It took creativity, sketchy Wi-Fi and tireless student managers to bring Brad Dal Bon to his new team, 3,000 miles away, without ever leaving his house.

As summer ended, on a home field tucked in the shadow of the Kenai Mountains where the Kachemak Bay spills into the Gulf of Alaska, the Mariners of Homer High School returned to football practice.

Coach Justin Zank, eager to start his second season, rolled into workouts with a pair of donated iPads and a Bluetooth speaker the size of a submarine sandwich. He showed them off to his quarterback and team manager, who both asked what they were for. “You’ll see,” he told them. Rumor had it, the Mariners were even getting Wi-Fi installed in the press box.

Zank got this job after reviving a football program over eight years in the nearby village of Voznesenka, 25 miles north of Homer. He was used to taking big swings in life, like 10 years ago when, at 27, he and his wife decided to sell all their possessions and leave their home in southern Florida for subzero winters and remote gravel access roads 5,000 miles away. They had never been to Alaska and did not have jobs lined up. So if anyone was going to buy into this plan with the iPads, it was him.

Zank had spent the early parts of the COVID-19 pandemic talking on the phone with Brad Dal Bon, a teacher and retired football coach at a high school in Grass Valley, Calif., whom he’d met through a friend. Dal Bon had coached for more than 25 years and had a lot to offer the program. Zank had never met him in person—they’re separated by a 60-plus hour drive through the Yukon Territory, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and some of California—but it was Dal Bon’s suggestion that would alter the course of their season and expanded what coaches around the country thought was possible while locked down amid a generational pandemic. He told Zank he should hire him.

Dal Bon had a dream of a quarantine adventure coaching high school football in Alaska. He had spent time in the 49th state, for some football camps and Dramamine-fueled charter fishing in the early 2000s—he relished catching everyone else’s trout and salmon limit while his friends vomited off the side of the boat. Schools and sports were more open in Alaska during the pandemic, less affected by the virus coursing its way through the lower 48 states. Dal Bon was willing to pack up for the fall, leave his family for a few months and find an apartment in Homer, teaching his California high school students over the internet if the novel coronavirus continued to shutter his district’s doors. But as he and Zank discussed the arrangement, Dal Bon became unsure whether California would buckle and reopen at some point during the semester, requiring him to remain in state. He pitched Zank on a different arrangement.

“He told me the idea was way out there,” Zank says. “I didn’t think so. I thought it was an innovative way to get good coaching on my staff. I was all for it right off the rip.”

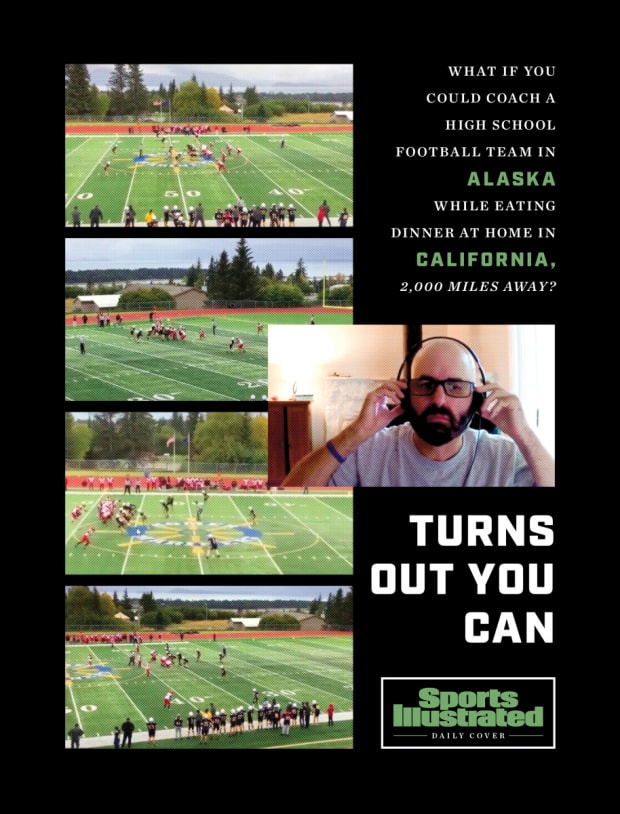

So began the kind of fever dream we all conjured up at some point while quarantined during the pandemic. What if we could use this time to do something truly strange and bold? What if we flipped the modern banalities of constant web conference calls into something that satisfied a hunger inside of us? What if you could coach a football team every day in Alaska without leaving your home in California, softly scolding your kids for turning up the volume on the TV so loud that you couldn’t hear the defensive call made at a practice? What if there was an eager student manager on the other end of a spartan internet connection willing to be your avatar for the year?

Welcome to the story of Zank, Dal Bon and the upstart Homer Mariners. Capping a year of virtual happy hours, virtual masses, virtual funerals, virtual birthday parties and virtual road races, they may have unintentionally presented the nation with its first Zoom football team. And they finished the season as conference champions.

“Someone could carry an iPad around and be me,” Dal Bon says, making one of the more Orwellian virtual learning pitches in recent memory. “Or I could be them. Or whatever.”

