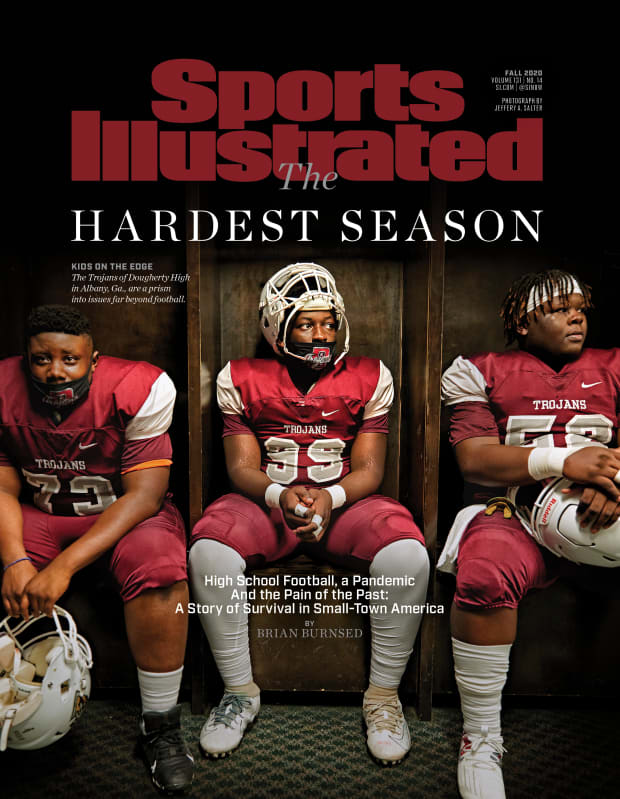

High school football, a pandemic and the pain of the past: A story of survival in small-town America

Ju-Marcus King cracked open the door to his grandfather’s room in the house they share, peering with wide eyes over a fabric mask. Jeff King lay in bed on March 31, a fever boiling inside him, as Ju-Marcus, a 16-year-old high school freshman, dutifully delivered water to the man he calls Daddy.

At the hospital four days earlier, doctors said they believed Jeff’s fever had been triggered by kidney stones, but out of an abundance of caution they ordered him to isolate from his family inside his tiny, taupe, concrete-block home with crumbling steps and a dusty front yard. The new virus—the one splashed across the news; the one spreading across the globe—had made its way to Albany, Ga., a deteriorating city three hours south of Atlanta, dotted with church steeples and encircled by vast pecan orchards and cotton fields.

Ju-Marcus, his gentle voice muffled, asked his grandfather how he felt. “I’m all right,” said Jeff, 69 years old and nearly 300 pounds, trying to project calm to the boy he had helped raise ever since his own daughter Victoria, the youngest of Jeff’s 16 children, brought the child home when she was 23. Jeff had been the one who ferried Ju-Marcus to pre-K in his white pickup—the one they called Space Ghost—and later drove him to football practice at Dougherty High, where the six-foot, 250-pound backup defensive lineman clung to outsize dreams of one day playing for Alabama, LSU, Florida State . . . somewhere else. Anywhere else.

“I’m all right. . . . I’m all right. . . .” Jeff whispered to Ju-Marcus, as if trying to will fiction into fact. For decades Jeff had been a respected mechanic in Albany—even if he was asked sometimes to don fresh clothes when he worked on cars belonging to wealthy (usually white) patrons—but a hernia had long ago forced him to retire. When one of his children finally called a doctor on March 31 and an ambulance arrived, EMTs had to maneuver a stretcher through a collection of cars that had fallen into disrepair on the dirt patch out front. Jeff ultimately summoned the strength to walk out of his room on his own, past his 67-year-old wife, Jimmie, who herself had recently fallen ill. Her heart was failing, and . . . something else.

Jimmie watched helplessly as her partner of 53 years finally sank into the stretcher. “Baby, I need you,” she sobbed as EMTs hauled him away. Then again, softer: “Baby, I need you.”

