before the NIL era began boils down to the fact that the organization is being sued left and right, reportedly spending just over $300 million in outside legal expenses going back the last seven years. In many ways, the current messiness with NIL is the NCAA reaping what has been sewn over a century of inaction; more specifically, a more recent failure to be proactive about where college sports was headed. The NCAA was content to fight to preserve its definition of amateurism instead.”

The mess that Johnson refers to is a result of how rapidly the NIL industry is evolving. The state laws that allow athletes to profit off of their name, image and likeness are all different. Each school’s approach to NIL—both through the athletic department and networks of boosters—is different. In the absence of a centralized NIL playbook, chaos has reigned. Johnson points to six states that have already altered their NIL laws in the year since they were first enacted. And then there’s Alabama:

“Alabama has gone a step further, fully repealing its law in February largely because it was more restrictive than the NCAA’s scant NIL policies, which don’t actually prohibit schools from facilitating deals.”

So yeah, it’s the Wild West out there. But while schools have struggled to adjust to this new era of player empowerment, NIL has undoubtedly been a major benefit for players. It allowed Miami quarterback D’Eriq King to get paid for his football exploits even though a pro career didn’t work out. It has led people such as North Carolina basketball star Armando Bacot to delay turning pro and stay in school to reap the benefits of their college stardom. It has allowed schools formerly on the periphery of major college athletics to land big-time recruits. It has helped demonstrate the true value of women athletes, who have been among the biggest NIL earners. (The biggest benefit for fans has been entertaining drama like the Jimbo Fisher–Nick Saban feud.)

The NIL landscape will continue to change rapidly until the federal government passes legislation to control it on a national level. (Given the bigger issues before Congress right now, that’s not expected to happen soon, Johnson writes.) Until then, expect more situations like the one unfolding at Miami, where the NCAA is investigating the NIL deals struck by billionaire Hurricanes booster John Ruiz.

Between the NIL chaos and the looming new wave of conference realignment, college sports will be unrecognizable by the end of the decade.

The best of Sports Illustrated

Illustration By Felipe Flores

In today’s Daily Cover, Steve Rushin explores the history and legacy of a classic piece of playground equipment:

“Spinners were physically powered by parents and other children, but metaphorically they were powered by joy and dread. It was a ride whose only emissions were laughter, screams and airborne 8-year-olds. And vomit. So much vomit.”

For our “Where Are They Now?” package, Joseph Bien-Kahn caught up with legendary former SI writer Gary Smith, who spends his retirement teaching mindfulness to elementary school students. … Jimmy Traina reviewed ESPN’s new Derek Jeter documentary, which will debut next week. … Will Laws lists each MLB team’s biggest All-Star snub.

Around the sports world

Tiger Woods called out players who jumped ship for LIV Golf. … An autopsy found that former Cowboys running back Marion Barber III died of heat stroke. … Olympian Mo Farah revealed that he was brought to Britain as a child under a false identity. … Dodger Stadium concession workers have authorized a strike ahead of the All-Star Game. … ESPN aired a fake quote (again) attributed to Ja Morant from the joke Twitter account “Ballsack Sports.” (Ben Pickman spoke to the guy behind the account for a Daily Cover story last week.)

The top five...

… things I saw yesterday:

5. This joke about the Steelers stadium’s new name.

4. Manny Machado’s long home run at Coors Field.

3. This Chet Holmgren alley-oop.

2. Rangers rookie Josh Smith’s first MLB homer, an inside-the-parker.

1. An arena worker’s reaction to an NBA Summer League buzzer beater.

SIQ

Who came up with the idea for the White Sox’ Disco Demolition Night (held on this day in 1979)?

Yesterday’s SIQ: Which player robbed Barry Bonds of a home run in the first inning of the 2002 MLB All-Star Game?

Answer: Torii Hunter. I wish MLB had Statcast back then because I’d love to see the launch angle and hangtime on Bonds’s blast and the distance Hunter covered to snag it.

In the bottom of the first, Bonds turned on an inside pitch from AL starter Derek Lowe and gave it a ride toward deep right centerfield. Hunter and Ichiro Suzuki gave it a chase, but it was Hunter who made a perfectly timed leap at the wall to bring it back inside the field of play. Bonds and Hunter had ear-to-ear grins as they jogged off the field, and Bonds even hoisted Hunter up onto his shoulder as he went out to take his place in the outfield in a memorable display of camaraderie.

The game was supposed to be a coronation for commissioner Bud Selig, the former Brewers owner who had long fought to secure a new stadium for the team. Miller Park finally opened in 2001, more than a decade after Selig began lobbying government officials to build a new stadium.

Holding the All-Star Game at the gleaming new ballpark that Selig had finally convinced the state legislature to force taxpayers to pay for was supposed to be a celebration. Instead, it became one of the most infamous days in his tenure as commissioner.

Managers Joe Torre and Bob Brenly had been burning through their benches and bullpens, trying to get everybody in the game, which left both teams with few players available as the game went into extra innings. Vicente Padilla was on the mound for the NL in the 10th and Freddy García for the AL. They were the last pitchers available for either team. After Padilla pitched a scoreless half of the 11th, the severity of the predicament became abundantly clear. Torre, Brenly and the umpires conferenced with Selig, which produced the unforgettable image of Selig throwing his hands up in despair. They decided that, if the NL didn’t walk it off in the bottom of the 11th, the game would be declared a tie. With a runner on second, García caught Benito Santiago looking at a big curveball for the final out—and the fans went home unhappy.

From the Vault: July 12, 1993

Ronald C. Modra/Sports Illustrated

In a happy bit of coincidental synergy, today’s “Where are they now?” story about Gary Smith in retirement happens to fall on the anniversary of the publication date of an excellent story he wrote.

During spring training in Florida in 1993, Cleveland pitcher Tim Crews invited two teammates—Steve Olin and Bob Ojeda—to his home on a lake about an hour from the team’s facility. Crews was piloting a boat on the lake at night and crashed into a dock. Though the fishing boat went under the dock, Crews and Olin struck their heads. Olin was killed instantly; Crews died the next day. Ojeda suffered lacerations to his scalp that required plastic surgery to repair and said later that he believes he only survived because he was slouching in his seat.

Four months later, Smith sifted through the wreckage, detailing how Crews and Olin’s deaths impacted those around them. Smith spoke with both players’ wives, Laurie Crews and Patti Olin, as well as Cleveland manager Mike Hargrove, and their pain is palpable on the page. I was also moved by the stories of Ojeda and fellow reliever Kevin Wickander. Wickander was close friends with Olin, having come up through the Cleveland system together, and was shattered by his death. He pitched poorly and, to spare him the embarrassment of being demoted to the minors, Cleveland traded him to the Reds. Ojeda struggled emotionally after the crash and wasn’t convinced that he wanted to return to the mound. Laurie and Patti urged him to come back, though, to ensure that there was a happy ending for one of the men on the boat. Smith’s story ends on that optimistic note:

“There are black and white pipes, bundles of wires, scabbed paint and fluorescent bulbs glaring on it all in the tunnel leading to the home dugout at Cleveland Stadium. On a gray, sweltering afternoon, five hours before a night game on June 25, Bobby Ojeda walked in a Cleveland Indian uniform down the tunnel, into the dugout, out of seclusion. The cameras snapped. The microphones leaned. The tape recorders clicked on. He said it had to be done.”

Check out more of SI’s archives and historic images at vault.si.com.

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.