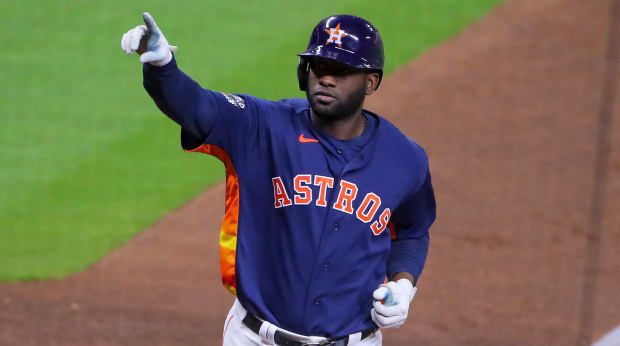

Houston’s attention to the smallest of details paid off big time on Yordan Alvarez’s go-ahead home run in Saturday’s title-clinching Game 6.

HOUSTON — An hour and a half before Game 6 of the World Series, the Astros won the title. Hitting coach Alex Cintrón knew it. Utilityman Aledmys Díaz knew it. Most importantly, even before he hit the 450-foot, game-changing bomb he called the best moment of his career, left fielder Yordan Alvarez knew it.

They still had to play the game. Lefty Framber Valdez had to baffle the Phillies’ dangerous lineup for six one-run innings, just as he had in Game 2. The defense had to turn the few balls Philadelphia put in play into groundouts. The hitters had to grind through 20 plate appearances against Phillies ace Zack Wheeler, who reared back for 98 mph and found it. They had to wait until Nick Castellanos’s loopy fly ball nestled into right fielder Kyle Tucker’s glove, just shy of the wall down the line, to seal the 4–1 victory.

(It’s a good thing the Astros won the World Series in Game 6, because they would have been very hobbled if the series had made it to Game 7. Third baseman Alex Bregman told Sports Illustrated early Sunday morning that he believed he had broken his right index finger sliding into second base in the eighth inning, and that second baseman Jose Altuve had strained a hamstring going first to third in the sixth.)

This title caps a span of four World Series appearances in six years and six straight trips to the American League Championship Series. If you were not already using the word dynasty, it’s time to start. This team could have been destroyed by the revelation after the 2019 season that its players participated in an illegal sign-stealing scheme en route to the ’17 championship; instead it has merely played in two more World Series in the three years since then. But the Astros are not inevitable, as they sometimes seem as they streak through October after October. Sustained success such as this requires excellence in many areas: scouting, player development, clubhouse culture. And attention to detail.

Troy Taormina/USA TODAY Sports

These all converged in the bottom of the sixth inning, with Philadelphia up 1–0, after Wheeler hit Martín Maldonado with a pitch to lead off the frame. Altuve barely beat out a double-play ball, and shortstop Jeremy Peña singled him to third. Phillies manager Rob Thomson summoned lefty José Alvarado, as he had all series, to face the Astros’ most lethal hitter, Alvarez.

For the most part, that had gone pretty well. Alvarez, whom the Astros had swiped from the Dodgers in 2016 for reliever Josh Fields, showed up as a skinny 20-year-old with one career home run in two seasons in the Cuban National Series. The Astros stressed to him in the minor leagues, as they do with most prospects, that he should try to pull the ball for power, and he finished third in the AL this season with 37 homers. But since he almost singlehandedly swept the Mariners in the ALDS and stopped seeing pitches in the strike zone, he had been hitting .119 with two-extra base hits, both doubles. He’d had two hits in the World Series. In his three meetings with Alvarado to that point, he had popped out twice and been hit by a pitch.

But what Thomson did not know is Alvarez was not the same hitter he had been over the past three weeks. He was not even the same hitter he’d been four hours earlier. Before Game 4 of the World Series, the Astros’ other hitting coach, Troy Snitker, had noticed that Alvarez was shifting all his weight onto his front leg. Cintrón worked with Alvarez in the cage to keep him more balanced. They saw improvements—a single to center, a lineout to left, a flyout to center—but Cintrón still felt there was work to do. We need to get Yordan going, he thought.

Early on Saturday, before Game 6, Cintrón scoured video from June, when Álvarez hit .418 with a 1.346 OPS, and he realized that the player’s hands had dropped, making it harder for him to get to the fastball. He called in Díaz, whose eye he trusts on such things and who sometimes helps him communicate with other players.

“You know what?” Díaz said. “You’re right.”

Cintrón texted Alvarez: I found something. Come to the cage.

Initially, Alvarez was unsure. He believed the problem still resided in his lower half.

“Yordan, do you trust me?” Cintrón asked.

“Yes,” Alvarez said.

“Then give me five swings in the cage and see how you feel. If you don’t like it, then you change it.”

It didn’t take five swings. Alvarez felt the change immediately. Díaz and Cintrón saw it. They all knew what it meant: “Game over,” said Cintrón later, dripping with an unholy brew of Bud Heavy, Michelob Ultra and Korbel. “I was so pumped,” he said. “I told the front-office guys, the player of the game is going to be Yordan Alvarez.”

Erik Williams/USA TODAY Sports

So when Alvarez strode to the plate in the sixth, he was not the man who had a few days earlier slammed his batting helmet in frustration. He was the man ready to slam something else.

He fouled a sinker down the first base line. He took a cutter outside and a sinker up. Alvarado threw him another sinker, 99 mph, on the outside part of the plate. This time, Alvarez got to the fastball.

The center field wall in Houston stands 409 feet from home plate. The batter’s eye rises 40 feet. The Astros joke during batting practice that only Álvarez, who had the second-hardest average exit velocity in the game this year, after the Yankees’ Aaron Judge, has a chance of putting a ball there.

“I try to hit the warning track in center field [during BP],” said Bregman. “He tries to hit it over the batter’s eye.”

Even Alvarez had never made it up there before. But as he watched the ball rocket out there, he pounded his chest, because he knew exactly what he had done. The Astros spilled out of the dugout. Initially Bregman was not among them. “He hit it to dead center!” he said. “I was like, Does he think he got this?” He added, “Nobody hits the ball up there. Nobody hits the ball up there.”

“There are some places where only Yordan can go,” Snitker said.

“He’s a strong boy,” said Peña.

GM James Click, watching in his suite, unleashed a string of expletives. “I’ve heard a lot about lefty sinkers being the way to get Yordan out, and I think somebody needs to write a new scouting report,” he said.

Afterward, first base coach Omar López joked with Alvarez that if they had been in Venezuela, he would have had Alvarez’s bat checked for cork. (“In winter ball, a lot of crazy stuff happens,” López explained, laughing. “That was a bomb.”)

As he circled the bases, Alvarez said, he wondered whether Minute Maid Park would cave in from the roar. “I felt like the ground was shaking,” he said through interpreter Jenloy Herrera.

Alvarez beamed as he circled the bases. He felt joy, excitement, relief. But he did not feel surprise.

More MLB Coverage:

• The Astros Are World Series Champions—No Asterisk Needed

• Destiny Denied: Phillies’ Cinderella Run Falls Short of the Finish Line

• Astros Win World Series to Secure Place as Premier MLB Team

• Verlander Completes Epic Comeback Year With First World Series Win

• Cristian Javier Rides His ‘Invisi-Ball’ to a Storybook World Series Win