He's not the new Babe Ruth. He's more amazing than that.

The phone of Ippei Mizuhara, friend and translator to Shohei Ohtani, buzzed with a text from Angels manager Joe Maddon late on the night of Aug. 18. This is what passes for the determinative daily diagnostics of whether Ohtani can physically withstand the rigors of pitching and hitting in the same season unlike anyone before him.

“How does he feel?” Maddon texted.

This diagnostic check carried more than the usual curiosity about whether Ohtani could DH the next day or required a day off. Ohtani had just played the most Ohtani game of all Ohtani games: eight innings of pitching with eight strikeouts while hitting his 40th home run in a 3–1 road win over the Tigers.

Ohtani hit his home run 110 mph and 430 feet off a breaking ball in the top of the eighth, making him only the second hitter this year to hit a breaking ball that hard and that far in the eighth inning.

In the bottom of the inning, Ohtani threw a fastball 98.1 mph to strike out Victor Reyes. Only two other starting pitchers this year had registered a strikeout with a pitch that hard that late in a game: Gerrit Cole and Jacob deGrom.

If you had only nine minutes, five seconds to understand why Ohtani, 27, has pulled off the most amazing season in baseball history, this was your window. Eight innings deep into a mid-August night, Ohtani hit one pitch 430 feet with his last swing and threw another 98.1 mph with his last fastball. Cliffs Notes to an epic.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated; Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

“I’m old school, or whatever you’d like to call it,” says Angels bench coach Mike Gallego. “I don’t talk this way about anybody. But what he’s doing this year you will never see again.

“Unless it’s by Ohtani.”

Upon receiving the text, Mizuhara checked with Ohtani. He had thrown 90 pitches when Maddon replaced him with closer Raisel Iglesias to start the ninth. After the game Ohtani iced his elbow and shoulder while he met with 27 reporters over Zoom before returning to the team hotel. The next game would be here in about 13 hours. Maddon waited on a reply text.

“It’s a very easy method,” Maddon says. “I told him he is in charge of this. I asked him for absolute honesty, and he has gotten mine in return. Me, [GM] Perry [Minasian], Shohei and Ippei, we all sat down in spring training and decided there would be no specific limitations to pitching and hitting. Shohei explained to me that he would let me know. When his legs felt tired, that’s when he may need a day. That hasn’t happened.”

This would be the biggest test yet: Could Ohtani play the day game after a night game after the longest outing of his major league pitching career? Maddon’s phone buzzed. It was Mizuhara with a reply.

“He is all good for tomorrow! Thank you for taking him out there Joe!! Great win.”

Mizuhara closed with a trophy emoji.

Done. Ohtani decided he was playing, just like that.

“There are no controls,” Maddon says. “He owns the joystick.”

It is a far cry from how the Angels handled Ohtani in past years, when they used complex data to monitor his energy level, sleep, soreness and nutrition—right down to how many times he dove back to first base on a pickoff attempt—to decide when he should play. Any deviation as little as 5% in his energy level would cause the Angels to issue a “yellow light” of caution on his use.

“They broke the glass house,” Gallego says. “They let him go play baseball and don’t hold him back in any manner. Because of that, he feels the game.”

Ohtani threw 77% strikes against Detroit. He threw only 21 balls to 28 batters. It was only the second time this season a pitcher navigated eight innings with eight strikeouts on 90 pitches or fewer. After the other occasion, the pitcher, Zack Greinke of Houston, took five days of rest. “It takes two or three days for a normal pitcher to recover from the stress,” Gallego says.

Ohtani batted leadoff the next afternoon. He had two hits, two walks, two runs and a sacrifice fly. At 6' 4" and 210 pounds, he beat out his 14th infield hit. In just one of the many amazing-but-true Sho-stopper stats, by the end of August, Ohtani had hit the most homers 430 feet or more (15) and had the second-fastest home-to-first time (4.10 seconds), behind Atlanta second baseman Ozzie Albies, who is eight inches shorter and 45 pounds lighter.