Ju-Marcus went over to the slight woman with the white tuft of hair, one of his life’s few constants. Jeff was tall and strong; he had been the foundation who held up the vast King family through unrelenting hardship. “Don’t worry,” Ju-Marcus assured Jimmie as the ambulance sped off. “Daddy’s going to be home shortly.”

***

The virus that doctors found to have infected Jeff King’s lungs—and, more crucially, infiltrated the region that his family has called home for generation after generation—was destined to touch Albany, as it has almost everywhere else, but perhaps nowhere was the disease more likely to thrive than in this community of 72,000. Throughout the world, COVID-19 has inflicted its worst on populations where access to health care is limited, and where poverty, obesity, diabetes, hypertension and respiratory issues abound. In Albany, the prevalence of those ailments is inextricably tied to the region’s history. Being Black and poor in the deep South, inheriting burdens fostered by longstanding inequities, appears to be the most hazardous comorbidity of all.

Health officials believe the coronavirus first began to spread across Georgia’s 12th-largest city last February or March, starting at a pair of funerals in the Black community. By April, Dougherty County—despite being carpeted with farmland and situated 40 miles from the nearest interstate—had the second-highest per-capita COVID-19 case volume in the country, behind only New York City (and not far behind Wuhan, China, where the virus originated). And while roughly 70% of the county’s population is Black, that subset accounted for about 85% of Dougherty’s total hospitalizations and deaths at the peak of infection, from March through May.

If those funerals were the match that led the coronavirus to engulf Albany, history was the kindling. After historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois visited in 1898 he remarked that Albany lay in “the heart of the Black Belt,” evoking the crescent of fertile land that cuts through several Southern states, where enslaved people were put to brutal labor at cotton plantations that thrived in the 19th century. As Du Bois toured the remnants of antebellum Albany, one Black local told him, “This land was a little hell.”

More than a century later, slavery’s lasting effects are evident on any map depicting Black populations in the rural South. Dougherty County is no exception: Nearly 30% of residents live in poverty; 14% are diabetic; 17% are uninsured—all rates that eclipse state and national averages.

In the wake of slavery, sharecropping and segregation, plus a downturn in manufacturing after I-75 bypassed the city, many Black families in Dougherty County are now crammed three or four generations deep into meager one-story homes, creating lush breeding grounds for any virus. “Socioeconomic disparities and racial differences are nothing new to us; that’s life [in Albany],” says James Black. And he would know. In 2006, Black returned from a medical residency in Florida to care for his community; now he oversees the emergency department at Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital, where he was born. This spring he watched as entire families were wiped out in the ICU, one patient’s eyes dropping to the floor, his shoulders slumping, resigned to his fate, when he learned he would have to be intubated, just like the wife he’d buried days earlier.

Du Bois long ago observed that northwestern Albany was whiter and wealthier than the rest of the county, and those delineations still stand. The city is bifurcated by the Flint River, on which cotton was long ago shuttled, and the eastern shore has persistently been more destitute. That is where the coronavirus flourished.

Dougherty High lies three miles east of the Flint, between a drab apartment complex and a ramshackle inn, and nearly all of its faculty and 1,100 students have felt COVID-19’s sting in one way or another. The county’s schools closed on March 13, and sports were canceled two weeks later, leaving educators and coaches alike to stare down the specter of a lost semester, a lost season, and wonder what harm it might do to boys like Ju-Marcus. Boys who were stuck inside as relatives and neighbors fell ill or perished. Boys who ached for a structure and direction that, for them, does not often exist outside of tidy white lines painted on football fields.

So, with the immense weight of both the past and the pandemic pressing against them, as summer yielded to fall, a school and its football team began to push back, striving to find tiny victories amid incalculable loss.

