If there’s one thing we’ve learned over the first two games of the NBA Finals, it’s that both teams are capable of going on runs to completely bury their opponent.

Good morning, I’m Dan Gartland. I did indeed stay awake for the whole Finals game, although I’m not sure the Warriors did.

In today’s SI:AM:

☘️ A legendary fourth quarter

🥎 The College World Series are underway

An American teen goes for her first major title

If you're reading this on SI.com, you can sign up to get this free newsletter in your inbox each weekday at SI.com/newsletters.

A series of runs (so far)

If there’s one thing we’ve learned over the first two games of the NBA Finals, it’s that both teams are capable of going on runs to completely bury their opponent.

It was the Celtics who put the game out of reach with a 40–15 fourth quarter in Game 1, and last night it was the Warriors’ turn. Golden State outscored Boston 35–14 in the third quarter of Game 2 en route to a 107–88 win that evened the series at a game apiece.

Three quick buckets at the start of the fourth quarter made it a 25–2 run for the Warriors as they stretched their lead to 93–64. But the third quarter was the difference maker, as it has been for the Celtics on a few occasions during this postseason. Chris Mannix points out that Boston has now been run off the floor in the third quarter of four games over the past three playoff rounds: 34–17 in Game 3 against the Bucks, 39–17 in Game 1 against the Heat and now twice against the Warriors. In Game 1 of the Finals, Golden State outscored Boston 38–24 in the third quarter before the Celtics’ fourth-quarter outburst. Starting the second half on the right foot will be an emphasis for the Celtics in Game 3 at home, Mannix writes:

“The Celtics will have to figure out a counter when the series shifts to Boston on Wednesday. It will begin with the third quarters. ‘It’s something we have to fix,’ admitted Horford. They will need a better defense against the Warriors’ three-point shooters, including Jordan Poole (17 points) and Andrew Wiggins (11), who contributed to Golden State’s 40% shooting from beyond the arc.”

The Celtics struggled to reach the same offensive heights they reached in Game 1. Rohan Nadkarni notes that there was a huge disparity in the number of catch-and-shoot threes Boston got last night, compared to in Game 1.

For the Warriors, it was all about Stephen Curry. He had 29 points while sitting out the entire fourth quarter. Jordan Poole had 17 points off the bench (including this preposterous buzzer beater at the end of the third quarter) but the rest of the Warriors’ starters didn’t give Curry much help offensively. Andrew Wiggins scored 11 points on 4-of-12 shooting, and Draymond Green took only three shots on his way to scoring nine points. Most concerningly, though, Klay Thompson scored just 11 points on 4-of-19 shooting, including 1-of-8 from three.

“It was a winning formula for one night,” Howard Beck writes. “But it’s become increasingly clear that the Warriors’ margin for error is much slimmer now than in any of their five prior Finals—because, really, they are more reliant on Curry now than they’ve ever been.”

The good news for the Warriors is that they boast a defense capable of holding the Celtics to 88 points in a Finals game, but they’ll need to get more consistent help on the offensive end from the non-Curry members of the team if they’re going to win three more games (including at least one in Boston) to take the series. At this point, because everything runs through Steph, though, he’s more or less guaranteed his first Finals MVP if the Warriors can pull it off.

The best of Sports Illustrated

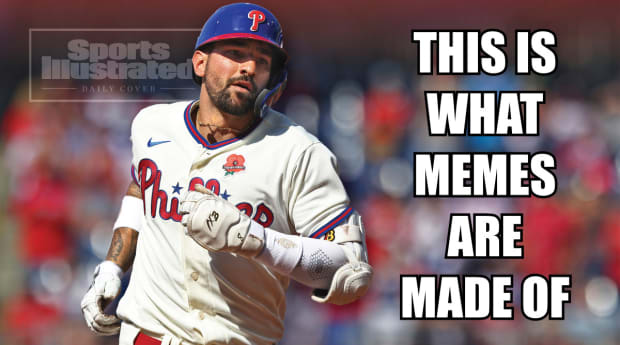

For today’s Daily Cover, Jon Wertheim consulted a sports statistician to find out just how unlikely it is that Nick Castellanos keeps interrupting solemn moments with home runs.

Avi Creditor takes a look at the USMNT’s World Cup draw, which has finally been solidified after Wales beat Ukraine in a playoff. … Pat Forde goes in depth on the recruiting battle between Kentucky and Louisville, which are both in pursuit of the nation’s top men’s hoops prospect, D.J. Wagner. … Tom Verducci argues that the Phillies had no choice but to fire Joe Girardi, who wasn’t responsible for all the team’s problems but did add to them. … Jon Wertheim has his 50 parting thoughts from the 2022 French Open. … There’s a lot of movement in Jeremy Woo’s latest NBA mock draft.

Around the sports world

Jazz coach Quin Snyder has resigned. … Here’s who could replace him in Utah. … Canada’s men’s soccer team refused to play yesterday’s scheduled game against Panama as players seek a higher percentage of World Cup revenue. … Australian Minjee Lee dominated the U.S. Women’s Open field this weekend. … At least five Rays players removed the rainbow pride logo from their uniforms on Saturday. … Evander Kane was suspended one game for his hit on Nazem Kadri that knocked Kadri out for at least the rest of the Western Conference final. … Oklahoma State and Missouri State set an NCAA baseball tournament record by scoring a combined 44 runs in a single game. … David Ortiz’s son drove in Manny Ramirez Jr. in a college wood-bat league game.

The top five...

