An excerpt from the book Five Laterals and a Trombone looks back at the days following one of college football’s most famous games.

This excerpt from Five Laterals and a Trombone by Tyler Bridges is reprinted with the permission of Triumph Books. For more information and to order a copy, please visit TriumphBooks.com/FiveLaterals.

On the day after the game, Joe Kapp’s home phone wouldn’t stop ringing. Word of Cal’s improbable last-second triumph had spread throughout the country the old-fashioned way—through newspaper articles, phone calls, radio news and some TV broadcasts. Brent Musburger introduced the play to his national audience by showing it twice that Sunday on CBS’s top-rated pregame show, The NFL Today, which he hosted. Sportswriters, TV producers, radio announcers, former teammates, longtime friends—all called Kapp wanting to hear how Cal had pulled it off. Kapp spoke into one of the bulky, cordless phones from the era that allowed him to roam around the house as long as he didn’t stray too far from the phone’s base. Because of the calls, he didn’t get to bed until late that night.

On Monday morning, two days after the game, a houseguest named Ned Averbuck offered to drive Kapp to the Berkeley campus. Averbuck and Kapp had played basketball together at Cal in the late 1950s and remained close. On the drive over, they talked about the game and the immediate aftermath. “Did you see [John] Elway’s comments after the game?” Averbuck asked his friend. “He said that the officials ‘ruined’ his last college game! What sour grapes!”

Courtesy of Triumph Books

Kapp was silent for a few seconds. “Did I say anything to you about the Stanford drive before The Play?” Kapp finally asked.

“No,” Averbuck replied.

“I’ve been telling every journalist to look at that final drive,” Kapp said. When they arrived at Cal, Kapp insisted that Averbuck accompany him inside to watch the fourth-and-17 pass completion. An equipment manager wheeled in a little portable TV and cued up the video.

“Watch this,” Kapp told Averbuck. He held a remote control in his hand, replaying the video twice. “Watch this pass!” Kapp said. “Watch his feet! Look at the release of the ball! He put the ball where the receiver couldn’t drop it!”

Kapp paused as they turned off the TV. “Did you just see that? That is the greatest quarterback of a college football team I have ever seen!” He paused again and added, “They made only one mistake. They celebrated too early. They went against everything we’ve been taught. I understand the young man’s disappointment. I really do. Because what he did was magnificent. I can’t take that away from him.”

Averbuck asked Kapp whether he voted for Georgia running back Herschel Walker for the Heisman Trophy. “I proudly voted for John Elway,” Kapp said.

“You mean you didn’t vote for Herschel Walker?” Averbuck asked.

“Ned,” Kapp replied, “take Herschel Walker off Georgia, and they’re still pretty damn good. You take John Elway off Stanford? We would have beaten them by a lot.”

A little later that day, the Axe reappeared in public during a noon rally at Sproul Plaza in the middle of the Berkeley campus. Naturally, Cal students remained ecstatic after Saturday’s victory, and members of the Rally Committee’s Axe Guard were more than happy to supercharge the celebration by bringing the trophy out of its hiding place. The Cal Straw Hat Band played spirit songs, and everyone reveled in the Big Game triumph. Afterward, the Axe Guard and the band paraded around campus, bursting into lecture halls to display the return of their prize. Students loved it. Even serious professors didn’t mind the interruption.

Controversy over whether Cal had scored a legitimate touchdown continued to cast a cloud over the Bears’ victory, at least in the eyes of some. John Crumpacker gave credence to Stanford’s argument in a story published in the San Francisco Examiner on Monday. “Careful inspection of the kickoff on video tape in ultra-slow motion shows that [Dwight] Garner’s progress was definitely halted by four Stanford tacklers, and his knee appeared to hit the AstroTurf a fraction of a second before he lateraled back to [Richard] Rodgers at the Cal 48,” reported Crumpacker, who, as a Cal graduate, was no Stanford partisan. “At best, Garner’s lateral was simultaneous to his knee hitting the ground. Regardless, the play was not whistled dead.”

