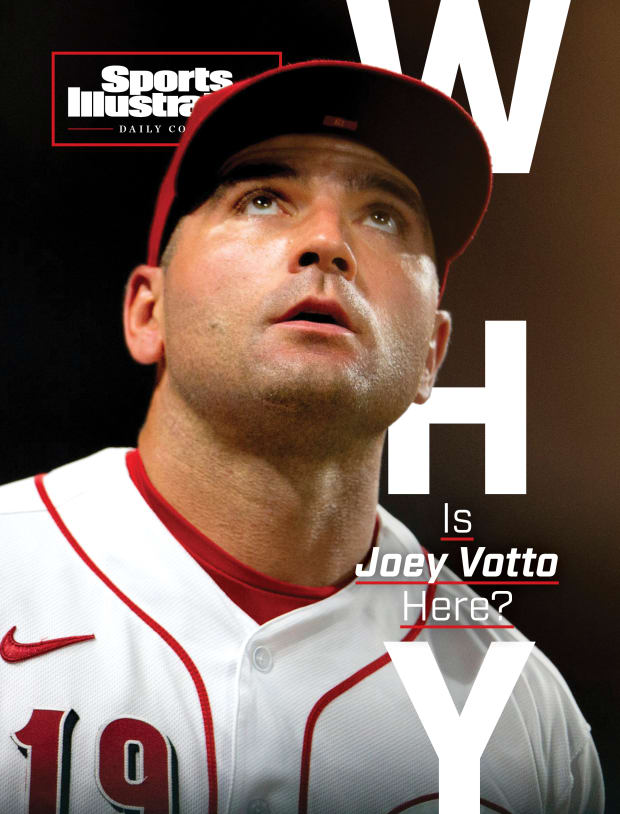

He is launching balls like never before. But his late-career turnaround is about more than just letting it rip.

Why is Joey Votto here? For a long time, when he dug into the left-handed batter’s box, the answer was simple: He wanted to be perfect.

And for a long time, he just about was. He led the league in on-base percentage seven times in his first 10 full seasons. From 2010 through ’14, Votto infield pop-ups were rarer than perfect games. All that precision has made for a very valuable hitter: Since the Reds’ first baseman debuted in ’07, only Mike Trout and Robinson Canó have accrued more WAR. Votto won the National League MVP award in 2010 and came two down-ballot votes from winning it again in ’17.

Now, two weeks past his 38th birthday and with less than two weeks to go in the season, he is unspooling his best offensive year since then. In July, he became the eighth player ever to homer in seven straight games. His 33 dingers, including two on Monday, are four short of his career high. He has collected his 300th home run, 1,000th RBI and 2,000th hit. He is doing his best to will the Reds to a wild-card berth, hitting .389/.593/1.000 with three home runs over the past week. (They sit four games behind the Cardinals.) His teammates sport T-shirts that read VOTTO STILL BANGS.

Occasionally he will turn to a coach in the dugout. “I’ve got this guy,” Votto will report. Every time, they swear, his next at bat ends in a home run.

He is almost unrecognizable, with a new batting stance, a new approach and a new joy. He is trying to fulfill a promise to his father and another one to himself.

Albert Cesare/The Enquirer/USA Today Network

Why is Joey Votto here? It was Aug. 25, 2020, and he couldn’t stop asking himself that question.

Some 20 minutes earlier, he knocked on the door of Reds manager David Bell’s Milwaukee hotel room, summoned there by text. Bell delivered the worst news of his star’s career: Votto was getting three days off.

Votto was incensed. Sure, he had gone 0-for-4 with four strikeouts that day to bring his average to .191, fifth worst among players with that many plate appearances. He was making weaker contact than all but four other regulars. The scouting report had become simple: Let’s see whether he can beat us. But he believed he could fight through it.

Bell disagreed. Hence the three days off. Or, as Votto insisted on referring to it, the benching. “I was really angry,” he says now. “I was insulted.” He lobbied passionately for his spot in the lineup before trudging back to his room.