Babe Ruth was the benchmark for two-way players, rare as they have been. But Ruth never was a full-time two-way player for more than three consecutive months; he did it for a stretch in the 1918 season and again in ’19. Ohtani is six months into his double duty. And yet, the wonder of Ohtani isn’t merely that he is doing the two disciplines. Instead, it’s that he is adding elite performance and beautiful aesthetics to this skill show. He is playing at such a high level that he is a virtual lock to be named American League Most Valuable Player, and he deserves consideration for the Cy Young Award as the league’s best pitcher.

Entering play Tuesday, Ohtani has 44 home runs, one behind Vladimir Guerrero Jr. for the most in the majors. If Ohtani wins the home-run race with Guerrero, he would become only the fifth player to lead MLB outright in homers and steal 20 bases, which would put him in the company of only Willie Mays, Mike Schmidt, Jose Canseco and Alex Rodriguez. Ohtani also is on pace to become only the ninth pitcher to strike out at least 10 batters per nine innings with a winning percentage of at least .810 over 20 starts or more.

Raj Mehta/USA TODAY Sports

Combine the two disciplines, and Ohtani occupies a solitary place in the Venn diagram of baseball history. He is the only player to strike out 100 batters and hit more than nine home runs, the only All-Star named to the game as a pitcher and a hitter, the only All-Star pitcher (he started and won the game) to bat leadoff, and the only player since Statcast tracking began in 2015 to hit six 500-foot home runs in the All-Star Home Run Derby—the day before he threw a fastball clocked at 100.1 mph in the game.

“I was pretty amazed by him last night,” Tigers manager A.J. Hinch said the morning after the Aug. 18 extravaganza. “To see it in person is something I’ll always remember. He was pretty artful in his pitching approach, mixing his pitches early—incredible strike throwing—and then leaned on velo late in the game. His stuff got better as the outing went on.

“His power is enormous. He hit the most majestic homer I’ve seen in a while. I’m mostly amazed at the ease he plays with. He doesn’t try too hard or give the impression that he is stressed physically or mentally. Completely under control. His conditioning has to be elite.”

Ohtani endured injuries and surgeries to his elbow and knees in his first three seasons. After last season, with rehab work finally behind him, he strengthened his body, especially his lower half, while changing his diet based on blood work to determine what foods best fueled him. He felt so good that he led the charge at that spring training meeting to finally discard the governors on his workload.

Freed, the caged bird soared. His two-way duty is a labor of love. He had decided when he was 18 years old to be a two-way player. He told MLB teams when he was a free agent that a condition of his signing was to be a two-way player. The narrow American mind that equates specialization with advancement completely misses the essence of Ohtani when it suggests he should pick one discipline and max it out. Ohtani is successful precisely because he is not specializing. You should no more encourage Ohtani to forsake one discipline than you would ask Springsteen to knock off either the singing or the songwriting. His heart fills with joy from doing both, and it is in that Zen-like place when all of us are at our best.

“He’s got a great sense of humor and is always laughing and joking easily,” Maddon says. “Compared to last year, it’s night and day. Last year he was not enjoying himself. He always appeared to be somewhat stressed. This year is exactly the opposite. There is a joy about his game.”

People crowded around the Comerica Park visitors’ bullpen to watch Ohtani warm up for the Aug. 18 start.

“When he warms up people always get close and want to watch his routine,” Angels pitching coach Matt Wise says. “It’s an event. I definitely have taken some moments where I step back and just go, ‘Wow.’ ”

The spectators had better not dally. Ohtani first takes batting practice in an indoor cage, staying off the field to conserve energy and avoid the regimented schedule of on-field batting practice. Then, on nights he is pitching, he heads to the bullpen. He warms up by throwing balls of various weights against a wall as Mizuhara measures their speed to make sure he is reaching the proper exertion level. When he climbs the mound, Ohtani throws only about 20 pitches, about half what most pitchers throw.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

“He really sets the tone for himself,” Wise says. “He definitely gets down to the bullpen a little earlier than most pitchers because he is also hitting first or second. He’s pretty used to it. He throws around 20 pitches, takes a nice stroll to the dugout, puts his helmet on and gets to work.

