After an up-and-down (mostly down) six seasons, the journeyman cornerback has found his way.

“Terrible. F---ing terrible, man.”

It’s a muggy late-July morning in Miami, on a sundrenched turf field framed by swaying palm trees. Not five minutes ago, sweaty and shirtless from a sprint workout that left his training partner retching over a nearby trash can, Eli Apple tossed me a football to help him “get some catches in” before an interview. A few fluttery passes later, however, the Bengals cornerback abruptly shakes his head in disgust and huffs toward the sidelines, ending our impromptu throwing session.

That’s when he starts telling me that he thinks I effing stink.

“So you don’t see me coming for Burrow’s job, then?” I ask.

“Brandon Allen got your ass beat,” Apple spits back, name-dropping Cincinnati’s backup quarterback. Then, to stress how low on the depth chart I’d fall, “and [running back] Joe Mixon.”

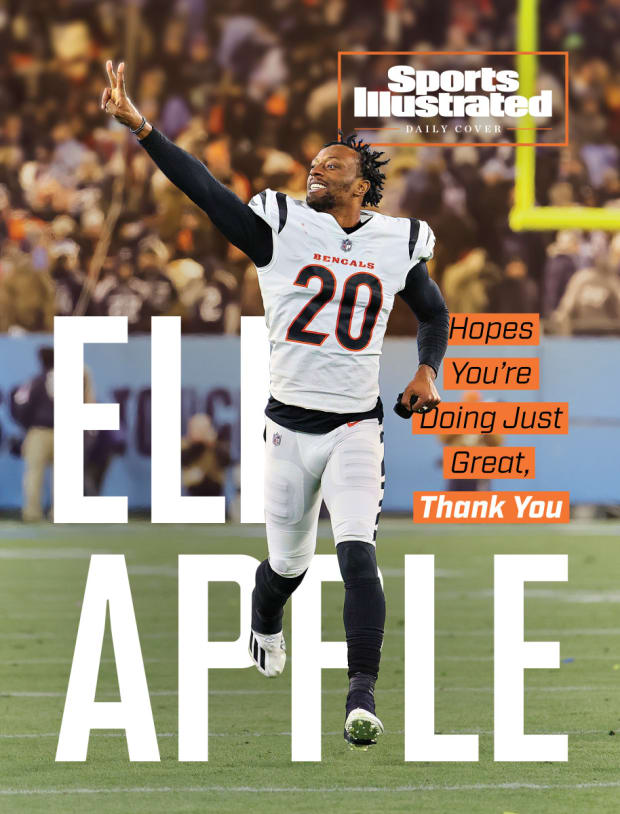

Andy Lyons/Getty Images

A beat passes as Apple plunks down on a metal bench, letting the burn sink in. Then at last he breaks, smirking as his tone softens. “I’m just talking s---,” he says.

Shocker, right? After all, the 27-year-old’s taste for smack talk is why I’m here in the first place. Most famously, this reputation is burnished on his 111,700-follower Twitter account, where an increasingly emboldened Apple burned every bridge in sight during the Bengals’ run to Super Bowl LVI last season. Included on the hit list were vanquished playoff foes like the Titans’ Julio Jones (“season on the line that man was hiding”) and the Chiefs’ Tyreek Hill (“He’s a baby ! @cheetah”), along with the entire residential population of one of Apple’s three previous NFL stops: “New Orleans is the dirtiest smelliest city and has the worst food ever 😂 it’s that swine and crawfish thts killin yall brains”.

But Apple walks the troll’s walk in real life, too. Listed at 6' 1" with a nearly 6' 4 1/2" wingspan, Apple has the size to physically harass receivers. He also has a willingness to verbally harangue them with his big mouth. (“I like to talk in general,” Apple says.) Together these traits have been known to rattle opponents and teammates alike: As star Bengals wideout Ja’Marr Chase told reporters during training camp, “He pisses me off, yeah, I ain’t gonna lie.”

This explains the scrumptious schadenfreude that was served up in February when Cooper Kupp snared the Super Bowl–winning touchdown over Apple with 1:25 left, sending the Rams to a 23–20 victory—and seemingly everyone else to their social media accounts. “Half the receivers in the NFL have chosen violence,” read one headline, recounting how players from the Chiefs, Ravens, Saints and others piled on with potshots, crying-face emojis, and reposts of a viral diss track: You never was a superstar/You must be on them [Xanax] bars/Cuz you acting like a fool…

It also explains the corner of YouTube dedicated to Apple’s lowlights, where popular recent uploads include “Eli Apple Getting Burned Compilation” (160,000 views); “Eli Apple getting burned compilation” (52,000); and “Scoring on Eli Apple with the WORST Receiver in EVERY Madden” (94,000). Then there were the many handwritten anti-Apple signs that popped up at Mardi Gras in March, such as the one held by a standing partygoer at a New Orleans intersection: “This corner is better than Eli Apple.”

