One year after a 14-year-old basketball player was killed on a playground court, the pain of those closest to him remains raw.

Every morning last fall before school, Daja White waited for her friend Aamir Griffin at the bus stop on the corner of Foch and Guy R. Brewer Boulevards in the South Jamaica neighborhood of Queens. They boarded the Q111 and rode past a mural of a Buddhist monk holding a placard with red lettering: GET OUT WHILE YOU CAN.

When they reached Jamaica Avenue, they transferred to the Q30 and took it to Benjamin N. Cardozo High in Bayside, where they were freshmen, seven miles and an hourlong trek from home. Aamir had deep-set dimples and a broad grin; Daja’s wide smile showcased pink bands on her braces. He was 14; she was 15. Basketball was their bond.

Residents of the Baisley Park Houses knew the rhythm of the relationship: If a ball was bouncing, it was one of those two dribbling on the fenced-in asphalt beneath their windows. Aamir and Daja were readying to be Cardozo Judges, with Aamir set to suit up for the junior varsity team in coach Ron Naclerio’s storied program and Daja vying for a girls’ varsity spot. Aamir, who thrived behind the three-point line and called long-range shots his “signature layups,” worked on the timing of his hesitation dribble and flicked floaters to finish in the lane. Already wearing size-13 sneakers, he stood 5' 11" and had committed to better conditioning—strengthening his core with a medicine ball workout and building speed with timed sprints—to prepare for prep battles and pursue a college scholarship. At 5'6" and fearless after years of competing against four older brothers, Daja did it all, anticipating Aamir’s spin moves and knocking down step-back jumpers as she dreamt of a pro career abroad.

On weekends, the two friends visited Green Acres Mall in nearby Valley Stream, where Queens fades into Long Island, to shop, eat and escape local perils, including an escalating feud between two local gangs. But almost everything else revolved around a basketball court. That was the case on the evening of Oct. 18, 2019, inside Catherine and Count Basie Middle School 72’s gym in Queens. He was on the hardwood, playing in a fall league game; she was in the stands. Aamir’s team, Not in My League Tribe, trailed Team Bay Bay Kids by two points with two seconds left when he received an inbounds pass on the far side of half court.

Dressed in a black No. 2 jersey, Aamir, who had already drained four three-pointers, squared up. A defender sprinted toward him, extended a hand and leapt to contest the shot, but Aamir heaved the ball from midcourt just in time. The ball arced toward the ceiling before falling through the net. Daja recorded it all—buzzer beater and subsequent bedlam—on her phone’s camera.

“Let’s go! Let’s go! Let’s go!” she screamed as teammates swarmed Aamir.

The next morning, Aamir sent a private message on Instagram to Daon Merritt, the league’s organizer: My dad said he balled with you. … His name is tootie.

Oh, Merritt tapped back. That’s where you get your shot from.

Everyone in Southeast Queens knew the scorer who went by Tootie. Once feted for scoring 44 points in a game for Campus Magnet High, Warnell Wells ran afoul of the law in the decades since. His most recent incident: In 2018 he was charged with menacing with a firearm after a former girlfriend alleged she heard two gunshots outside a friend’s house around 1 a.m., looked outside and saw Tootie, alone, running away. Police recovered a bullet from a first-floor bathroom.

But now Tootie’s son was hellbent on making basketball his way out, promising family members he would buy them new cars and houses when he reached the NBA. Eight days after his game winner, around 7 p.m., Aamir and another friend, Kevon Clarke, returned to the basketball court inside the Baisley Park projects, where Daja was already hanging out. They had no ball, so they played a game of What if?

What if, they wondered, gunmen approached the court and opened fire? In a bullet-riddled corner of Queens where gangs congregate and police maintain a heavy presence, this was not an academic exercise. Aamir fell playfully, as if struck. Daja laughed and said she would flee to her apartment after running through the playground’s far gate. She told Aamir to get up. Enough kidding. He did—but then Daja heard what sounded like fireworks exploding behind her. Aamir fell again, and this time when Daja looked over she saw him convulsing by the three-point arc on the right wing.

Daja ran into her building, rode the elevator to the sixth floor and hurried to her living room window, which overlooked the court. She watched and sobbed as police tried first to resuscitate Aamir, then strapped him onto a stretcher, rolling him into an ambulance that sped away.

At 8:58 p.m., two minutes before his curfew, Aamir was declared dead.

