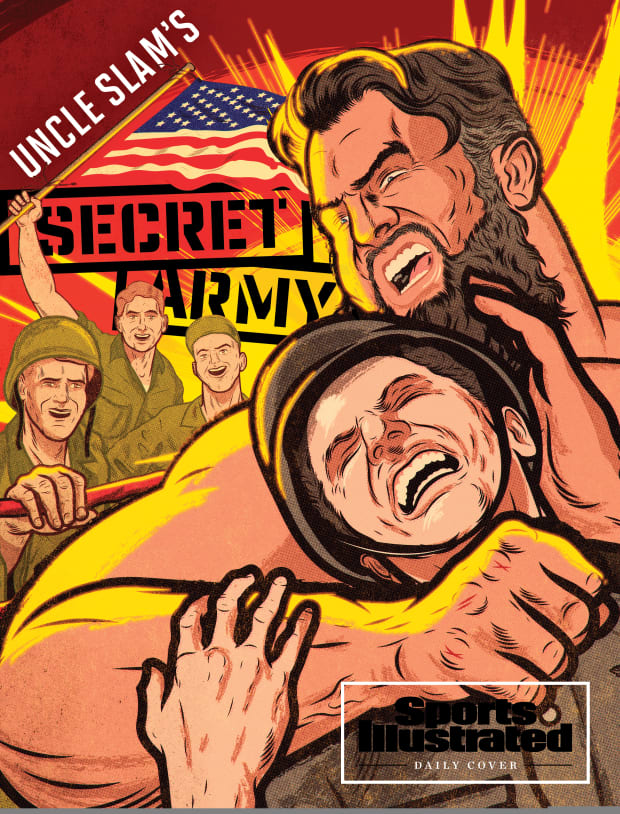

He was Hulk Hogan before Hulk Hogan. He leapt to the big screen before it was the sporting standard. And for his final act? He worked in the shadows to topple Hitler.

For a few days in 1943, the rumor rocketed around the Camp Ritchie military training center in the Maryland hinterlands. The scuttlebutt went something like this: A famous and cartoonishly muscled professional wrestler, who lately had been moonlighting as a movie star, would be giving the new soldiers a crash course in hand-to-hand combat before their dispatch to the Western Front.

It was, of course, preposterous on its face—the World War II equivalent of, say, The Rock suddenly showing up at basic training as an instructor. Then again, the entire tableau was already a study in surrealism, a straight-out-of-Hollywood conceit. Camp Ritchie had been a vacation resort, framed by the Blue Ridge Mountains, just under the Pennsylvania state line. After the war broke out, though, it was quickly morphed into a military intelligence training center. The U.S. Army recognized the need for translators and interrogators who spoke fluent German and understood the culture of the enemy. What better location to train than this, nestled unassumingly in the countryside but easily accessible to D.C.’s decision makers?

Camp Ritchie’s soldiers, such as they were, did not exactly cut the figure of G.I. Joe. Many of the recruits were not only new to the United States military, they were also new to the United States. And a large subset were German immigrants who now were preparing to fight in and against their country of origin.

Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

The Ritchie Boys, as these outsiders were quickly shorthanded, were mostly intellectuals, more likely to have reported for duty equipped with musical instruments and books than with guns and knives. And now they were going to be trained by a pro wrestler?

That rumor crossed the DMZ into truth one afternoon when a few cadets walked by the camp’s phone booth. There they saw a man, shorn of his famous beard, per Army rules, but instantly recognizable for his sheer girth. He was roughly the size of one of the bluffs that sprung up behind the camp, and here he was, on the exterior of the glass cube, extending one arm inside, yanking out the receiver. Unable to squeeze in his 320-pound frame, this was the only way that Frank Simmons Leavitt—Man Mountain Dean, as he was widely known outside of Camp Ritchie—could place a call.

As the name implied, Man Mountain was a considerable physical specimen. He doubled many of the other soldiers in weight. Though he stood a modest six feet tall, he still had eight inches on the median Ritchie Boy. And while Leavitt’s precise age remains a source of debate, he likely arrived at Camp Ritchie in his early 50s, making him a full three decades older than many of his trainees.

