Years after he broke the MLB color barrier, the Brooklyn Dodger's impact reverberated throughout the sporting world, the city he represented and beyond.

From TRUE: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson, by Kostya Kennedy. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Game 6, 1956 World Series, Brooklyn

It was the bottom of the 10th inning, two outs, scoreless, and the Dodgers had Jim Gilliam on second base and Duke Snider on first.

Jackie Robinson was coming up to face the Yankees’ Bob Turley for the fifth time in the game.

He stepped across home plate in front of Yogi Berra, rolled his shoulders and gently wagged his bat before finding his place in the batter’s box. The Yankees outfielders played Robinson deep and swung over toward the left side. Mickey Mantle in center, Hank Bauer in right, Enos Slaughter in left. The shortstop, Gil McDougald, was playing well over into the hole, allowing Gilliam to take a substantial lead at second base, and the second baseman, Billy Martin, kept dodging over to try to lure Gilliam back to the bag.

So very much would happen in Robinson’s life over the weeks and months to come. Japan. The Spingarn banquet. The job at Chock Full. His trade, authorized by Walter O’Malley, to the New York Giants. Retirement from the game. Meetings with the NAACP. Letters to Martin Luther King Jr. But right now, there was only this.

Robinson fouled off the first pitch, and the second came in outside. One and one. Turley caught the ball back from Berra and got up on the mound and then stepped off and drew a long breath and then got back onto the mound again. Gilliam kept his hands on his hips as he edged off second base, and then, as he moved farther away from the bag, he dropped his arms so that his hands hung below his knees. Then he got up on the balls of his feet, ready to run. Turley looked in toward the plate, stepped forward and threw the ball, and Robinson swung.

You could tell it had a chance by the sound of it—clock!—a high line drive out toward the gap in left-center field. Slaughter moved sharply toward the ball and leaped with his glove outstretched. But the ball got over him and landed on the cinder path and took a hop off the ad for Schaefer Beer. Gilliam gathered speed as he rounded third, and when he touched home plate, his fellow Dodgers streamed out of the dugout and some fans spilled out of the seats. The big Brooklyn crowd thundered and roared, and the old stadium shook and shook and shook in the autumn air. The Dodgers had won. There would be a Game 7. When Clem Labine reached Robinson in the thicket of teammates surrounding him on the field, he kissed Robinson’s cheek for all he was worth.

This was in the late afternoon on Oct. 9, 1956: 10 years and 175 days since Robinson had played his first game as a Montreal Royal, nine years and 172 days since he officially broke in at Ebbets Field. It was the 314th day of the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala.—another 74 days would pass before it would end in success. This was the day on which the Dodgers beat the Yankees in a World Series game for the final time, and it was the day that Jackie Robinson stroked that game-winning single, the 1,550th—and final—hit of his Dodgers career.

