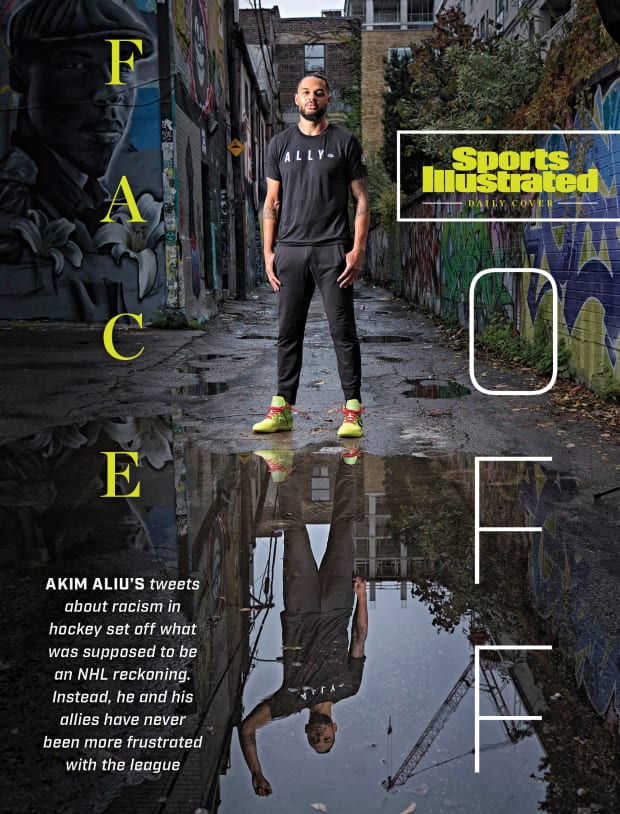

A group of current and former players led by Akim Aliu says the NHL is failing to address racism in hockey—so it’s up to them.

On Sept. 3, just past the midway point of the 2020 Stanley Cup playoffs, the NHL issued a 2,500-word press release cataloguing, as the headline declared, "Initiatives to Combat Racism and Accelerate its Inclusion Efforts."

It was a sensitive moment for the league. A week earlier, after police in Kenosha, Wis., shot a 29-year-old Black man named Jacob Blake seven times in the back, player-led protests in the NBA, WNBA, MLB and MLS spawned a night of unprecedented work stoppages. The NHL, meanwhile, had continued to hold games inside its Edmonton and Toronto bubbles, provoking outrage. “[T]he lack of action and acknowledgement from the @nhl [is] just straight up insulting,” tweeted Sharks winger Evander Kane, one of the league’s few Black players. The NHL finally went dark the next day, suspending play for two nights.

The release, then, offered the league a chance to show its commitment to a cause sweeping the world. Atop the list of initiatives, the NHL trumpeted the launch of a “first-of-its-kind” grassroots program for young skaters of color. Based in Toronto, the program would be run with the Hockey Diversity Alliance (HDA), a group of nine current and former NHL players cochaired by Kane and Akim Aliu, a 31-year-old former NHL defenseman who shook the sport in November 2019 by exposing his encounters with racism.

Just three months old, the HDA hadn’t been shy about raising a gym bag’s worth of stink about the NHL’s approach to social justice issues, both in public statements and on regular calls with league officials. But the conciliatory tone of the press release indicated a truce: “We appreciate the HDA’s input and will remain attentive to all of our Players’ concerns,” it said. “[W]e look forward to continuing the dialogue with the HDA, and working together to bring about the change in our game we both strive to achieve.”

Behind the scenes, though, the two sides’ relationship was closer to crumbling than continuing. According to multiple HDA sources, players were irked that they didn’t learn about the existence of this “first-of-its-kind” partnership until the previous day, when an NHL executive sought approval to use the group’s name in the release. HDA sources say the group asked to review the text’s wording, but the league refused. Requests for program details, such as how much funding the NHL planned to contribute, were also rebuffed, they say.

Only after the deadline was extended by a day and players were finally permitted a peek at the announcement, did the HDA vote to approve its role in the program. “Telling them, in good faith, ‘Use our name, make yourself look good, because the hockey world is watching,’ ” Aliu says.