The reality is that Apple enjoyed the best campaign of his pro career in 2021, leading NFL defensive backs in allowing a paltry 22.6 passer’s rating in man coverage, according to Pro Football Focus, and coming up with pivotal defensive plays in consecutive postseason wins. “He did a lot to get us where we were,” Bengals defensive coordinator Lou Anarumo says. But success alone hardly explains the outsized amount of attention for a former top-10 pick turned journeyman now on his fourth straight one-year contract.

“If Eli does something wrong—gives up a catch or whatever—next thing you know he’s trending on Twitter and everyone’s coming at him,” says Donte’ Deayon, a friend and fellow defensive back who got to know Apple when they were both rookies with the Giants in 2016. “Not everyone has to deal with that mentally.”

Not that Apple cares. Yes, he sees the memes. Yes, he saves the tweets. “I tell myself not to, like, ‘Aight, this the last time I’ma look at this s---,’ and then I still look at it again,” he says. But where his younger self might’ve endlessly stewed over every little slight, letting the emotion affect his job performance, today’s version claims to be “immune” to the hate that accompanies his heel status.

As he explains, “It ain’t about getting back at those people, proving anybody wrong. I don’t care about their opinion. I'm content as a football player. I’m gonna continue to work … [but] going from everything I went through to get to this moment, I feel like I’ve already reached that mountain peak.”

While this year’s tweetstorms ignited new levels of brouhaha, the cornerback was already accustomed to being a lightning rod. Look no further than what he faced in the leadup to the 2016 draft, after a sophomore season at Ohio State during which he won a College Football Playoff championship, made second-team All–Big Ten, and was named the Buckeyes’ defensive MVP: Granted anonymity by the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, one NFL scout blasted Apple, then 20, as not being first-round material because, as the scout put it, “[h]e has no life skills. At all. Can’t cook. Just a baby.”

The Giants’ controversial decision to take Apple at No. 10—second among cornerbacks behind Jalen Ramsey—did little to quell the stir. Neither did a social media video posted by Apple’s mother, Annie, of Eli buckled in the backseat, getting dropped off for his first day of minicamp practice that June. “People were making a big deal of that,” says Deayon, who recalls his new teammate likewise raising eyebrows with his reluctance to sing a song as part of a rookie ritual. “Everyone got rowdy and booed.”

Spending time with Apple, Deayon saw up close how the attention, amplified by the Big Apple–sized expectations, affected him: “You could see it weighing on him. Outside [work], he got a little more joy, he’s a little more focused, he’s studying the playbook, watching film. But then we got in the building and his attitude would change, because of all the outside factors that were coming at him.” The tension finally boiled over near the end of Apple’s second season in 2017, with Giants safety Landon Collins publicly labeling Apple as a locker room “cancer” and the team suspending Apple for its season finale over what it deemed “a pattern of behavior that is conduct detrimental …”.

Looking back, Apple uses simpler phrasing to describe what he felt at the time. “Shoot, basically hell, the worst part of being a football player, people criticizing me from every angle.” But he also takes ownership of the way he responded, chalking his suspension with the Giants up to his “lashing out, getting out of character,” and summarizing this whole period as the “low” of his career. Asked what he learned from it, Apple lists the importance of “appreciating every moment, not carrying stuff from off the field onto it, and being a better professional.”

More “humbling” moments awaited. The Giants traded him to New Orleans for fourth- and seventh-round picks in October 2018, the Saints subsequently declined his fifth-year player option in May ’19, and an injury-marred stint with the Panthers ended after less than five months in late October ’20. “I reinjured my hamstring I was dealing with throughout the whole year,” Apple says. “Then coach [Matt] Rhule tried to force me to practice [entering a Thursday night game against the Falcons in Week 8] when I was hurt. And I told him I couldn’t, and they cut me.” (A Panthers spokesperson, via email, responded: “Player health and safety is a priority for our organization. We categorically deny Eli’s allegation that we attempted to force him to practice when he was hurt. His release from the team was not due to injury.”)

Flying out to Los Angeles to live with his mom for the rest of the season, Apple entered a self-described period of soul-searching. “Reevaluating a lot of things, just trying to get my life right,” he says. And while he insists that he didn’t allow himself to wonder if his time in the NFL was running short, it took until the calendar flipped to 2021 before the phone rang with a familiar voice offering salvation. “Coach Lou was the only dude that trusted me,” Apple says. “He was able to give me an opportunity.”

