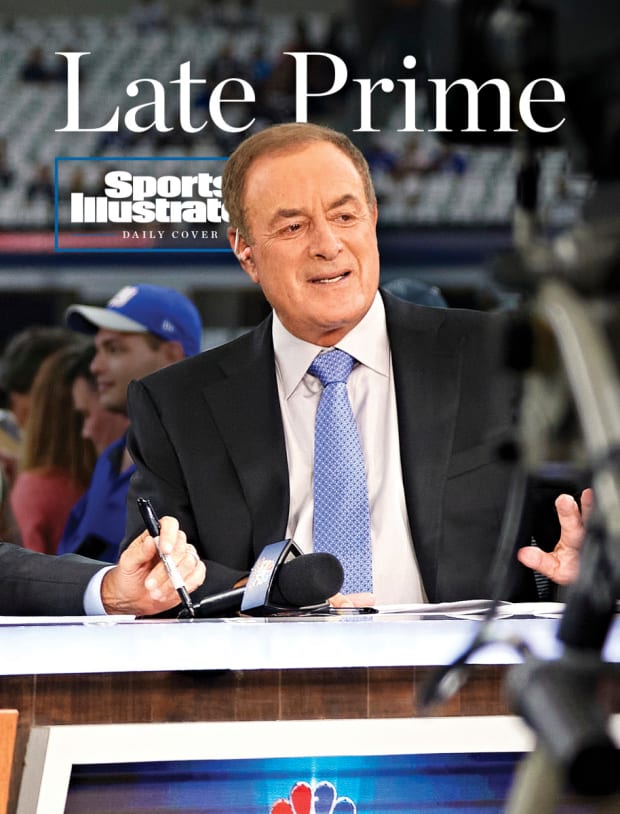

The legendary NFL broadcaster goes deep on his career. But is he headed to Amazon Prime? He prefers not to use periods.

As lopsided NFL trades go, well, forget about Matthew Stafford for Jared Goff. In 2006—in what was largely a face-saving PR stunt—ABC allowed its lead pro football play-by-play voice, Al Michaels, to decamp to NBC in exchange for the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a precursor to Mickey Mouse created by Walt Disney in the 1920s. Since the swap, Oswald has sat on the intellectual property equivalent of the injured list.

Michaels, on the other hand, became the centerpiece for Sunday Night Football, a ratings juggernaut for NBC that, most weeks, outdraws every other show on TV. As with any sports franchise, success has plenty of parents. The show’s director (Drew Esocoff) and executive producer (Fred Gaudelli) take back seats to no one. Same for sideline reporter Michele Tafoya, who just finished her final season. The original SNF analyst, the late John Madden, may be the GOAT, but when he was replaced in 2009 by former All-Pro receiver Cris Collinsworth, ratings remained astronomical.

And yet the quarterback has been, undeniably, Michaels. He’s 77 now, but he is undiminished since he began working for ABC in the late 1970s. He marries a crisp professionalism with a teenager’s subversiveness—the Rascal, he calls his alter ego, the prank-calling sports fan. More than 40 years after Michaels famously asked about our faith in miracles at the '80 Olympics, his voice has lost none of its authority. And his sixth sense for knowing when to speak and when not to remains wondrous.

A brief programming break for some full disclosure: Several years ago I worked with Michaels on his memoir, You Can’t Make This Up, though worked is a bit of an exaggeration. Basically, we ate a lot of meals—his never including vegetables, save ketchup—while he played the (many) hits from his 50 years in the business. Some memoirs reveal hidden sides and unexpected dimensions of the subject. In this case, not so much. Al Michaels is pretty much the fun, mischievous uncle you think he is as he broadcasts into your living room.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Michaels just finished the final year of his NBC contract. It’s more than likely he will leave the network to lead Amazon’s NFL coverage. (No cartoon rabbit required from Amazon; Mike Tirico’s waiting in the wings.) A career that began when long-distance calls came with a toll very well may continue on a streaming platform.

