Though short-lived, the league provided a model—and stars—for women’s basketball as we know it today.

Before she was a three-time WNBA All-Star, Nikki McCray was a star in the American Basketball League.

In fact, she was the ABL’s MVP in its inaugural 1996–97 season.

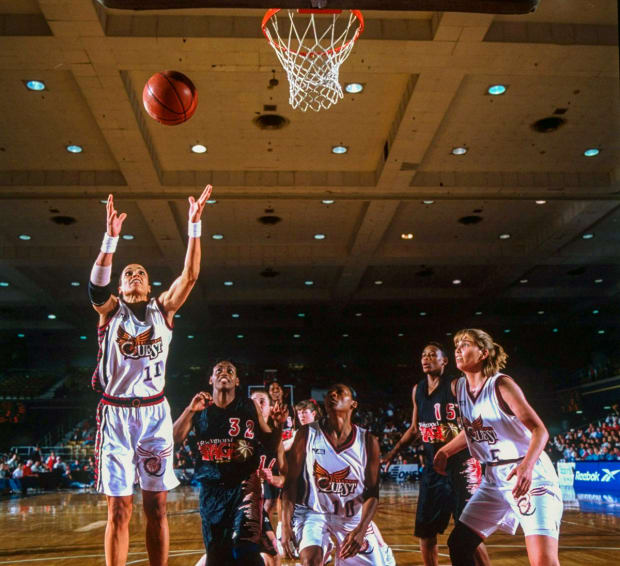

“I always say I started in the ABL. I never forget where I come from, because that league was pretty special and it will always be special,” says McCray, who played for the Columbus Quest.

The Quest was one of the league’s original eight teams. In the ABL’s brief history, the Quest was its most successful franchise, winning both championships awarded.

“That was an amazing, fun time in my life. It was kind of like being in college because it was during a normal season, so you really got the chance to get to know your teammates,” McCray says. “It was almost like a sisterhood, like you were back in college but you were really in the pros.”

As the spotlight continues to shine on women’s sports in general and the WNBA in particular—celebrating its 25th anniversary this year—it’s time to look to the past and pay homage to the ABL as a precursor to the W.

“The ABL wasn’t an afterthought. It was the forerunner to the WNBA—we were the main event,” says Valerie Still, McCray’s teammate who helped lead the Quest to back-to-back championships. She was named MVP of the championship series both times. When the ABL folded during its third season, she went on to play in the WNBA for the Mystics.

“You have to pay respect to other leagues, because part of what happens with women’s basketball is erasing our history, and if we don’t know our history, we can’t build on that,” says Still. “People think, “Only, they were only around for two, two and a half years,’ but the ABL was so far ahead of its time as far as what the players are talking about now: equal pay, health benefits, being treated with respect and more.”

Brian Agler, the Quest’s GM and head coach, who finished with a record of 82–22, agrees.

“We probably had two to three people on our team that were making more money than what the super max is in the WNBA, so that’s why I say we were ahead of our time,” he says.

The longevity of the WNBA can also be attributed to this fact, Agler says. “That is why the WNBA has played the long game and started off slower, created the game in the summertime so players could go to Europe and play and make more money. That ended up working for the long term.”

In 1996, women’s basketball was growing in popularity thanks to the U.S. national team, undefeated gold-medal winners at the Summer Olympics. It was these same medalists, McCray, Dawn Staley and others, who made up the majority of the players signed to the new league.

The ABL was the first independent professional basketball league for women in the United States. It formed simultaneously with the NBA’s creation of the WNBA. The ABL began league competition in the fall of 1996, while the WNBA launched its first game in June 1997.

The two leagues did not directly compete—the ABL played during the winter while the WNBA played during the summer—and both showcased the talents of woman athletes.

“I have to give props to where props are due,” says McCray. “I thought the ABL really stepped up with getting that league off the ground full steam ahead. It was very competitive. We had a lot of the top players from colleges playing, the Olympic team—it was just loaded with talent. Everywhere we went we had really good fan support. People fell in love with our teams. It was truly unbelievable. It was at the time what we needed.”

The Quest team in particular was the darling of the league.

“Brian did a great job of putting together a great group of individuals that made us a great team,” McCray says. “We had a clear understanding of what winning looked like. Our team was just stacked in terms of character and winning. It just allowed us to dominate.”

Shannon “Pee Wee” Johnson was the point guard and the glue that helped keep the Quest together during their two-year championship reign.

“All of us were just willing to sacrifice. We all did what it took to become champions. Brian was our leader and Coach [Kelly] Kramer was right there with us,” she says. “Players put their egos in check. We played as a unit. That’s how we were successful.”

Adds Still: “Everything just clicked. We loved playing. Brian Agler had this system that was so brilliant, you couldn’t scout it. You had young players and vets who came in. We had everything going for us.”

But it wasn’t enough. The WNBA’s backing and marketing from the NBA prevailed, and after two full seasons the ABL declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy and suspended operations midway through its third season, with many of its players moving over to the W.

“It was hard,” McCray says. “When you have the NBA behind the WNBA, you know, can two leagues be sustained? I think that became a big question, and obviously the NBA is a powerhouse. And now, 25 years later, who knew? The WNBA is still rocking the boat.”

The ABL’s folding and being absorbed into the WNBA was “the most transformative moment for the WNBA,” says Kramer, the assistant coach on the Quest team. “We had a high quality of players, that’s the way it was, and when our players were absorbed into that league, that completely changed the WNBA for the better.”

Still was out with a knee injury when the news came that the league was folding.

“We were a family, especially the Quest. We just trusted and loved each other,” she says. “When I found it, it was just devastating. I think it was just the shock, but things happen for a reason. It was like a death in the family.”

Even more distressing was the fact that once the ABL was done, there were no pensions or money for the players to fall back on. Some talked about filing for unemployment, but they didn’t know much about it, Still says.

“We were professional athletes,” she says. “That’s ridiculous that pro athletes would find themselves in that situation, but as women, that’s what happened to us. We were just out of jobs.”

Johnson, who had just brought her family up to Columbus for Christmas, said the memories of what they had shared is what got them through the folding of the league.

“When it happened it was kind of devastating, but we were also thankful and blessed for the opportunity. And that’s what I look at my experience in the ABL as: an opportunity to kind of put myself on the map,” says Johnson, who played for several teams in the W, including the Orlando Miracle, Houston Comets and Seattle Storm.

The short-lived success of the ABL and the current 25th anniversary of the WNBA shows that there is indeed an audience for women’s basketball and that women’s sports leagues in general can be effectively marketed and supported worldwide, McCray says.

Doing so includes looking back at what was and the role it played on what is.

“We have to remember our history,” Still says. “Reckoning and giving honor to those women who were really taking the hit because it wasn’t cool to play sports and they were doing it anyway.

“I was fortunate to play in the ABL and the WNBA, and I will alway recognize those women that came before me.”

• How One Hoodie Became the WNBA’s Defining Symbol

• The 25 Greatest Moments in WNBA History

• Cynthia Cooper Is the WNBA’s Unsung Star

• How No. 1 Picks Realized a Career in the WNBA Was Possible