Week after week, Aamir Warren Wells Griffin swirled into view on the ultrasound monitor at St. John’s Hospital. In grainy black-and-white images he progressed from a featureless sphere into a recognizable profile, and when he arrived on June 8, 2005, it was a natural birth. He weighed seven pounds and possessed a pair of round, winsome cheeks. His mother, Shanequa, doted on him, dressing him in all-denim outfits that were street chic, from his durag down to his Timberland booties.

“That baby stayed fly,” she says. “You can’t tell me my baby wasn’t the man.”

Aamir was her second child; the first, Armani, came when she was 17. Shanequa and Tootie grew up a few blocks from each other in the Cambria Heights part of Queens, three miles east of South Jamaica, and both knew the heavy toll of gun violence. On a January morning in 1993, Tootie’s own father, a ticket collector for Amtrak, had dropped off 11-year-old Tootie at his mother’s place following a father-son weekend when he was shot and killed with bullets to the head and body. Tootie did not go to school for two weeks, and he never spoke to a counselor. But he took up basketball after his father’s death, and it became his release by the time he attended Campus Magnet. At 6' 3", Tootie was a get-the-ball-and-go guard for Chuck Granby, the first public school coach in the city to collect 700 wins. In Tootie, Granby believed he had a talent capable of playing Division I ball, and he gave the boy a green light. Tootie relished the free rein, scoring 16 of the Bulldogs’ 30 points in one hot streak and balancing 39 points with 10 assists in another.

It was against Cardozo High that someone finally got under his skin. Tootie and Naclerio, the irascible coach in blue polyester pants, exchanged words throughout one game. When they reached a boiling point, Naclerio chided, “You think you’re going to college? The only college that would offer you a scholarship is URI.”

Tootie said he wasn’t going to “no weak-ass Rhode Island.”

“University of Rikers Island,” Naclerio shot back, referencing the infamous New York City jail. “And you’re dumb enough to take it.”

Tootie threw the ball at Naclerio. A technical was assessed and the guard, who already had four fouls, was ejected. The next year the school expelled him for what he says was retaliation against someone “putting hands'' on him. Thereon, he briefly attended a prep school in Pennsylvania and spent time at a junior college in Florida before falling off scouts’ radars. Back in New York, fatherhood offered him a chance for grounding. Tootie and his family hopped around Brooklyn and Queens before landing in public housing in Queensbridge, Red Hook and, finally, South Jamaica, close to Shanequa’s mother. After a year and a half, Tootie, who has two other children, moved out.

Aamir lived with his mother, sister, stepfather and a Yorkshire terrier named Madison on the fourth floor of building No. 4 in the Baisley Park Houses, three floors above a community center that was shuttered due to budget cuts in 2008. He played Call of Duty, relished pans of his mom’s soul food and listened to Pop Smoke’s “Welcome to the Party” on loop. He enjoyed summers with his grandmother—Tootie’s mom, Kim Walston—on Frog Hopper Lane in Charlotte, where the boy was known as Prince Charming and where he taught himself to swim when he was five. “He was determined like a shark in the water,” says Walston.

During the school year, Aamir called his grandmother every night on FaceTime, telling her about his academic accolades, from student of the month honors in his Korean class to his completing a young engineers’ program. To Herman Turner, an academic coordinator with the Southern Queens Park Association’s Beacon Program, a community center based in South Jamaica, Aamir was “an intelligent class clown.” A practiced mimic, he impersonated teachers when they left the room, but otherwise he was respectful.

When Aamir was in eighth grade he eschewed the cafeteria during lunch twice per week; instead he was often the first student to report to the second-floor classroom where Kevin Livingston led 100 Suits Academy. Livingston, 42, started the initiative in 2016 after two boys at separate Jamaica public schools brought loaded weapons into class. He saw a leadership void amid the neighborhood's gun violence and started mentoring kids twice per week. Eventually Aamir arrived, busting the teacher’s chops about his oversize suits—but he was also inquisitive when it came to the lessons about entrepreneurship, financial literacy, self-respect and HIV. Livingston’s approach fit Aamir, who once wrote to his mentor: “I like this program because I can express myself to boys that’s in the same predicament or witness the same things as me.”

The summer before high school, Aamir, newly emboldened, ran into Naclerio—a man who by then had 816 wins, the most in PSAL history, and whose alumni roster included former NBA players Rafer Alston and Royal Ivey—and tapped the coach’s shoulder. Aamir had enrolled at Cardozo, he said. But first his father wanted a word.