Crumpacker quoted Paul Wiggin, still angry but calmer than on Saturday. “He was stopped, held, turned back and down on his knees and then lateraled,” Wiggin said. “It’s too bad the game had to be determined by the officials. I know of no appeal. Andy [Geiger] knows of no appeal, but the damage is done. The bowl game is out, a winning season is out and probably some honors for John Elway are out. It was a very costly play for Stanford’s football program.”

On Sunday, Geiger appealed the call to the Pac-10. He knew his chances of overturning the result were slim to none, but he still had to try. A retired referee working for the Pac-10 had already backed up the officials in his postgame report. “A very well worked ball game,” wrote Chad Reade. The form included a box to indicate the type of game it had been. Reade checked the “routine” box and added in an enormous understatement, “except for last four seconds.” Reade wrote that the six officials believed that Garner “was still squirming with the possibility of still going” when he lateraled the ball. Reade did not address whether Mariet Ford’s final lateral had been forward.

On Monday, Wiles Hallock, the Pac-10’s executive director, did not even address those two issues. His one-page statement only acknowledged that Cal had four players—not the required five—within five yards of the restraining area for the final kickoff. But, Hallock added, the official was supposed to tell Cal to move up a player to get to five. It was not something that would draw a flag and force a re-kick. “The official,” who was Jack Langley, “was subject only to human imperfection, imperfection under circumstances even the least charitable might be expected to understand. All officials and those responsible for officiating feel as deeply as the participants affected the impact of their human frailty on the outcome of games.”

Hallock added a last word. “This incredible final play of the 1982 Big Game and the scrutiny it has received apart from its uniqueness provide proof … that officiating is an element not to be set apart from but always considered as part of the game,” he wrote. “That’s one of the reasons why the Pac-10 Conference permits no protests in the sports of football and basketball.”

For almost 20 years, the Stanford band had enjoyed a charmed existence after going on strike in 1963 and becoming a scatter band that played rock ’n’ roll. Sure, conservative alums and university officials regularly pined for a traditional outfit, but students and the outside world mostly loved their act. National publications typically wrote reverential reviews of the band. But now they were about to become a punching bag.

