Jason Luckasevic was the first lawyer to sue the NFL over head injuries, leading to a massive class-action settlement he describes as a "debacle." Now he's taking on the NCAA "case by case by case" in courts across the country.

In May 2019, Matthew Onyshko sat in his wheelchair at the head of a courtroom in Washington County, Pa., facing a lawyer for the NCAA. Onyshko had played football for Division II California University of Pennsylvania from 1999 to 2003 and, after graduating, became a firefighter in his hometown of Pittsburgh. One day in November 2007, as his wife, Jessica, described it to the court, “He noticed when he was going to fight a fire that he had trouble getting his gloves on, and his hands weren’t quite as strong as they were before.” A few months later doctors diagnosed the father of two with the degenerative brain disease ALS. After he watched a report on former Saints defensive back Steve Gleason’s experience with ALS on Super Bowl Sunday of 2012, it occurred to Onyshko that the head injuries he suffered playing football likely caused his condition. His doctors, who told him that he had no genetic precondition for the disease, agreed.

Now fully paralyzed and no longer able to talk, the 38-year-old former linebacker communicates through a device that tracks his eye movement to spell words and produce speech. In the courtroom, Onyshko needed help shifting his position so that the sun wouldn’t interfere with his gaze. But he was still able to testify that he suffered “at least 20” concussions at Cal U, though he never reported them to trainers because “I didn’t know they were an issue.” Nobody had educated him on the symptoms, Onyshko said, which is why he filed suit in state court against the NCAA in June 2014. “The NCAA either knew, or should have known, of the risks to student athletes of repeated head trauma,” read the complaint.

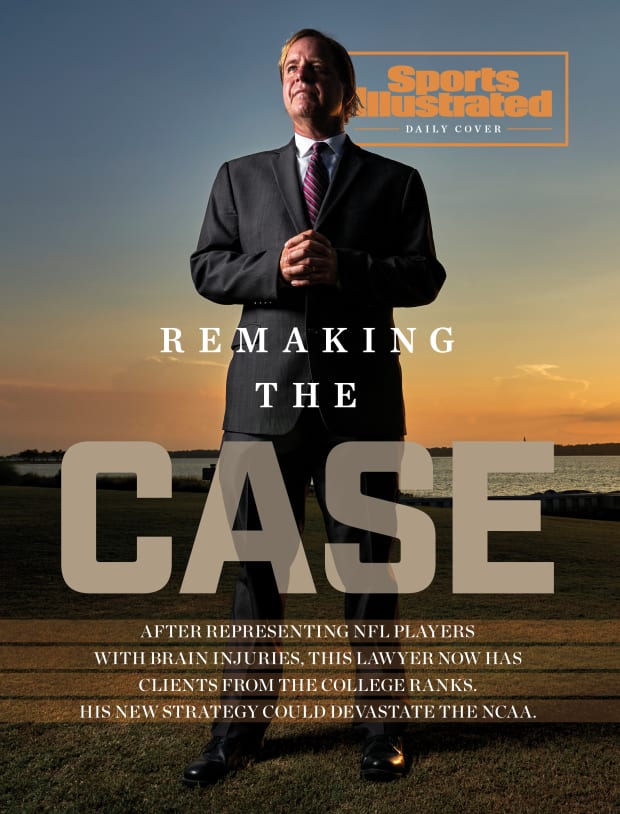

Jason Luckasevic, Onyshko’s lawyer and one of the authors of that complaint, sat nearby. A partner at the Pittsburgh injury law firm Goldberg, Persky & White, Luckasevic was the first lawyer to sue the NFL over concussions; in 2011 he filed for 120 former players in a case that snowballed into a class action involving thousands more. Three years later, as the NFL suit moved toward settlement, The New York Times Magazine wrote a feature on him headlined, "How One Lawyer’s Crusade Could Change Football Forever."

In truth, the NFL has been little more than inconvenienced. Estimates put the league’s payout from the April 2016 settlement at $1 billion over 65 years, more than manageable for a business that generated $16 billion in revenue in 2018 alone. So far, only 5% of the more than 20,000 eligible former players have been paid, due to the Escherian legal and medical gantlet each must navigate to receive money. Luckasevic refers to the settlement as a “quagmire debacle.”

In the NCAA, though, he sees a second chance. Luckasevic believes that, when the NFL suit became a class action, big-time lawyers came in and served themselves more than the former players. Now he’s trying a different strategy, taking on the NCAA in a string of individual brain-injury cases filed in state courts. Onyshko’s was the first of eight suits that Luckasevic and his partners have brought against the NCAA in four states. Five others are being prepared, the lawyer says, with more to come once the court backlog caused by the pandemic eases. “We’re gonna take [the NCAA] on case by case by case,” he says.