The NHL disputes the group’s timeline: “The HDA was given at least two days to collaborate on the wording of the joint programming release,” says Kim Davis, the NHL’s diversity czar (and highest-ranking Black executive).

Either way, it was yet another example of the two sides’ struggling to see eye-to-eye. On Oct. 7, the HDA released a statement vowing to “operate separate and independent of the NHL,” accusing the league of “performative public relations efforts” that ignored “important conversations about race needed in the game.”

It is a dialogue Aliu has been seeking to advance ever since the Blackhawks’ second-round pick revealed on Twitter that his coach in the minors, Bill Peters, had “dropped the N-bomb” on him during the ’09–10 season “because he didn’t like my choice of music.” After the account was confirmed by several witnesses, Peters, who had gone on to become the Calgary head coach, resigned, apologizing publicly to the Flames, but not to Aliu.

Aliu hoped his revelations would spark a long overdue reckoning for the white-as-ice hockey world and its shut-up-and-stick-handle culture. Last season 18 Black players logged more than five games, according to the NHL’s count. Once this might have been viewed as incremental, if overdue, progress, with NHL teams’ icing a total of 18 Black players from 1917–18 to ’90–91. But consider that a Sports Illustrated feature from 1999 heralding a new generation of “hockey’s emerging [B]lack stars” projected that season would feature . . . 20 Black players. Since that year, the U.S. has grown far more diverse and the Black population of Canada has roughly doubled, to 1.2 million, according to the country’s 2016 census, its most recent. But the NHL largely looks the same.

As another season begins, Aliu believes the league is no closer to truly reckoning with its racial issues. And in the 14 months since his tweets, he’s grown more fed up than ever with the game that he continues to love, even if he hasn’t always felt that it loves him back. “It’s not hard to figure out our sport is suffering,” Aliu says. “Whatever the NHL is doing is clearly not working. It’s just posturing, window-washing, nonmeaningful half measures. That’s all it is.”

Early one evening in December 2019, as snowfall caked the Toronto area, Aliu (al-EE-you) wrapped up a workout at a Lifetime Fitness in Vaughan and drove to his favorite eatery, a no-frills, family-run pizzeria.

He settled into his customary table, back near the kitchen, where he wouldn’t be bothered, and ordered the usual: Greek salad, veal hoagie and penne dressed in what he dubbed “the best rosé sauce ever.” A month into his new life, he was still learning to handle all the attention. Lately, the restaurant owner, a friend, had taken to flipping the channel whenever Aliu became the subject.

“I’m still so mad that I can’t even watch,” Aliu said. “But it’s everywhere. It’s hard to cut off.”

It was far from what Aliu had expected when he sent his tweets. He’d been standing in the stairwell of that same Lifetime Fitness, reading about how just-ousted Toronto coach Mike Babcock—a mentor of Peters—had humiliated a former player, and decided to share his story: how Peters had slurred him, how he pushed back and then how he was demoted to a lower minor league. “First one to admit I rebelled against him. Wouldn’t you?” Aliu had posted. “Instead of remedying the situation, he wrote a letter to [management] to have me sent down . . .”

Supportive texts and calls had flooded his phone, many from fellow Black players

or other members of hockey’s underrepresented communities. But those were drowned by torrents of bigoted social media posts. He scrolled through a few he’d saved:

You’re a dumb f------ n------ that’s causing s--- because his feelings are hurt

All I see is some f---y ass p---y that wants to be in the spotlight

What a b---- I hope your family burns in hell

“I could probably show you another couple hundred of these,” Aliu said. “What I hear most is, ‘Why didn’t you come out 10 years ago?’ ” He paused, holding up his phone. “Well, this would’ve happened.”

Bigotry has been a constant presence in Aliu’s life. He was born in Nigeria to a white, Ukrainian mother and a Nigerian father; the family moved to Kiev when he was a baby. In one of his “most vivid” childhood memories, his mom was trying to hail a taxi for herself, Akim and his older brother, Edward. A cab driver slowed down just long enough to spew in Russian, “I’m not picking you up because you have two n------ with you,” before speeding off.