* * *

Dal Bon is 48 years old, bald with a tightly groomed beard. He wears rectangular, dark-rimmed glasses that, when combined with the black headphone and speaker set he uses for online coaching, give him the appearance of an energetic telemarketer or, perhaps, the kind of person who plays Call of Duty professionally. He is married with two kids.

When Zank called him over the summer and said he’d acquired iPads, Dal Bon warned him that he did not want to just consult for a football team—which is a standard industry practice—that he would not simply watch film and provide notes. He wanted to be involved in the game-planning process and he wanted to be connected on game days. He wanted a position to coach, and there was an opening at the outside linebacker spot on Zank’s staff.

That’s how Dal Bon ended up in a team meeting after that initial workout, introduced as one of the team’s two new coaches. (The other, John Jessen, was a friend of Dal Bon’s who had actually moved to Alaska, 2 ½ hours from Homer, and would coach in person on game days and virtually on days when he could not make the drive to practice.) The immediate reaction varies depending on who you ask.

Carter Tennison, the team’s starting quarterback and an outside linebacker: “I guess you could say I was interested and intrigued as to why we had some guy I don’t know talking to me over an iPad.”

Zank: “I think my other assistants thought I was full of it. When I introduced coach Dal Bon to everyone on the iPad, everyone just laughed. I don’t know if they thought it was serious or not until we got it going.”

Dal Bon: “The kids were definitely like,’ What is this weird thing going on with the team manager carrying around an iPad?’ So then I was like, plug the speaker in, I want to coach.”

Hailee Alexander, a senior team manager: “It was definitely a shock. I was like, how are we supposed to do this?”

Alexander was the one tasked with carrying Dal Bon around the field. In 2019, her duties as the team manager began and ended with the creation of a “clean music” practice playlist. This season, she found herself in on every play. Her plan during a typical practice was to stand near the safety with the iPad providing a panorama of the defensive formation and “try not to get hit by the ball” while giving Dal Bon a complete look at what’s happening on the field.

It was a process of trial and error. Alexander was backpedaled into multiple times. The day before speaking to a reporter, she was nearly run into by two different coaches. Most of her days were spent trying to keep an internet connection while tending to Dal Bon’s frenetic whims—he’ll want to be in a million different places at once. She had to learn the defense’s calls to properly relay them to Dal Bon, who often couldn’t hear the other coaches from his laptop at home.

While the Wi-Fi was being set up, Alexander would use her personal cellphone data or Zank’s personal cellphone data to create a wireless hotspot from which to run the iPad. On cloudy days it could seem almost hopeless to achieve any type of connection at all. Alexander had a hard time explaining the potential alterations in the family cellphone bill to her grandparents.

“They were like, why is there a coach on the camera?” she says. “They thought it was a little crazy because they’re still learning how to use their phones.”

But it didn’t stop Dal Bon from quickly becoming part of the family. After completing all of the state certifications required for a high school volunteer—he insisted on logging into Homer’s online volunteer portal the day it opened on July 1, submitting to a background check and filling out the required paperwork to formally register—Dal Bon would start meeting with players, specifically Tennison, on private Monday-after-game Zoom calls to add more instruction and break down film. He helped weigh in on different processes and offered suggestions to the young coaching staff about different call usages and how to align the defense. Zank eventually FedEx’d Dal Bon all the Mariners gear he impulsively ordered online, including a heavy jacket that will rarely be of use in California.

He developed nicknames for certain players, like a Russian safety he calls KGB, and had a running bit with both Alexander and the other team manager, Harmony Davidson, about the fact that he is an hour ahead and, thus, was able to eat dinner while he was technically at practice. Dal Bon would chew loudly into the iPad speaker, taunting anyone around who had to slog through the remainder of practice before getting their food.

“I’m like, ‘You guys hungry? Man, I’m eating a chicken salad and it’s awesome,’ and she’s like, ‘Well, we’re getting pizza later,’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, that’s later. I’m eating right now. Aren’t you hungry?’ ”

One of the strangest parts was how it all became so normal, how Dal Bon and Jessen, when he was coaching virtually, could appear like part of the staff even though they were often staring at the kids through a spotty internet connection. They discovered something that seemed to be universally true for all of us during a time of quarantine, whether it be a virtual coach, grandparent, teacher or friend. At some point they manage to transcend the screen. At some point, they made us laugh and love and, maybe in the case of Dal Bon from time to time, pull our hair out just as they would if they were there in real life.

“Both of those guys like to talk, and you can crank that Bluetooth speaker,” Zank says. “So when they’re both talking at the same time that I’m running offensive practice or doing whole team drills or calling plays, those two guys will be chit-chatting one another on a Zoom call over the Bluetooth speaker and the manager will be standing right next to me. So that drives me up the wall sometimes. I gotta tell them to shut up and to get that iPad out of my face.”

Dal Bon joked that the cool factor of what they were trying to accomplish wore away after about a week or two (especially for the overtaxed managers), yet everybody held their grievances in check.