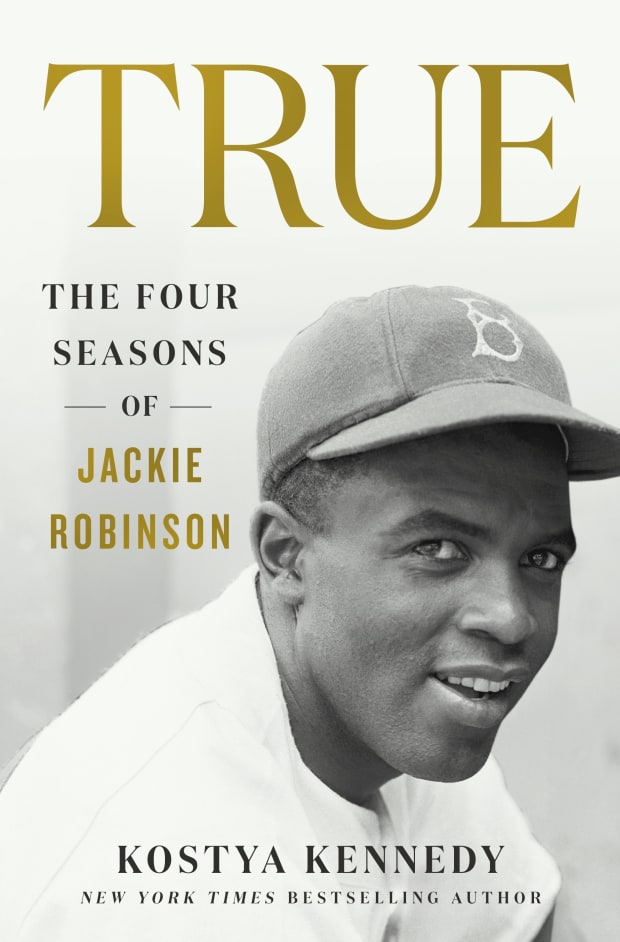

John G. Zimmerman /Sports Illustrated

There was still Game 7 to be played, the next afternoon at Ebbets Field, with Don Newcombe pitching for the Dodgers. Newcombe had won 27 games in 1956 and was voted the National League’s Most Valuable Player. But in Game 7, he did not pitch at that level. He gave up a two-run homer to Berra in the first and third innings, and left the game in the fourth with Brooklyn trailing by five runs. The Yankees would go on to win 9–0.

Robinson was the last World Series batter, swinging and missing at strike three and then, when the ball bounced away from Berra, racing to first base, in full flight, squeezing the last life out of the game and the Series. But Berra got to the ball and threw to first base for the out. The Yankees gathered near the mound in celebration, and Robinson turned off to his right and into foul ground.

He would be back at Ebbets Field after that afternoon, to collect his things and say goodbye to the staff—he always tipped the clubhouse guys well, home and away—but he would not be back on the diamond. And even then, he knew that this might be true.

You could see Jackie Robinson pausing there after the final out on that October afternoon, and looking out over the ballpark, at the fan of the infield and the white bases and the green outfield grass and the bleachers beyond. His office. The ground where he had plied his craft and defined his mission, established himself and asserted himself again and again. You can see him there, still and thoughtful at a standing rest, solemn as a lion in a tender moment, and then turning his body—the big shoulders and powerful arms, the sturdy trunk, legs thick as the thickest mattress springs, the body that had done its part to change the world—away from the field and beginning to move in his aching gait toward the dugout and on through the tunnel to the locker room, where he would talk to the newspapermen and feel the fresh disappointment of the World Series loss and then peel off his flannels, his Dodger blues, his uniform, for the last time in his life.

Explore: Never-Before-Seen Photos of Jackie Robinson from 1956

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Riverside, 1972

The Riverside Church rises off a crest of land on the far West Side of Manhattan, overlooking a spread of forested parkland, a wide commuter road, and beyond that road, the Hudson River. The church occupies a city block just a Furillo’s throw from 125th Street, the Harlem thoroughfare home to the Apollo Theater and, from 1964 to ’90, the Freedom National Bank. Built in the late ’20s, the church projects an air of classic grandeur, modeled as it is on the 13th-century cathedral at Chartres. The nave of Riverside Church spreads nearly 90 feet wide and extends more than 200 feet from entranceway to altar. The ribbed ceiling reaches eight stories high at its vaulted peak, and the arched bays along the sidewalls curve around panes of stained glass. Colorful mosaics depict scenes both Christian and non-Christian, a spirit in confluence with the church’s mission to be “interdenominational, interracial, international.”

Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a congregation here—decades later, so did Nelson Mandela—and during the 1960s, the Riverside Church proved fertile ground for prayer, thought and discussion around civil rights. In ’69, the activist James Forman interrupted a Sunday sermon by climbing the steps of the chancel and reading aloud the Black Manifesto. On important days, the church might fill to its official capacity of close to 2,500 people, although many more than that crowded in, and many, many more pressed along the neighboring streets and sidewalks, on the late morning and early afternoon of Oct. 27, 1972, for the funeral of Jackie Robinson.