***

Nearly three months after Jeff King’s ambulance ride, while many of Albany’s streets stayed quiet, Dougherty High’s football players reconvened for the first time since their lives had been upended, on a practice field that abuts their school. They were permitted at first to work out only in groups of 15, spread out, as their bodies reacclimated to exertion under the southwest Georgia sun. They couldn’t touch footballs, weights or equipment; water fountains were off limits.

Coach Johnny Gilbert made certain that extra water bottles were on hand, and afterward he watched as his players, having spent months inside, lingered and bantered. “They needed to get a mental break,” he says. “Coach, I just need to get away.”

Gilbert, 50, knows the feeling. Born into a three-generation, 12-person home in south Albany, he would rise early as a teen to chop firewood for the family furnace, then escaped toward school and football practice. In his grandparents he saw the limited future his hometown offered: His maternal grandmother, Minnie, had nine children, and her husband, Turner, worked at a Firestone factory until it was replaced in the 1980s by a Cooper Tire plant, which itself shuttered in 2009 as the Great Recession squeezed the region. (In one recent analysis of recovery from that financial crisis, Albany ranked 487th out of 505 metro areas across the U.S. From ’08 to ’18, the city lost 3.7% of its GDP, and its population has fallen 7% over the past decade.) If I can ever get a football scholarship and finish college and find a job, Gilbert remembers thinking, I ain’t cutting no more wood.

He chased that dream first in the backyard, then at nearby Monroe High, where in 1987 he quarterbacked the team to the state playoffs for the first time in more than two decades. A scholarship at Albany State led to a college degree (the first in his family), which led to a coaching job, which led to the new house he built for Minnie in Albany, replete with central air and heating.

It wasn’t until 2019, when Gilbert was living a few hours away in the Atlanta suburbs with his wife and two children, that he felt the pull back home. Eddie Johnson, then the sixth Dougherty High principal in as many years, at a school that was 90% Black and where many students saw the world only through poverty’s prism, wanted to turn around a team that had gone winless a year earlier, so he reached out to a local legend with deep roots in the community. His pitch had little to do with football. “We need you,” Gilbert recalls him saying. “We need someone who can relate to these kids.”

Gilbert took the job at Dougherty High and left his family in the ’burbs, commuting back on weekends. (Minnie had by then died. Her grandson moved into the house he’d built for her.) The new coach arrived to find a school that reflected East Albany’s history: dwindling enrollment. Rebounding but still substandard academic metrics. And a student body that, squeezed by food insecurity, relied on free or reduced-cost lunches. “The kids’ minds are filled with things like, Where am I going to stay tonight? Am I going to have food when I get home?” says Dougherty County superintendent Kenneth Dyer. “They can’t concentrate in class, so we try to reduce those nonacademic barriers.”

Gilbert’s main goal, then, has not been to implement some high-powered offense or to push the Trojans to a winning record, but to cultivate discipline among his players. Show up early. Pick up after yourself. Hold your teammates accountable. Coaches provide rides home from practice. They field text messages and phone calls at all hours, from players and from parents, rarely to talk football. Dougherty High, a Class 4A team, finished 2–8 last year, but Gilbert saw more wins than losses. “I’d rather build them into men,” he says. “To be good fathers. Good husbands. Good neighbors.”

More than 80 of those players were expected to show up for spring practice. Then COVID-19 descended. By the time conditioning resumed, in June, the roster had dwindled to 55. Parents—particularly those with mothers and fathers of their own living under the same roof—held kids out, fearing what they might bring home. Players worried they would spend the summer running sprints in the heat with little chance of spending fall Fridays bathed in stadium light.

Coaches, meanwhile, did their best to manage these concerns while fighting the effects of the virus in their own homes. Receivers coach Grady Vance lost an uncle and a cousin, and months later he still catches himself wondering whether he should be worried about his sore throat, or about how winded he got climbing a flight of stairs. Janell Jones, who helps oversee the passing game, stayed away from his daughter for three months. Running backs coach O.J. Martin, too, avoided his son, who’s three and has a weakened immune system, receiving only a “Hi, Daddy!” through the window when he dropped off sanitized groceries. Kenyan Conner, the offensive line coach, watched a fraternity brother go to the hospital on a Tuesday and die that Thursday.