When World War II broke out, Man Mountain had been coming off the height of his popularity. Not much earlier, he was pinballing around the country—and then the world—as a bearded babyface, theatrically tossing opponents out of the ring, flattening them on the canvas. For this he could command upward of $1,500 a night, which was more than the annual per capita income in the U.S. at the time. And when Leavitt wasn’t inside the squared circle, he was on the silver screen, starring in movies and working as a stuntman.

For all of these surface differences, though, Leavitt was, by all accounts, beloved by the Ritchie Boys. He had charisma to burn, and the kind that rarely intimidated. Soldiers listened raptly to his stories about wrestling romps through venues familiar to them across Europe. They gawked as he put on heroic eating displays. Here was an American celebrity dispensing Americanized nicknames—every Gustav became a Gus—and teaching them slang.

Man Mountain, though, wasn’t just the equivalent of the cool camp counselor. He was also a brutally effective teacher. According to K. Lang-Slattery, who wrote about the Ritchie Boys in her book Immigrant Soldier, Leavitt’s charges “soon got over their awe of the huge and famous instructor. From him, they learned how to fight the enemy, individual against individual.”

As U.S. military documents have been gradually declassified in recent years, the full effectiveness of the Ritchie Boys has come into sharp relief. This extraordinary unit was responsible for more than half of all combat intelligence gathered on the Western Front, their work pivotal to the Allies’ victory. They were fanned out into other military units abroad and proved the most improbable of war heroes. And the identity of their comically oversized mentor and instructor—well, that, too, was wildly unlikely.

Frank Leavitt was born in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan, a few blocks from the theater where his father was a stage manager for Broadway impresario George M. Cohan. Even as a young boy, Frank was monstrously large; in his early teens, he was assumed to be a full-grown adult.

He wasn’t, but that didn’t curb—and may have intensified—his desire to enlist well before World War I broke out. After allegedly paying a down-and-out stranger on the Bowery to impersonate his father and sign in person the necessary papers, Leavitt was accepted into the Army. (This contributed to the mystery around his birthdate, which is generally recorded as June 30, 1891.) He ended up doing five terms of service, across nearly two decades, under General John J. Pershing, including a stint on the Texas side of the Mexican border. He was then sent to France, where he saw action.

Leavitt would later say that his education ended in the fifth grade, which is effectively true, even if he was recruited after the Great War to play college football. “I attended five colleges,” he claimed, “but never went to class.” In 1921 he played for the New York Brickley Giants in what would become the National Football League, and he was said to have faced Jim Thorpe.

Leavitt, though, was truly seduced by a different sport that was piercing the American consciousness—one that was, potentially, far more lucrative. Given Leavitt’s theater upbringing, he found great appeal in pro wrestling’s combination of athleticism and dramatic flair. And he enjoyed interacting with the crowd in a way he never could as a football player.

He started out as Soldier Leavitt, a nod to his time in the military. And in the early days, as fans grappled with whether his new sport was real or staged, the principals performed at an astonishing clip. At one event in 1919, Leavitt reportedly beat 19 men to win the King’s Wrestling Tournament in London. “Lots of times,” he later told The Atlanta Constitution, “I fought 14 bums in one day.”

Alton H. Blackington Collection, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries

The Hell’s Kitchen kid who snuck into the Army, became a pro wrestler and then played against Jim Thorpe—it’s tempting to deem Leavitt a figure worthy of Damon Runyon. Except that, in this case, it was literally true. Runyon, the old newspaperman, was a close friend, and he conferred on Leavitt one early in-ring nickname, Hell’s Kitchen Hillbilly, thinking his pal needed something more exotic than a military reference. Leavitt committed to the redneck motif, growing a comprehensive beard—“a facial hedge; a thick, dusky shrubbery,” one newspaper reporter called it—and then hit the road.