The coaches, who had convened a few times to discuss the decision, expected him to be frustrated. They did not expect the level of anguish he felt.

“I’ve never had my heart broken,” he says now. “And it felt like a genuine heartbreak. I felt devastated. I felt humiliated. It was kind of—not beyond a heartbreak, but kind of, because it's all I do in life. It's everything.”

He had never been benched before, not as a minor leaguer or even as an amateur. What am I doing with my life? he thought. Why am I here in Milwaukee, if I'm not able to play? Why am I here? Why am I in this city? Why am I riding these planes? He hates the word sacrifice as it relates to his job. He has made a choice to pay a steep price.

“I don’t want to say I’ve put my social life on pause, my personal life, but truly, I have,” he says.

Kyle Ross/USA TODAY Sports

Now he questioned whether he wanted to keep paying it. He had felt similarly before. In 2018, as he was assembling an All-Star season, he would sometimes find himself sitting on the bench, wondering whether he wanted to do this anymore. For the third straight year, he led the league in on-base percentage (.417), but he never felt comfortable. And his body hurt. The deep crouch, the stiff stance, the long plate appearances—it all wore on him. His knees hurt. His back ached.

“There's people out there with jobs that are life threatening and I’m playing ball, but it really was a painful style, physically painful, and that physical pain—I really did not get excited about working,” he says.

So he slumped in the dugout during games, trying to decide whether to keep working. He continued struggling with the decision at times in 2019. He mentioned his misgivings to no one.

“I didn’t want to speak it into existence,” he says.

When the pandemic shut down the 2020 season, he figured the break would benefit him. I’ll perform well in an abbreviated season, he told himself. Worst-case scenario, I’ll perform O.K.

“And then it was a total mess,” he says.

So, trapped in his hotel room in Milwaukee, he decided something had to change. He promised himself he would find a way to enjoy his job again. What would I find satisfying? he wondered. Like so many hitters before him, the answer was: launching bombs.

He had been an aggressive swinger as a kid, but as an adult he sought perfection. He loved being the guy who played 13 years in the majors before popping out to first base. As he aged, though, it became harder to sustain that style. Any slump left him anxious about how he would make up for it: When your strategy is perfection, you can’t save a disappointing season with a big week.

Then his power disappeared. He hit 12 home runs in 2018 and 15 in ’19. “That's unacceptable for me,” he says. “I'm a guy that has the skills to hit the ball hard. And I decided, You know what, I really want to start tapping into that part of my game.” He wasn’t sure it would work. He thought he would be late on fastballs. But he was so tired of being miserable that he decided to try it.

Unlike so many hitters before him, one of his first steps was to call a golf instructor for advice. The pro suggested that he try to generate power by transferring his weight toward the pitcher. Votto had long modeled his style after Barry Bonds, who more or less stayed fixed in one place, then rotated his body. But Votto could no longer create enough force that way. He began watching video of Babe Ruth and Stan Musial and Mickey Mantle. Holy cow, Votto thought. They jumped at the pitcher.

He stalked around the ballpark in his shorts, channeling his frustration into batting practice and lifting weights. “I think he was mad at anything that walks,” says game-planning coach Jeff Pickler.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, Votto spent the games he wasn’t playing in the stands. From that side angle, he watched as his teammates slugged home runs. He also noticed how aggressive they were, how willing they seemed to swing and miss, how sometimes they would mis-hit a ball and it would still fly over the fence.

What are you doing, Joey? he thought. You can do that. This is ridiculous.

He scrapped perfection. He decided to hit home runs and have fun. He stood up straight in the batter’s box and kept his top palm pointing upward. Since he returned to the lineup on Aug. 29, only five players have hit home runs more often than Votto. And he says he has never had more fun.