“We’re all steering the ship,” Dal Bon says. “Literally. Because we’re the Mariners.”

* * *

It’s a Saturday afternoon in Homer, and the Soldotna Stars are in town for this year’s homecoming game. The Mariners haven’t lost a league game to this point, beating Seward High School by 40 points in the season opener and Nikiski by 43 two weeks later to take a commanding lead in the Peninsula Conference.

But Soldotna has gone 81-2 over the past nine years, and given they’re one of the biggest schools in the state they shouldn’t even be playing Homer given the vast difference in student population (Homer is in a much smaller division). Alas, finding games in Alaska can be difficult, and sometimes involves 10-hour bus rides through the Denali Mountains to play North Pole High School (that’s a real school), ferry rides across icy waters to the nearby island of Kodiak or prop plane rides. So, it’s not strange that this is the second time that Soldotna, only a modest 90-minute drive up the Cook Inlet, appears as an opponent this season.

Soldotna won by 36 in the teams’ previous matchup, which was actually taken as a sign of progress for Homer. The Stars have a full-time weight training regimen. They have a ton of kids who are bigger and faster.

Dal Bon logs onto his laptop wearing a black T-shirt. In the background is a white painted stone fireplace and some logs, an end table and the corner of his couch. He’s looking out through an iPad pointed at midfield, with a scenic view of the Gulf just a few miles in the background.

“Can you zoom in, Harmony, just a hair … LOVE IT,” Dal Bon says. For the next few hours, he will be in a near-constant running dialogue with both the manager moving the iPad around the press box and coaches he’s tasked with communicating with about the upcoming defensive calls while holding an iPhone on speaker up to his chin. He is, it seems, the defensive coordinator’s defensive coordinator. A chief of staff who is there to ask what the call is going to be, suggest alternatives and offer running observations.

“Man, the internet connection is so 1995 right now,” he says as grainy shots of the field putter by like slow-loading slideshow images. At this point, Homer trails by two scores. “Giant lag. I missed what happened, Coach, do we still have the ball?

“Did they score there? Well, I’m glad I didn’t see it then.”

Depending on one’s perspective, there’s a uniquely modern beauty to it, people frantically navigating the annoyances and pitfalls of impersonal technology together for a common good. There’s also the universal solution to all problems beyond our expertise.

“Hey, Harmony? I’m gonna jump out and jump back in, see if that helps the connection,” he says, closing out Zoom to reveal a Chrome browser with about 15 other tabs open. “Hey, uh, I told Harmony I was jumping out but I don’t know if she heard me. Can you ask her to let me back in? What down is it?”

This is not the best afternoon for the Mariners, who end up losing 61-14, but the team was obviously getting better. Zank says that Dal Bon and Jessen added immeasurable benefits to the program. Dal Bon was a voice to lean on after games and practices and made a “huge difference” in the defensive game-planning process. Jessen was a Zen master on the sidelines keeping his players—and fellow in-person coaches—light and free of tension.

Tennison says Dal Bon “knows certain things about certain offenses that we just couldn’t see before. I could see our outside linebackers develop in ways we haven’t before.” In the first Soldotna game—again, the equivalent of Division III Huntingdon College taking on Alabama—he said they didn’t feel overmatched. They were down only 14-6 at the break and “the outside linebackers didn’t let anything outside of us.”

* * *

Homer clinched a first-round bye in the playoffs and was slated to face the winner of Redington High School and Valdez High School on Oct. 17 when two members of the team tested positive for COVID-19. The Mariners found out about the test result 15 minutes before practice and immediately went into a full shutdown, creating Zoom meetings for the coaches and players and virtual workouts away from school. Zank said in many ways they felt prepared since they worked “ahead of the curve” with technology all season. Their district agreed to postpone the game for two days, allowing the Mariners to compete following a full 14-day quarantine.

Then, on Tuesday, the Alaska School Activities Association abruptly canceled all playoffs for fall sports, ending the Mariners’ season altogether due to the pandemic. Zank struggled to come up with a message for the team. In his heart, he felt this was one of Homer’s best chances of winning the school’s first-ever state championship.

Those developments complicated an in-person visit to Alaska for Dal Bon, which he was planning for the better part of the season. He started a GoFundMe for flight and lodging money that made the rounds through high school coaching Twitter and earned Dal Bon a slice of celebrity.

Maybe, he says, he’ll write a book about it one day. He said he feels a bond with the players, which Tennison agrees is real.

When asked whether he grasps the magnitude of what happened, Dal Bon says he’s heard from other coaches during the pandemic who felt lost when there was no football taking place; they were envious of his new hobby. Almost subconsciously, he’d figured out a way to take the edge off the creeping loneliness, boredom and monotony that has vice-gripped most of the country. He’s inspired other coaches, quite possibly paving the way for more virtual work down the line should the public health emergency continue.

He managed to become part of something fulfilling. And, amid the virtual pandemic, something real.

“It’s weirdly normal,” he says of the experience. “The new normal. Me strangely yelling at my computer screen.”