“He can’t be your son,” Naclerio would later joke to Tootie over FaceTime. “He seems like a great kid, and he’s good looking!”

The Baisley Park Houses, a complex of five eight-story red-brick buildings divided by Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, stand three miles north of John F. Kennedy Airport’s runways and far beyond gentrification’s waves. Built for low-income residents in 1961, the development housed a notorious round-the-clock crack operation, replete with lookouts on rooftops and $200,000 in daily street-level transactions, for much of the ’80s. Sales from that crew, overseen by famed drug lord Kenneth McGriff, helped sponsor basketball tournaments where whistleblowing was discouraged and where dealers wagered $50,000 or more on after-dark games. One night in the summer of ’88, one of McGriff’s associates struck a referee after a foul call, sending the official’s head crashing into the asphalt. He lost consciousness and died six days later.

Calm returned eventually, but in the summer of 1995, the Peace Tournament, another basketball spectacle held in the same park, was interrupted when gunmen opened fire. Bullets killed two bystanders; six others were hit. A woman was trampled amid the rush to escape.

Though the neighborhood is less violent today, teenage trigger-pullers still face off on social media and street corners in multiple precincts. Two rival gangs are among those culpable: Money World, on the Rochdale Village side of Jamaica, and the Trap Stars, by the neighboring Baisley Park Houses. The New York Police Department estimates that since January 2019 the warring factions are responsible for between 20 and 30 violent acts. The trouble has persisted despite the department’s surveillance efforts, which include a watchtower near Aamir’s bus stop, a camera monitoring the basketball court and steady foot patrols.

Police say it was a long shot that felled Aamir. The gunman fired multiple times from the corner of Foch Boulevard and Long Street, and three .380 discharged shell casings were retrieved from the scene. The bullet that killed Aamir spiraled 75 to 100 yards across a parking lot and slipped through a chain-link fence before burrowing in his upper torso. Police believe the shots were fired to scare or send a message to members of the Trap Stars, and that Aamir was an unintended target.

When a friend banged on her door to tell her Aamir had been shot, his mother rushed down the stairs before falling and breaking her left foot. Shanequa limped through the grieving process, embracing friends past midnight in rain and wind. In the week after the shooting, no eyewitnesses came forward, but mourners congregated on the court. More than 300 candles were arranged in the shape of a heart and lit each night on the patch of blue-gray asphalt. At the center of the display was a message to Aamir, scrawled on a basketball: you aint deserve this!!!

Tootie was in North Carolina, where Aamir used to spend summers, when his son was shot. He hopped in his mother’s red Prius with her and his girlfriend and drove 686 miles through the night. For days, he sat on a black milk crate at the scene as friends drained bottles of Don Julio and drew from cigarettes.

“[Aamir] was me without all the attitude and bulls---,” says Tootie, eyeing a photograph of his son. He remembers how his own father’s death shook him, how “my whole life has never been the same. The pain never leaves. But this one takes the cake. Life is f------ crazy. I wish I was with them. I don’t want to be with anybody else.”

On the morning of Aamir’s funeral, early that November, police halted traffic on Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, and a white horse pulled the boy’s black casket in a white carriage through the streets surrounding the housing project. Denizens observed from their windows.

When his casket was opened inside the Greater Allen A.M.E. Cathedral of New York, Aamir was dressed in a replica of Kyrie Irving’s Brooklyn Nets uniform, and his hand cradled a basketball. His coach eulogized him. “Aamir Griffin in the wrong place at the wrong time? Bull crap,” Naclerio said. “A 14-year-old kid doing what he loved, minding his own business in any park, should never be wrong place, wrong time.” At Greenfield Cemetery, mourners wept as Aamir’s casket was lowered into the same plot as his grandfather, whose own homicide case remains open after a quarter-century.

Two days later, in Queens Criminal Court, Tootie pleaded guilty to the charge of criminal contempt in the second degree that stemmed from his 2018 incident. Judge Deborah Stevens Modica addressed him from the bench.

“Mr. Wells, I understand you had a loss and I’m very sorry to hear,” she said. “I hope you’re going to be O.K.”

When a bailiff informed Tootie he had to provide a DNA sample in an anteroom, he replied, “I can’t stop shaking.”

Tootie steadied himself enough to play in a memorial game at Aamir’s middle school two weeks later. It was a Friday night, and afterward the crowd walked over to the schoolyard, where 100 balloons were released into the sky.