Seeking a more welcoming world for their sons, Tai and Larissa Aliu stuffed their belongings into a few suitcases and relocated to the Toronto suburb of Parkdale when Akim was eight. They rented a single upstairs bedroom in a stranger’s house and picked up multiple jobs each to make ends meet. Akim fell in love with the local pastime, saving up to buy a pair of used skates at a garage sale and practicing for hours by himself on area outdoor rinks. “I was in my sanctuary, man,” he says. “It was peaceful.”

Until it wasn’t. As he rocketed up the hockey ladder thanks to his slick skating, rugged frame and powerful shot, racism met Aliu at most every rung. After scoring 34 goals on a U-16 team with current Leafs captain John Tavares, Aliu, then a winger, went sixth in the 2005 OHL draft. On his first day with the Windsor (Ont.) Spitfires, 16-year-old Aliu went to meet some of his new teammates at the billet home of star forward and then recent Flyers draft pick Steve Downie. “Never seen him before in my life, but I looked up to him,” Aliu says of Downie, whose nine-year NHL career ended in 2016. “And the first thing he said when I walked in was, ‘What is this n----- doing in my house?’” Early that season, Aliu refused to take part in a team hazing ritual; later on, Downie cross-checked him in a practice and knocked out seven teeth. The pair then fought while teammates watched. (Downie could not be reached for comment despite multiple attempts.)

Six years later, in 2011, an equipment manager with the ECHL’s Colorado Eagles dressed as Aliu for a team Halloween party, arriving in blackface and a custom-printed Eagles jersey with Aliu’s longtime nickname, “Dreamer”—a nod to fellow Nigerian Hakeem Olajuwon—on the back. The experience caused Aliu such “terrible anxiety and insomnia” that he checked himself into the hospital for two days. “A dark, f----- up time,” he says.

Other racial barriers were subtler, like the high equipment costs and registration fees that his parents struggled to afford. “I don’t think I understood all the financial implications at that age,” Aliu says, “but you learn early that you’re different.” Even when he made his NHL debut for Calgary in April 2012, notching two goals and an assist in his first two games, the triumph came at a personal cost: At the season-long urging of an official of color in the Flames’ farm system, who had cautioned Aliu against “standing out” in a conformist sport, Aliu had shaved off his Afro prior to his call-up. “It wasn’t in a malicious way,” Aliu says of the official’s advice. “I just think he wanted the best for me and he knew how the system works.”

Much of this personal history spilled forth when Aliu visited the NHL’s Toronto office on Dec. 3, 2019, eight days after his tweets about Peters. Flanked by his new three-man legal team, Aliu met for an hour with commissioner Gary Bettman and deputy commissioner Bill Daly, who flew in from New York City just for the occasion. “I’m here to listen,” Aliu remembers Bettman telling him as the two parties sat down. “Whatever you have to say, say it.”

In addition to detailing the Peters incident for the NHL’s investigation, Aliu and his lawyers presented measures they wanted the NHL to enact, like a whistleblower hotline. Spurred by Aliu’s suggestion, an NHL spokesperson confirms, Bettman announced at a Board of Governors meeting the next week that the league would implement that exact idea (albeit without crediting Aliu). “One week I was just sitting around, trying to find a job,” Aliu says. “Then a week later I’m meeting with the commissioner of the NHL. Life comes at you fast.”

At the pizzeria, Aliu recalled a recent chat with his parents, who have long begged him to quit the sport after seeing its mental toll on him. “They were saying, your dream the whole time was to be an NHL superstar for 10 to 15 years, but now you might do more to change the game than you ever could’ve as a player,” Aliu said. “Obviously I’m not there yet, but hearing that is almost surreal. Hockey, out of all the major sports, needs the most retooling. Why can’t I be the guy that sparks that conversation?”

On Dec. 5, 2019, at 3:38 p.m., Aliu sent the first message in a text thread that he titled, Hockey Diversity Committee. Initially composed of about 10 NHL players of color, within two days the chat swelled to 20-plus, including All-Stars P.K. Subban and Seth Jones.

The goal: a safe space where members could share their experiences and create a unified force for change.