The gambit is risky, according to legal experts: The lawsuits will be expensive, time-consuming and as difficult to win as a road game in Tuscaloosa. Luckasevic and his colleagues must persuade jurors that the NCAA should have known playing football could lead to long-term brain disease well before all the research and attention over the last 15 years.

But those legal experts also say this: With the right jury, the cases can be won. And if Luckasevic pulls off even a single victory, the ripple effects could threaten not just the NCAA’s finances, but also its very operational model. Especially at a time when the organization—beset by a revenue-depleting pandemic, congressional scrutiny, and pushes from conferences, schools and athletes for greater power—has never been more vulnerable.

Gabe Feldman, the director of the Tulane Law School sports law program, puts it this way: “These can be incredibly dangerous cases for the NCAA.”

***

The NCAA was founded in 1906 out of a spasm of concern over the brutality of football. After the game’s run-only, flying-wedge style led to the deaths of some 20 players during the 1905 season, President Theodore Roosevelt called the heads of Harvard, Princeton and Yale to the White House and prodded them to lead a reform movement that resulted in the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Today, football revenue flows directly to schools and conferences, but according to the NCAA’s most recent available IRS filing, the Indianapolis-based nonprofit made over $1 billion in revenue in 2018, largely from March Madness.

That same tax form includes a mission statement. “Every year, the NCAA and its members equip more than 480,000 student-athletes with skills to succeed on the playing field, in the classroom and throughout life,” it reads. “They do that by prioritizing academics, well-being and fairness.”

Luckasevic’s contention is that the organization has long been more concerned with revenue than well-being. As far back as the early 1900s, doctors were warning in medical journals about the effects of concussions. In 1928, a New Jersey physician named Harris Martland explicitly linked hits to the head to long-term brain damage, writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association on “punch drunk” boxers. Martland observed that “there is a very definite brain injury due to single or repeated blows on the head or jaw” and that “marked mental deterioration may set in necessitating commitment to an asylum.”

Luckasevic and his team have found repeated reference to concussions and punch-drunk athletes in NCAA records and archives. The official 1933 NCAA medical handbook states, for instance, “There is definitely a condition described as ‘punch drunk’ and often recurrent concussion cases in football and boxing demonstrate this.”

During an interview earlier this year in Luckasevic’s Pittsburgh office, one of the lawyers working with him, Max Petrunya, pulled up a digitized version of the 1948 NCAA boxing guide, which the lawyers’ researchers had found in the NCAA archives in Indianapolis. On page 9, the guide warns against pairing skilled sparring partners with tomato cans. “Such a poor boxer if used in the preparation of the squad for two or three years can very well take sufficient head punishment to produce permanent brain injury in later life,” reads the entry, written by a University of Wisconsin neuropsychiatrist.

Recent years have of course seen medical breakthroughs linking football to brain damage, especially around the effect of subconcussive hits. Punch drunk has also acquired a new name: chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. There is still much that’s unknown about CTE but, according to Kathleen Bachynski, a public health professor at Muehlenberg College who studies football, it has long been “very well accepted that getting hit over and over again is not a good thing for your brain.”

Bachynski cites a 1952 New England Journal of Medicine survey of injuries on the Harvard football team (also noted by Luckasevic in his suits). The chief surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Augustus Thorndike, wrote that athletes with three or more concussions should not play contact sports: “The college health authorities are conscious of the pathology of the ‘punch-drunk’ boxer.”

Until recent years, though, that consciousness rarely reached college football players. And even as the notion of a punch-drunk boxer became engrained in the culture, the broader public never took the leap to imagine punch-drunk football players. “It’s a really fascinating story of both knowing and not knowing,” says Bachynski. “There just was a cultural looking away, or a cultural downplaying.”

In April 2016, as part of Onyshko’s case, Luckasevic deposed Cedric Dempsey, the NCAA’s executive director from 1994 to 2003. Asked whether the topic of concussions or head injuries was ever brought to his attention during that time, Dempsey replied, “I just don’t recall.”

In 2010, when it had become impossible to look away, the NCAA ordered schools to develop plans for managing concussions. There was, however, no enforcement mechanism. On health matters the association nearly always favors guidelines over hard rules, says Dionne Koller, the director of the University of Baltimore’s Center for Sport and the Law—the better, she notes, to avoid liability in case of lawsuits.

***

The walls of Luckasevic’s office are decorated with autographed photos of NFL clients, press clippings and a framed picture of his two daughters, now 11 and 12.