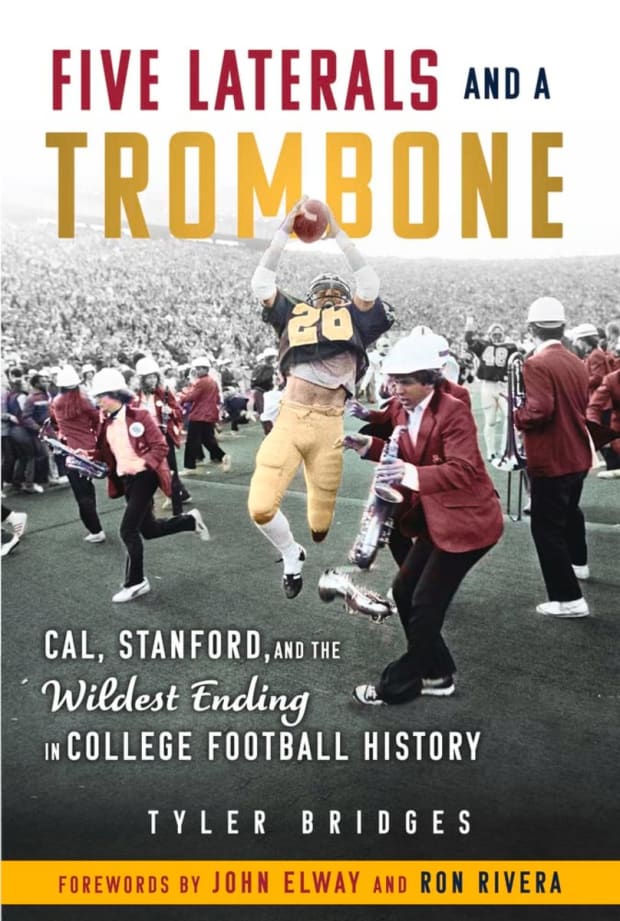

“Stuff this in yer trombone,” read the lead headline in Sunday’s San Jose Mercury News, above Robert Stinnett’s photo showing Kevin Moen’s euphoric leap in the end zone. The photo didn’t show what happened a split-second later—Moen bowling over trombone player Gary Tyrrell, who remained unknown that Sunday morning as he walked by the university’s Tresidder Memorial Student Union after attending Catholic Mass at Memorial Church. Uh-oh! Tyrrell thought when he saw the newspaper in the vending machine. He put in six quarters to buy two copies and then hurried back to his fraternity. Tyrrell figured he’d better lay low. Besides, as an industrial engineering major, he had plenty of homework. He hid out in the library for the rest of the day. Afterward, Tyrrell learned that reporters had been calling the Band Shak looking for him. He didn’t return any calls. He wanted the whole mess to blow over.

Fans, however, were having fun at the band’s expense. “That was the first time I ever saw a tuba player leading the interference on a touchdown—or on any other play,” a rooter told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It appeared to me that the weakest part of Stanford’s defense was the woodwinds.”

But others took the outcome as an opportunity to blast the band. “Over the seasons the Stanford band has offered more than a modicum of originality,” wrote Art Spander, the lead sports columnist for the Examiner. “The solo trumpet version of the national anthem was special. Many of the halftime shows were clever. Against USC a couple of seasons back, one musician carried an oversized report card depicting the subject matter and grades for the ‘typical’ Trojan football player. Good, clean fun is what they used to call it. Now, seemingly every stunt has a double entendre. They’ve become the ‘Animal House’ of music. At one game several members dropped their britches. One of the administrators should have given them a good spanking. Or the word that this sort of behavior is not only juvenile but stupid.”

Kevin Starr, a noted historian who had obtained a doctorate from Harvard and a master’s afterward from Cal, wrote a weekly column for the Examiner. To him, the Cal and Stanford bands represented a larger dynamic in society, with his view clearly reflecting his own up-from-the-bootstraps rise out of poverty. “The University of California at Berkeley marching band emanates an atmosphere of standards, seriousness, and respect for its audience,” Starr wrote.

Robert Stinnett

“Attired in traditional uniforms, the Cal band executes a series of musical and marching maneuvers that are the result of long hours of patient practice. In every way possible—the precision of its maneuvers, the selection and performance of its music, the demeanor of its membership, its high standards of conducting—the Cal band says to its audiences: we are university students who respect ourselves, respect Cal and the opportunities this great university offers, and most importantly we respect you, the people of California, whose taxes make this great university possible.

“The Stanford band, by contrast, each time its spells out an obscene word on the field with a certain disturbing pre-pubescent adolescent preoccupation, each time it performs music in a slipshod manner, each time, in short [to use a ’50s term] it RFs the public, communicates the exact opposite sort of message. The Stanford band says, in effect, we are the sons and daughters of Privilege, or at least we are aspiring to become the sons and daughters of Privilege, and we will therefore conduct ourselves as we think that the spoiled children of Privilege conduct themselves, with what we consider amusing brattiness.”

But not everyone turned on the band. Art Rosenbaum, the longtime sports editor of the Chronicle, and a columnist, wrote that he missed the final five-lateral extravaganza because he had set out for the Stanford locker room, sure they had won the game. “I empathize with the Stanford band,” Rosenbaum wrote. “I thought the game should have been over, too.”

That was Andy Geiger’s view as well. “Everybody thought the game was over except the officials,” said Stanford’s athletic director. “Hell, both teams were on the field; the Cal band was on the field, too. Why should our band be singled out? They showed an honest and exuberant excitement. Unfortunately, they had a premature celebration.”