There was plenty to discuss. In the league’s 103-year existence, no team has employed a Black general manager. Only one Black head coach has stood behind an NHL bench—Dirk Graham, who led Chicago for 59 games in 1998–99 before getting fired—and, though records are spotty, it is believed that just two Black assistants have ever hoisted the Stanley Cup: Lightning video coach Nigel Kirwan (2004 and ’20) and goalie coach Frantz Jean (’20).

On-ice representation isn’t much more diverse. In addition to the 18 Black players who appeared in more than five games in 2019–20, the league counted just a handful more identifying as Asian (eight), Indigenous (six), Hispanic/Latino (four) or Arab/Middle Eastern (four).

“There’s that sense of loneliness we’ve all felt,” says Wild defenseman Matt Dumba, who is Filipino Canadian. “Who do you tell when you’re going through these things, besides your family? None of your teammates are going through it. And what am I going to say to a GM, an older white gentleman, who hasn’t seen the game the way I have?”

The forum that Aliu wanted, though, never materialized. Some players were spooked that he included his lawyers on calls and wondered whether he was trying to rally support for himself. “I think guys were concerned with Akim wanting to sue,” says Trevor Daley, a defenseman who recently retired after 16 years in the NHL. “I’m sure that crossed people’s minds,” says Aliu, who declined to discuss his legal plans. Other players voiced concerns about the career risk of speaking out. “There’s just so much unknown that comes along with that,” Dumba says. A few players dropped off the thread without explanation. “It was completely dead,” Aliu says.

When Aliu signed with a Czech club in January 2020—his 15th pro team in his sixth country since he last played in the NHL in ’13—it became even harder for him to keep in touch with NHL friends. By the time he returned to Toronto in early March, just as the COVID-19 outbreak was hitting North America, he worried that the momentum from his tweets was fading. But incident after incident proved that the conversation wasn’t going away. In January, AHL defenseman Brandon Manning was suspended for slurring a Black opponent; in April, the comment section of a fan chat with Rangers prospect K’Andre Miller was spammed with the n-word; in early May, Capitals forward Brendan Leipsic was waived after it became public that he made misogynistic comments in an Instagram message thread in which others hurled racist insults.

Seeking to reassert his voice, Aliu wrote a 4,000-word article for The Players’ Tribune on May 19 headlined "Hockey Is Not for Everyone"—a neck-high slap shot at the "Hockey Is for Everyone" diversity campaign that the NHL has run since 1998. The story described Peters’s comments, Downie’s cross-check and other instances of racial abuse in raw detail, prompting a viral response far more positive than what Aliu experienced after his tweets. Activist celebrities such as Alyssa Milano and Marshawn Lynch sent him direct messages, forming relationships that last to this day, Aliu says. So did several NHL players, with others expressing support in public posts.

Six days later a Minneapolis police officer knelt on the neck of George Floyd until the 46-year-old Black man died. Aliu marched in one Black Lives Matter protest in Toronto, stopping after out of COVID-19 concerns. But he was advocating action on a different front. The Zoom calls with fellow Black players had resumed, with a group of about 10 usually on the line. A common feeling emerged: Enough was enough. “All of our stories were basically the exact same,” says Daley. They decided to formally create an organization, with Aliu and Kane as its coheads.

In one of their earliest meetings, the (then unnamed) group welcomed a guest speaker whom Aliu had gotten to know through Ben Meiselas, one of his lawyers. Some were unsure what to expect when Colin Kaepernick appeared on their screens, but the quarterback spent two hours offering advice, impressing the group with his knowledge of the Colored Hockey League, an early-20th-century, all-Black outfit in Nova Scotia that, among other contributions, pioneered the technique of goalies playing the puck.

“Everything Kap said, I think we all held on to it pretty dearly,” says Dumba, one of seven founding executive committee members of the group, alongside Aliu, Kane, Daley and longtime NHL wingers Chris Stewart, Wayne Simmonds and Joel Ward. “But the unity of it all was really the strong message that I took away from it. Staying together as a group, not letting anyone else pull us in other directions. Strength in numbers.”

The Hockey Diversity Alliance officially launched June 8, with a press release posted to the individual social media accounts of its members. The group had no website, no Twitter presence, no specific initiatives—just a bold mission “to eradicate racism and intolerance in hockey,” focusing on community outreach and antiracism education. There was also a message for the NHL: “We are hopeful that we will work productively with the league to accomplish these important changes.”