“I haven’t hugged my momma since this stuff [started],” says the team’s defensive coordinator, Roderick Moore. “I wouldn’t be able to take it if I gave [the virus] to her.”

In early July, players were finally allowed to enter the weight room—but just as it seemed the Trojans were inching toward a season, and some sense of normalcy, the county’s case load spiked, attributed in part to Fourth of July gatherings. On Aug. 11, Dyer announced that fall sports would be delayed; he would circle back in September with a decision on the season. And just like that, hope seemed lost. “It’s hard to keep them motivated in the hot sun, doing all that work,” says Bryan Brown, the linebackers coach, “when the season can be gone in a minute.”

The team suffered a more serious setback on the same day as Dyer’s announcement—only no one realized it at first. A thunderstorm forced practice indoors, and when the district athletic director learned that 50-plus players and coaches had all crammed into one gym, against county guidelines—according to coaches, the plan had been to send half the team to a middle school facility, but they were denied access, so they audibled—practice was canceled for the rest of the week. But the damage was already done.

Moore was coughing nonstop when he reported to work three days later and Gilbert, panicked, sent him home. By the time the coordinator visited an urgent care center for a test, his fever had reached 102˚. For three days he lay in bed with a cold towel across his burning forehead, his body aching, his breath labored. “Worst three nights of my life,” he says. “I wouldn’t wish it on nobody.”

Every assistant was tested immediately, but only defensive backs coach Joseph Stone came back positive. He quarantined at his house with symptoms that mirrored Moore’s, and after nearly a week his fever finally broke. The Trojans were sent home for two weeks. “The fear sets in,” says Johnson, the principal. “You start thinking, Oh, my God, is it going to run through the team?”

No players ultimately displayed any symptoms, and no word trickled back to Gilbert about parents or grandparents who had suddenly fallen ill. With no mandatory testing for students, coaching, like so much else in 2020, was reduced to regular video calls, during which players, now in close quarters with their families, were warned to stay away from friends and parties.

Those virtual gatherings became the place, too, where coaches did their best to help players (all but one of whom are Black) navigate the national conversation about race and police brutality, after the May 25 police killing of George Floyd, while steering them away from confronting police—or anyone else who might provoke them.

The racial animus that Du Bois long ago observed in Dougherty County—back when white citizens were complaining about Black crime and Black citizens were jailed in droves, so they could be exploited for physical labor—had remained apparent through the ’60s, when a civil rights coalition called the Albany Movement fought segregation and reported to federal authorities more than 100 instances of police brutality. None of those reports yielded indictments, but half a century later W. Frank Wilson, who until recently ran the city’s civil rights institute (and who himself spent six weeks in a hospital with COVID-19), says he finally sees signs of progress. In 2004, Albany elected its first Black mayor. And today, five of the seven county school board members are Black.

Still, in the sprawling Oakview Cemetery in downtown Albany, just west of the Flint, dozens of small confederate flags still billow in the wind on crisp fall days, defiantly marking the graves of those who long ago fought to keep Dougherty County’s Black population in chains.

***

Kameron Davis’s roots in Albany run at least four generations deep, yet he yearns to rip his family up from that familiar brown, sandy soil. Even in a two-parent, two-income household, money is a constant worry. He hopes his athletic prowess, exceptional for a 14-year-old, might someday yield an escape. “I want to move,” he says. “Get my whole family out, because everything is getting tough. Seeing a lot of people die.”

