For fans of a league where player movement is on the rise, buying NBA jerseys is more challenging than ever.

There have been times throughout the years when parts of Rockets fan Allison Wollam’s walk-in closet look like an unofficial tribute to the Houston basketball heroes who’ve fallen by the wayside.

A 46-year-old diehard who fell in love with her hometown team during the club’s back-to-back title run in the mid-1990s, Wollam made a point to start collecting jerseys in the early 2000s. She amassed several during that era, including stars such as Yao Ming and Steve Francis, as well as local fan favorites such as Cuttino Mobley and Luis Scola.

Then, when the club rebuilt itself around superstar James Harden, Wollam’s closet collection grew sizably. There were “a gazillion” Harden jerseys in seemingly every color. But there was also a Pat Beverley jersey. A Clint Capela one. A Chris Paul. A Russell Westbrook one, too. Wollam even bought the Rockets jerseys of Carmelo Anthony and DeMarcus Cousins—a pair of ex-stars who were dumped separately by Houston after 10 and 25 games, respectively, after failing to jell on the court.

She’s since donated the vast majority of her collection, leaving just women’s sleeved Beverley, Capela, Westbrook and Harden jerseys hanging in the closet following the cathartic purge. “[The Cousins jersey purchase] was my last one, where I said, ‘I’m stopping—this is it.’ I learned my lesson with that one,” says Wollam, citing the $70 price tag for the barely used Cousins jersey. “After a while, it’s just sad. [My closet] is like this burial ground for guys who used to be on the Rockets.”

Chris Schwegler/NBAE/Getty Images

With so much turnover in Houston—the Rockets have fielded 84 different players over the past four-plus seasons, the NBA’s most in that span, according to Radar360—it would be hard to blame fans such as Wollam for closing their wallets from a jersey-buying standpoint. The revolving door makes it uncomfortable for some to make the financial investment, one that used to feel far less risky.

It’s an issue that’s bothered more than just Rockets fans lately, though Houston’s arguably had more instances of that nature than just about anyone, given the if-you-blink-you’ll-miss-it tenures of John Wall, Anthony and Cousins. More broadly, Kemba Walker’s days as a Knick are already over just months after the Bronx native signed with his hometown team. Westbrook, after 11 years with the Thunder, has been with three different teams in the past three seasons. An ill-fitting Al Horford, who’d signed a four-year, $109 million contract in 2019, lasted just one season in Philly before being sent to Oklahoma City. Following the high-profile trade in which he was swapped for Cleveland’s Kyrie Irving in ’17, diminutive guard Isaiah Thomas played all of 15 games for the Cavaliers before getting dealt to the Lakers. Jimmy Butler played less than one regular season’s worth of games, total, for the Timberwolves before making it known he wanted out of Minnesota. He then got traded to Philadelphia, where he’d stay less than one full season before joining the Heat. And of course it was nearly a decade ago, with then superstar Dwight Howard, that we saw the big man move on from the Lakers after just one season—and the massive trade from the Magic—to go to Houston, a decision that felt stunning at the time, but now with hindsight looks like it was merely a sign of things to come.

David Berding/USA TODAY Sports

If player movement seems more brisk than before, that’s because it is. The percentage of players who find themselves on a different team from one year to the next has been consistently climbing for decades now. Throughout the 1980s, just 16.8% of players moved from one locker room to another after a season ended, according to data from Stats Perform. That number jumped to 22% during the ’90s and 23% during the 2000s. And during the most recently completed decade, from ’10 to ’20, the NBA hit an all-time high with almost 27% of players landing with new teams the following year.

Paring numbers down to look solely at top scorers, the narrative is much the same. Players who finished in the top three in scoring on their teams landed with new clubs the next year 20.6% of the time between 2010 and ’20—the highest rate ever of player movement among top scorers, per Stats.