“The way he is saving energy and effort, it’s incredible. Even his bullpens [between starts] are very, very light. [They] are just to feel the slope of the mound with the ball coming out of his hand.”

The genius of Ohtani as a pitcher is in his artistry, a compliment rarely afforded someone who can throw 100 mph. Wise and catchers Max Stassi and Kurt Suzuki will review opposing hitters with Ohtani and Mizuhara before a game. “He’s extremely intelligent, open to information, and his memory is very strong,” Wise says. But when the game starts, Ohtani goes more by feel than by script.

Against the Tigers, for instance, he averaged 93.5 mph with his fastball in the first two innings and 97.8 mph in his last three. He complements it with four secondary pitches: curveball, slider, cutter and a split-finger fastball that acts as his changeup. It is thrown about 10 mph slower than his fastball with 34 inches of vertical drop.

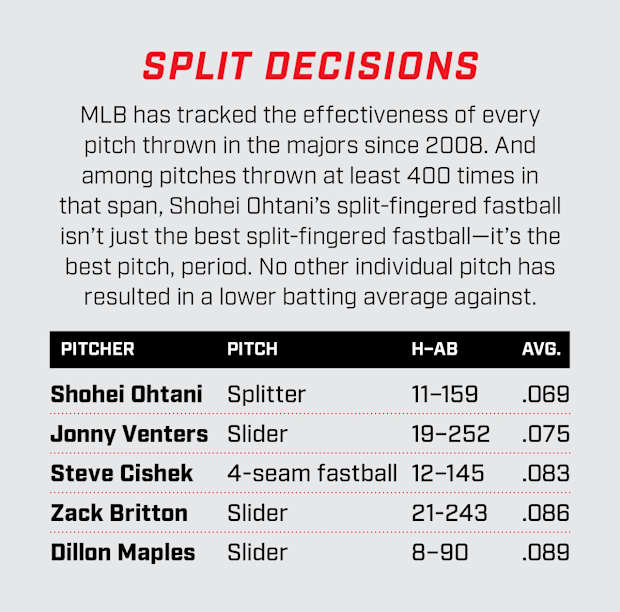

Of all the pitches thrown at least 400 times by all the pitchers since Ohtani joined the majors, his splitter is the most difficult pitch to hit. Batters have hit just .069 against Ohtani’s split, with only 11 hits over four years—none of them home runs.

The sharpness and touch Ohtani exhibits on five pitches are astounding given that he can devote much less maintenance to his mound work than pitcher-onlys. Ohtani throws a baseball the way da Vinci wielded a paintbrush. There is a serene beauty, an ease of movement and effort, in the brushstrokes of his craft. And there is a brilliant deception in the technique.

Ohtani is borrowing from da Vinci’s technique of sfumato, the exquisite blending of shades and colors that are almost imperceptible to the human eye. Translated literally from Italian, it means “vanished” or “evaporated.” Sfumato is what puts the mystery in Mona Lisa’s smile—and the deception in Ohtani’s pitches.

Asked what impresses him most about Ohtani’s pitching, Wise says, “His ability to throw such a wide range of fastballs. He’s effective through the range of about 90 to 100, and he throws them effectively in the zone. That to me is incredible. Most guys can’t do that. He can dial it up whenever he wants.

“I have a 13-year-old son. And I tell him, ‘If there is a delivery to emulate, it would be his.’ He throws pretty. He’s a large person that moves like an elite athlete. He is an elite athlete. His delivery is very fluid. To me it’s about as perfect as it gets.”

Ohtani was a competitive swimmer growing up. He has the broad shoulders, narrow waist, long levers, lean strength and freakish flexibility of Michael Phelps. After Ohtani throws a pitch, his right hand slaps against the back of his left oblique, an ideal, maximum range of deceleration that saves wear and tear on his arm and shoulder—like easing a plane to a stop after landing on a long runway rather than slamming the brakes on a short one.