David Banks/USA TODAY Sports

Why is Joey Votto here? His deal with the Reds will take him through 2023, his age-39 season. He will turn 40 that September. If the team picks up his option, that would be 22 years in the organization. He has played for more fifth-place clubs (six, including four straight) than playoff teams (four). He has never advanced out of the Division Series. He has never played on a club with a top-third payroll. Yet he negotiated a no-trade clause, and he has never considered waiving it.

He gets this question a lot. He has never been able to provide an answer good enough to make people stop asking.

“I like that I can work with steadiness,” he says. “It’s the simple things. It’s hard to explain. It's like, I know when I'm driving to work, there's not going to be traffic. I know that when I'm done work, I'm not in the country, per se, but I'm in the woods. It's close to the stadium. I love that when we do well, there's some support pretty quickly. I like my locker, the uniform, the people I work with. First and foremost, the people I work with. It's been more or less the same group since I came into the league. I like the familiarity. I like that I can be my best self here. Yeah, I can be the best version of me here, which is all I think I could ever ask for.”

He says he hopes his legacy will be of a player who had consistent success and walked away with dignity rather than limping offstage. He likes, too, the idea of retiring with the team that drafted him. He loves the NBA enough that, midway through his MVP season, he received permission to leave the team for 20 hours or so to watch Game 7 of the Finals in person. (His Lakers won.) But the era of the superteam has put him off the league. He does not just think Kawhi Leonard should not have left the Raptors—he thinks he should not have left the Spurs.

“Seeing certain players join certain teams, basically throwing off the entire power dynamic, more or less removing any chance of any other team sharing in success, I just—no,” Votto says, adding that he is speaking as a fan.

Cincinnati fans seem to agree. Says Rick Walls, the executive director of the Reds Hall of Fame, “He’s the one that stayed.”

Kareem Elgazzar/The Enquirer/USA Today Network

Why is Joey Votto here? Chris Denorfia wondered that when they reported for the 2002 rookie-level Gulf Coast League Reds. Denorfia was 22, a senior sign from Division-III Wheaton College, but even he had more high-level experience than the Canadian teenager standing in front of him, bashfully admitting that he’d never seen a fastball harder than 83 mph.

The kid had been a second-rounder, and he put on a show in batting practice, but even in 2002, the pitchers in rookie ball threw 95, and Votto couldn’t catch up.

“I think he spotted the league about 30 at bats where I don't know if he put a ball in play,” says Denorfia.

But every day, before and after workouts, Votto shut himself in the batting cage. Once, Denorfia walked in there and saw him drenched in sweat, staring at one of those old Iron Mike pitching machines that doesn’t need a coach to feed it. There were some 200 balls on the floor behind him. Votto wasn’t swinging. He was just tracking the balls with his eyes, trying to learn timing.

“I don’t know big leaguers that would do anything like this,” says Denorfia, who played 10 years in the majors and now tells this story to the Double A prospects he manages with the Hartford Yard Goats. “Just a special, special baseball player.”

By the end of the year, Votto led the league in extra-base hits.

Why is Joey Votto here? Not to be famous, he realized quickly. He joined the Reds as Ken Griffey Jr. was departing, and he knew early that he did not want the attention Griffey got. “Not because I can’t handle it,” Votto says. “More because he was so vibrant. Smile, home runs are entertaining, his grace on the field—just his personality in general matched more of a national style. Me, I don’t know if my style matches. You have to get to know me, I think. The people in Cincinnati have gotten to know me.” Indeed, fans recognize him regularly at home, and fairly often on the road, especially in the Midwest. But no one seems to take much note in Canada.

“Sometimes I get a little sad, because you want to make home proud, and I don’t really move the needle, so it can be a bit of a bummer,” he says, then pauses. “Not a bummer. It’s not because I want to be lauded. It’s more because I hope I make them proud.”