… things I saw yesterday:

5. Defenseman Eli Gobrecht’s goal in PLL action

4. (Begrudgingly, as a Rangers fan) Ondrej Palat’s go-ahead goal for the Lightning with 41.6 seconds left in regulation

3. The unbelievable end to this Double A game: an error, a walk and four hit batsmen

2. The 2022 Jubilee Cheese Rolling Contest

1. Jordan Poole’s buzzer beater at the end of the third quarter

SIQ

On this day in 1944, the American and National leagues canceled all games in light of the allied invasion of northern France. Which two future Hall of Fame baseball players participated in the D-Day assault on Normandy? (Hint: One of them played only in the Negro Leagues.)

Friday’s SIQ: How many Power 5 schools do not have a varsity baseball program?

Answer: Four. Syracuse, Iowa State, Wisconsin and Colorado.

Syracuse finished third in the 1961 College World Series, but the program was discontinued after the ’72 season. Iowa State’s final varsity season was 2001, 30 years after its third and final NCAA tournament appearance. Wisconsin’s program was cut after the 1991 season.

Baseball was one of four sports (along with wrestling, gymnastics, and swimming and diving) cut by Colorado on June 11, 1980, when the school’s athletic department was in turmoil. A Sports Illustrated article from October of that year laid out the challenges facing the school’s “once proud athletic program.”

In honor of those departed programs, here are the best major leaguers produced by each one:

- Wisconsin: Harvey Kuenn. He played 15 seasons with the Tigers, Giants, Cubs, Phillies and Cleveland (1952 to ’66), earning eight All-Star selections and the ’53 Rookie of the Year. Kuenn played shortstop early in his career and outfield later. He finished with a career batting average of .303 and won the AL batting title in ’59 with a .353 average.

- Iowa State: Mike Myers. During his 13 years as a relief pitcher (1995 to 2007) with nine teams, he won a World Series with the Red Sox in ’04.

- Syracuse: Dave Giusti. He pitched 15 years in the majors (1962, ’64–77), first as a starter and later as a closer, primarily with the Astros and Pirates. In ’71 he won a World Series with Pittsburgh and led the NL in saves that same year with 30.

- Colorado: Jay Howell. He pitched for 15 years as a relief pitcher in the majors (1980 to ’94) with seven teams. Howell was a three-time All-Star selection and won a World Series with the Dodgers in ’88.

From the Vault: June 6, 1994

Chuck Solomon/Sports Illustrated

Two months in, the 1994 MLB season was shaping up to be a good one—perhaps even a record-breaking one. By the time Tom Verducci’s cover story was published, it looked like there was a pretty decent chance that two of baseball’s most hallowed statistical benchmarks could be equalled or surpassed: Roger Maris’s 61 home runs and the .400 batting average plateau.

Yankees outfielder Paul O’Neill started out the season on a tear. When Verducci’s article went to press, he was hitting a ridiculous .456 through 40 games (169 plate appearances).

Ken Griffey Jr. was also knocking the cover off the ball through the end of May. At press time, he had played 48 games and hit 22 home runs. If he kept up that pace for an entire 162-game season, he would have hit 74 home runs.

And there were other players poised for record-breaking seasons. The Blue Jays’ Joe Carter was racking up RBIs at a rate that would challenge Hack Wilson’s single-season record of 190. Orioles closer Lee Smith was on pace to break the record for saves. Frank Thomas had a shot to score more runs than anybody. Larry Walker was piling up doubles like nobody before. Verducci wrote:

“This season is beginning to sound like a broken record. But which one? Therein lies the beauty. With so many challenges to the game’s hallmarks, wouldn’t it be wonderful if just one of them was successful? It seems not a lot to ask. Couldn’t just one player, this one time, defy gravity?”

But Verducci also knew that the labor battle bubbling beneath the surface threatened to halt all those record chases at a moment’s notice.

“Alas, a calculator cannot account for one other element of the equation: The possibility of a players’ strike looms, as threatening to the season as a pin pressed to a balloon. ‘It’s like the alien,’ [Paul] Molitor says. ‘Just when you don't think about it, it comes back bigger than ever.’

“The players are expected to set a strike deadline at a meeting during the All-Star break in July. Eighteen months after reopening negotiations for a basic agreement, the owners still have not delivered to the players a plan to pay them under a salary-cap system. They did present other proposals last week that only discouraged the union, such as crediting players for only half of the service time for days spent on the disabled list. It seems kryptonite is not all that could stop Griffey. ‘What are we supposed to do, forgo a strike because Junior’s got 50 home runs on September 1?’ Molitor asks.”

If the season had been played in full, Griffey would have had a decent shot at 61 homers. He finished with 40 in 111 games. That’s a pace of 58 per 162 games, so he would have needed to step it up just a bit over the season’s final seven weeks to tie Maris. But Griffey slowed considerably after his hot start. He was hitting one home run per 9.4 plate appearances through May 29. From that point on, he hit one homer per 15.9 plate appearances. That’s a difference of about 30 homers over the course of a full season (73 vs. 43, based on the 691 plate appearances he made in 1993).

Though the strike did halt the season on Aug. 11, O’Neill played his way out of the race for .400 long before that. He batted .273 in the month of June (.302 overall from press time of Verducci’s article to the end of the season) and finished the year at .359, best in the American League. It was Tony Gwynn, whose average never dipped below .376 after the season’s first month, who was denied a real shot at .400. He finished at .394.

The other big losers that year were, famously, the Montreal Expos, who had the best record in baseball when the season was halted, just one of many ways in which 1994 became remembered as the year of “What if?”

Check out more of SI’s archives and historic images at vault.si.com.

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.