Only a freshman at Dougherty High, Kameron could easily pass for much older, with his deep voice and granite shoulders. He hit leadoff for the gold-medal-winning U.S. U-12 baseball team at the Pan American Championships in 2018, and earlier this year, after eschewing loads of other interested schools, he was tabbed by Gilbert as Dougherty’s starting quarterback—a dual threat with a center fielder’s zip on his passes and the straight-line speed to burn past edge defenders. His parents, Dianna (a customer service rep at Walmart) and Roosevelt (a maintenance worker at Albany’s Marine base), long ago immersed their two sons in sports as a way to shield them in a city where the violent-crime rate is three times the state average. Where, in 2010, Dianna’s father, largely absent in her life, was clubbed to death with a metal pipe. Where, in October, the younger brother of one of Kameron’s teammates was shot and killed.

Kameron’s escape route, however, was cut off this summer, and in early September he fretted about his 56-year-old grandmother, Claudia Dawson—the woman whose house he would pop by so often to lend a hand as she baked the pound cake he loved. Dianna, having already seen several family members afflicted, was alarmed in August to hear her mother sniffling over the phone, and when Dawson came back with a positive test result, she, too, was ordered to quarantine. Kameron made the short walk to see his grandmother when he could, sitting on the porch outside her front door, conversing through the screen. Eventually, the young quarterback confided in his coach: I’m scared.

This was around the same time that Dougherty’s kicker, Miguel Vargas—a second-generation Mexican American and the only non-Black Trojan—caught the virus from an infected aunt. The 16-year-old junior lost his sense of taste and smell; lethargy and a frightening fever soon followed. His mother, Maria, a house cleaner, weighed her options: visit the hospital, with all the hassle that would bring, or fight it alone, at home. She chose the latter, and gradually the symptoms faded. Back on the practice field Miguel felt fatigued, and changed by this unexpected glimpse of his own mortality. With teammates, though, he felt a newfound camaraderie. “They understand that being on the field is a privilege,” Miguel says. “A blessing.”

For the most part, high school football in Georgia kicked off on Sept. 2, and across the state classes resumed, but Dougherty County held out. The fate of the Trojans’ season remained uncertain. Dyer, already wary after the Fourth of July spike, first wanted to see how Labor Day might impact the county.

When it didn’t—when data showed that the average county case rate had fallen to 5.1 per day, with only 4.8% of tests coming back positive—Dyer finally decided: Fall sports could start up. Dougherty would host Turner County High on the night of Oct. 2, giving the Trojans little more than two weeks in pads to prepare for the rigors of full-speed competition. At least now they were facing an opponent they could see.

***

Jeff King spent three months in a coma, a machine breathing for him, as his body contended with a virus that to this day has taken more than 1.3 million lives across the globe. Only when he finally awoke, midsummer, at a hospital in Rome, Ga., did Ju-Marcus’s mom, Victoria, reveal to Jimmie just how close she’d been to losing her husband. (Jimmie, too, had contracted COVID-19, but she weathered through the worst of it, even if it left her often winded, her memory flitting in and out as she wondered where her husband had gone.)

The King family, in those months, had been ravaged. Victoria’s godfather died, as did Jeff’s older sister and a cousin. The funerals were livestreamed, with grave-side crowds limited to 10 people. “It’s death after death after death,” says Victoria. “One little song, one prayer and get out the way.”

Through it all Victoria saw her son retreat further inside himself. Ju-Marcus, like his grandfather, takes pride in staying solemn through any circumstance, but the concern in his eyes betrayed him. To help his mother, whose body had been racked by two violent car crashes, and to avoid bringing the virus home, he stayed away from football through the early parts of summer. He moved into Victoria’s apartment, doing his best to maintain his workout regimen (and largely failing, as he packed on pounds). He dutifully kept up with his virtual schoolwork using his mother’s steady internet connection and fought to meet her exacting standards as he crashed at her home. “I want him to go above what I did,” says Victoria, whose injuries have kept her away from work since 2011.