Kareem Elgazzar/USA Today Network

As the Giants’ defensive backs coach during Apple’s last season there, Anarumo remembers working with a “feisty” corner who would cut the line to face Odell Beckham Jr. in one-on-one drills and “didn’t back down one ounce.” Like Apple, Anarumo acknowledges that the cornerback “had some growing up to do.” But it didn’t take much convincing of his Bengals colleagues to take a low-risk flier on Apple in March ’21, signing him to a $1.2 million, one-year, show-me deal.

“Anytime you struggle in this league at all, it instantly puts doubt in people’s minds,” Anarumo says. “[But] I just knew that we could get something out of him. There’s not a lot of humans walking around as big and strong and fast as he is, playing that position. I always thought, Keep giving him a chance.”

Anarumo was far from the only supportive voice in Cincinnati’s defensive room, with former teammates Vonn Bell (Ohio State) and Trey Hendrickson (New Orleans) among those providing a sense of familiarity and comfort that Apple lacked at his previous stops. “We got great leadership, so when I got there, I was able to share some of my experiences,” Apple says. “Those core people helped me a lot.” In turn the Bengals’ faith was rewarded when Apple, despite missing most of the preseason with an injury, earned the other starting cornerback spot opposite Chidobe Awuzie—another teammate whom Apple says he “really talked with” and grew close to—entering the Bengals’ opener. But it wasn’t until he snagged back-to-back interceptions against the Raiders and Steelers in Weeks 11 and 12 that his confidence truly took flight.

“I ended the season playing really well, so I was like, ‘You know what, s---, nobody can touch me, for real,’” Apple recalls, grinning at the memory. “Then I hit the playoffs with that same attitude.”

And how did that feel?

“It felt amazing, man. That's kind of probably why I was going off a little bit on Twitter and everything—feeling that power, feeling that invincibility.”

Slamming his helmet in his stall, Apple sat in the visiting locker room at Arrowhead Stadium and fumed. It was halftime of the AFC title game in late January and the Bengals were behind 21–10, a sizable enough deficit to make Apple forget the touchdown-saving goal-line tackle that he had just made on Tyreek Hill as the second quarter ended. “I was so frustrated, I just threw him on the ground and looked down,” Apple says. “I didn’t have a chance to really appreciate how big that play was until after.”

One week earlier, Apple had helped clinch Cincinnati’s divisional round win over the Titans in equally heroic fashion, deflecting a Ryan Tannehill pass with 20 seconds left in a tied game that led to an interception the key play in setting up Evan McPherson’s walk-off field goal. And so, when the Bengals outlasted the Chiefs as well, eliminating the defending champions in overtime, Apple didn’t hold back, tweeting at Kansas City’s Mecole Hardman and Hill to “dm me yall number and I'll hook y’all up wit them super bowl tickets on me”.

Paul Sancya/AP/Shutterstock

To veteran safety Mike Thomas, who like Anarumo briefly crossed paths with Apple on the Giants in 2018 before reuniting in Cincinnati last season, these social media screeds were born out of a sense of “redemption, because Eli’s tape showed that he’s an elite corner.” Adds Thomas, “Anytime you attract that type of attention and you pop off on social media, you might get some attention that you’re not looking for. But that’s his personality. He’s high-energy. He’s physical. He wants that pressure.”

Not that many others bothered to give Apple the benefit of the doubt after Kupp, the Super Bowl MVP, beat him on a fade route to the back-right corner of the end zone. “It’s very cosmic comeuppance, isn’t it?” says Uday Toodi, a 27-year-old lifelong Louisiana resident and Saints fan. Searching for a spot near New Orleans City Park to post up for the Mardi Gras parade in March, Toodi and his friends came across a house displaying a banner that read, “Eli Apple eats Walmart king cakes”. Striking up a conversation with its creator, Toodi found common ground in a shared enemy. “With [Apple], it’s definitely personal,” Toodi says.

The same, however, cannot be said for Apple in the wake of his most public failure. Flipping on the film “right after the game,” Apple confirmed what went wrong against Kupp—“my leverage, I was too far inside. Could have been more head-up, understanding-the-situation, what-they-were-gonna-do-type s---.”—and blocked out the rest. Asked if he was caught off guard by the torrent of gleefully mocking messages from fans that followed, he replies, “Man, those people don’t matter to me at all. But it made it more interesting.”

And what about Hill, Hardman or other peers in the league?

“S---, they didn’t beat me, so I don’t care.”

An hour and a half or so before Apple spit-roasted my throwing arm, I first met him at 5:15 a.m. at the gym of a private high school near Miami International Airport, plane lights twinkling overhead. With his trainer running late, Apple took charge and led a friend—former Giants teammate and area native Jeremiah McKinnon—through an intense abdominal, chest and arm circuit that he had committed to memory, calling out each drill in advance. This was impressive enough. Then Apple casually revealed how much sleep he and McKinnon had gotten the previous night too.