Kareem Elgazzar/The Enquirer/USA Today Network

Why is Joey Votto here? He hated the idea of explaining why he walked away in 2009. He keeps his personal life separate from his professional life. Even longtime Reds staffers can think of only one or two occasions on which they have met his mother, Wendy, who works as a sommelier, and he does not make her available for interviews. He has three younger brothers; one is an electrician, one works in a restaurant and the third just graduated from college to be a mechanical engineer. They, too, are off-limits to reporters. He says there is “not really” anyone else who has been around him for his whole career.

Still, he felt he had to tell fans why he became the rare major league player to go on the injured list due to stress. His father, Joseph, had died suddenly on Aug. 9, 2008 at 52. Votto took the week of bereavement leave the league offers, then threw himself back into work. The noise of the sport helped drown out the grief for a while, but by early the next season he was having panic attacks during games. He was hospitalized twice. In May he took nearly a month away from baseball, and he spoke publicly about why. He wanted other people to feel less alone. He became one of the first athletes to take mental health as seriously as physical health.

“I didn’t have a choice,” he says now. “I was not trying to blaze a trail.”

He had to go away, and he had to come back. He honors his first coach, Joseph, by sprinting to first base on pop-ups in spring training B games. Votto usually uses something new and catchy as his walk-up music (right now it’s Mac Miller’s “Nikes on My Feet”), but on the anniversary of his father’s death he asks the audio guys to play songs his dad loved: “Dream On” by Aerosmith, “Comfortably Numb” by Pink Floyd, “Cocaine” by Eric Clapton.

Once, early in his career, Votto went home for the offseason and raved about the clam chowder he had eaten on a road trip. Joseph, a chef, took to the kitchen and emerged with an even better version. “He wanted to have that connection with me,” Votto says now.

They shared more than a name. Votto admired his dad’s steadiness and the pride he took in what he did. Joseph was happiest when he was working, spending time with his family and taking occasional breaks to recharge. Votto feels the same way. He says he is an introvert who needs people. He does not have a family of his own, he says, “but maybe one day.”

In the meantime, he works with a Spanish tutor in the offseason. He recently finished his sophomore year as a geography major online at Florida. (He still has a ways to go before graduation. “It took me 17 years to get to junior,” he says. “It’s gonna be a bit.”) He takes improv and stand-up comedy classes at the Second City in Toronto. Initially he wanted to communicate better with his teammates and in interviews, but now he just enjoys it. His instructors have told him that nine out of 10 jokes will bomb, meaning Votto is pursuing the rare industry with a higher failure rate than hitting. Comedians develop what they call a “tight five,” a five-minute set of their best material, delivered with as few extraneous words as possible. Before the pandemic hit, Votto was planning to perform a tight two or three, he says. He declines to share his jokes, saying he hasn’t practiced in a while. His set stays away from baseball, he says. “Just embarrassing things about me,” he says.

He thinks often about what he wants to be when he grows up. He thinks he might like to be a chef.

Why is Joey Votto here? In 2016, Alex Shea, a 15-year-old baseball nut receiving chemotherapy at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for stage 4 Hodgkin’s lymphoma could barely believe it: His hero was poking his head into his room, asking if he could come in.

Votto lives a largely monastic existence. Each morning, he climbs out of bed and drops immediately to the floor for a series of mobility exercises. He plays chess online and listens to music (a lot of Frank Ocean) while he waits to report to the park. He cooks himself basic, healthy meals. He reads The New York Times—although he reads hard news only on off-days. Once Opening Day comes, he does not drink caffeine or stay out late or see friends. His social calendar is limited to daily games of chess in the clubhouse, usually with outfielder Aristides Aquino. "I've beaten him three times," Aquino says proudly.

During spring training 2019, he went to dinner with bench coach Freddie Benavides, Pickler and their wives. “This is nice,” Votto said that night. “We probably won’t do it at all during the season.” They did not.

Votto thinks often about the inherent selfishness of his job. It can be easy to forget there is a world out there. “The best way I’ve counteracted that is by giving,” he says.