Uncharacteristically, Michaels has been coy about his future. “I’m focusing on the present,” is his fallback. When flashed a look that says, You’ve gotta do better than that, he smiles. “I was talking to Vinny [Scully], and when people asked him about his future, he used to deflect by saying, ‘If you tell God what your plans are, He just laughs at you.’ I’m not quite that spiritual, so I’m not sure I can pull that off.”

On Feb. 13, Michaels will sit next to Collinsworth and call his 11th Super Bowl. That it will be played in Los Angeles, his home since the 1980s—well, if in fact that is his final SNF broadcast, there will be worse ways to go out.

In the midst of the NFL postseason, over a long breakfast at a Brentwood diner—no veggies—we reprised our drill from a few years ago. Michaels spun yarns; I listened, laughed and sometimes remembered to take a few notes. Some outtakes, lightly edited for brevity and clarity:

Sports Illustrated: How do you explain the NFL’s hold on the culture?

Al Michaels: I don't want this to sound self-serving, but television is huge. Huge. Even I’m amazed—having been in the business my entire professional life—at how beautiful it looks. I mean, it’s a spectacle. And with the technology—the cameras that are everywhere, the cameras that fly over, the angles they give you, the closeups—you never saw this years ago. It’s spectacular. And it’s drama. It is unscripted drama.

And a lot of the rest of television is . . . there’s some great stuff out there, but not a lot. Once in a while, you’re going to see a Netflix thing that’s really great. Or Amazon Prime. But football, especially the NFL, which is the highest level, you can’t match this drama.

That Raiders-Chargers game? [In Week 18, Las Vegas won, bizarrely, on a last-second field goal, to make the playoffs, in what might have been Michaels’s final regular-season SNF game.] That will be the best show in Vegas this year!

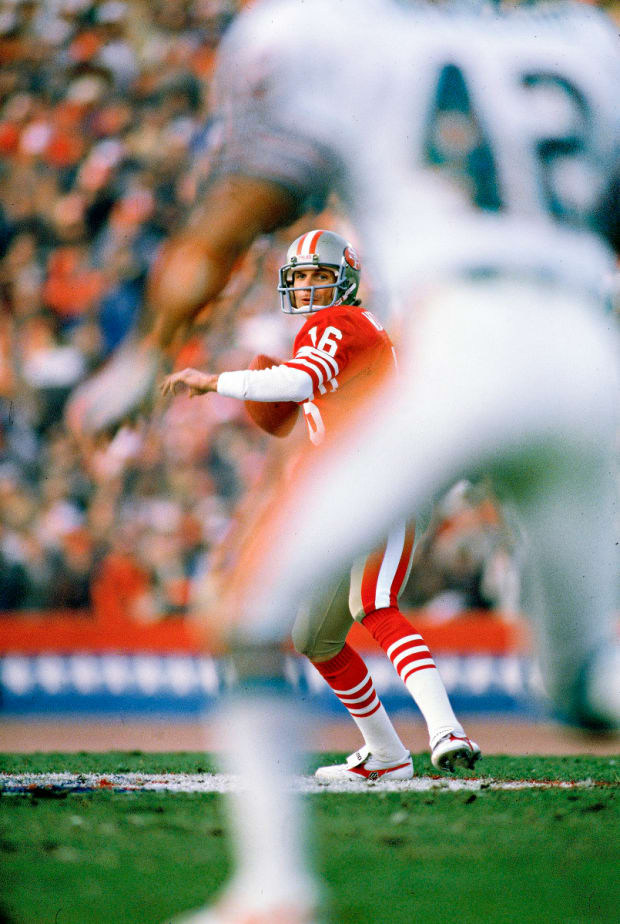

SI: Your first Super Bowl was ...

AM: 1984. Montana beat Marino. I’m on the studio set and it’s me, O.J. and Tom Landry.

Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated

SI: YouTube gold. What about the first Super Bowl you called?