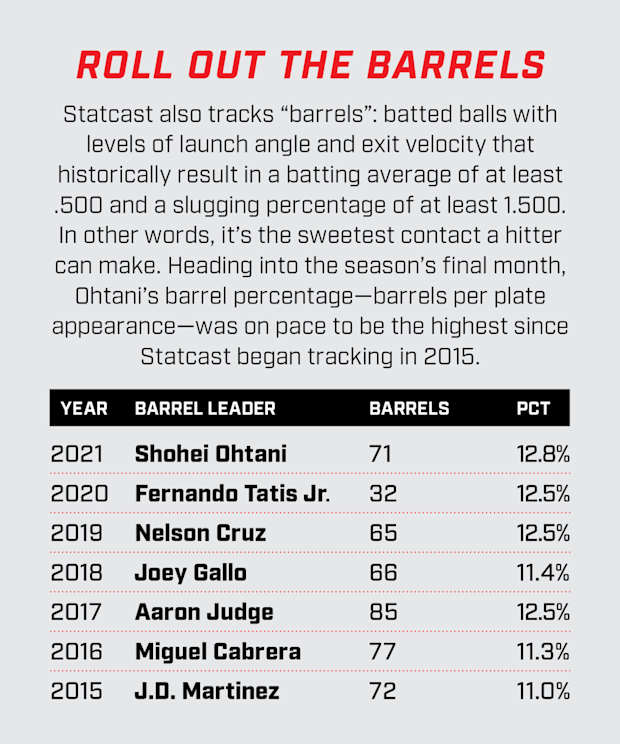

As a hitter, Ohtani starts and finishes with two hands high, with the barrel of the bat tapping the back of his right shoulder on his majestic finish. In one midsummer stretch, Ohtani became the first hitter in American League history to hit 16 home runs in 21 games. More than one out of every three fly balls he has hit this year has been a home run (34.4%, the highest rate in the AL).

“What we’re looking at is something special for the world to see,” Gallego says. “At the plate he’s Barry Bonds. When Barry was hitting his 73 home runs, every swing he took, everybody would take a deep breath. Either he just missed it, or it was a home run. That’s how this guy is. I never had that feeling with another hitter, other than Bonds.

“And yet this guy is also a Cy Young candidate. There’s nobody close to him. We’re comparing him to Babe Ruth, but I don’t think even that does him justice. He’s the best player I’ve ever seen on a day-to-day basis, and I’ve seen some Hall of Famers, like Rickey Henderson. To be able to do what he’s doing right now, and to do it every day, it blows me away.”

Ohtani is good for business, and not just the T-shirt business. A 2021 Ohtani All-Star jersey autographed by Ohtani (but not worn by him) sold by MLB Auctions for $130,210, setting a record for the highest-priced item sold in the two decades of the service. The previous record was set just three days earlier—for an Ohtani game-worn Angels jersey that went for $121,800.

In a 60-day midseason window, MLB generated $450,000 in new sponsor deals directly related to Ohtani, most of which were tied to the All-Star Game broadcast in Japan.

In Japan, MLB games with Ohtani rate 256% higher than non-Ohtani games. Social media posts featuring him have a 267% greater reach.

In Taiwan, Facebook posts featuring Ohtani generate 921% more engagement than non-Ohtani MLB posts. Angels games account for 30% of the games shown there and perform 80% better than games without him.

In Korea, his posts get 188% more likes.

In addition to the plethora of T-shirts, you can buy Ohtani birthday cards (IT'S SHO BIRTHDAY), coffee mugs, pillows, hats, hoodies, beach towels, ornaments, laptop sleeves, phone cases, water bottles, earrings, throw blankets, tote bags and, in keeping with the times, face masks. One hundred and two years after the Babe quit the two-way gig because he found it too tiring, Ohtani is a true international brand and—if only the Angels could build a playoff team—the face of baseball.

