He holds a record that has stood for 33 years. His quarterback is still laughing about it—for more than one reason.

Jim Everett remembers feeling a wave of pride and joy. Surrounded by teammates in the Superdome’s visiting locker room, Everett’s Rams team had just stolen an overtime win. And, in a tradition seemingly as old as the sport itself, coach John Robinson had awarded the game ball to his signal-caller, citing Everett’s grit during a key victory over their NFC West rivals.

Almost 33 years later, that ball still sits on Everett’s mantle. But when he looks at it, it’s not necessarily pride he feels. There is joy, but a different kind. “I laugh about it daily,” Everett says from his Laguna Niguel, Calif., home—cracking up frequently while discussing the topic. “It’s years later and I still laugh, ‘They gave me the game ball?!’”

Otto Greule Jr/Getty Images

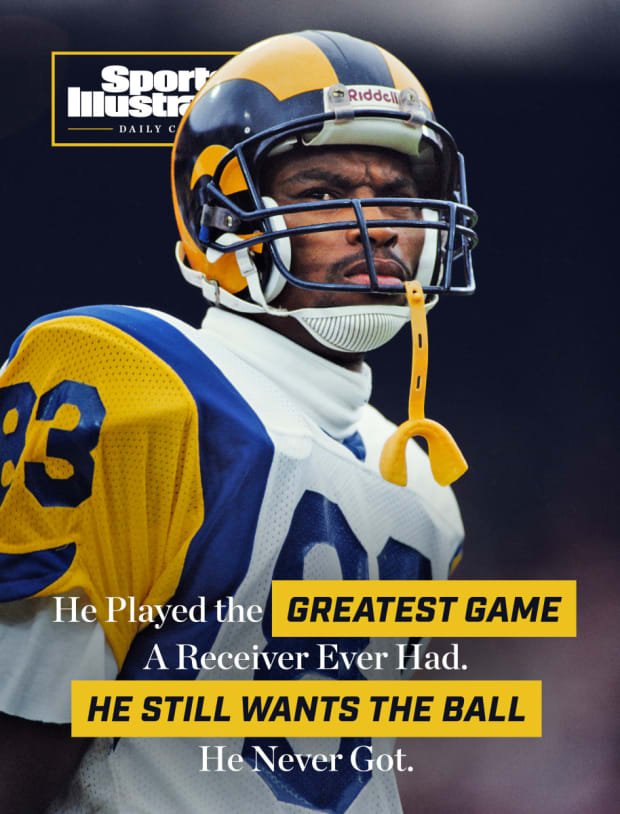

Some 2,200 miles east, Willie “Flipper” Anderson, sits in his Suwanee, Ga., home. He has a different job in a different sport. He remembers that November night in 1989, now half a lifetime ago. How could he forget it? He had the greatest single-game performance by a wide receiver in NFL history.

He’s not bitter that Everett, who had faced down the Saints’ vaunted Dome Patrol, one of the best linebacking corps ever assembled, got the game ball. But Anderson wants to make two things clear: He still wants that ball. And his old quarterback made him a promise.

In the autumn of 1989, Anderson was in his second year in the NFL. He was a 6-foot speedster, selected with the 46th pick of the ’88 draft, out of UCLA. And the nickname? It had nothing to do with any feats of showmanship. According to an SI profile from 1990, a distant cousin, Aunt Pearl, thought baby Willie’s crying sounded a lot like a certain TV-famous dolphin.

Anderson is universally described as quiet and humble. Everett says he would come out of his shell in the locker room or with people who knew him. “He was like the choir in the locker room,” Everett says. “When something was going on he would call it out. I swear to God even after all these years I can still hear him say, ‘Come on dog!’”

Adds Anderson: “I’m not really that big, so I had to show what I was expressing. I was more of a ‘show me’ person than a trash talker. I didn’t like to show guys up too much, but I did what I did.”

After racking up just 11 catches his rookie year, Anderson’s second season got off to an electrifying start. He was averaging an NFL-leading 30.7 yards per catch heading into the matchup against the Saints, a crucial Sunday-night game with the Rams one game ahead of New Orleans as the NFC West rivals jockeyed for wild-card positioning behind the powerhouse 49ers.

Paul Spinelli/NFL Photos/AP

In that era, before spread offenses became common across the NFL, teams ran pro sets that typically included two receivers. Henry Ellard, a two-time All-Pro who led the league in receiving yards in 1988, was the unit’s star—“There was no better receiver than Henry Ellard,” Everett says. Opposite Ellard was a mix of Anderson and Aaron Cox, the team’s first-round pick in ’88, taken 26 spots in front of Anderson.