When it became clear that Hell’s Kitchen Hillbilly was an oxymoron that confused fans, Leavitt pivoted to Stone Mountain, a nod to the precipice outside Atlanta. However, when Leavitt toured Germany in the 1920s, promoters complained that Stone Mountain was meaningless. Which is how Leavitt landed on Man Mountain.

By the end of that decade, though, the sport was wearing the Mountain down. A series of injuries sidelined Leavitt from wrestling, and he headed to Miami, where he took a job as a policeman. Surely Florida’s largest traffic cop, Leavitt was stationed one day on the corner of Flagler Street and Second Avenue when he bumped into a young out-of-state visitor, Dorris Dean. Or she bumped into him. According to newspaper accounts, Dean almost clipped Leavitt with her car while he was directing traffic. He forgave her, and they began dating. “I gave her hell,” he once said, “and then I married her.”

In 1930, barely a year after their nuptials, Leavitt was fired from the force on account of his close friendship with Al Capone. One account, in the Miami Herald, noted that Leavitt was summarily dismissed for “conduct unbecoming an officer” after he admitted to making several trips to the crime boss’s home in Palm Island. Leavitt tried to draw a line, telling the Tallahassee Democrat: “We were friends, all right . . . but they said I was a Capone gangster.”

Suddenly unemployed, Leavitt retreated to Norcross, Ga., home of Dean’s family estate, and then to the wrestling ring, where he embraced the sport’s theatricality more lustily than ever. The Atlanta Constitution described his signature move, the “blimp fall,” thusly: “After he had airplane-spun and bodyslammed his adversaries to the floor, instead of applying the ensuing body block conventionally with arms and legs, he leaped high into the ozone, distended his limbs and plopped the south end of his massive carcass kerplunk on the victim’s tummy.”

Dean, meanwhile, convinced her new husband to take on her maiden name, as it sounded more Anglo-Saxon than Leavitt. She was especially concerned that if he wrestled in Nazi-led Germany, authorities might erroneously think he was Jewish. She also took over the role of managing him. And while her primary duties were scheduling bookings and overseeing finances, she didn’t always stay on the sidelines. Per the Tallahassee Democrat: “When opponents get too rough, she goes into the ring herself with [a] chair, or water bucket, or whatever impromptu weapon comes [in] handy.”

Anthony Camerano/AP

Under promoter Jack Pfefer—a colorful character in his own right who came to the U.S. in the 1920s as a musician in a visiting Russian opera troupe—the newly christened Man Mountain Dean traded on a military background, a biblical beard and a beguiling combination of New York bona fides and Southern charm. Sometimes he was the face, other times the heel. (He was once suspended from wrestling in California for “being such a mean cuss.”) And it all rendered him a main-event-caliber star, who reportedly wrestled in 6,783 matches by the end.

Among them: Man Mountain Dean claimed to be the first wrestler to lose a match without laying a hand on his opponent. In Madison Square Garden, in the 1930s, he was supposed to wrestle 6' 7" Roland Kirchmeyer, but as Man Mountain made his way up the aisle he was confronted by Joe Savoldi, a wrestler from the previous bout (and a former football player himself, under Knute Rockne at Notre Dame and George Halas with the Bears). “Go on up there and take yer beating, ya fat slob,” Savoldi barked. Man Mountain stopped, in his words, “So I could reach out and sock him into press row. A typewriter slits his eyebrow open. And before I can get into the ring to fight Kirchmeyer, I’m disqualified.”

Other times, by the script, he got as bad as he gave. In the late 1930s, in San Francisco, Man Mountain took on “Wild Bill” Longson, the wrestler credited with inventing the piledriver. Leavitt outweighed his opponent by nearly 100 pounds, and at one point—either by stomping on him or throwing him out of the ring—he “broke” Longson’s back. Longson, the plotline went, returned home to Salt Lake City, recuperated and donned a plum-colored mask to resume his career under the name The Purple Shadow. He requested a match against Man Mountain Dean and—revenge!—broke choreography, contorting Man Mountain and snapping his left leg. Then he removed his mask.