“Yo!” a teen shouted as police encouraged them to depart. “It’s about to get hot.”

The crowd thinned, but one group would not disperse. Officers in a white SUV rolled slowly behind them. “Time to go home,” an officer announced.

This was 8:37 p.m. An hour later, Talasia Cuffie, a cousin of Aamir’s who had attended his memorial, was stabbed to death a block north of the Baisley Park complex.

Sitting in her apartment the next week, Shanequa shook her head. “Too much is going on in my family,” she said, her voice rising. “Too much death.”

Rodney Harrison, the NYPD’s chief of detectives, passes framed portraits of predecessors when he reports to his office each day on the 13th floor at One Police Plaza. As the first Black person to serve in the post, Harrison, 51, saw his reflection when he received the basic description of Aamir the night of the murder—14 years old, Black, Baisley Park Houses resident.

Harrison, who himself had lived a mile down the road in Rochdale Village—a 20-building complex constructed in the 1960s on the site of the old Jamaica racetrack—well into his 20s, soon learned that Aamir had attended Cardozo, where he too had commuted by bus to play for Naclerio in the 1980s. “Spooky,” he says.

Two days after the shooting, Harrison sat with Shanequa and promised to catch the perpetrators. He attended the funeral, and he listened as Mayor Bill de Blasio announced at a community town hall that the Baisley Park Community Center, which sits on the first floor of Aamir’s building and remained closed during his four years there, would be reopened and renamed after the boy. de Blasio decried the continued closure of the center “in a community that is hurting right now,” though Aamir’s friends noted that he had been happiest outdoors. Collectively, they considered the basketball court their safe haven.

But law enforcement struggled to find cooperative witnesses or conclusive video evidence, and then COVID-19 coursed through the community, claiming more than 200 lives in Aamir’s predominantly Black zip code. To prevent gatherings, the city removed rims from playgrounds, and the court where Aamir was killed was locked until June 8, when he would have turned 15. That afternoon, the NYPD and New York City Housing Authority opened the court for a few hours, a nod to Aamir’s memory. Community affairs officers provided single-use masks at the gate.

On a rainy afternoon a month later, more than 40 officers returned for another ceremony. Standing on a walkway adjacent to the court, they prayed, sang a Gospel hymn and marched in a drum line during the dedication of a memorial bench outside Aamir’s building. One detective gifted the family a painting of the young baller in action, and Melinda Katz, the Queens District Attorney, railed against the local market for illegal guns. Meanwhile, Tootie, back from Charlotte, stood away from the crowd before announcing himself as the father and shouting epithets in the direction of police. “Stop shooting Black people!” one of his friends yelled.

Harrison heard the commotion, but he trained his attention on troublesome statistics: 71 shootings in the previous week, resulting in 101 gunshot victims. Fewer than 48 hours later, a one-year-old boy in Brooklyn would be shot and killed in his stroller near a playground. During a summer of unrest, amid the pandemic and deepening distrust in law enforcement following the police killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, the city experienced a surge in gun violence not seen in 14 years.

Growing up, Harrison hadn’t cared for cops and witnessed what he considered to be law enforcement’s harassment of neighbors during the crack epidemic, but he found the cycle of violence and silent witnesses that kept homicides unsolved “extremely frustrating.” His old neighborhood is safer these days: During Harrison’s teenage years, there were at least 40 homicides annually in the 113th precinct, compared with just 15 in 2019 and even fewer this year despite the citywide jump. But after helping create and deploy neighborhood policing strategies when he was chief of patrol, Harristill recognizes the need to build trust between police and communities.

“People are extremely intimidated to point out a shooter who committed a homicide,” Harrison says. “They don’t want to deal with any potential retaliation.”

For Aamir’s family, closure remains elusive. The night of his death, security cameras captured two young men—police believe they were teenagers—dashing south on Long Street, toward a neighborhood where members of the Money World gang are known to congregate. Each appeared to be holding something, and one of them looked over his shoulder without breaking stride.