The Rams liked their chances against the Dome Patrol, but disaster struck during the Friday practice. Ellard says that, while running a route with about 10–15 minutes left in the session, he pulled a hamstring. “I knew pretty much at that point I wouldn’t be able to play,” Ellard says now.

While the team held out hope that their star receiver would take the field, Anderson remembers Robinson’s initial reaction. “The one thing I think really spurred me on [in that game] was our coach himself,” he says. “Because when Henry went down, he looked to Aaron [Cox] and said, ‘O.K. Aaron, you got to step up,’ and he never really mentioned anything about me.”

Everett arrived at the Superdome on Nov. 26, 1989, three days after Thanksgiving, fully expecting Ellard to play. “We were like, ‘He’ll be ready, he’ll be ready, he'll be ready,’ because everyone plays hurt,” Everett says. “But right before the game, he’s like, ‘Dude, I can’t do it.’”

The quarterback calls the ensuing hours a “mad scramble.” Everett believes there’s a misconception that, in an instance like this, the Rams could simply plug Anderson into Ellard’s X-receiver position. But Ellard and Anderson, stylistically, were very different players. Everett says Ellard was “our Cooper Kupp type” while Anderson was more of an “over-the-top” deep threat. While Anderson thrived due to his speed, the X-receiver’s success was dependent on timing with the quarterback—Anderson had limited practice time there, and the pair’s chemistry was underdeveloped for that spot.

Then there was the Rams’ other problem: the quality of their opponent. “The Dome Patrol was the bomb, man,” Everett says. “They were legit. If they ever would’ve had some sort of offense they would’ve been Super Bowl champions year in and year out.”

The Pro Bowl linebacker group earned the “Dome Patrol” moniker thanks to the play of Rickey Jackson, Vaughan Johnson, Sam Mills and Pat Swilling in an aggressive, blitz-happy scheme. Combined, the group had 18 Pro Bowl selections during their time in New Orleans.

New Orleans expected Ellard to play. But, according to Robert Massey, then a rookie starting cornerback, no matter who lined up that day, the game plan would remain the same. Massey, now 56 and the coach at Winston-Salem State University, recalls the scouting report saying that, in addition to Ellard, the Rams had “two speedy quick kids” in Cox and Anderson.

Things started as expected for the shorthanded Rams, with the Saints’ pass rush breathing down Everett’s neck. The Superdome crowd presented a major challenge, with tight end Pat Carter and Anderson both saying nobody could hear the snap count all night. “We could barely hear each other,” Anderson says. “I could barely hear what the play was and never heard the snap count all day; I was looking at the ball. You could be a foot away from each other. You really had to yell into someone’s earhole to really talk. That Superdome was really rockin’.”

L.A. went into the locker room trailing 10–3 at halftime. Anderson, though, gave the team a glimmer of hope with his four catches for 85 yards in Ellard’s stead. But the Rams struggled overall—Everett was 7-for-18 for 111 yards and an interception and had taken two sacks. “We really couldn’t get in sync early in that game … but we did later,” Everett says, punctuated with another laugh.

Meanwhile, the Saints saw no reason for significant halftime adjustments. “It’s a simple game—if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” says Massey. “We had the lead at halftime, why would you change? Everything was working. Again, it was chess. It was their turn to make a move. And they did and things started working for them.”

Anderson started the second half with a quick catch for small yardage on the left sideline, then made one of the biggest plays of the night. New Orleans sent the blitz and Everett, on a five-step drop, hit Anderson in stride running up the right sideline. Anderson had been in a one-on-one matchup with Massey on the play, and offensive coordinator Ernie Zampese smelled blood in the water. The Rams took advantage of the fact that the Saints weren’t following Anderson, allowing them to dictate matchups, often picking on Massey. “They were trying to cover for the rookie [Massey],” Everett says. “We knew we were going after the rookie. We were like, ‘O.K., you got an option to go somewhere, let’s go after Massey.’”

NFL Photos/AP

Yet the Rams couldn’t put points on the board. They had taken over at the New Orleans 19 after a deflected interception on the first play of the second half, but that possession ended with a partially blocked chip-shot field-goal attempt knuckling wide left. Three plays after that 50-yard Anderson reception, Everett was sacked out of field-goal range. The Rams caught another break when the ensuing punt was muffed, giving them the ball back on the Saints’ 8, but they came up empty again, Everett taking a sack on fourth-and-goal.