In response, the NHL invited the HDA to spell out its objectives in a virtual meeting in late June with Bettman and Davis, who had been hired from a corporate advisory firm in 2017 to focus on diversity and inclusion. The players saw an opportunity to tell the commissioner about their encounters with racism in the sport.

Ward spoke about being bombarded with racist tweets from Bruins fans after his Game 7 overtime goal for Washington eliminated Boston from the 2012 playoffs. Simmonds discussed having a banana thrown at him by a fan during a 2011 exhibition. Daley recounted how his then Ontario Hockey League coach John Vanbiesbrouck called him the n-word in 2003. (Vanbiesbrouck resigned shortly thereafter, acknowledging the slur. He is now an executive for USA Hockey.) Kane described a fan yelling at him to go play basketball as he sat in the penalty box in Colorado during the 2019 playoffs. (Kane says he reported the incident to an on-ice official, but “there was zero follow-up” from the league. In the past, the NHL has said that the teams were aware, but the issue never reached the league office.)

As members began blasting Bettman for not doing more to prevent these incidents, the commissioner seemed to grow defensive. Citing various NHL diversity initiatives during his 27-year tenure, he then asked the players what they had done and where they had been in the fight against racism. He quickly backtracked, but the damage was done.

“I think he knew he had put his foot in his mouth,” Kane says. “Everyone on that call has done a lot of things on their own to grow the game within our own communities. A comment like that really rubbed guys the wrong way.” (Through a spokesperson, Bettman declined comment.)

On July 14, two weeks before the season restarted, the HDA presented Davis, Bettman and other league officials with a PowerPoint deck titled, Our Ask of the NHL. Much of the request focused on an eight-point “HDA pledge” that the coalition wanted the league to sign; items included specific hiring targets for Black personnel in league and team front offices (including 5% Black hockey-related personnel by the end of 2020–21) and funding of $100 million over the next decade (or just above $300,000 per team, per year) to back grassroots initiatives and other programming. The HDA also asked for various antiracism displays during the upcoming playoffs, such as changing the blue lines to black and painting the HDA logo on the ice. Kane recalls Davis and Bettman commending the presentation’s thoroughness. “I was hopeful,” Kane says.

But disappointment soon followed: The NHL built its postseason messaging campaign around a catch-all hashtag, #WeSkateFor, lumping the Black Lives Matter movement with the pandemic and other unrelated causes. “It’s like showing up to the breast cancer fundraiser and protesting that there’s other diseases, too,” Dumba says.

In public, the sides presented a united front. The HDA’s logo was displayed at times on video boards in the bubble, and Dumba delivered a speech about racial justice on reopening night in Edmonton, after which he became the first NHL player to kneel during the U.S. national anthem.

But the HDA’s frustrations were privately mounting. Among them: that the league asked Dumba to give his speech on just three days’ notice. And that while the league had agreed to help secure TV airtime for HDA ads in exchange for Dumba’s speaking, Kane says, nothing came of it. “They promised they’d have our logo on the JumboTrons throughout the tournament,” Kane says. “They only did it for the first week.” (The NHL insists Dumba was given six days and declined comment on Kane’s claims.)

Still, talks continued, largely thanks to a line change: After both sides agreed that their meetings were getting too “emotional,” as Davis puts it, players stopped attending and tagged in the HDA’s advisory board, consisting of Meiselas; Toronto lawyers Ted Frankel and Glen Lewis; financial advisor Chris George, an ex-Avalanche draft pick; and Rico Phillips, the OHL’s diversity and inclusion director.

The players continued to make their voices heard elsewhere. By the time of the Blake shooting, just one HDA member remained in either NHL playoff bubble: Colorado forward Nazem Kadri, who had joined the group in July. But the rest contributed from afar, serving as sounding boards for numerous white players who reached out with questions and helping advance the discussions inside the bubbles that led to the NHL’s two-day postponement.

The HDA also held Zoom calls with several teams on Aug. 28 to present a 20-minute deck that included basic info about the Black Lives Matter movement, stats on

incarceration rates among people of color, and videos of Floyd’s killing and Blake’s shooting. That same day Kadri, who is of Lebanese descent, joined dozens of players at a powerful press conference to explain their decision to sit.

