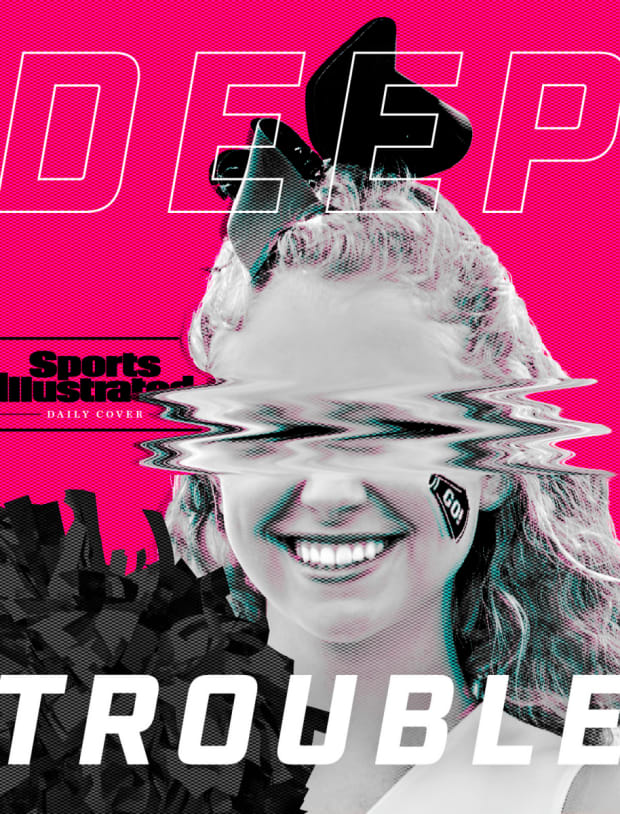

An unsettling cheerleading scandal is going to court, and it raises questions about the threat of video-manipulation technology in sports—and beyond.

If you were looking for a singularly unlikely setting for a blazing sports scandal, you might nominate Victory Vipers Training Center in Doylestown, Pa. Hard by a regional airport, 45 minutes or so north of Philadelphia, the gym sits behind an auto body shop in an office park. It’s the kind of place that a lifelong resident of bucolic Bucks County drives by without much consideration.

Inside, aspiring and accomplished cheerleaders—ranging widely in age, and overwhelmingly but not entirely female—catapult into the air. They work out individually and go through routines as a squad. The instructions and exhortations of coaches echo off of walls lined with various trophies and awards. Outside, an unending flow of weathered minivans and high-end SUVs drop kids off and pick them back up.

It all makes for a tableau steeped in Americana. But last summer, this suburban calm was broken—and broken in the most dramatic, bizarre and postmodern kind of way.

In June 2020, a teenager whom we (and local police records) will refer to as M.H., one of the gym’s top athletes, turned on her phone to find a series of startling communiques. M.H. didn’t recognize the incoming number, but the content suggested that this caller had more than just a passing familiarity with her. A voicemail instructed, “You should kill yourself.” And a series of videos, shared via text message, captured M.H. in unflattering and potentially compromising situations: vaping, drinking alcohol and undressed.

When M.H. tried to call back and establish the identity of the sender, she was informed that the number was not in service. When she responded via text, she got an automated response from Pinger, a free app through which users can communicate anonymously. In addition to being offended and scared as the barrage of correspondences continued, M.H. was confused. She says she’d never before vaped, consumed alcohol or posed nude. Yet, undeniably, there she was in the videos (some of which she recognized had come from her own social media posts). As she would later explain to authorities: That’s me. But that’s not me.

Worse, she would learn: The anonymous tormentor had also sent these videos to the coach at the Victory Vipers gym, home to the ultra-competitive and highly decorated cheer squad. Like many programs, the Vipers require that members abide by a code of conduct, and any of the depicted acts could have constituted grounds for dismissal.

Though fearful that she wouldn’t be believed—Who, after all, can argue with the unimpeachable evidence that is video?—M.H. told her mother about the toxic texts and voicemails. And on July 8, 2020, M.H.’s mother contacted an officer from the Hilltown Township Police Department. Feeling that her daughter’s privacy had been invaded, she went to the authorities much as she would in the case of a home invasion. But she also called the police as a gesture, letting her daughter know that she believed her—that she, too, was convinced this was the handiwork of a crafty, frightening cyberbully.