Sitting in a beat-up leather chair behind his desk, the lawyer said that he still takes many nonfootball cases, and that he profited little from the NFL settlement. His firm was awarded $328,575 out of the $112 million in lawyer fees approved by the judge, though Luckasevic also receives 17% of his clients’ payouts.

While he no longer watches football, Luckasevic grew up in a family with Steelers season tickets and knows that the team is religion in his hometown. As the NFL case progressed, he started to receive threats. “It was mainly like, You’re trying to kill football. We hate you. What’s wrong with you? You ought to die yourself,” he says. Worried about how his daughters would be treated in school, Luckasevic moved with his family to South Carolina in 2016 and now commutes to Pittsburgh. Going up against the NFL, he says, has “shaped me and molded me as to who I am and why I do what I do now.”

Luckasevic was drawn into the NFL fight by coincidence: He was friends with Bennet Omalu, the forensic pathologist at the Allegheny County coroner’s office who took on the NFL after finding CTE during the 2002 autopsy of Steelers great Mike Webster. At first Luckasevic was starstruck at meeting the NFL heroes who would become his clients, often calling his dad or brother to gush. But, he says, “I quickly learned that [the players] were coming to you for help.” As his client list grew into the dozens, Luckasevic saw their struggles up close. “You feel bad. You feel sad. You want to fight harder for them,” he says. “You sympathize with them, cry with them.”

When he filed his suit against the NFL in California federal court, he says, “We were a band of 120 brothers.” The band quickly grew, as retired players from all over the country began to sue. In early 2012, a federal judicial panel consolidated all the cases into a class action. Chris Seeger, from the firm Seeger Weiss, was appointed lead counsel. Suddenly, Luckasevic was on the outside looking in.

Most of his clients have been unable to meet the burden required to claim money from the settlement—including the family of Mike Webster. “You gain so much trust and love and respect and friendliness with the players,” Luckasevic says. “And then the carpet’s just pulled right from under you. What do you do? You look like a jackass.”

One day in October 2013, Luckasevic opened his inbox and saw an email from a man named Matthew Onyshko. “I was diagnosed with ALS seven years ago,” it said. “It was college football. I know your firm represented many NFL players, I wanted to see if your firm would participate in a concussion lawsuit against the NCAA.”

***

Usually, when plaintiffs take on a big entity like a tobacco or pharmaceutical company—or the NCAA—they join in a class action. There’s a concussion-related consolidated litigation, similar to a class action, against the NCAA made up of 380 cases slowly progressing in federal court in northern Illinois right now. And a previous, similar class action against the NCAA resulted in a settlement last year providing for medical monitoring of former players, though no cash awards. Class actions allow plaintiffs to pool their resources and offer an orderly process for all sides—including the plaintiffs’ lawyers, who generally get paid only if their clients do.

Luckasevic’s decision to pursue individual cases, which move faster and are less predictable, introduces a chaos factor. The top award to an individual allowed under the NFL settlement is $5 million; in the Onyshko case, Luckasevic and his colleagues asked for $9.6 million. And because Luckasevic filed his cases in state courts, they cannot easily be rolled into a nationwide class action.

When the Onyshko trial began in April 2019, Luckasevic and his partners were riding some momentum: The previous summer the NCAA had agreed to settle a case that Eugene Egdorf, a Houston lawyer whose firm has partnered with Luckasevic on the NCAA lawsuits, spearheaded on behalf of the family of former Texas defensive lineman Greg Ploetz. Egdorf and Luckasevic scored a major victory in the case: NCAA chief medical officer Brian Hainline acknowledged in his deposition that there is a link between brain diseases and football.

In many ways the Ploetz and Onyshko cases were similar; once Luckasevic and Egdorf had the template for a concussion lawsuit, all they had to do to file future ones was swap in the names and details. But there were also important differences. Ploetz died in 2015 at age 66 and was subsequently diagnosed with CTE, which can be confirmed only through autopsy. Because Onyshko was alive, NCAA lawyers could argue that there was no proof his injuries were connected to football. The Washington County judge went so far as to forbid any allusion to CTE.

In his opening remarks, NCAA lawyer Arthur Hankin drove at the cracks present in almost all concussion suits against the NCAA. One challenge is proving that a brain injury is due to college football and not another trauma. What if the plaintiff played Pop Warner? Or once fell off a bike? “Matt Onyshko played football for eight years before he went to Cal U, and I hear high school football in western Pennsylvania . . . is pretty rough,” Hankin told the jury.