AM: My first one is in San Diego after the 1987 season, the strike year. It's the replacement player year. Washington against Denver. Denver leads 10 to nothing at the end of the first quarter. … And at halftime, it's 35 to 0. Doug Williams threw four touchdown passes and Timmy Smith ran wild. And the final score was 42 to 10.

So I remember I did that with [Dan] Dierdorf and [Frank] Gifford. And we were very excited after the first quarter because until then, most Super Bowls had been very boring. And we were going, “Hey, maybe this could be pretty good!” And next thing you know, “What the hell happened?”

SI: That was your first one, but ...

AM: I've done 10, and six of them have gone down to either the final play or the final few seconds.

SI: So now you get a Super Bowl 10 miles away from your home.

AM: More like 8.6, but who's counting?

SI: It’s Game Day. You’ll be feeling fill-in-the-blank …

AM: Yeah, how do I put it? Intoxicating? I mean that's one way to put it. But it's great. There’s a lot of preparation time. And then those three hours on the air are the reward.

SI: You call a game differently knowing you’ll have three times the audience?

AM: You there are a ton of people out there, but you're talking to one person, really, you know? You haven't gathered 100 million people. One of the things I think about before you do a Super Bowl is tell myself, “O.K. 100 million people watching. We live in a country of 330 million.”

SI: The old question: Help us understand why some players become media stars.

AM: How do you mean?

SI: It’s like predicting which good college quarterbacks become good NFL quarterbacks. Some make the jump, but not always the ones you expect. Why does Pat McAfee make it while some other more [notable] players struggle?

AM: He’s tremendous. I’ll start with the fact, he’s very smart. You can tell from his questions, his takes on things are right on point. And he gets the most out of his guests. He’s not sitting there getting guys to make news by setting them up. There’s a comfort level there, too. Everything is on Zoom. I mean, he’s standing up, just the whole setup there, he’s got the tank top on. He’s got to be fun to talk to.

SI: What about as game analysts? Your last two, John Madden and Cris Collinsworth, are obviously at a certain level. What do they do well and why did others struggle?

AM: Well, the common denominator is the ability to communicate. To be able to put thoughts into words. Not to be cliché-strewn. [MLB analyst and former catcher] Tim McCarver was the first guy I worked with regularly, and we talked about it a lot: Guys come off the field or off the sidelines as coaches. They’re in the ex-jock business. You can’t think of yourself that way. You have to think of yourself as now being in the broadcasting business. There are plenty of guys who know plenty of football. The really good guys understand the flow of television.

“It’s a three-technique tackle!” That’s gobbledygook, right? You don’t just slap on a headset and talk football. There’s a rhythm. You gotta understand what the melody is. The melody is the game. The game has a certain tenor and tempo. And the guys that I work with, they've understood that.

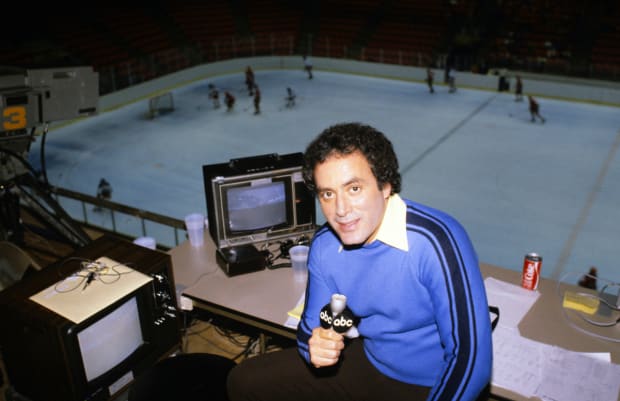

Steve Fenn/ABC Photo Archives/Getty Images

SI: You have a favorite John Madden story?

AM: One of the great Madden stories is that he’s doing a game in Tampa for CBS, and he hates to fly, obviously. So now he’s going to fly home after the game on Monday. His flight is from Tampa to San Francisco with the change of planes in Houston. So they take off and in the middle of the flight, John says, “That’s it, that’s it.” And he vowed to himself, If the plane lands safely, that’s it. He’s off the plane in Houston, will figure out some way to get back to San Francisco. . . . And somewhere out there is the back end of that ticket, which should actually be in the Smithsonian.