Once Jeff woke, Victoria spoke on FaceTime with her still-intubated father, who blinked to let her know he could hear her. Later, as the elder King’s speech returned, he questioned Ju-Marcus over the phone about how he was getting to practice without his granddad’s rides. (Moore and defensive line coach Montavious Stanley had picked up that slack, and Gilbert checked in often.) In August, after months away from conditioning, Ju-Marcus returned to practice and started sloughing off the extra weight, striving for the scholarship offers that he’s still certain are coming.

Finally, on Sept. 29, after nearly six months of being shuttled between hospitals across the state, and just three days before Dougherty High’s first game, Jeff King came home. He returned as he left, on wheels, his body now battered by the virus. But there was Jimmie, who’d spent months in the care of family, waiting for him. “I cried many nights for him to come home,” she says.

A physical therapist came to the house the next day and helped the now 70-year-old patriarch take his first steps in the better part of a year, but therapy alone won’t suffice. The Kings don’t have the money for a home health aide—someone to bathe Jeff, feed him, help him to the bathroom. They need a ramp to cover those crumbling front steps, but they can’t afford that either. Medicare and Medicaid will put a dent in all of this, but Victoria says her father’s hospital stay has placed a tremendous strain on an already strained family.

“People don’t understand: Poor people go through a lot,” says Jimmie’s sister, Loretta Thomas. “Trying to get [the house] up to standards and keep it clean enough for [Jeff] not to get sick again is a lot of work. And we don’t get the help we need.”

Church friends stopped by, offering whatever they could—some juice and Captain D’s takeout—and once Jeff was settled, Ju-Marcus came by to see him. They talked for two hours, laughing about old memories, like that old white truck, Space Ghost, and eventually they hugged, leaving Ju-Marcus feeling like “a little child again.” But not for long. He hopes to move back in with Daddy and Ma, to repay them for those memories. “He has a lot on his plate,” says Thomas. “He don’t get to live the life of a young man.”

Before Ju-Marcus left, Jeff (who would be hospitalized again in October with a weak heart) asked his grandson whether he was starting or still on the bench this year.

“Starting, Daddy.”

Jeff nodded and said he expected to see him on the news that Friday night.

“You gonna see me, Daddy.”

Neither man shed a tear.

***

A few hours before each game last season, the Trojans would gather at a church for some food and spiritual nourishment. But with Black sanctuaries in Albany still mostly shuttered—while white ones in wealthier areas, having suffered disproportionately less, have largely begun to reopen—the team instead assembled at a field house near the high school before its long-anticipated opener. One player’s mother owns a food truck, and she fed the kids baked chicken, green beans and rice in Styrofoam containers before everyone piled into one of three buses for the 11-minute ride to Hugh Mills Stadium, just north of downtown.

On their way, they rolled by strip malls pocked with abandoned storefronts, across the Flint River and under the canopy of timeworn trees draped in Spanish moss. The stadium—dug deep into the ground and ringed by a stark concrete wall topped with barbwire—is a foreboding venue, weathered and worn, but a glimpse inside revealed tidy hedges and a crisp, new playing surface, all of it glowing under LED lights.

Lea Henry, the district athletic director (and a former basketball standout at Tennessee, under Pat Summitt), had herself contracted a mild case of COVID-19 in the summer, and she thereafter set about ensuring that high school football fans wouldn’t run the risk of suffering the same simply by attending a game. Masks were mandatory at Hugh Mills. There were digital tickets and temperature checks and sanitizer stations and signs imploring fans to sit a row apart. Capacity at the 11,500-seat venue was limited to 2,400, but the turnstiles revealed a wariness. Only 869 fans showed up.

Among them: Kameron’s family, including Dawson, who huddled in the center of the bleachers to watch the heralded teenager’s first start. (After two weeks in isolation she had tested negative, and Kameron finally reentered her home for a hug and a whiff of her oven.) Not among them: Ju-Marcus’s family. Victoria felt only trepidation about football, given all that the Kings had endured. “The virus is still real active; it’s still out there,” she says. “I’m nervous every time he leaves the house.”