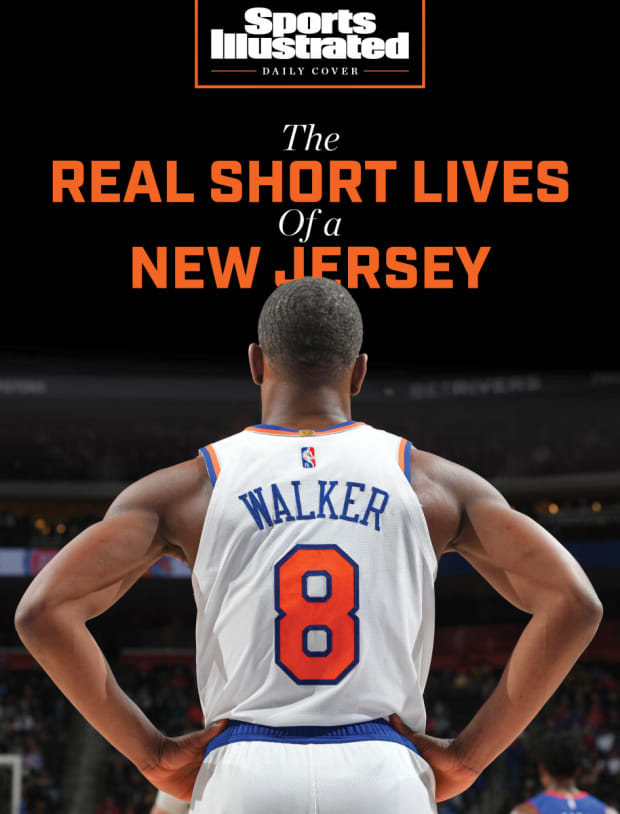

We’re beginning to see more instances where NBA teams almost instantly seek to wash their hands of a signing or trade that isn’t working out. Walker, who at the beginning of November had been the Knicks’ featured player in a stirring jersey sales campaign, was pulled from the rotation just four weeks later. (Coach Tom Thibodeau ended up going back to Walker after injuries and COVID-19 left New York with few alternatives. But the team’s since shelved the four-time All-Star for the remainder of the year.)

“Right when the Knicks got Kemba, I got the jersey thinking, ‘This is an awesome story—it’ll be cool,’” says Scott Walls, a 29-year-old Knicks fan and Westchester, N.Y., native. “But the next thing you know, he’s not even playing. And it’s like, Do I even want to wear this now?”

Walls and several other Knicks fans who’ve made the plunge for a Walker jersey say they can live with it, given Walker’s upstanding reputation in the sport and his undying pride as a New York City legend. But his jersey is far from the first one to be devalued shortly after being marketed to the masses.

Hell, even Walls himself has felt this pain before. Like scores of fans, he bought a Jeremy Lin jersey toward the end of the point guard’s magical, out-of-nowhere run in 2012, but then watched the Knicks decide against signing him back that summer after Houston made him a poison-pill contract offer as a restricted free agent. And more recently, in January ’19, Walls purchased a Kristaps Porziņģis jersey T-shirt, which then became obsolete once he got traded to the Mavericks two weeks later.

“With that one, I remember saying to myself, ‘Well, at least I only got the $30 shirt, instead of the $120 jersey,’” says Walls, who has invested in a handful of RJ Barrett jerseys, but has otherwise—with Immanuel Quickley and Mitchell Robinson—stuck to the jersey shirts, fearing the Knicks will then turn around and trade the player away. It’s obviously a founded concern: In an almost unthinkable statistic, New York hasn’t re-signed one of its first-round picks on a multiyear deal since 1999, when point guard Charlie Ward from those consistent, rough-and-tumble 1990s Knicks clubs, was retained.

While it’s challenging to place just how en vogue NBA jerseys are in today’s culture, it wasn’t long ago—during the early 2000s—that they were all the rage within America’s pop culture. In that era, things shifted from merely teenagers or kids being able to wear them. You seemingly couldn’t watch a high-profile rap video without seeing one. And it was around that same time that sports-apparel company Mitchell and Ness struck a licensing agreement with the NBA for the right to manufacture throwback jerseys, which exploded on the market and further popularized the growing brand. To this day, there’s arguably no quicker way to identify a fan than by seeing one who’s dressed in a jersey.