Throughout the summer and fall, multiple detectives investigated this strange set of circumstances, trying to match the incoming phone number, the IP address and a bandwidth.com address in order to identify the sender. Meanwhile, authorities discovered that other families in the area had been sent similar messages from similar accounts. On August 11, the mother of one local teenager, “N.N.,” received videos depicting her daughter in a bikini. Pasted over one image were the words “Toxic traits, revenge, dating boys, and smoking.” Another teen received a message alleging that she was “drinking at the shore, smokes pot, and uses ‘attentionwhOre69’ as a screen name.”

Quickly, a point of nexus was recognized among the girls: They were all Victory Vipers cheerleaders.

Detectives tried to untangle digital evidence throughout the fall, and on Dec. 18 they executed a search warrant on a Bucks County address, 15 minutes from the Victory Vipers gym, that they’d connected with electronic evidence. There they entered the modest attached home of 49-year-old Raffaela Marie Innella Spone and collected mobile phones, laptops, an Xbox and smart televisions—but not before Spone argued at the door with a detective, who allegedly asked Spone how it was going to feel when she was “in every newspaper and known as the soccer mom who harrasses juveniles.” (The detective also, allegedly, told Spone to “get right with God.”)

Finally, in the first week of March, Spone, whose daughter also competed for the Victory Vipers, was formally charged with harassment and cyber harassment of a child, both third-degree misdemeanors. The allegation was, at once, shocking and somehow unsurprising: Without her own daughter’s knowledge, police say, Spone used deepfake technology to manipulate the media of cheerleaders that she perceived as rivals. “The [goal],” said Matt Weintraub, Bucks County’s district attorney, “was to shame them and get them knocked off the team.”

To pull this off, prosecutors allege, Spone relied on deepfake technology, which uses artificial intelligence to replace the likeness of one person with another in videos and in other digital media. In this case, Spone is believed to have altered the appearance of existing images and videos, yielding a product that reflected the likenesses of the victims.

While deepfakes are often used for fun and for pranks, they can also be employed for the most nefarious purposes, generating what is truly “fake news.” They constitute, essentially, a high-tech assault on the very essence of truth—they can and likely will be used to sow chaos in all sorts of contexts, not the least of which is sports.

“We take it as gospel that a picture is a picture, a video is a video—that they’re unaltered, untainted,” Weintraub maintained at a press conference, straining to conceal his disbelief at the allegations set forth in the case. “This,” he said, “is a setback.”

For such a classic American archetype, cheerleading still resides uneasily within the culture. Is it sport or pageantry? Is it empowering or demeaning?

This much is beyond dispute: Cheerleading requires true athleticism and great reserves of strength, agility, coordination and fearlessness. When director Greg Whiteley completed his irresistible multi-part Netflix documentary Cheer, he noted that the featured cheerleaders were the “toughest athletes I’ve ever filmed.” (For context, his previous series was Last Chance U, featuring a football team.)

Cheerleading, however, also often doubles as a pretext for popularity and prettiness. Surging sport though it may be, judging remains largely subjective. Even the Victory Vipers’ website takes pains to stress that “the selection of our teams is a very tedious and often complicated process.” As long as that’s the case, the landscape will bubble with individual agendas, personality clashes, rivalries and feuds. And that competitive dynamic remains ripe for sabotage.

It was 30 years ago that Wanda Holloway (inevitably shorthanded to “the Texas cheerleader mom” and “the Pompom Mom”) gave this cauldron of competition its fullest and most dramatic expression. The ambitious mother of a 13-year-old from a Houston suburb, Holloway was distraught when her daughter, Shanna, didn’t make the junior high cheerleading team. And doubly displeased when another 13-year-old, whom Holloway positioned as her daughter’s nemesis, filled her own bedroom with cheerleading trophies.