SI: What year was that?

AM: 1979. And the [next] time he got near a physical airplane was when he got into the Hall of Fame in 2006. He chartered a good-size plane to take all of his friends and family to Canton from the Bay Area. So when they arrived, John walked down to greet everybody . . . very tentatively. Plane is on the tarmac. It’s not going anywhere. It’s landed. And still, there’s a lot of hesitation.

SI: What made him such a good partner?

AM: He was very curious. And he was hugely smart, very in touch with everything that was going on in the world. And the great thing about John—and look at my last two partners, I mean so many wonderful qualities—but one thing they clearly shared is that I could go anywhere with them and know they’re ready. You know the worst thing in the world is you hang your partner out to dry. You can’t do that. These two guys, that’s why it’s been so great.

NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal/Getty Images

SI: Where is your phone during the game?

AM: It's on the desk, but I don't really look at it too much.

SI: Checking Twitter as soon as they go to commercial, that’s not you ...

AM: Hell no. There are enough distractions. You don’t need that. . . . The vast majority, they play the gotcha game. [During the wild-card round] it took Pittsburgh until the third quarter, I think, to get into Kansas City territory. And I said, “It’s the first time they’ve crossed the DMV.” I kind of knew when I said it. So a few seconds later, I say, “Cris, I just want to make sure you’re paying attention. It’s the DMZ, of course.” And I said, “I don’t want Twitter to blow up, right?” I mean, we live in this world where obviously we’re all connected electronically. Everything is parsed and analyzed.

SI: I remember you saying Curt Gowdy once told you, “Never get jaded.” Somehow, thousands of games later, you haven’t.

AM: I think it comes back to loving sports. I’m a 6-year-old kid and my father takes me to Ebbets Field. Oh, my God, I want to be here every night. And then I wind up with a job where I’m there every night. I want to be where the action is. And I’m getting in for free? I mean that was the impetus as a child.

SI: But you have no less passion and interest for prepping this week’s NFL game than you did for the Hawai‘i Islanders back in the 1960s.

AM: Right, I would say this: It’s studying for a final exam every week. I’m used to it. You have to do the grunt work. People say, “Are you nervous when you go in there?” You go, “No, I’m anxious. I want it to start. Nervous would be if I wasn’t prepared”—and I can’t let myself ever get to that point.

As a consequence, instead of being able to do a lot of reading about different subjects I’m very interested in during the season, I can’t. It’s just like every time I’m ready to go to bed the iPad’s there. What’s the latest story about the Bucs this week?

SI: Do you feel like you’ve diminished in any way?

AM: No, I don’t. I mean, can I pitch a perfect game? It’s almost impossible. There’s a mistake here or there. . . . I rarely watch my game back on at this point in my life because I sort of get pissed at myself. I could have said that better. I could have set this up better. I could have, you know, something that could have been more lively at a certain point. You gotta trust yourself. Ad-lib. Look, could I have ended certain games or things better? But I mean, what are you supposed to do?

SI: You’re not scripting one-liners in advance ...

AM: Oh, God, no no no no no no no no no no no no no. You gotta be in the moment. I don’t want to really say I know what I’m going to say. I never tried to think in terms of putting a period on something because you don’t know how these games are going to end. Otherwise, you’re back to scripted television.

SI: You told Tom Brady, “If you’re still performing at this level, who cares what the actuarial tables look like.”

AM: I can play enough golf, even when I’m working. I’ll never forget the words of Marv Levy. Marv started talking about retiring and said, “If you started thinking about retiring, you’ve already retired.”

SI: We’ll see you somewhere next season?

AM: [Poker face]

SI: Don’t use periods.

AM: Exactly.

• It Hasn’t Been Easy for Joe Burrow; Just Ask His Parents

• Cooper Kupp’s Approach to Greatness

• Arts and Crafts, Belichick-Style: On “Padding,” the Job From Hell