Another challenge is proving negligence: While plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the NFL alleged that it actively covered up wider knowledge around brain injuries, the allegation against the NCAA is essentially that officials knew—or should have known—and did nothing. There’s no smoking gun, no account of a steamy backroom filled with fat cats tapping cigar ash onto medical reports—just a long history of “cultural downplaying.”

In the trial, Hankin embraced bare-knuckled arguments that are poor p.r. but legally effective. Despite the high number of football players with ALS, he said no connection can be drawn. “This case is about ALS. That is the only diagnosis Mr. Onyshko has,” Hankin said. He also accused Onyshko of shifting the timeline of his symptoms to make them seem related to his college career.

While questioning Onyshko on the stand, Hankin fixated on the former linebacker’s failure to report his concussions, even though it was common for athletes of his era to play through them. Hankin asked, “Did you ever report an injury in the five years that you were at Cal U?” When Onyshko replied, “One,” Hankin followed, “What was that? ... Was that a thigh bruise in the spring season of 2000?” Onyshko confirmed it was. In his closing, Hankin hammered, “Matt Onyshko was never diagnosed with a concussion. Never, not once.”

Hankin also argued that athletes’ health was not the responsibility of the NCAA but of individual schools. He presented a chart diagramming the NCAA’s structure and asked jurors, “Now, who would be primarily responsible for that student-athlete? The people in Indianapolis or the people in California, Pennsylvania?”

His arguments worked: When the jury returned its verdict in August 2019, it was 10–2 in favor of the NCAA.

***

Luckasevic believes that he lost only because the judge hemmed him in on technicalities. That’s why he has appealed—a process moving forward, as the sides exchange briefs—and is also currently fighting several similar cases, none of which have yet reached verdicts.

There are also some similar state-level cases that Luckasevic is not involved with. It could take just one jury favoring a sympathetic hometown hero like Onyshko over the NCAA’s hard-charging lawyers to produce what Feldman, from Tulane, calls “a snowball effect” that would lead to more plaintiffs and more lawsuits popping up all over the

country. Last year alone 73,712 men played football in the NCAA’s three divisions—the well of potential plaintiffs is almost endless. If enough cases emerge, the cost of litigating them, let alone paying settlements or damages, could be massive for the NCAA. It could also knock the organization back on its heels in negotiating a settlement for the consolidated litigation progressing in Illinois. At a time when the coronavirus has depleted the association’s resources, “That’s a huge deal,” Feldman says. “Every financial risk becomes magnified.”

But the potential damage goes beyond money, says Nellie Drew, the director of the University of Buffalo School of Law’s Center for the Advancement of Sport. “If you had just one verdict, banner headlines saying 'NCAA Held Responsible For Player’s ALS,' I’m not sure you can buy yourself back from that fallout,” she says. Koller says that a win might not even be required: Forcing the NCAA to publicly make its hard-edged legal arguments over and over could be damaging enough. She compared it to the outrage last March after U.S. Soccer’s lawyers argued in filings that women’s national team players were inferior to men. “I think it just continues to erode their image,” Koller says. “And so, for long-term legitimacy, I think that’s where they’re in trouble,”

What does that trouble look like? It could mean having to beg for funds from Congress, in exchange for delivering changes like the currently proposed athletes’ bill of rights. Or being forced to finally bow to outside pressure and enact dramatic reforms. Speaking in the spring, NCAA general counsel Scott Bearby said that he is not concerned by Luckasevic’s lawsuits: “I think we’re going to win the cases. But if the notion out there is that there is a lawsuit around every injury that everybody has or about every bad call, then I do worry about the future of sport.”

Back in Luckasevic’s office, Petrunya said that he believes their suits “will change the world,” comparing the cases to asbestos and tobacco litigation. Luckasevic wouldn’t go that far. He’s well aware of how difficult these cases are to win, especially when they’re being fought in football holy lands like Pennsylvania or Texas. “Oh my goodness gracious,” he said. “You’re not suing tobacco. You’re suing football. Football tastes better.”

How much does America crave the sport? Consider the major conferences’ decisions to play through the coronavirus pandemic. Luckasevic says that choice raises the same core questions as his lawsuits: How much do the schools, conferences and the NCAA care about athletes’ health? How willing are they to risk it?

Legal experts predict a cascade of player lawsuits related to the virus. So far, schools that have resumed play have experienced scores of infections, but no catastrophes. Many players’ size could put them at elevated risk, though—even ones whose seasons have been suspended. On Sept. 9, a 355-pound D-II defensive lineman died from a blood clot in his heart after contracting COVID-19. Like Matthew Onyshko, Jamain Stephens, 20, played for California University of Pennsylvania.