So Holloway hatched a plot that she kept from Shanna. She recruited her former brother-in-law to hire a hitman to murder the rival’s mother, rationalizing that in the aftermath the traumatized teen would be too devastated to focus on cheerleading. Shanna could take advantage of this roster opening and make the squad.

The plan, though, collapsed like an unstable pyramid when the ex-brother-in-law informed the local police of the scheme and wore a wire to record conversations with Wanda. In the end, Holloway was arrested, convicted of soliciting capital murder and sentenced to 14 years in prison, by which point multiple film scripts were being rushed into production. (The conviction, ultimately, was overturned, and before Holloway’s second trial started she pleaded no contest. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison and received probation after serving six months.)

In Bucks County, prosecutors allege that Spone tried to pull off the modern-day equivalent—minus soliciting a homicide—with a few clicks and keystrokes. As the criminal complaint put it: She set out to harass, annoy or alarm “three different juvenile females” and their families and share “seriously disparaging statement(s) or opinion(s) about the child’s physical characteristics, sexuality, sexual activity or mental or physical health or condition.”

The accusations merge the darker side of the human condition with next-gen methods of delivery. Deepfake tech “is now available to anyone with a smartphone,” said Weintraub, the prosecutor. “People feel very safe in their space, and now people’s space includes cyberspace. As this example very starkly points out, we’re not safe in cyberspace. Anyone can grab any image we put out there and manipulate it to look unseemly.”

Broadly speaking, deepfakes have been likened to the next iteration of photoshop, but Siwei Lyu, a professor of computer science and engineering at SUNY Buffalo who specializes in detecting synthetic media, cites a critical distinction. “Photoshop is like a screwdriver,” he says. “You have a screw. You have the screwdriver. But you have to be there and use your hands to push the screw into the wall. Deepfakes are more like a robot. You just tell the robot to put the screw into the wall and it will do it for you. That’s the difference.”

While the technology behind a deepfake is impossibly complex, creating a deepfake is not. “I wouldn't say that everybody can do it now—but it’s pretty close,” says Lyu. “Search online … and you find quite a few deepfake-generating softwares. Some of them are quite user-friendly. … Basically a few mouse clicks; you can select videos and start constructing. It's getting easier and easier.” And if the DIY model fails, Lyu adds, there are users on the dark web who will create deep fakes for a fee.

Lyu, for what it’s worth, has seen the cheerleader deepfakes and is a harsh judge of their quality. “No offense,” he says, “but it’s an amateur job.” In contrast, other attempts can be staggering in their verisimilitude. Perhaps the most well-known deepfake is a depiction of an antic Tom Cruise performing magic tricks (and playing sports, and enjoying a Blow Pop). … Except that Tom Cruise doesn’t do magic. Elsewhere, through deepfake technology: ESPN’s Kenny Mayne appeared in a 2020 State Farm commercial "predicting” the Last Dance documentary on SportsCenter in the late ’90s. Donald Trump counseled Jesse Pinkman on a reimagined Breaking Bad. And an ersatz Mark Zuckerberg explained how “the more you express yourself, the more [Facebook] owns you.”

More seriously, deepfakes have been utilized to manufacture fake news. It doesn’t take much to alter an image and manipulate the words of a politician you don’t like, or a celebrity you seek to embarrass. From cellphone documentation of George Floyd’s murder to surveillance footage of any variety of lesser crimes, we place fidelity in video. But “when you start doubting what you’re seeing, it’s potentially really scary,” says Scott Rosner, academic director of the sports management program and professor of professional practice at Columbia University. “When that video can be doctored, where does that leave us? And where does that leave truth?”

Deepfakes can have significant implications for sports—implications that go way beyond a clever State Farm commercial. The recent Varsity Blues scandal, for instance, was predicated on students of questionable academic qualifications backdooring their way into prominent colleges through sports. The scandal’s central figure, Rick Singer, often relied on counterfeit images to establish athletic bona fides. Most notably, a bogus water polo player posed for an action shot—later photoshopped—while standing on the boom of a backyard pool. One can guess, then, how much more convincing Singer and his clients could have been had they gone the deepfake route.