A few minutes later, Anderson beat Massey for his seventh catch of the game, but Massey won a battle two plays later with his second interception of the game. On the next drive, Anderson’s 14-yard catch moved the Rams into scoring position, but three plays later Rams running back Greg Bell lost a fumble at the New Orleans 20. As Robinson told reporters after the game, “I wasn’t sure we were ever going to score in another football game as long as I lived.”

By the time Los Angeles got the ball back, it trailed 17–3 with only 4:40 left. Anderson, at that point, had eight catches for 171 yards.

“I gotta admit, most of his career [he’s] like ‘Dog, I’m open! Hey dog, I’m open!’ Which receiver doesn’t come back to the huddle and say ‘I’m open’?” Everett says. “But on that day, I was like ‘I believe you.’”

The third play of the drive is what sparked the comeback. Looking back, both Everett and Anderson say it was their favorite moment of the night, known now as the “Jumbotron catch.” But the thing is, it wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

The play called for Cox to come across the middle of the field as the primary read; Anderson’s job was to run a clear-out route. There’s a jumbotron above the end zone—Anderson, believing he was out of the play, stole a split-second glance at it. “I’m like, ‘Oh, he’s gonna throw that to me.’ It was the helmet catch before the helmet catch.”

Everett launched a dime from midfield to a streaking Anderson, again matched up one-on-one with Massey. He beat the rookie to the inside and snagged the ball from over the top of him at the 8-yard line, falling forward to the 4, a 46-yard gain.

“He was definitely just clearing out,” Everett recalls. “It was probably one of those balls that you complete like 5% of the time. But that was probably a Brett Favre–type—‘I’m gonna take this shot and I feel pretty good,’ and it worked out.”

The pass gave Anderson nine catches for 217 yards and set up a five-yard touchdown run by Buford McGee.

After the Rams’ defense got a stop yet again, Everett and company had the ball at the Saints’ 40 with 2:04 left. A sack and a holding penalty made it second-and-32, at which point Everett hit Anderson over the middle for 25 yards. After L.A. converted on third down, Anderson picked up another 14 yards on a first-down reception on the left sideline, this time between two defenders, at the New Orleans 15. On the next play, the Saints showed blitz and sent six. Anderson was lined up on the right side of the formation, singled up against Massey. There was no hesitation; Everett took a three-step drop, leaving his feet in the face of the rush like he was shooting a fadeaway jumper. Massey failed to turn around, the pass floating past the left earhole of his helmet and into Anderson’s hands. The PAT tied the game with 58 seconds left.

After forcing a quick Saints three-and-out, the Rams actually had a chance to end it in regulation. Starting at their own 41 with no timeouts and 22 seconds left, Everett hit Anderson for 24 yards, and L.A. clocked it, but Lansford’s 52-yard attempt went wide left as time expired. Headed into overtime, Anderson had 13 catches for 296 yards.

Anderson thinks it was around this time he became aware of the single-game receiving yardage record, set by Kansas City’s Stephone Paige four years earlier. Anderson was 13 yards away. It was Ellard, the injured star, who pulled him aside to let him know. “Being the great guy that he is, he came to me and told me, ‘Hey, man, you’re getting close to the record,’” Anderson says. “He was the one who sniffed it out. I never really thought I was gonna get a record; I didn’t even know what it was.”

He drew a 35-yard pass interference penalty on the Rams’ first possession of overtime, but Anderson was quiet until a third-and-6 from the L.A. 47. Working from the right slot, matched up against Toi Cook, he ran a drag route and made the catch well short of the sticks as he accelerated away from Cook. The DB clipped his heel and tripped him up, but not until Anderson had picked up 14 yards, a first down, and an NFL record.

On third-and-11 from the Saints’ 40, with two receivers to the right of the formation and two backs staying in to protect against the blitz, Anderson beat Milton Mack down the left sideline, hauling in a floater from Everett and holding on through a punishing hit from safety Dave Waymer. Anderson stayed down for a few moments, but for the first time all night, he could rest. The 26-yarder had pushed him to 336, and set up Lansford’s game-winner on the subsequent play.

“That was probably the grandest moment of my whole NFL career,” Anderson says. “I love New Orleans; I still have stock in that Superdome. It’s still making me money until today.”