That premature celebration, of course, was followed by a deep letdown, the lowest of lows at Stanford. And not just among the bandsmen. Members of the football team remained in the dumps on the day after the game. Two backups, Ken Orvick and Jim Clymer, were trying to ease their pain by downing cans of Coors Light at the Delta Tau Delta fraternity where they, Elway, and other football and baseball players lived. Orvick and Clymer agreed that the referees had robbed them of victory the day before. They had to do something spectacular in return. As they washed down the suds, Orvick and Clymer hatched a plan. They would grab a couple of teammates, drive across the bay, sneak into Memorial Stadium and cut the script Cal out of the Astroturf. They would drop it on the front porch at Paul Wiggin’s home as a form of war booty.

They thought it was a brilliant plan. Now all they needed were the necessary tools. Orvick, Clymer and the two teammates stopped at a Shell gas station on the Stanford campus and convinced the friendly attendant to lend them what they needed—knives, pliers and a saw. They set off for Berkeley. It was about 8:00 p.m, or a bit more than 24 hours after the defeat the day before.

The four parked near Memorial Stadium. One of the teammates stayed with the car. He would be the getaway driver. Orvick, Clymer, and Tom Nye, a backup guard, walked around the stadium.

It was cold, dark and rainy, and it seemed deserted. Perfect. They found a good spot and climbed over an eight-foot fence. So far, so good. The three walked into the stadium and looked around. No one was in sight. Approaching the Cal logo at midfield, they pulled out the knives, only to discover that the Astroturf had been glued to the slab of concrete underneath. Cutting through the turf was a bit like trying to cut through shoe leather with a butter knife. After a difficult half hour, they concluded that they couldn’t do it at all.

Well, the three hadn’t driven all the way to Berkeley to come away empty-handed. What could they do instead? Someone suggested they cut down the goalposts. Yeah, someone else agreed, that would be good revenge! They grabbed the tools, ran 50 yards, and began sawing the goalpost. They had cut in only one-eighth of an inch when the saw broke. Damn! What now? Still determined to do something, they climbed the stadium stairs to the press box. Maybe they could claim a souvenir from there. The door was locked. The hapless vandals were getting nowhere.

Then Orvick, Clymer and Nye heard a police walkie-talkie in the stadium concourse below. They had been spotted! Lying flat under the bleachers, they saw a police car drive onto the field.

They were wet and cold—and now their escapade seemed more hare-brained than brilliant. Plus, they faced the real possibility they’d be caught. But after a while, the coast seemed clear. They crept out of the stands, onto the concourse, and ran out an open gate to their car, hightailing it out of Berkeley. They wouldn’t be able to deliver the Cal logo to Coach Wiggin on his front porch after all.

As for the coach, the loss left him heartsick. More than anything else, Wiggin felt bad for his players. But he couldn’t do anything else. On the Wednesday after the game, he and his family flew east. His wife, Carolynn, was glad they had made plans to leave town for the Thanksgiving break. The change in scenery would do her husband good, she thought. Their destination was Williamsburg, Va., home to Colonial Williamsburg, a historic district and living-history museum where actors in period costume depicted daily Colonial life. The Wiggins wanted to show a corner of U.S. history to their daughters and a Spanish exchange student staying with them. The family was standing in line to enter a museum exhibit when the coach felt a tap on his broad shoulder. Wiggin turned around and saw a short man standing with his wife and two kids. “Are you the guy who coached the team that was beaten by that play?” he asked.

“Yes, I am,” Wiggin said, ever polite.

“I thought so!” said the man, turning to his family.

Wiggin turned back to Carolynn and muttered, “We can’t even come to a place like Williamsburg and get away from it.”

More College Football Coverage:

• After Tragedy, UVA Students Left With One Question: Why?

• Jimbo Fisher Shows Perils of Over-Investment

• CFP Rankings Reaction: The Good, Bad and Ugly