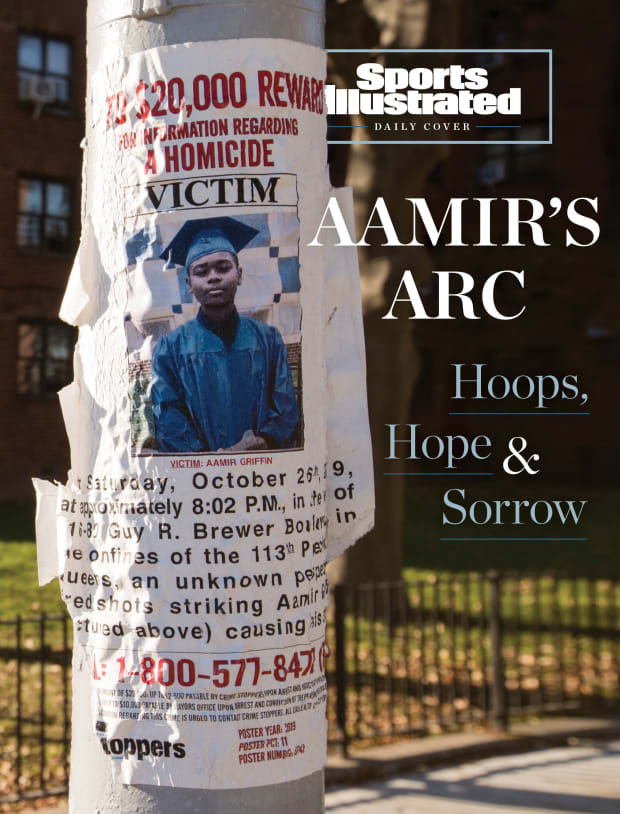

While one 21-year-old suspect was arrested four days after Aamir’s cousin Cuffie was killed, charged with luring her to her death, no one has been charged with her homicide. And while three suspects have been identified in Aamir’s case, no arrests have been made. Nine months into the investigation, Harrison doubled the reward, to $20,000.

“A lot more work has to be done,” he says.

Russet leaves rest inside glass candles that once burned in Aamir’s memory on the Baisley Park basketball court. Reward posters featuring the teenager in his blue middle-school graduation cap and gown remain—barely—on lampposts, so weathered from the New York summer that the word VICTIM, in bold type, is in some cases obscured, no longer readable. More than a year after Aamir’s killing, Daja keeps her dribble alive on a clear November afternoon as she eyes a mural of her grinning friend, splashed across a backboard.

“There was something different about him,” she says. “He treated you like a girl, like a lady.”

Daja couldn’t sleep the night Aamir was killed, and at 3 a.m. she departed for a cousin’s place outside the project. She didn’t go to school for a week, and when she returned she spoke with a counselor a few times. But she chose not to play basketball for Cardozo—she stopped playing altogether for a while—and today when she walks by places where she and Aamir shared memories, she flashes back to that night in October 2019. On multiple occasions, those flashbacks exacerbated her preexisting anxiety, and she once called 911 when she felt a shortness of breath. Last summer she transferred from Cardozo to Francis Lewis High, but because of COVID-19 she has yet to set foot inside her new school.

She often replays the night of Aamir’s death, recalling their game of What if? “Sometimes I think it’s my fault,” she says. “If I didn’t tell him to get up, then it probably wouldn’t have happened.”

Reminders of Aamir surround Daja, who has lived in Baisley her whole life. On this November day, she is the lone girl playing with nine boys in a full-court game. Among them: Kevon Clarke, the other boy who was there when Aamir was killed; and Aamir’s cousin Le’Quan Taylor, the first person Daja called that night.

Aamir’s mother looks on from the sideline. Now 38, Shanequa, who was recently promoted to a supervisor at the veterans shelter where she works, became a grandmother in May. As she watches her daughter, Armani, push little Elias in a stroller by the court, she notes that police recently installed a camera on the lamppost where the fatal shot was fired.

“I still don’t know how my baby felt when he was shot,” she says. “I think about him every day—there’s nothing I can do. I wonder what he would look like playing with his friends.”

Daja dribbles up the right side of the court, past the milk crate where Tootie mourned his son. She had seen Aamir’s father come and go, but he stayed away of late. Tootie, who has taken to going on long drives to find a sense of calm, recently visited the cemetery where they buried his father, and then his son. After months of delay, a granite marker—engraved with a No. 2 jersey, a rim and a basketball—had been laid atop Aamir’s burial plot.

Daja visited once, but she also maintains her own memorial. Each night, before falling asleep, she lies next to an orange wall dotted with photos of Aamir and a letter she wrote following his death: I love you Aamir. I hope you balling in peace right now. Then she prays.

“Protect me.”