Three days had passed since Robinson’s sudden collapse onto the floor of his home on Cascade Road, in the early morning, with his wife of 26 years, Rachel, by his side. She had called the Stamford, Conn., police and gone to the hospital and phoned Sharon, their daughter, in D.C. to tell her he was gone. Rachel helped to organize the days of public viewing and to set up the funeral, and she discussed the handling of the eulogy and specified who would be the pallbearers. When Rachel asked Bill Russell, the great and principled basketball star, to be among them, Russell broke into tears. “What an overwhelming honor,” he said. Russell was in junior high school in West Oakland when Robinson started with the Dodgers.

The others who would carry Robinson’s casket were old teammates and peers: Newcombe, Gilliam, Ralph Branca, Pee Wee Reese, Joe Black and Larry Doby. All through, the church was dotted with great athletes and notables: Joe Louis. Hank Greenberg. Willie Mays. Dick Gregory. Sargent Shriver, right off the campaign trail. A delegation of 40 people sent by the president. Cab Calloway. Betty Shabazz. Ed Sullivan. Bayard Rustin. Beyond the famous people, and the grieving family, and the many who had known Robinson in his professional lives, the strength of the assembly came as well from the many who had never met Robinson, but whose lives he had also changed. A high school teacher from New Jersey. Off-duty policemen. A barber who’d shut down his shop through the middle of the day. Reporters would comment on the interracial makeup of the funeral gathering, calling it a melting pot.

Ira Glasser was 34 years old and the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, and he still had his Brooklyn boyhood running through him. He’d come to the funeral with an NYCLU lawyer, Alan Levine, who had been weaned on the same team and the same man. “I knew that I owed a lot of the way I approached the world—what to do with my sense of right and wrong—to having seen Jackie Robinson play,” Glasser said. Fact is, the Riverside Church that day was lousy with Dodgers fans.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

A series of ministers bade Robinson farewell that afternoon—Wyatt Tee Walker read from Corinthians—and a 60-voice choir delivered “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who had been on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968, gave the formal eulogy. “Today we must balance the tears of sorrow with the tears of joy,” Jackson began. “Mix the bitter with the sweet. Death and life.”

The pews were packed. People stood in the outer aisles, in the hallways and in the open bays. The silence of the transfixed filled the great church as Jackson paused between his opening phrases. “When Jackie took the field, something reminded us of our birthright to be free,” Jackson said. And he added: “He didn’t integrate baseball for himself. He infiltrated baseball for all of us, seeking and looking for more oxygen for Black survival, and looking for new possibility.” By the end of the eulogy, a half-hour long, the silence had yielded to responses from the crowd, cries of Hallelujah! Amen! and You’re right! that echoed off the great stone walls. “Jackie’s body,” said Jackson, “was a temple of God, an instrument of peace.”

Afterward, on the streets outside, crowds gathered around the ballplayers: Ernie Banks, Willie Stargell, Elston Howard, Monte Irvin, Vida Blue, Campy, Oisk. Also Henry Aaron, who was then 41 home runs shy of Babe Ruth. “Most of the Black players from Jackie’s day were at the funeral,” Aaron would say. “But I was appalled by how few of the younger players showed up to pay him tribute.”

Buy TRUE: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson

For all the love and reverence at the funeral, you couldn’t anticipate what the reception would be once the hearse and the trailing cars pulled away from the Riverside Church and began traveling through Harlem, and then through Bedford-Stuyvesant and to the cemetery in Brooklyn. Robinson had never found firm footing with the newer wave of the movement. He’d clashed with Malcolm X and differed sharply with Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a beloved son in Harlem. Robinson once chastised Black protesters outside the Apollo Theater. More to the point, in recent years, Robinson’s voice had not resonated so widely as it once had. “We knew Jackie Robinson wrote columns for the Black newspapers,” says the scholar and historian Gerald Early, who was 20 years old in 1972. “But we didn’t necessarily read them. He was my father’s hero.” So, when the funeral procession began to move through the streets, there was no telling just how the neighborhoods would respond.