Mary DeCicco/MLB Photos/Getty Images

“He comes across as very authentic,” Hinch says. “I loved his act watching the All-Star Game from afar. He’s such a good player to celebrate.”

Ohtani smiled through what had to be an exhausting two days in Denver for the All-Star festivities—the Derby, the game, one interview after another. At one point while snaking through a pre-Derby crowd ringing the field, Ohtani was bumped inadvertently on the shoulder by a heavy, shoulder-mounted television camera. Ohtani quickly turned and asked the camera operator whether he was all right. He earned $150,000 from the Derby, all of which he gave to 30 Angels training and front office staff members.

He is fastidious about keeping his surroundings neat; he picks up bits of loose trash in the dugout and on the field. He casually flips the ball to himself on the pitcher’s mound, just as you might see a Little Leaguer do. He makes sure to politely greet the opposing catcher and home plate umpire when he takes his first at bat of a game.

“He goes out there with these huge expectations on him, and he’s just playing a game for the Angels,” Maddon says. “Tokyo is New York. He plays in a large market on the West Coast. Every kid wants to watch him and do what he does. And yet he handles it all so well.

“The guys on the team really love him. They appreciate his abilities. But they love him because he is so respectful and humble. When you hear his high-pitched giggle in the dugout, everything is right in the world.”

Japanese proverbs are works of art when painted with Zen calligraphy on mulberry paper. The artist becomes one with the meaning the characters create.

Americans guffaw over punny T-shirts.

The proverb about the frog in the well is about how the limits of experience limit us. The frog in the well has no idea about the vastness of the ocean. The message is to get out into the world.

In baseball, to get outside the well is to break from the American way of specialization, a confinement in which kids as young as 12 years old become pitcher-onlys, in which the average relief pitcher throws just 19 pitches per appearance, in which teams use 35 pitchers per team per year, and in which Ohtani, when he reached 100 innings in mid-August, had thrown more innings than 89% of all pitchers.

It is tempting to think Ohtani is changing that world. But to believe that this is the start of something—that kids wearing SHOHEI OHTINY onesies will grow up in a world with more two-way players—is to believe that there are others who are this talented, this hypermobile, this driven, this humble, this joyous.

“Not that I’ve seen. It’s hard to imagine,” Maddon says. “Not with that combination of skill on the mound and at the plate. And don’t forget the speed.

“What he has done is he has started a trend of more people believing they can do it. He’s knocked down that barrier. In professional baseball there might be some more openness to try it with different people. But you’re not going to see it. Not like this. This is more than a once-in-a-lifetime player. This is a once-in-a-century player—or more.”

Abbie Parr/Getty Images

What Ohtani is doing is so rare that there is an underlying fragility to it. What happens when The Most Amazing Season There Ever Was turns plural? The answer is informed by Ohtani’s physique and fitness and by his joy to both pitch and hit. “You see it in how he runs, how his body moves,” Maddon says. “This is a big man, but he runs at a really high level, like an NFL wide receiver. There is fluidity in his body. There’s no tension. He competes freely.

“I believe by doing both he’s not going to get overloaded or overwhelmed or grind too hard on one thing. Once a mind expands it does not revert to its original shape. Doing more things, by not bogging down the mind with one thing, lends itself to discipline.”

Says Gallego, when asked whether the Year of Ohtani is sustainable: “Why wouldn’t it be? The guy’s in great shape. He’s as strong as an ox and runs like a gazelle. He’s a superhero.”

Then again, why even ask the question? We are watching Ohtani, but are we paying attention to him? Because if we are, we know that he is not only gifting us with the most amazing season ever, but he is also reminding us of the wisdom and beauty of staying in the present tense. Only when we get outside the well do we experience the true vastness of the world. Limits fall away.

More MLB Coverage:

• Blue Jays' Bashing Offense Is the Answer to MLB's Woes

• How MLB Squashed its Fake-Memorabilia Problem

• Who Is the Next Miguel Cabrera?