It was around this time that wrestling’s popularity in the U.S. hit a snag. Historians pinpoint the precise moment: On March 2, 1936, Danno O’Mahony fought Dick Shikat for the World Championship at MSG. Shikat, a heel who was assigned to lose, departed from the script and applied a hammerlock to O’Mahony. And O’Mahony, his lack of true skill exposed, was forced to submit. The famed “double cross” eroded fan confidence and undermined “the trust”—akin to “the commission” of the underworld—leading to the creation of various vague organizations.

Back in Georgia, “rehabbing” his leg, and with his sport suddenly on the wane, Leavitt pivoted to acting. Having grown up a neighbor of George Raft—who went on to become one of the great Hollywood stars of the time—Leavitt had always been seduced by the film industry, and now he was able to use his imposing physique and his flair for the dramatic to break into the business, starting with a 1933 job in the U.K. as Charles Laughton’s stunt double in The Private Life of Henry VIII.

Over the next two decades, Leavitt appeared in dozens of films, the most notable of which had him portraying himself alongside the popular comedian Joe E. Brown. In that 1938 movie version of The Gladiator, based on the book that inspired the Superman comics, Brown played a college student who takes an experimental drug that promises superhuman strength. In the end, he challenges Leavitt to a wrestling match . . . just as the drug wears off.

Santa Monica History Museum/Bill Beebe Collection

By the time Leavitt reached his 40s, though, that film-friendly body was beginning to betray him. Already wealthy, he dialed back the wrestling. Off the road, he returned to Norcross—coincidentally, not far from Stone Mountain—and became a sort of gentleman farmer, working a 20-acre plot of land alongside the Buford Highway.

He enjoyed the role of small-town celebrity, glad-handing and promoting local theater. One longtime Norcross resident would later recall that, as a boy, he encountered Leavitt at the town hardware store. There a group of men expressed doubt that Leavitt was as strong as he purported to be on the big screen and in the wrestling ring, and a wager followed. The men bet $10 that Leavitt couldn’t straighten a horseshoe, whereupon one was retrieved from the town blacksmith. The horseshoe was promptly straightened, and $10 was handed over.

In 1938, Leavitt ran for a seat in the Georgia state legislature, representing Gwinnett County; then he withdrew. Ironic for a man who’d spent decades play-acting the heel, he had no taste for the battle of politics, and he resented his opponent’s verbal attacks. Leavitt would eventually study journalism at the Atlanta branch of the University of Georgia. He refereed local wrestling matches. After a quarter century of wrestling—and all that travel—Leavitt took to life in repose.

Then, in December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

At the beginning of World War II, the U.S. military considered so-called “enemy aliens” to be a security risk. Immigrants from Germany, Japan and Italy were ineligible to enlist. But after a few months of fighting, tactics changed. Recognizing that anyone who knew the enemy’s language and culture could be a useful asset, the Army established a new secret military intelligence installation in bucolic Camp Ritchie, Md., where the largest subset of its 11,000 thick-accented recruits were German-born Jews who’d fled to the U.S. to escape Hitler.

Says David Frey, a history professor at West Point and the director of that campus’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies: “The most important part of the [Ritchie Boys’] training was that they learned to do interrogation of civilians and prisoners of war. But they also did terrain analysis . . . photo analysis and aerial reconnaissance analysis. They did translation. They did night operations. They did counterintelligence.”

In anticipation of their seeing action, particularly on the Western Front, these unlikely new soldiers first had to be trained. And for that they had an instructor who was, at once, born for the job and almost comically unlikely.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Frank Leavitt told a friend, “I know what I have to do.” Though already in his early 50s, he reenlisted. He was too old for active duty, but one officer had an idea: At Camp Ritchie, Leavitt could bring to bear his experience, his accumulated wisdom and his outsized personality.

At the secret camp, where he arrived ranked master sergeant, Leavitt was immediately an object of curiosity. The Ritchie Boys included the likes of J.D. Salinger, David Rockefeller, John Kluge and Eugene Fodor, and they would go on to esteemed careers in literature, banking, media and travel writing, respectively—but at the time they were new Americans and sons of immigrants, as young as 19, and they were awed by the resident celebrity. As one Ritchie Boy, Burton Hastings, would later put it: “[Leavitt] was the hero of our era. We all knew about him.”