“I think we have a unique opportunity to try to create sustainable change,” Kadri said.

In September, during one of the HDA’s calls with the NHL, the group’s advisers followed up about that “first-of-its-kind” grassroots program. Expecting the league to provide a rollout plan for the program, the HDA was upset to learn that it needed to create a plan itself and apply to the Industry Growth Fund, a joint NHL–NHL Players Association community relations program that had until then given money to only teams.

The league offered to help the HDA through the application, one HDA adviser says. According to an NHL spokesperson, “The NHL and NHLPA actually were taking an unprecedented step to mine the resources of a CBA-negotiated fund that had never been used for such a purpose before.” But where the NHL thought it was bending over backward, the HDA saw the league as barely moving a muscle. “It just seemed like a big game,” Kane says. “Why do we need to have this intense negotiation if, genuinely, you want to see this type of change?”

Then, on Sept. 11, the NHL sent what the HDA interpreted as an official response to its list of pledges. Titled "Hockey’s Commitment to Cultural Change," the two-page document proposed soliciting a host of potential signatories for an “actionable public commitment” toward “eradicat[ing] racism” in hockey, including every NHL team, Hockey Canada, USA Hockey, and various men’s and women’s pro leagues. But the text contained no hard hiring targets or specific funding commitments, only vague vows to, for instance, “further engage” people-of-color- and woman-owned businesses. To HDA players, this was evidence of an unbridgeable gap with the NHL.

Or, as Aliu puts it, “How long are you going to waste each other’s time before you call it quits?”

According to Davis, the HDA’s frustrations were news to the league. “We were shocked and disappointed that they decided that they did not want to continue the dialogue,” the NHL executive says. “We had been in constant conversation with them, working through what we thought were the details of a partnership.”

Asked to assess why talks ultimately crumbled, Davis points back across the aisle: “My sense is they wanted to control how we are executing our plan and weren’t willing to hear and understand that much of what they were requesting in the pledge were things that were underway, and that the best way to influence timing and accountability around that would be to work within the structure. . . . Partnership means that it’s a two-way street, both sides giving and getting a little. And I just felt like collaboration, from their definition, was pretty one-way.”

Under Davis, the league has been taking a slow-and-steady approach toward diversity. Rather than commit to the HDA’s hiring targets, the league commissioned a demographic study through the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. The whistleblower hotline finally became fully operational in December, a year after Bettman announced it, but not before what Davis calls a “comprehensive search” for an operator that settled on Deloitte. And while teams have been mandated to complete antiracism training, Davis says 100% participation isn’t expected until 2022, due to its cost ($500,000 for the league front office) and the economic uncertainty of the pandemic.

Rather than joining the HDA, several Black NHL players, including Subban, winger JT Brown (the first NHLer to protest during the national anthem, raising a fist in October 2017) and Vegas enforcer Ryan Reaves (the first player to decide to sit post-Blake), chose to work with the league on a series of inclusion committees. Their recommendations will be evaluated by an executive council codirected by Bettman and Sabres owner Kim Pegula, who is Korean. According to Davis, the NHL invited at least two HDA members onto each of these committees, which began meeting virtually in late October. The HDA declined.

Davis touts the intersectional diversity of the players, coaches, agents, media members and others on the NHL’s committees, which contrasts with the HDA’s lack of women and LGTBQ members. “We’ve got a coalition across all of the dimensions: race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation,” she says, later casting the HDA as “such a small body” relative to the league’s “47 active players of color.”

Asked by ESPN in October to compare the league’s efforts with those of the HDA’s, Subban took the historical approach. “I’m excited for the opportunity to work with the NHL, but there’s always going to be multiple people fighting that fight, multiple people trying to eradicate racism,” said Subban, who cochairs the player inclusion committee. “Everyone is going to have a different way, right? Malcolm X and Martin Luther King didn’t always see eye to eye, but they had an impact in their own right.”