Courtesy of Brian Shea

When he won his Gold Glove, in 2011, he called Benavides, then the Reds’ player development field coordinator who had tutored him at first base. Votto flew Benavides and his family to New York for the awards ceremony. When the coach got home, there was a box at his door: Votto had Rawlings produce a replica of the trophy and mail it to him.

Whenever Votto breaks a record, the fight for his gear begins: The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum wants it, as does the Reds Hall of Fame, as does Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. They make a list and divvy it up. Votto’s only request is that some pieces be auctioned off to benefit the Reds Community Fund.

Votto is the Reds’ nominee for the Roberto Clemente Award, the league’s highest humanitarian honor. He admires Clemente but says he does not particularly care about the title; he prefers to work in private. In May he arrived at the Reds Hall of Fame in full uniform to present the museum with home plate from the game in which he hit his 300th home run. He clattered around on his spikes for a while before cutting the visit short; he was due 10 miles north to play baseball with the kids at the Reds Youth Academy.

The team often learns after the fact that Votto has called Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and asked to stop by. On one visit, he met Alex Shea, the 5' 5" baseball nut. They spent 45 minutes together discussing Alex’s high school team and Votto’s batting stance and the difference between ash and maple bats. Votto signed a baseball for Alex’s younger brother, Brady, who was at school: “Sorry I missed you. Next time!” He meant it: He came back later and asked for Alex again, but the boy had already been discharged.

Five years later, Shea is a 6' 4" sophomore lefty at Cincinnati. He has a 95 mph fastball and is five years in remission. Before Saturday’s Reds game, he and his family reintroduced themselves to Votto. He meets a lot of kids; no one expected him to remember this encounter. But he beamed when he saw them. “Wow,” he said. “You’ve gotten a lot taller!”

Why is Joey Votto here? He can’t quite summon the rudeness to blow off a reporter who is standing in front of him with a follow-up question, so he lingers by the bat rack at Great American Ball Park to consider the answer.

He said earlier that this is all he does. Why is that?

Votto furrows his brow. “I don’t know what you mean,” he says.

Why is this all he does in life? Why doesn’t he make room for anything else?

“That’s what it asks of you,” he says. “To perform at a level that I would view as satisfying, it requires full-time effort.”

Bill Streicher/USA TODAY Sports

Why is Joey Votto here? On Sunday evening after a home game, anyone looking for the most important Reds player since Griffey should not head to the batting cage or the players’ lounge. No, you will find him hunched over his teammates’ cleats, wearing a white REDS CLUBHOUSE shirt with his name over the right breast, shining shoes. The clubhouse staff bestowed the uniform upon him on the occasion of his 10th season on the Reds’ major league roster, and he repays them with half an hour or so of work once a week.

“He’s pretty good,” says Rick Stowe, the Reds’ senior director of clubhouse operations. “He could fill in.”

Votto places the shirt alongside his MVP award as his most prized baseball possessions. They represent his twin passions: being great and grinding.

His dad taught him about both. He also taught him about longevity. When Joseph was in his early 40s and Joey was a teenager, they played catch and pickup soccer. “I feel great,” Joseph would tell his son. “You can play into your 40s.” They made a “pact,” Votto says now, adding that he signed that long-term deal in large part because it would take him past his 40th birthday.

Votto is renowned for his consistency. But if he had kept doing what he’d always done, he would not have been able to keep his promise. “My old version was trying to create a style of play that [meant] I could be in a conversation for best hitter in the game, and I was,” he says. “But it was exhausting. This one, I feel like I can just show up five minutes before the game and perform. It's really satisfying. That's kind of a s----- thing to say, but I mean it.”

Why is Joey Votto here? Because he wants to be.

More MLB Coverage:

• Will This Mariners Rebuild Be Any Different?

• The Ohtani Rules

• How MLB Squashed its Fake-Memorabilia Problem