Meltdowns and missed chances at the Masters continue to haunt some golfers at Augusta National.

AUGUSTA, Ga. – Rory McIlroy hit a practice putt here Tuesday, as Bernhard Langer was walking across the green, and Langer stopped and let McIlroy’s ball pass. That was nice. It would have been nicer if Langer had picked up McIlroy’s ball and talked to it.

Langer knows what McIlroy has yet to figure out: how to play his best golf at Augusta National during Masters week. Langer is a two-time Masters champion who has somehow made the cut three straight times after turning 60. Put him at Baltusrol for a U.S. Open, and Langer would have no shot. But Langer knows how to navigate the quirky contours of Augusta National, and just as important: He knows that he knows. He plays the course with the quiet confidence of somebody who has the answers.

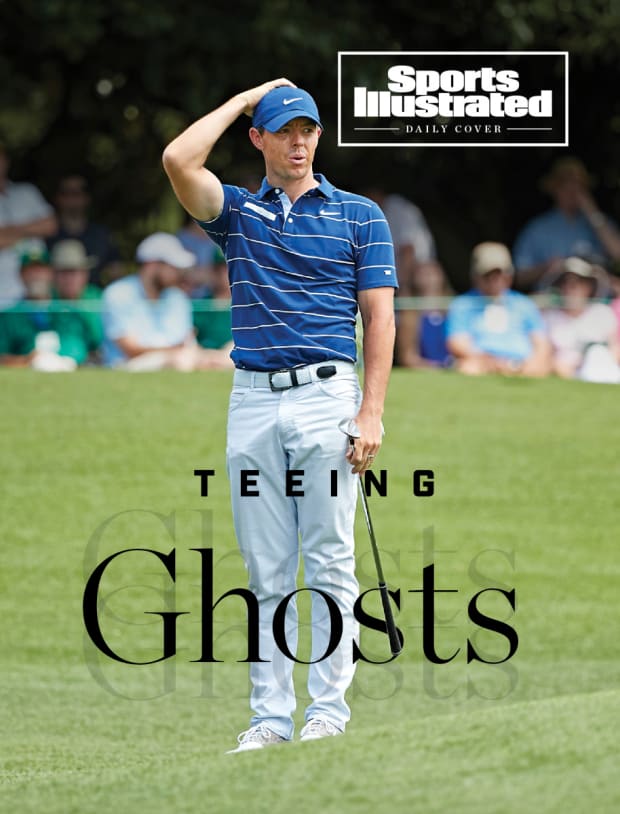

Meanwhile, Augusta National has messed with McIlroy’s head so much, he might as well arrive in a basket. Ever since he stood on the 10th tee in 2011 with the lead, then pulled his tee shot into South Carolina, the place has haunted him. He has actually played very well, except when the tournament is on the line. He either takes himself out of it early, then plays great, or plays great, then takes himself out of it.

“I've played a bunch of really good rounds on this golf course before, but just not four in a row,” McIlroy said this week. “That's the challenge for me.”

Because he has been so good, so likable and so close, McIlroy is the most obvious current player fighting Masters ghosts. But he is not alone. There will be two kinds of golfers at the Masters this week: those who know how to win here, and those who tell themselves they do. Everybody is desperate to be in that first group, which is why so few are in it.

The current generation of golf stars is openly obsessed with the Masters. They grew up watching Tiger Woods win here and hearing about “a tradition unlike any other.” Some of the best Europeans, like McIlroy, live in the United States. Two generations ago, one could reasonably argue that the British or U.S. Open was the most important in the world; you could argue that today, but good luck getting a player to agree with you.

“I’m doing the same preparation that I do in other majors,” says Justin Thomas, who is on the short list of favorites this week. “And it's just, you know, for some reason, everybody wants to win it a little bit more, and I definitely got sucked into that. … [I] want to win so bad. I feel like this place is so good for me. Like, ‘Dude, O.K., I get it, you like this place.’ You can only control where you are at that moment and hit that next shot exactly where you want to hit it, and if it isn't, you go and you hit that one from where it is next.”

The problem for players—and the fun for viewers—is that on its best day, Augusta National requires constant mental adjustments and a level of decision-making most courses don’t demand. Misjudge an angle and you could make double bogey. Get too aggressive on the wrong hole at the wrong time, and there goes your week. But get too conservative, and the field could run away from you.