As part of his work, Leavitt taught these admirers, among other things, hand-to-hand combat. Lang-Slattery quotes one Ritchie Boy, Gerd Grombacher, recalling that Man Mountain taught him how to kill an enemy with a stiletto knife—“and how to make it so clean that it wouldn’t even hurt.”

Leavitt also put his acting chops to good use. As part of the training, Camp Ritchie featured an ersatz German village, replete with enemy tanks made out of cardboard. And, according to military historian Beverley Eddy, one of Leavitt’s jobs was to play the role of Hermann Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe, in mock “Hitler rallies” that were meant to introduce enlistees “to the fanaticism of the Nazi party.”

Not everything was so dark. Lang-Slattery recounts an exchange between two Ritchie Boys at the PX, or post exchange. At one point Leavitt sauntered by the on-base retail store, and one G.I. dared another to challenge Man Mountain to a fight. Leavitt didn’t even need to stand up. From a sitting position he lifted the brave soldier up by the collar and threw him to the ground. The man was so humiliated and angry about the dare—and so clearly unable to retaliate—that he slugged his friend instead.

Dan Peterson, a longtime BYU professor whose father passed through Camp Ritchie, recalls another tale that his dad used to tell of soldiers sleeping in the barracks, awoken to high-decibel snoring. As the story goes: One of those soldiers demanded to know who was breathing “like a damned freight train.” And a booming voice responded, “That was me.” Says Peterson: “[Leavitt’s] answer fully satisfied the curiosity of the angry complainer, and Father recalled with amusement that nobody else in the barracks ever complained thereafter.”

In 1944, most of the Ritchie Boys headed off to Normandy, where one of Leavitt’s charges, now 98-year-old Victor Brombert, a retired professor and dean at Yale and Princeton, remembers the terror of being strafed at night: “I never calculated that there is such a thing as terror, fear,” he says. “So I experienced, viscerally, fear.” The Ritchie Boys would go on to help liberate France, fight in the Battle of the Bulge and then help liberate the concentration camps. Overall, they were responsible for an unquantifiable trove of valuable battlefield intelligence, critical to the Allies’ victory.

After the war, many stayed in Europe to help denazify Germany and work as translators at the Nuremberg trials. Many, too, used their Camp Ritchie training and went on to become spies and CIA agents.

“We look at this group and we see true heroes. We see the greatest of the Greatest Generation,” says Frey, the West Point professor. “These are people who made massive contributions, who helped shape—who stretched—the idea of what it meant to be American. We should recognize the great diversity of those who played a role in the American army, and continue to do so.”

U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence Command History Office, Fort Huachuca, Arizona

After the war, Frank Leavitt returned to his estate outside of Atlanta. On May 29, 1953, when he was 62, he finished up some yard work outside his home. He sat on the couch to listen to a baseball game on the radio. And then he complained that his chest hurt. Within minutes he had suffered a fatal heart attack.

Edwin Pope, then a cub reporter at the Constitution—and later a towering figure in U.S. sports journalism—was assigned to write the obituary. He called Leavitt “the most fabulous wrestler of his time.” Few, though, would know the whole of it.

Leavitt did not, by all accounts, speak much about his time at Camp Ritchie. That intelligence was classified. Long after his death, even family members had no idea that the contributions Uncle Frank made to the national fabric were, well, truly mountainous.

So, of course, was the irony of it all. An American archetype spends decades following the crafted choreography of early professional wrestling and the scripts of early Hollywood. Meanwhile the unscripted version of the life story he authored himself was richer and more meaningful.

Jon Wertheim was part of a team at 60 Minutes that produced a three-part segment last year on the Ritchie Boys.

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories:

• A Physical Therapist to the Stars, Esther Lee Is Now Facing Down Death

• Does the NBA Have a $@&!*% Problem?

• The Fight For the Soul (and the Dollars) of the Fastest-Growing Sport in America