People came out of their apartments. They came out of their shops and they came off the schoolyards. Cabdrivers stopped their rides in the middle of the fare. People stood in doorways and sat on rooftops and leaned out of windows. They gathered thick along the sidewalks and they jostled out onto the streets. Men and women. Old people and young. They wore dress suits and grocery store aprons and uniforms from their schools. Some along the route raised their fists in the Black Power salute as the cars rolled by. Others bowed their heads. Some called out Jackie’s name, some stood silently and some put hands above their eyes like a visor, allowing tears to roll down their cheeks rather than interrupt the moment to wipe them away. The police estimated 30,000 people along 125th Street, 5,000 at the mouth of the Triboro Bridge, 2,000 waiting at the graveyard. There was a time in many of these people’s lives when Jackie Robinson carried the brightest light of hope.

From the pulpit, Jackson had described Robinson as “a rock in the water, hitting concentric circles and ripples of new possibility.” An incoming rock disturbs the surface as well as the water below, and it rouses, too, the sediment on the water’s floor. The smallest and most measurable indicators—the height and length of a rippling wave, say—can only suggest the larger impact.

Before 1949, the year Jackie Robinson hit .342 to lead all batters, no Black player—because of the history of exclusion—had finished among the top seven hitters in the National League. In 1972, the NL’s top seven hitters were Billy Williams, Ralph Garr, Dusty Baker, César Cedeño, Bob Watson, Al Oliver and Lou Brock.

The condolence letters that arrived at Cascade Road were another measure, another small start. Wrote Ralph Abernathy: “Our nation in general and Black people in particular have lost a pioneer, a champion. . . . Jackie Robinson belonged not only to the Brooklyn Dodgers but to all Black and underprivileged people in America.”

Ira Glasser began his letter, “Dear Mrs. Robinson: . . . I thought that perhaps you would like to know—insofar as I can explain—what it meant in the late forties and early fifties for a white boy to have a Black man as his hero.”

Aaron sent a telegram. This was one year, five months and 11 days before he hit Al Downing’s fastball over the left-field wall in Atlanta. Aaron had gotten his start

playing Negro leagues ball with the Indianapolis Clowns.“I share with you your grief upon the passing of a great American. Baseball and the Black athlete are the poorer because of his death. My own success in baseball has been in large measure because Jackie Robinson marked the trail well. May you and your family take consolation in knowing that he did so much for so many. —Henry Aaron.”

At Cypress Hills Cemetery, six miles from the site of the first base bag at Ebbets Field, the teammates carried the casket from the hearse to the gravesite, and Robinson was lowered into the earth beside his son, Jackie Robinson Jr., who had died in a single-car crash in 1971 at the age of 24.

Two burials in 16 months. Jackie and Rachel’s son, David, stood beside the grave, and so did Robinson’s siblings—Edgar, Mack and Willa Mae all in from Pasadena. Neither Sharon nor Rachel got out of the car. This scene, Rachel knew, was more than she needed. She had held Jack as he lay in the hallway outside their room, and she had greeted mourners at the funeral home and she had taken in the eulogy through her sense of disbelief.

She wanted to keep certain memories clear: Jack in his vibrancy, insistent, wry, purposeful. My dearest Jack, my giant, Rachel had thought on the morning he fell. Clouds had now moved in over Brooklyn—“dark clouds” in the reporter’s words—and the larger group at the cemetery began to disperse and get into their cars. The loss, Rachel would say, felt unbearable, although she knew that she would bear it. She would allow herself to disappear for a time into grief and then she would emerge. Lifted by her own implacable strength, buttressed as well by Jack’s, she would begin to reassemble herself and go on.

More MLB Coverage:

• The True Legacy of Jackie Robinson’s Dodgers Debut Is Complicated

• Never-Before-Seen Photos of Jackie Robinson from 1956

• Pulling Clayton Kershaw From the Perfect Game Made Too Much Sense

• Braves Sacrificed a World Series Repeat to Dominate the Decade