Cook takes exception to the idea that New Orleans’s man coverage led to its downfall. “A lot of those catches, at least from what I’ve seen on the highlights, were contested catches. It wasn’t like he was running butt-naked free,” he says. He also feels like Anderson received too much credit while Everett was snubbed. “He had Jim Everett. It’s like being the caddy for Tiger Woods when he’s hot,” Cook continues. “Flipper was the recipient of a great day. Great throws under pressure. Everything worked out in his favor. The fact that Henry Ellard wasn’t there so they had to go to him and at the time, it wasn’t like, ‘Hey, we’re gonna put Toi on him,’ or ‘Hey we’re gonna put Robert [Massey].’ We didn’t have anybody; we didn’t have Deion [Sanders] to go put on Flipper.”

Massey, on the other hand, has a far lighter viewpoint of that game than he did at the time. He says the record-setting performance “couldn’t have happened to a better guy. … He was a mild-mannered guy who worked hard, had good hands, good speed—let me not say that: He could f---ing fly.

“When I joke about it, I tell guys I’ve been in a game where they threw 51 times and 55 of them were at me,” he adds.

Everett finished the game with 29 completions on 51 attempts for 454 yards and that single touchdown, to Anderson. He also absorbed six sacks and was intercepted twice, both times by Massey.

For the next 24 years, Anderson slept peacefully knowing no player had gotten close to his all-time night in New Orleans. Until 2013 in Detroit, when Calvin Johnson started to cut up a Cowboys secondary like an overeager butcher. “That was one of the weirdest days of my life,” Anderson says.

At the time, Anderson was on the golf course, leaving his phone behind in his car. When he finished, he returned to—he estimates—50 to 75 text messages saying that his record was in danger. He rushed home, getting back in time for the third quarter. Johnson’s 22-yard catch with 14 seconds put Detroit, trailing by six, on the 1-yard line. It also gave Johnson 329 yards on the day. The Lions scored on the next play and, when the PAT went through, it virtually guaranteed Detroit wouldn’t get the ball back; Johnson’s historic day settled for second place.

“I wouldn’t say I was rooting against him,” Anderson says. “But I’m still glad that I have it.”

His name is still etched in the record books, even though he never earned All-Pro or Pro Bowl honors. The Saints game accounted for nearly 30% of his yardage in 1989, his first of back-to-back 1,000-yard seasons. He played for the Rams until 1994, then made brief stops with the Colts in ’95, Washington in ’96 and then, in ’97, the Broncos, earning a Super Bowl ring, though he didn’t catch a pass that season. When his playing career ended, he pivoted to a different pastime.

Now, living in Suwanee, he follows a strict schedule to make it to games on time. Anderson says getting fined in his past life helps him stay stern in his time management. He starts with a shower at 3 p.m. Then he gets dressed before he packs his striped uniform and hops into his black Suburban to drive to the assignment for the day. Games usually start at 6 p.m.; he makes sure he’s there an hour early.

Once at the high school, he changes and jogs on the court 15 minutes before tip-off. Typically, he’s the head referee and will talk to his crew to discuss what kind of players and coaches they’ll be officiating for the night. Then, three minutes before game time, he’ll talk to each team’s respective captains to let them know he wants a clean and fun game. Then they’re off.

He’s in his 19th year as a high school basketball referee. At 57, he says he does it to stay young and in shape. The kids who play in the games are completely unaware of his past life and frankly would never believe he owns the NFL’s all-time receiving record for a single game. “To them, I’m known as Mr. Ref,” Anderson says. “If I told them that I was a former football player they probably wouldn’t even believe me. No one knows.”

Paul Spinelli/NFL Photos/AP

Meanwhile, that game ball still sits on Everett’s mantle. It reads “Game Ball Presented to Jim Everett. Personal Best As A Ram 29-51 454 yards,” with the final score, 20–17, at the bottom. As for that promise, Anderson says he’ll give it up, on one condition.

“Well, he said it to me—if you can get this on record—he said I can have it once he dies.”

It doesn’t matter to him if the quarterback’s statistics are scrawled on it. Just like on a November night 33 years ago, Flipper Anderson wants his quarterback to get him the ball.

• The Politics, Economics, and Evolution of Long Snappers

• Why Philly Can’t Get Enough of Jalen Hurts

• Robert Griffin III Is ESPN’s Next Big Star

• When Phony Environmentalism Comes to Sports