“None.”

“Where’d you come from?” I ask.

“Right from the crib. We had a nice little dinner, then went to the crib, and I just stayed up.”

Later, Apple admits rest is one area where he has plenty of room to grow. “I don’t get too many hours, so that’s something I’m still fighting,” he says, adding that he has downloaded various meditation and sleep apps to help promote stronger shuteye. Otherwise, though, Apple feels that he has reached the mountain peak when it comes to taking care of himself. He does yoga regularly, recovers with a weekly acupuncture session and engages his mind by reading a wide range of books (“I’m on The Alchemist right now, but really anything I can get my hands on”). If that anonymous NFL scout ever wanted to truly test Apple’s cooking acumen, the fully vegan cornerback—he cut out animal products two years ago—could serve up his special jackfruit-and-bean enchiladas.

Anarumo similarly observes a heightened diligence in Apple’s preparation at the Bengals’ facility. “He’s always been a good worker, but I think he’s working better now, more with a purpose,” Anarumo says, specifically pointing to “the way he asks questions in meetings.” But this evolution has also coincided with the emergence of the more playful side of Apple’s persona that Anarumo hardly knew from their time in New York together. “He’s always got guys in his corner of the locker room,” Anarumo says. “I don't know what they’re laughing about, but he’s got them going, keeping things light.”

For Apple, who in March reupped with Cincinnati on a one-year, $3.75 million deal that Taylor declared a “no-brainer” decision for the team, the source of this joy is simple. Asked what his teammates see in the way he goes about his business, Apple says, “They see somebody who’s free, who loves and appreciates every moment. Somebody that understands that game was almost taken from [him].”

So he dances in drill lines at practice, getting down to Davido and other favorite Afrobeat artists but also really “any song that’s got a good beat.” At the same time he siphons energy from teammates like defensive tackle D.J. Reader, whose signature “gravedigger” celebration encouraged Apple to revel in less analogue ways last season as Cincinnati captured its first AFC North title since 2015.

If Reader is the gravedigger, does that make you the keyboard warrior?

“Yeah, man, I’m the gravedigger on the keyboard!” he chuckles.

While Apple pulls no punches on Twitter, though, he professes to follow something of a chatterbox’s code with opponents. “I don’t like to go out there and just deliberately try to get in somebody’s head,” he says. “I like to check in on guys, just have free conversation: How you doing? What you eat today? Your body feeling good? I know what route you’re running here, just know that’s not gonna work. It ain’t like, ‘F--- you.’ I ain’t go right into that. And if they say something malicious, we can get to that.” Of course, he adds, “I know it’s only as valuable as somebody that makes plays. That’s all that matters.”

When it comes to the most prolific gabbers on the other side of the ball, Apple describes divisional rivals in the Ravens’ Rashad Bateman and the Steelers’ Chase Claypool as “big talkers,” along with one of the Kansas City wideouts who later trashed him on Twitter: “I remember Hardman, he was talking a lot, fa sho.” Perhaps earlier in his career Apple would’ve let these interactions fester and affect his play. “It can have you up all night, it can have you losing sleep for no reason, worrying about what other people got to say about you,” he says. Entering his seventh season, however, “I’m at a place where it ain’t even about that. Just do your job and all that s--- [is] gonna take care of itself.”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

A younger Apple likely would’ve struggled with the reaction to Kupp’s grab, from the immediate public shaming that he received on social media to the countless times that the replay has flashed across his television screen: “You see it everywhere, man.” And later, responding to a question about who he considers the toughest receivers to cover—“Davante Adams … Tyreek Hill … of course Ja’Marr [and teammate] Tee Higgins…”—Apple cracks a wide smile as he gets to the man who burned him best. “Cooper Kupp’s a beast. Everybody knows that.”

Even on yet another one-year contract, he’s found a level of stability and serenity he’s never had since entering the NFL. “Not For Long, that’s what it stands for,” Apple says. “I have a lot of friends that I’ve played with [who are] out of the league. So I play for them, continue to live my life freely.” And in the calm before his seventh season begins, as our chat comes to a close, this attitude comes through when I ask Apple whether he has any rival fan bases currently fixed in his crosshairs, or any parting shots for Bengals opponents.

“Nah, I don’t got no shots to take,” he replies. “Hope everybody doing great, loving life and everything. I ain’t got nothing for nobody.”

How about: See you on Twitter?

“Yeah, yeah, I’ll see ‘em on Twitter, though. Fa sho.”

• Joe Burrow and Cincinnati’s New Normal

• Gabriel Taylor Is the Late Sean Taylor’s Brother—and Maybe His Successor

• Predicting All 272 Games of the NFL Season

• She Kicked for Vanderbilt, and Then Things Got Hard