“Especially coming out of a pandemic,” says Rosner. “You can imagine the role video plays in recruiting—and in negative recruiting. There’s chaos if that video isn’t real.”

It’s easy to posit innumerable other ways that deepfakes could be abused. For decades, coaches have motivated players with so-called “bulletin-board material,” or trash talk from opponents; now, with a deepfake, the offending party doesn’t actually have to say anything offensive. Or: What if a coach or parent challenges a piece of officiating but submits doctored video? What if a fan uses a deepfake to depict a player from a rival team committing an antisocial act?

Just as the Hilltown detective is said to have predicted when he served Raffaela Spone with a warrant, DEEPFAKE MOM HARRASSES JUVENILES did indeed become something of a sensationalized cause celebre, a medley of so many hot-button topics: sex, kids, sports, spite, deception, technology. ... After Weintraub announced the charges, the media—from Good Morning America to the BBC and The Guardian—picked up the story. In Bucks County, it was an engine for conversation and gossip.

And then it wasn’t.

Within a few weeks of the news break, the various cast members in the saga closed ranks. None of the families of the alleged victims in the police report returned inquiries seeking comment. Same for anyone with the Victory Vipers. Hilltown Township police chief Chris Engelhart went dark. Weintraub, the prosecutor, declined comment.

There is, however, one person talking in the days before Spone appears before a Bucks County judge for a preliminary hearing: her attorney, Robert J. Birch. And Birch’s remarks during a lengthy phone interview may offer some insight into why everybody else in the case has gone silent. He and his client assert that the deepfake allegations are, well, counterfeit and manipulated. “Their story,” he says, “is a bunch of bulls---, in plain English.”

Birch is wary of revealing too much of his defense strategy, but, in broad strokes, he and his client claim: The deepfakes weren’t deepfakes at all, and “experts” will confirm this; this low-level misdemeanor has been sensationalized to the point that Spone, who has been subjected to harassment, now has PTSD; and police, ill-equipped to deal with sophisticated technology, botched the investigation.

On April 14, Birch filed a motion to have Spone’s cell phone—the device allegedly used to create the deepfakes—returned to the defendant for forensic examination. And he claims the prosecutor has not complied. “[District attorney Weintraub] is telling media outlets that he has no problem with my client looking at the evidence,” Birch maintains. “Well, they’ve had it since December, and we haven’t gotten a thing yet. What is it that they don’t want me to see?”

Birch declined to make Spone available for comment—he’s worried the prosecution could use her words against her in court—but he says that his client’s life has been “irrevocably damaged” by the charges. “They made her into this criminal mastermind. Here’s a woman who was trying to re-enter the workforce after addressing the estate of her recently deceased mother, and she will never work again. Who is going to employ someone who’s been accused of sexually harassing children?” he asks. “She’s been disgraced.”

He predicts that the case will get held over for trial because of the lighter burden of proof involved in preliminary hearings. Then he will ramp up efforts to “not only prove her innocence, but figure out who did it, because her daughter has been victimized, too.” Inevitably, a civil suit will follow.

On account of both COVID-19 and, one suspects, Spone’s aggressive defense, a preliminary hearing date has been postponed multiple times. It’s now scheduled for May 14. Both the defense and the prosecution envision media coverage wildly out of proportion for a third-degree misdemeanor case.

Meanwhile, a few miles away, after a break to attend competitions, the Victory Vipers gym will reopen in mid-May, staging tryouts for another season. Sources tell Sports Illustrated that all of the teeangers affected by the deepfake scandal have moved on. None remain affiliated with the gym.

But another phalanx of cheerleaders will arrive. They will be expected to abide by a strict code of conduct that now includes a social media policy. (“Profanity, derogatory comments, opinions or personal attacks on members or non-members WILL NOT BE TOLERATED ... by any all-star member or family member.”) And they will fly through the air, contorting themselves in ways that seem to violate the rules of physics, geometry and gravity.

You’ll wonder how it is that humans are capable of such feats. If you didn’t know better, you might not even believe your eyes.

• Ryan Lochte's Last Try

• Pleasant Colony and the Crown of Thorns

• This Basketball Season Is Missing One Thing: Prince