Before kickoff, 60-odd Trojans coaches and players in maroon uniforms and sharp white helmets crammed into a musty, poorly ventilated locker room underneath the east side of the stadium, in what could easily be seen as a perfect incubator for the virus. A serious risk traded for a moment of togetherness, which Gilbert milked for positivity. “I told you four weeks ago that they ain’t going to play no football without us,” he told his team. “And now we here.”

When the Trojans spilled out of the locker room, onto the field, only stilted silence greeted them. No drum beats or tubas bellowing. (Bands, with all their blowing and spittle, were prohibited.) Without those cues, the assembled families and friends seemed to have forgotten when to cheer, or maybe what to cheer for. Gradually, though, a buzz built in the grandstand, and at last came a full-throated release of seven months of sorrow. “Just getting back,” says Dyer, “that’s a victory in and of itself.”

At around 7:30, Vargas booted the opening kickoff, and just like that football was back in Albany. Not that there was any time to reflect on the moment. Turner County’s return man, Zavaad Bynum, slashed from the right sideline to his left and sprinted 97 yards untouched. The pall returned.

Still, gloom didn’t define the night. Later in the first quarter Kameron handled a shotgun snap, darted toward an opening to his right and dashed through the defense for an 82-yard touchdown. Baseball may yet be his quickest route out of Albany, but in between thunderous hits the 14-year-old steadily ripped off chunks on the ground (adding up to 158 rushing yards, with two TDs) and connected on darts toward the flanks (for 89 more yards and another aerial score).

On the sideline Ju-Marcus squabbled with his defensive teammates about missed assignments, and Moore berated him for peeking inside too often, costing the Trojans on zone-read sweeps. Stanley, the defensive line coach who often gives Ju-Marcus a ride home, pulled the sullen player aside after one of Moore’s tirades, imploring the young man to relish an evening’s escape rather than stress over mistakes. Ju-Marcus nodded, appreciating the reminder that football is a refuge, a rare place where he can cling to his youth.

The Trojans entered the half with a one-point lead, but after the break their stunted preseason—just two weeks in full pads, not enough time to calibrate their bodies—caught up with them. Turner County, already playing its fourth game, appeared markedly sharper and in the third quarter tacked on 21 points. On the other side, several Dougherty players cramped up. One tore his ACL on a kick return. Another broke his wrist on a tackle.

In the stands, as the night wore on, some younger fans pulled their masks down to their chins. Groups began to huddle in tighter packs, portending a national uptick in COVID-19 cases through the fall—one that could imperil the rest of Dougherty’s season. Gilbert quietly pulled players aside, imparting gentle lessons about footwork and poise, but as the points piled up, Moore’s roaring voice became the evening’s soundtrack. (It’s a scene that would repeat itself as the season wore on: Dougherty lost its next three games.)

Around 10 p.m., after the clock expired on Turner’s 34–21 win, as players in sweat-soaked shirts ambled toward awaiting buses, Gilbert and Moore settled 10 feet apart on a steel bench along the Dougherty sideline. All night long each coach had worn enthusiasm like a mask in front of his players, but finally these men dropped their guard, revealing the stress of the past months. They sat in silence, cooled by fall’s first chill, and exhaled under two towers of light in an otherwise empty stadium.

Ju-Marcus trudged by, his own cloth face mask dangling from his fingers, thinking about how he had been pushed around in the fourth quarter and about the mistakes he needed to correct: occupying his blocker, resisting the urge to peek inside and, above all, getting stronger.

He doesn’t yet recognize the immense weight he already carries. It’s the same burden Du Bois saw on the backs of beleaguered sharecroppers. It’s the same history that forced Gilbert and Moore to settle on the bench and breathe deep. It’s the same inheritance that Jeff King shouldered until an invisible enemy throttled him. Ju-Marcus doesn’t know that he is already stronger than any 16-year-old should ever have to be. A Black son of Albany, he understands only that he never feels quite strong enough.