Augusta National is the one course that hosts a men’s major every year, yet it is still full of mysteries. Some players have an innate ability to see the course and figure out how to play it. There is a reason that Jack Nicklaus showed up at 46, presumably washed up, and won; or that Tiger Woods has won his only post-comeback major at Augusta; or that Jordan Spieth seems to play well at the Masters even when he is playing poorly everywhere else. They were all brilliant at assessing the right approach to each hole on each day and then executing it.

It also helped Nicklaus, Woods and Spieth that they all won the Masters early in their careers. You can easily watch a player at the PGA Championship and have no recollection of whether he has won the event before. But Augusta National constantly reminds you of who has triumphed. Winners can wear green jackets on the grounds whenever they return. They (and only they) go to the Champions Dinner on Tuesday night. They get invited back for as long as they can reasonably get around the course without embarrassing themselves.

Spieth needs to win the PGA for the career grand slam. McIlroy needs the Masters. McIlroy has clearly been more obsessed with his missing piece. He is open enough to admit it and charming enough to laugh about it.

“I think if I contrast my few weeks leading into the 2015 Masters, coming off the summer in 2014 and going for the Grand Slam and my third major in a row and all that, it feels a little more relaxed this week,” he says.

The unique challenges of Augusta can be seen through the eyes of some of the top players. McIlroy has to put aside his history here—not just the 2011 meltdown, but the 2018 debacle, when he tried to put the pressure on Patrick Reed on Saturday night, then played poorly Sunday while Reed blew him away.

Thomas has to apply the skills he developed after rising to world No. 1 in 2018. He has always had a knack for getting hot—bombing his driver and shooting a low score for a day—but he is a more complete player now. He is creative and deft around the greens. He can squeeze a 71 out of a day when he isn’t striking the ball very well. As long as he stays patient, Thomas should contend here quite a bit. He also does not have the scars that McIlroy has. Thomas said this week that he believes he will win the Masters and can do so more than once. McIlroy is unlikely to put two mountains in front of himself like that.

Spieth arrives having rediscovered his game. He just won for the first time in nearly four years, and it wasn’t surprising—he battled a two-way miss and putting woes in recent years, but he has played as well as anybody in the last few months. Spieth has his own Masters ghosts—a meltdown at No. 12 in 2016, which cost him a second straight green jacket—but he loves it here and it shows. Even last November, before he started playing well, he seemed especially happy and confident leading into the tournament.

Bryson DeChambeau is perhaps the most fascinating star this week. He hits it so long, and putts so well, that he understandably believes the course is set up for him. But is it? DeChambeau excels on long courses with tight fairways and thick rough—that way, everybody must hit out of the rough, but he can do so with shorter clubs because he hits it so far. This week, Augusta National is playing firm and fast, with much lower rough than there was last November. That means errant drives will end up in trees.

The 2020 U.S. Open champ also has an extremely unusual decision-making process—DeChambeau does a bunch of math in his head, calculates what he should do and does it. It’s something most players could not even try, but it works for him. The question is how well it works at Augusta National. Part of what makes the course so interesting is that there are almost no flat lies. Last year, DeChambeau miscalculated when the ball was above his feet on the par-5 13th, and it ruined his round. He compounded the problem by going for it again. He made a double-bogey seven.

DeChambeau prides himself on being aggressive in most situations, figuring the math supports him, and he can be stubborn in the heat of competition. Augusta National punishes players with that mentality. DeChambeau is so good that he is capable of adjusting, but he might need a few years of suffering before he does—and then, like McIlroy, he would have to block out some bad memories.

Maybe Dustin Johnson is so buoyed by his November win that this Masters will be low-pressure for him. Maybe Brooks Koepka has enough majors confidence and Augusta knowledge to find his way into contention, three weeks after knee surgery.

This much is clear: Whoever wins the Masters cannot be spooked by trying to win the Masters.

“Maybe late Saturday and on Sunday is when you could and can start changing your game plan or changing your mentality on the course, if you need or have to make something happen,” Thomas says. “But it's still golf. It's a major. It's the Masters. Everybody wants to win it, but it's still golf.”