HDA players take this view: The house is ablaze, and the league is off studying the best types of hoses. Or, in the case of some power brokers, ignoring the fire. In one meeting over the summer, according to multiple people present, Davis commented in passing that some NHL owners simply didn’t see racism as a pressing problem in hockey. The HDA members understood her to be illustrating the barriers to instant change, but they were still jarred. In another meeting later in the summer, multiple sources recall Davis’s relaying how several owners had reported losing season-ticket holders after Dumba’s bubble speech.

“Obviously we know as players what a lot of these owners are thinking,” Aliu says. “We were just shocked to hear it.”

The NHL had no comment on Davis’s statements.

Aliu concedes the validity of certain criticisms of the HDA, notably that it right now consists of nine men. “Not having any women, not having any Indigenous people, I think people need to understand that, number one, we are going to be doing that, and pretty quickly,” Aliu says. “We’re a new organization, so a lot of those things take time.”

But the HDA has thus far rejected the idea that it would be better served working within the NHL’s structure. To them, systemic change requires rattling cages. Like when Kane appeared on ESPN’s First Take in May to call out Sidney Crosby, among other NHL players, for not speaking out against racial injustice after Floyd’s death, leading to 128 players’ posting statements condemning racism on their respective social media accounts. (The league counted.)

“If we hadn’t been as aggressive on some stances as we were, no one would even know who the HDA is, or what we stand for,” Dumba says.

When news broke in October of the HDA’s schism with the NHL, Aliu was two days into a two-week quarantine at his parents’ house in Vaughan. He had been exposed to COVID-19 while training for Battle of the Blades, Canada’s figure skating version of Dancing with the Stars. Hotels couldn’t take him, so he isolated in the windowless basement, rolling back the rugs to make room for yoga mats, weights and his hockey equipment.

At first Aliu had resisted joining Battle of the Blades, fearful of “the stigma of being on a reality TV show” as an active player looking to find another team for his 13th pro season. But he was swayed by his girlfriend and parents, who emphasized both the potential financial benefits and the national reach of the program’s weekly prime-time TV slot. Competing with his partner, 2019 European pairs champ Vanessa James, they formed the show’s first-ever Black couple, finishing fourth and winning $25,000 for Aliu’s Time to Dream Foundation. “The show is all about sharing your message,” Aliu says. “So I just thought that was important, for the country to see what I’m doing.”

Aliu remains steadfast that he should be playing in the NHL, that he was branded uncoachable after the Peters incident and “essentially blackballed.” He notes that four men who worked in the ’10–11 Blackhawks’ front office were NHL GMs last season. “Hockey’s a small circle,” he says. “Once you get labeled something, especially if you’re somebody of color, it doesn’t matter how good you are.”

Asked what he hopes to come from the NHL’s investigation into his case, which the league says is ongoing, Aliu doesn’t hesitate: “the truth about why I wasn’t able to be successful in the National Hockey League,” he says.

For all of his bitterness toward the NHL, though, Aliu believes the HDA is fulfilling its mission. He points to the recent team hires of three group members—Ward (Las Vegas), Daley (Pittsburgh) and Stewart (Philadelphia)—and that of Florida’s Brett Peterson as the league’s first Black assistant GM. He describes “great conversations” with reps from the NBA’s Cavaliers about potentially building a joint basketball-hockey youth program in the Cleveland area.

With newfound corporate support providing a push for social justice efforts across all sports, the coalition has also partnered with several NHL sponsors, Aliu says, including Sportsnet (to produce antiracism education videos) and Kraft Heinz and Scotiabank (to build youth programs in Toronto, with Pittsburgh and Vancouver targeted next). “We’re showing the NHL that everybody’s on board to do the right thing, including their partners,” Aliu says.

The league is similarly forging ahead on the youth hockey front, with plans in Pittsburgh for a program to develop skaters of color. Run by the Penguins, it is slated to be named after Willie O’Ree, the NHL’s first Black player, and will ideally serve as a model for other teams in the future, Davis says.

If the HDA’s and NHL’s pilot programs meet success and the efforts expand, a bizarre scenario is possible: dueling grassroots programs run by each group in the same cities, funded by the same sponsors, with the same goals. “Being realistic, there’s things that we can’t do without the NHL, and there’s things the NHL can’t do without us,” Aliu says. “Us being in a quarrel is not positive for either side.”

For now, though, Aliu and his fellow HDA members will keep fighting, at once together and alone.