If player turnover has made some fans more reluctant to buy jerseys, it hasn’t shown in the league’s internal data in recent years. In fact, league officials say jersey purchases have jumped by double-digit percentages in five of the past six years—a boost aided in part by Nike and the NBA rolling out dozens of new styles and specialty jerseys, which encourage new sales. Jersey purchases continue to account for about 40% of the league’s apparel sales, a number that’s in line with historical norms, officials say.

Some recourse exists for fans who get burned by the quick-churn nature of today’s player turnover. American Express offers to replace fans’ jerseys for free if a player switches teams within 90 days of the person’s purchase, and the company extends that deal out for a full year when the purchase is made using an American Express card. (It’s not clear that this helps non-AmEx holders who bought Walker jerseys at the start of the season. Since he’s still technically on the roster, there’d be no grounds to exchange the jersey. And fans who bought Wall’s jersey would be in a similar boat, despite him being held out.) Going that route is perhaps the best way for a fan to guard against a team or executive that swaps out players like a fantasy football player.

There are other approaches that can be taken. Ethan Giles—a 27-year-old Sixers supporter who owns a stable of obsolete jerseys including Horford, Seth Curry, Josh Richardson and Robert Covington—says he orders his from China for $40 to avoid feeling let down when players inevitably leave town. (With 78 different players since 2017, Philadelphia isn’t far behind Houston in terms of player movement.) And while authentic throwback jerseys are a small fortune relatively speaking, because they represent iconic players from a prior era, at least there’s no risk of them being moved at the trade deadline.

“If I’m gonna buy a jersey, it’d be a throwback at this point,” says 35-year-old Jammel Cutler, adding that both his career as a writer covering the NBA and his hard-knock life as a Knicks fan during the 2000s diminished his desire to buy current players’ jerseys. Cutler said he watched Latrell Sprewell, Trevor Ariza, Steve Francis, Raymond Felton and Landry Fields get traded—and Allan Houston retire—shortly after spending well more than $100 on each of their New York jerseys.

Chris Szagola/AP

Still, for how cutthroat a handful of teams have gotten in some instances, there’s no question that player empowerment has been a factor in the high level of churn, too. The trade that sent Thomas to Cleveland in exchange for Irving, for example, almost had to include a player of Thomas’s caliber, as the Cavs were concerned that LeBron James—who was a soon-to-be free agent—would skip town without an All-Star-caliber replacement to keep the team in title contention. And just last month, with speculation swirling, Harden asked out of Brooklyn, even though he’d just pushed for a trade to get out of Houston the season before. It all resulted in the one-time MVP being dealt to the Sixers.

While the trade ignited a legion of Philadelphia fans, and likely prompted brisk jersey sales business at the team shop, it forced some of Harden’s previous fans to pause. That was even the case with Wollam, the Rockets fan who owned several Harden jerseys and continued to support the guard from afar.

“I was happy for him when he left because the ownership here was never going to pay [for a contender], and a lot of the time he was here with a bunch of scrubs, or his best teammates would get hurt,” says Wollam, who bought a Harden Nets jersey, and whose parents got her Nets pajamas for Christmas. “But the Nets situation—the way he turns it off, then back on—was a bit of a turnoff. It wasn’t a good look. I still support him, but I feel like I bought into Brooklyn more than he did.”

Wollam even bought tickets to an April Nets game at Barclays Center as a college-graduation gift for her nephew, who’s a Kevin Durant fan. She’d planned to bring her Harden jersey on that trip, to root for her favorite player. But then the trade happened. Now, she says, “I probably can’t wear it to that game anymore.”

More SI Daily Covers:

• Behind Ja Morant’s Sudden Ascent to NBA Superstardom

• Can Overtime Disrupt Basketball With … Twins?

• Nikola Jokic Gets Lost Among the Stars. And He's O.K. With That.